Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deconstructing Windhoek: the Urban Morphology of a Post-Apartheid City

No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 Working Paper No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Contents PREFACE 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 2. WINDHOEK CONTEXTUALISED ....................................................................... 2 2.1 Colonising the City ......................................................................................... 3 2.2 The Apartheid Legacy in an Independent Windhoek ..................................... 7 2.2.1 "People There Don't Even Know What Poverty Is" .............................. 8 2.2.2 "They Have a Different Culture and Lifestyle" ...................................... 10 3. ON SEGREGATION AND EXCLUSION: A WINDHOEK PROBLEMATIC ........ 11 3.1 Re-Segregating Windhoek ............................................................................. 12 3.2 Race vs. Socio-Economics: Two Sides of the Segragation Coin ................... 13 3.3 Problematising De/Segregation ...................................................................... 16 3.3.1 Segregation and the Excluders ............................................................. 16 3.3.2 Segregation and the Excluded: Beyond Desegregation ....................... 17 4. SUBURBANISING WINDHOEK: TOWARDS GREATER INTEGRATION? ....... 19 4.1 The Municipality's -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

The Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Nurses Regarding the Provision of Services on Cervical Cancer at Healthcare Facilities in Windhoek District, Namibia

THE KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDE AND PRACTICES OF NURSES REGARDING THE PROVISION OF SERVICES ON CERVICAL CANCER AT HEALTHCARE FACILITIES IN WINDHOEK DISTRICT, NAMIBIA NDAHAFA A SHIWEDA NOVEMBER 2019 i THE KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDE AND PRACTICES OF NURSES REGARDING THE PROVISION OF SERVICES ON CERVICAL CANCER AT HEALTHCARE FACILITIES IN WINDHOEK DISTRICT, NAMIBIA A RESEARCH THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE MASTERS DEGREE OF NURSING SCIENCE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA BY NDAHAFA A SHIWEDA 201304589 NOVEMBER 2019 MAIN SUPERVISOR: DR HANS J AMUKUGO ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to determine the knowledge, attitudes and practices of nurses regarding the provision of services on cervical cancer at the health facilities in Windhoek district, Namibia. To achieve this aim, four objectives were set: (a) to assess the knowledge of cervical cancer and cervical cancer services among nurses (b) to determine the nurses' attitudes towards the provision of cervical cancer services (c) to assess the practices of nurses towards the provision of services on cervical cancer; and (d) to analyse the association between the key variables with regards to cervical cancer and the provision of its services. A quantitative, descriptive and analytical study, using a self-administered structured questionnaire was completed in 2019. Data on socio-demographic, knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding cervical cancer service provision was collected from nurses that are working at the randomly selected healthcare facilities such as Windhoek Central hospitals, Intermediate Katutura Hospital, Hakahana clinic, Wanaheda clinic, Okuryangava clinic and Katutura Health Centre. A total of eighty (80) participants was sampled with the means of stratified random sampling, proportionate to the size of the population at a certain health facility. -

A Comparative Study of Socio-Economic Status and Living

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS AND LIVING CONDITIONS AMONG RESIDENTS OF WANAHEDA FORMAL AND HAKAHANA INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA BY MALAKIA HAIMBODI 200504916 MARCH 2014 Supervisor: Prof. Piet van Rooyen (UNAM) External Examiner: Dr. Costa Hofisi (North-West University) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGMENT .................................................................................................................. iii DEDICATION .................................................................................................................................. v DECLARATION ............................................................................................................................. vi CHAPTER ONE: Orientation of the study .......................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Statement of the problem.........................................................................................................3 1.3 Research objectives .................................................................................................................3 1.4 Research questions -

The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia Katherine Caufield Arnold College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, Katherine Caufield, "The rT ansformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 251. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/251 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Introduction Although we kept the fire alive, I well remember somebody telling me once, “We have been waiting for the coming of our Lord. But He is not coming. So we will wait forever for the liberation of Namibia.” I told him, “For sure, the Lord will come, and Namibia will be free.” -Pastor Zephania Kameeta, 1989 On June 30, 1971, risking persecution and death, the African leaders of the two largest Lutheran churches in Namibia1 issued a scathing “Open Letter” to the Prime Minister of South Africa, condemning both South Africa’s illegal occupation of Namibia and its implementation of a vicious apartheid system. It was the first time a church in Namibia had come out publicly against the South African government, and after the publication of the “Open Letter,” Anglican and Roman Catholic churches in Namibia reacted with solidarity. -

Improving Communication Between the Residents of Katutura and the City of Windhoek

Enhancing Understanding of Utility Services: Improving communication between the residents of Katutura and the City of Windhoek Jo Bridge Brenden Brown Kyle Robichaud Ben Thistle Sponsored by: Desert Research Foundation of Namibia Enhancing Understanding of Utility Services: Improving communication between the residents of Katutura and the City of Windhoek An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelors of Science by Jo Bridge Brenden Brown Kyle Robichaud Ben Thistle Date: 5 May 2006 Report Submitted to: Dr. Mary Seely, Desert Research Foundation of Namibia Mrs. Anna Matros, Desert Research Foundation of Namibia Professor Chrysanthe Demetry, Worcester Polytechnic Institute Professor Richard Vaz, Worcester Polytechnic Institute Executive Summary Namibia was established as a free and independent country in 1990 after its release from the South African apartheid government; the nation has made significant progress with class integration since this time, but continues to face economic, environmental, and social problems. There continues to be a great disparity between rich and poor, and obstacles still exist between races. In both rural and urban regions of the country, many people live in shacks made from corrugated steel with little access to water, electricity, and basic sanitation. Since Independence, there has been a high number of rural citizens migrating to the capital city of Windhoek, most of whom end up living in shacks in the informal settlements of Katutura. This large influx in population, combined with a lack of job opportunities, has caused the unemployment rate in the Windhoek area to rise to around 30%. -

8D7N Best of Nambia

0 Windhoeekk –– SossusvleiSossusvlei –– Walvisalvis BayBay –– SwakopmundSwakopmund –– Windhoekk Namib Desert, Sossuslei MINIMUM 4 ADULTS Season Twin Share Single Room Supplement January - June 11,950 1,820 July – November 12,260 1,890 December 12,510 1,960 PRICE INCLUSIONS Return airport-hotel-airport transfer Day City Hotel/Lodge (or similar class) 07 Nights hotel accommodation with 01 Windhoek Avani Windhoek Hotel & Casino daily breakfast 02 Kalahari Desert Lapa Lange Lodge Service of an English speaking driver cum 03 & 04 Sossuslei Area Le Mirage Resort & Spa guide 05 & 06 Walvis Bay Lagoon Flamingo Villas Boutique Hotel Lunch and dinner as specified in the 07 Windhoe Avani Windhoek Hotel & Casino itinerary Bottled mineral water daily DAY ITINERARY Med Emergency Rescue and Evacuation 01 WINDHOEK – ARRIVAL (D) within Namibia Arrived at Windhoek Airport, meet and greet by local representative and transfer to Value Added Tax Tourism Levy hotel for check in. PRICE EXCLUSIONS 02 WINDHOEK – MARIENTAL (B/L/D) International airfare Morning depart south to Kalahari Desert. Afternoon nature Sundowner Drive. After Applicable airport taxes dinner enjoy the clear night skies with star gazing (subject to weather condition). Personal Incidental Expenses Travel Insurance 03 MARIENTAL – SOSSUSVLEI (B/L/D) Gratuities to guide & driver : Morning walk with SAN Bushman family. Later depart to Namib Desert en-route visit US$20 per person per day – pay direct the Duwisib Castle. Arrive at Sossusvlei and check in hotel. Evening Sunset Quad REMARKS Bike Trip. Tour prices quoted are subject to change 04 SOSSUSVLEI (B/L/D) with or without prior notice Visit Dunes at Sossusvlei, Dead Vlei, Dune45 & Sesriem Canyon Subject to availability upon making reservation 05 SOSSUSVLEI – WALVIS BAY (B/L/D) No refund for un-utilized tours or services Cross the Tropic of Capricorn through the Kuiseb Pass , Kuiseb Canyon, the Moon Terms & Conditions Apply Landscape and the Welwitschia Plains. -

Housing Index Third Quarter 2015

Housing Index Third quarter 2015 Published by: FNB Namibia Address: First City Centre, Levinson Arcade, Windhoek Authored by: Daniel Kavishe Tel: +264 61 2992725 Fax: +264 61 225994 Methodology: The FNB House Price Index is based on the median house price from Deeds Office data. Disclaimer: The information in this publication is derived from sources which are regarded as accurate and reliable, is of general nature only, does not constitute advice and may not be applicable to all circumstances. 340 Smoothed Weighted National Housing Index (base = January 2008) 290 240 190 140 90 Value Index Volume Index 40 The third quarter of the year saw favourable volumes seeping into the market as new residential property reach completion. On a quarterly basis, the price index advanced 22%, supported mainly by price growth during September. The volume index growth edged higher than 12% which is the fastest quarterly growth since 2013. Current growth in prices stems from the Windhoek area albeit growth in volumes seems to be a result of transactions within the towns of Swakopmund and Walvis Bay. Northern towns have further drawn attraction with prices in the region edging 21.5% higher and volumes increasing by 10.1%. Central Property prices continue to climb At the end of the third quarter we found that central property prices grew substantially with data from Windhoek indicating a 27.0% growth in median prices while prices in the Okahandja area grew by 13.8%. In Gobabis, property prices grew by 16.3% while number of transactions tripled in that area. In Windhoek, prices in Academia increased by 76% pushing median prices to N$1.9mn. -

Botswana-Namibia-2-Book 1.Indb

© Lonely Planet 413 Index amoebic dysentery 392 Bathoen 55 ABBREVIATIONS animals, see also Big Five, wildlife, bats 142 B Botswana individual animals Batswana people (B) 62 N Namibia Botswana 72 Battle of Moordkoppie (N) 251 Zam Zambia endangered species 74-5, 96, 227, Battle of Waterberg (N) 206 Zim Zimbabwe 297, 321 Bayei people (B) 63 Namibia 225, 321 beaches (N) 316 safety 50 Bechuanaland Democratic Party !nara melons 335 anteaters 74 (BDP) 57 /AE//Gams Arts Festival (N) 221, antelopes 115, 116, 193 Bechuanaland People’s Party (BPP) 239, 370 architecture 57 books 313 beer A Botswana 66-7 Botswana 71 aardvarks 74 Namibia 220-1, 350, 6 Namibia 223, 316 aardwolves 225 area codes, see inside front cover Bethanie (N) 345-6 abseiling 183 Arnhem Cave (N) 342-3 bicycle travel, see cycling accommodation, see also individual art galleries Big Five 50, 72, 97, 132 locations Botswana 151 Big Tree (Zim) 195 Botswana 158-9 National Art Gallery (N) 238 bilharzia (schistosomiasis) 391 Namibia 363-5 arts, see also individual arts Bird Island (N) 327 INDEX activities, see also individual activities Botswana 66-70 Bird Paradise (N) 328 Botswana 158-60 Namibia 218-22 birds 44-7 Namibia 365-6 ATMs Botswana 74 Victoria Falls 183-5 Contemporary San Art Gallery & Namibia 226 Africa fish eagles 45, 44 Craft Shop 165 bird-watching African wild dogs 116, 117, 132, Namibia 372 Botswana 103, 115, 132, 134, 136, 152 Attenborough, David 316 136 Agate Bay (N) 351 Aus (N) 347 Namibia 152, 267-8 Agricultural Museum (N) 346 Aus-Lüderitz Rd (N) 347-8 Zambia 183 Aha Hills -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$9.60 WINDHOEK - 4 September 2020 No. 7328 Advertisements PROCEDURE FOR ADVERTISING IN 7. No liability is accepted for any delay in the publi- THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE cation of advertisements/notices, or for the publication of REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. such on any date other than that stipulated by the advertiser. Similarly no liability is accepted in respect of any editing, 1. The Government Gazette (Estates) containing adver- revision, omission, typographical errors or errors resulting tisements, is published on every Friday. If a Friday falls on from faint or indistinct copy. a Public Holiday, this Government Gazette is published on the preceding Thursday. 8. The advertiser will be held liable for all compensa- tion and costs arising from any action which may be insti- 2. Advertisements for publication in the Government tuted against the Government of Namibia as a result of the Gazette (Estates) must be addressed to the Government Ga- publication of a notice with or without any omission, errors, zette office, Private Bag 13302, Windhoek, or be delivered lack of clarity or in any form whatsoever. at Justitia Building, Independence Avenue, Second Floor, Room 219, Windhoek, not later than 12h00 on the ninth 9. The subscription for the Government Gazette is working day before the date of publication of this Govern- N$4,190-00 including VAT per annum, obtainable from ment Gazette in which the advertisement is to be inserted. Solitaire Press (Pty) Ltd., corner of Bonsmara and Brahman Streets, Northern Industrial Area, P.O. Box 1155, Wind- 3. -

Advocacy in Action: a Guide to Influencing Decision-Making In

ADVOCACY IN ACTION A guide to influencing decision-making in Namibia Gender Research and Advocacy Project LEGAL ASSISTANCE CENTRE Windhoek 2004 Updated 2007 This publication was developed with assistance and support from the following organisations: National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) through a grant from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Women’s Legal Rights Initiative through a grant from USAID. This publication, was made possible through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS his publication was prepared by the Legal Assistance Centre with support from the Tfollowing organisations: Austrian Development Cooperation, the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) through a grant from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Women’s Legal Rights Initiative through a grant from USAID. This manual was written by Dianne Hubbard and Delia Ramsbotham of the Legal Assistance Centre, and illustrated by Nicky Marais. The following persons provided research for the manual: Dianne Hubbard, Legal Assistance Centre Delia Ramsbotham, Legal Assistance Centre, intern through the Young Professionals International Internship Program of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade of Canada, coordinated through the Canadian Bar Association Maria-Laure Knapp, Legal Assistance Centre, intern in a program of Youth International Internship Programme (YIIP) of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) of Canada, coordinated through Acadia University in Canada Evelyn Zimba, Legal Assistance Centre Anne Rimmer, a Development Worker funded by International Cooperation for Development (ICD) through the Catholic Institute for International Relations (CIIR). -

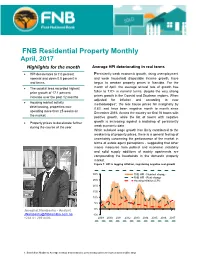

Housing Index in Due Course to Provide a Comparable Sectional Property Index

FNB Residential Property Monthly April, 2017 Highlights for the month Average HPI deteriorating in real terms HPI decelerates to 7.0 percent Persistently weak economic growth, rising unemployment nominal and down 0.8 percent in and weak household disposable income growth, have real terms. begun to weaken property prices in Namibia. For the The coastal area recorded highest month of April, the average annual rate of growth has price growth of 17.1 percent fallen to 7.0% in nominal terms, despite the very strong increase over the past 12 months prices growth in the Coastal and Southern regions. When adjusted for inflation and according to new Housing market activity methodologies¹, the real house prices fell marginally by deteriorating, properties now 0.8% and have been negative month to month since spending more than 25 weeks on December 2016. Across the country we find 16 towns with the market. positive growth, while the list of towns with negative Property prices to decelerate further growth is increasing against a backdrop of persistently during the course of the year. weak economic data. While subdued wage growth has likely contributed to the weakening of property prices, there is a general feeling of uncertainty concerning the performance of the market in terms of estate agent perceptions - suggesting that other macro measures from political and economic instability and solid supply additions of mainly apartments are compounding the headwinds in the domestic property market. Figure 1: HPI is lagging inflation, registering negative real growth 30% FNB HPI - Nominal change FNB HPI - Real change 25% Housing Inflation (CPI) 20% 15% 10% 5% Josephat Nambashu - Analyst 0% [email protected] -5% +264 61 299 8496 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 1.