Of Undergraduate Research in Communications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. in Re

Electronically Filed Docket: 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD (2010-2013) Filing Date: 12/29/2017 03:37:55 PM EST Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF THE MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS 2010-2013 CABLE ROYALTY YEARS VOLUME I OF II WRITTEN TESTIMONY AND EXHIBITS Gregory O. Olaniran D.C. Bar No. 455784 Lucy Holmes Plovnick D.C. Bar No. 488752 Alesha M. Dominique D.C. Bar No. 990311 Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP 1818 N Street NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20036 (202) 355-7917 (Telephone) (202) 355-7887 (Facsimile) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for MPAA-Represented Program Suppliers December 29, 2017 Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS FOR 2010-2013 CABLE ROYALTY YEARS The Motion Picture Association of America, Inc. (“MPAA”), its member companies and other producers and/or distributors of syndicated series, movies, specials, and non-team sports broadcast by television stations who have agreed to representation by MPAA (“MPAA-represented Program Suppliers”),1 in accordance with the procedural schedule set forth in Appendix A to the December 22, 2017 Order Consolidating Proceedings And Reinstating Case Schedule issued by the Copyright Royalty Judges (“Judges”), hereby submit their Written Direct Statement Regarding Distribution Methodologies (“WDS-D”) for the 2010-2013 cable royalty years2 in the consolidated 1 Lists of MPAA-represented Program Suppliers for each of the cable royalty years at issue in this consolidated proceeding are included as Appendix A to the Written Direct Testimony of Jane Saunders. -

TV Shows Tried

TV Shows Tried. by SciFiOne (scifione.net) Show Name Watch Ln Yr Tried Review / Comments Final results Call Me Kat No 0.5 2021 I was almost instantly bored and did not get far. Abandoned Call Your Mother unlikely 0.5 2021 A no laughs pilot for a sitcom about an empty nest mom who can't let go flying to LA to be with her semi-functional kids. I'll try one more. L.A.'s Finest No 1.0 2021 A much too gritty and graphic cop / crime drama.. Abandoned Mr Mayor No 0.5 2021 This sitcom pilot was too stupid and acrimonious. I did not get far. Abandoned New Tricks OK 1.0 2021 A slightly humorous 2004 UK police procedural. A team of retired old school Disposable male cops lead by a not so young female detective investigates old crimes. The personal life bits are weak but the detective interactions are good. Queen's Gambit OK 1.0 2021 A 7 part miniseries on Netflix about a young damaged and addicted character Disposable who just happens to be a chess prodigy too. It's about 33% too long. Resident Alien No 1.0 2021 Two votes. One= nothing was happening. Two= it was dumb. We gave up less Abandoned than half way. Later I finished it & it was OK at 120% speed= not worth it. Shetland No 1.0 202 Slow, dour, dark. and nasty police murder investigation series in the Shetlands. Abandoned Well done, but way to unlikable to watch. Vera No 1.5 2021 A well done police murder detective show but too long, slow, and depressing Abandoned (even the irascible protagonist). -

Marching for Healthy Babies

WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY, APRIL 13 & SATURDAY, APRIL 14, 2012 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Hair- raising efforts Loveloud A Wellborn-based United Way’s alternative rock/group, local impact Loveloud is the final per- formance in this season’s totals $1,075,973. FGC Entertainment series. The group, most recently By TONY BRITT seen on the Warped Tour, [email protected] perform on April 14th at Florida Gateway College. For more information or Few, if any men, want to for tickets, call (386) 754- lose most of their hair at 4340 or visit www.fgcenter- one time. tainment.com. But if losing his hair, in a public meeting, with a Toxic roundup pair of pink hair clippers, in front of close to 100 people The Columbia County meant the United Way of Toxic Roundup will be Suwannee Valley met its Saturday, April 14 at challenge goal, then Mike the Columbia County McKee, United Way presi- Fairgrounds from 9 a.m. dent took the buzz cut as a to 3 p.m. Safely dispose of COURTESY PHOTO good sport. your household hazard- Kaylie Spradley at 8 and a half months old in a photo taken Jan. 12. United Way of Suwannee ous wastes, including old Valley held its 2012 Royal paint, used oil, pesticides Awards Banquet and annual and insecticides. The meeting Thursday night at process is quick, easy Florida Gateway College and free of charge to Howard Conference Center, residents. There is a small Marching for chronicling the organiza- fee for businesses. Help keep our environment HAIR continued on 7A safe! For information call Columbia County landfill Healthy Babies at (386)752-6050. -

TV1-SF-SET Australia Opportunity Overview

TV1-SF-SET Australia Opportunity Overview May 2013 [PRELIMINARY DRAFT] Executive Summary Sony Pictures Television (“SPT”) is seeking approval to take ownership control of the TV1 and Sci-Fi (SF) channels and utilize the TV1/SF infrastructure and management team to launch a 3rd Sony branded (“SET”) channel in Australia on the Foxtel platform • SPT, CBS Studios, and Comcast/NBC Universal are currently equal partners in Australian Pay-TV channels TV1 and Sci-Fi (SF) on the Foxtel platform • Recent affiliate renewal negotiations has Foxtel significantly reducing subscriber fees for both TV1 and SF which have historically contributed ~50% to total revenue • The fee reductions have forced the board/management to consider (1) dissolving the partnership or (2) reducing programming and operating costs to off-set the expected decline in subscription revenue • SPT is proposing a 3rd option which would have SPT take on the TV1 and SF channels, streamline their operations and utilize their infrastructure/team to launch a 3rd channel branded “SET” • SPT’s proposed SET channel would consist of TV and film product from various genres, leveraging Sony’s extensive content library • New SET channel to be created in parallel to running TV1 and SF and assumes a Jan 1, 2014 launch date • The current consolidated business plan has projected NPV of $14.7M and a DWM of ($5.2M). NPV of $17.8M and a DWM of ($3.3M) when including incremental license fees paid to SPE (1) (1) Incremental license fees assumes 75% of SET channel content will be SPE library content. Includes 15% for residuals and 40% in2 taxes. -

Baffert's Bodemeister Works out Isn't He Clever out of Contention

B4 Friday, April 27, 2012 | TV/SPORTS | www.kentuckynewera.com FRIDAY PRIMETIME APRIL 27, 2012 N - NEW WAVE M - MEDIACOM S1 - DISH NETWORK S2 - DIRECTV N M 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 1:30 S1 S2 :35 :05 :35 :35 (2) (2) WKRN [2] Nashville's Nashville's Nashville's ABC World Nashville's Wheel of Shark Tank Primetime: What 20/20 Nashville's News Jimmy Kimmel Live Extra Law & Order: C.I. Paid ABC News 2 News 2 News 2 News News 2 Fortune Would You Do? News 2 "Ten Count" Program 2 2 :35 :35 :35 :05 (4) WSMV [4] Channel 4 Channel 4 Channel 4 NBC News Channel 4 Channel 4 Think You Are "Rob Grimm "Leave It to Dateline NBC Channel 4 J. Leno Mel Gibson, LateNight Fallon Carson Today Show NBC News News News 5 News Lowe" (N) Beavers" (N) News The Wanted (N) Matthew Broderick Daly 4 4 :35 :35 :35 :05 (5) (5) WTVF [5] News 5 Inside News 5 CBSNews News Channel 5 Under Boss "Philly CSI: NY "Slainte" (N) Blue Bloods "Working News 5 David Letterman The Late, Late Frasier Law & Order CBS Edition Pretzel Company" (N) Girls" (N) Show "Computer Virus" 5 5 :35 :35 :35 :05 (6) (6) WPSD Dr. Phil Local 6 at NBC News Local 6 at Wheel of Think You Are "Rob Grimm "Leave It to Dateline NBC Local 6 at J. -

Alessandro Quarta Cv Formazione

ALESSANDRO QUARTA CV Doppiatore, Direttore di doppiaggio, Adattatore dialoghista, Attore, Cantante, Compositore. Alessandro Quarta è uno dei massimi esponenti del doppiaggio italiano, è attore teatrale da quando aveva 6 anni, 1976, e Doppiatore dal 1980. In 40 anni di carriera a doppiato più di 1200 opere, tra film, serie TV e film di animazione, tra cui Casey Affleck, Ethan Hawke, Jeremy Renner, Paul Rudd, Ed Helms, Mark Wahlberg, Peter Sarsgaard e ha vinto numerosi premi come miglior voce maschile. È la voce ufficiale italiana di Mickey Mouse dal 1995, è il doppiatore che l’ha interpretato da più tempo in Italia e, per questo, è il primo ad aver ricevuto un riconoscimento ufficiale direttamente da Disney Company, il “Premio Speciale Mickey 90”. L’Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Los Angeles gli ha conferito il primo riconoscimento a un doppiatore italiano negli USA, il “IIC Los Angeles Creativity Award”, come ambasciatore della lingua italiana nel mondo. Come rappresentante del doppiaggio italiano, ha partecipato al tour di presentazione negli USA del libro “Senti chi parla! Le 101 frasi più famose del cinema”, tenendo interventi presso la Chapman University di Orange County, in California, l’Università di Houston, e presso l’Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Los Angeles. Ricopre anche il ruolo di Direttore di doppiaggio e Adattatore Dialoghista di film cinema, serie TV e Cartoni Animati. Insegna doppiaggio e recitazione presso accademie e scuole di recitazione e doppiaggio, e ha tenuto corsi di doppiaggio presso l’Università degli studi di Salerno. Partecipa al Cortometraggio AttorInVoce alla 74ª Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica la Biennale di Venezia e alla mostra fotografica “AttorInVoce” presso la Casa del Cinema di Roma, nei quali è stato scelto assieme ai migliori doppiatori italiani. -

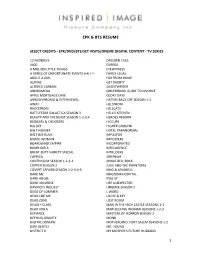

Epk & Bts Resume 1 Select Credits

EPK & BTS RESUME SELECT CREDITS - EPK/DVD/BTS/SET VISITS/ONLINE DIGITAL CONTENT - TV SERIES 12 MONKEYS DRESDEN FILES 4400 EUREKA A MILLION LITTLE THINGS EYEWITNESS A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS SSN 1-2 FAIRLY LEGAL ABOUT A GIRL FAR FROM HOME ALPHAS GET SHORTY ALTERED CARBON GHOSTWRITER ANDROMEDA GIRLFRIENDS’ GUIDE TO DIVORCE APPLE MORTGAGE CAKE GLORY DAYS ARROW (PROMO & INTERVIEWS) HATERS BACK OFF SEASON 1-2 AWAY HELSTROM BACKSTROM HELLCATS BATTLESTAR GALACTICA SEASON 3 HELL’S KITCHEN BEAUTY AND THE BEAST SEASON 1-2-3-4 HEROES REBORN BEGGARS & CHOOSERS HICCUPS BIG SKY HIGHER GROUND BIG THUNDER HOTEL PARANORMAL BIG TIME RUSH IMPASTOR BIONIC WOMAN IMPOSTERS BOARDWALK EMPIRE INCORPORATED BOMB GIRLS INTELLIGENCE BRENT BUTT VARIETY SPECIAL INTRUDERS CAPRICA JEREMIAH CONTINUUM SEASON 1-2-3-4 JINGLE BELL ROCK COPPER SEASON 2 JULIE AND THE PHANTOMS COVERT AFFAIRS SEASON 1-2-3-4-5 KING & MAXWELL DARE ME KINGDOM HOSPITAL DARK ANGEL KYLE XY DARK UNIVERSE LIFE UNEXPECTED DAVINCI’S INQUEST LINGERIE SEASON 2 DEAD OF SUMMER L WORD DEAD LIKE ME LOCKE & KEY DEAD ZONE LOST ROOM DEADLY CLASS MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE SEASONS 1-2 DEAR VIOLA MAN SEEKING WOMAN SEASONS 1-2-3 DEFIANCE MASTERS OF HORROR SEASON 2 DEFYING GRAVITY MONK DIGITAL DOMAIN MOTHERLAND: FORT SALEM SEASONS 1-2 DIRK GENTLY MR. YOUNG DISTRICT 9 MY MOTHER’S FUTURE HUSBAND 1 EPK & BTS RESUME MYSTERIOUS WAYS SUPERNATURAL ONCE UPON A TIME SWEET SOUL BURLESQUE ORPHAN BLACK (Promo) SYFY UK FLASH GORDON OUTER LIMITS TALKING TO HOLLYWOOD PLAYGROUND THE 100 SEASON 1-2-3-4-5-6 PRIMEVAL THE ART OF MORE -

The Upside of Anger, Mr. Holland's Opus, Four Rooms

‘THE MISTLETOE INN’ Cast Bios ALICIA WITT (Kim Rossi) – Starting with her debut in 1984 at the mere age of seven as Alia in David Lynch’s science fiction classic, Dune, Alicia Witt has garnered nearly a three-decade long career as an actor and singer-songwriter. Witt recently received rave reviews for her role as Paula in AMC’s critically acclaimed series “The Walking Dead.” Witt is currently appearing and singing on ABC’s hit drama series “Nashville” as country star Autumn Chase, and seen on cult favorites “Supernatural” (CW) and returning to David Lynch’s long anticipated “Twin Peaks” on Showtime, reprising her role from the original series. In 2016, Witt starred in Hallmark Channel’s original movie “The Christmas List.” In 2014, Witt joined the cast of the Emmy® Award-winning FX series “Justified” as Wendy Crowe, the smart and sexy paralegal sister of crime lord Danny Crowe. She made a provocative addition to this critically acclaimed series. Off screen a classically trained pianist and phenomenal singer, Witt is one of those rare talents whose passion as a singer-songwriter is also gaining tremendous attention from both the industry and her fans. Alicia is currently in the studio recording her newest album, 15,000 Days, with Grammy® Award-winning producer Jacquire King (Kings of Leon, Norah Jones, Ingrid Michaelson, Tom Waits, James Bay). She recently made her debut at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville and has also performed live as a musical guest on CBS’s “Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson” and “The Queen Latifah Show.” Witt released her first full-length studio album, Revisionary History, in May 2015, which has garnered comparisons to Elton John, Fiona Apple and Carole King. -

Episode Guide

Episode Guide Episodes 001–023 Last episode aired Friday June 15, 2012 www.usanetwork.com c c 2012 www.tv.com c 2012 c 2012 www.tvrage.com www.usanetwork.com The summaries and recaps of all the Fairly Legal episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http://www. usanetwork.com and http://www.tvrage.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on June 28, 2017 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.59 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 Priceless . .7 3 Benched . 11 4 Bo Me Once . 13 5 The Two Richards . 17 6 Believers . 19 7 Coming Home . 21 8 Ultravinyl . 25 9 My Best Friend’s Prenup . 29 10 Bridges . 31 Season 2 35 1 Satisfaction . 37 2 Start Me Up . 41 3 Bait and Switch . 45 4 Shine a Light . 49 5 Gimme Shelter . 53 6 What They Seem . 55 7 Teenage Wasteland . 59 8 Ripple of Hope . 63 9 Kiss Me, Kate . 67 10 Shattered . 69 11 Borderline . 71 12 Force Majeure . 73 13 Finale . 75 Actor Appearances 77 Fairly Legal Episode Guide II Season One Fairly Legal Episode Guide Pilot Season 1 Episode Number: 1 Season Episode: 1 Originally aired: Thursday January 20, 2011 Writer: Michael Sardo Director: Bronwen Hughes Show Stars: Baron Vaughn (Leonardo Prince), Virgina Williams (Lauren Reed), Michael Trucco (Justin Patrick), Sarah Shahi (Kate Reed) Guest Stars: Anthony Joseph (D’sean Henry), Alex Arsenault (Hoodie), Michael Adamthwaite (Cashier), Terence Kelly (Marty Fliegel), Maureen Thomas (Phyllis Fliegel), Ty Olsson (Sergeant Danny Harrington), Dan Jof- fre (Deli Owner), Elfina Luk (Waitress), Elizabeth Weinstein (Secre- tary #1), Lissa Neptuno (Secretary #2), Marci T. -

Papa John's Back in Business

WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY, APRIL 6 & SATURDAY, APRIL 7, 2012 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Skunkie Acres called ‘nuisance’ Tractor & engine show The 24th annual Antique Commissioner Tractor and Engine Show Ron Williams: ‘The continues Friday and Saturday from 9 a.m. to 5 smell is awful.’ p.m. at the Stephen Foster Folk Culture Center State HANNAH O. BROWN Park in White Springs. [email protected] See working equipment and demonstrations from Commissioner Ron rural America’s history. Williams declared Skunkie There will be competitions Acres, a self-described for adults and children and exotic zoo and animal on Saturday an antique trac- rescue shelter in White tor parade. Admission is Springs, a “nuisance” at $5 per vehicle of up to six the county commission people. (See story on 5A.) meeting on Thursday. “The smell is awful,” Painting contest Williams said. Williams said that he The Art League of North JASON MATTHEW WALKER/Lake City Reporter had recieved continual Florida is sponsoring an art Clanton uses non-potable water to spray deposits and debris free from a clarifier, which can hold about 250,000 gallons complaints from neighbors contest (plein air) on April of water. of the shelter concerning 7 as part of the Alligator an unpleasant odor, horses Lake Festival. Check- tied to county roads, horse in is between 8:30 a.m. feces on roads around the and 11:30 a.m. at the Art facility and barking dogs. League booth. The judging Williams also said the and awards will be present- shelter was calling itself a ed shortly after noon. -

Epk & Bts Resume 1 Select Credits

EPK & BTS RESUME SELECT CREDITS - EPK/DVD/BTS/SET VISITS/ONLINE DIGITAL CONTENT - TV SERIES 12 MONKEYS FAR FROM HOME 4400 GIRLFRIENDS’ GUIDE TO DIVORCE A MILLION LITTLE THINGS GLORY DAYS A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS SSN 1-2 HATERS BACK OFF SEASON 1-2 ABOUT A GIRL HELLCATS ALPHAS HELL’S KITCHEN ANDROMEDA HEROES REBORN APPLE MORTGAGE CAKE HICCUPS ARROW (PROMO & INTERVIEWS) HIGHER GROUND BACKSTROM IMPASTOR BATTLESTAR GALACTICA SEASON 3 IMPOSTERS BEAUTY AND THE BEAST SEASON 1-2-3-4 INCORPORATED BEGGARS & CHOOSERS INTELLIGENCE BIG THUNDER INTRUDERS BIG TIME RUSH JEREMIAH BIONIC WOMAN JINGLE BELL ROCK BOARDWALK EMPIRE KING & MAXWELL BOMB GIRLS KINGDOM HOSPITAL BRENT BUTT VARIETY SPECIAL KYLE XY CAPRICA LIFE UNEXPECTED CONTINUUM SEASON 1-2-3-4 LINGERIE SEASON 2 COPPER SEASON 2 L WORD COVERT AFFAIRS SEASON 1-2-3-4-5 LOST ROOM DARE ME MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE SEASON 1-2 DARK ANGEL MAN SEEKING WOMAN SEASON 1-2-3 DARK UNIVERSE MASTERS OF HORROR SEASON 2 DAVINCI’S INQUEST MONK DEAD OF SUMMER MR. YOUNG DEAD LIKE ME MY MOTHER’S FUTURE HUSBAND DEAD ZONE MYSTERIOUS WAYS DEAR VIOLA ONCE UPON A TIME DEFIANCE ORPHAN BLACK (Promo) DEFYING GRAVITY OUTER LIMITS DIGITAL DOMAIN PLAYGROUND DIRK GENTLY PRIMEVAL DISTRICT 9 PRISON BREAK: SEQUEL DRESDEN FILES PRIVATE EYES EUREKA PSYCH EYEWITNESS PROJECT RUNWAY CANADA FAIRLY LEGAL PSYCH SEASON 5-6 1 EPK & BTS RESUME REAL HOUSEWIVES OF VANCOUVER TALKING TO HOLLYWOOD REIGN SEASON 1 THE 100 SEASON 1-2-3-4-5-6 RIESE THE ART OF MORE SEASON 2 RIVERDALE THE BOYS ROBSON ARMS THE EXPANSE SEASON 1-2-3 ROMEO THE FLASH (PROMO -

Spring 2011 (PDF)

SPRING 2011 Critical Thinking Tiger-style Disputes Without Drama Vampire Biology PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE CONTENTS PETS AND VETS Board of Trustees Peter D. Miller, Chair 4 Thought Processes Philip A. Wilheit Sr., Vice Chair Brenau’s new critical thinking initiative pairs James Anthony Walters, Secretary Carole Ann Carter Daniel, WC ’68, Treasurer with a new minor, philosophy, as part of a grand sually in this column I try to deal somewhat Gale Johnson Allen, EWC ’91 strategy to solve a serious problem in today’s Melissa A. Blanchard, A ‘88 colleges and universities. dispassionately with aspects of Brenau’s vision Raymond H. Burch or some issue affecting the academic world or Roger Dailey Robin Smith Dudley, WC ’78 society. Today, however, it is not business as usual; I call this photo of Jackson, Edward and Bogey ‘my three sons.’ Kathryn (Kit) Dunlap, WC ’64 Elizabeth (Beth) Fisher, WC ‘67 Uit’s personal. Pets of assorted species and description have John B. Floyd 6 Balancing Act always been part of my life, which would not have been as full understand that they are signing up to be animal doctors and M. Douglas Ivester Danita Emma taught students at Brenau while she was and rich without the love and friendship we shared. (Aside: human psychologists? I have nothing against human caregiv- John W. Jacobs Jr. their undergraduate classmate. Now the classically trained Angela B. Johnston, EWC ’95, ’06 dancer runs a highly acclaimed summer program at Syracuse Thinking about pets past and present for me is like listening to ers – my daughter is a physician and my son is a dentist.