Aspects of Urban Change in Windhoek, Namibia, Aspects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDE to CIVIL SOCIETY in NAMIBIA 3Rd Edition

GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA GUIDE TO 3Rd Edition 3Rd Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono and Naita Marowa PJ Rejoice Compiled by GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA 3rd Edition AN OVERVIEW OF THE MANDATE AND ACTIVITIES OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN NAMIBIA Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA COMPILED BY: Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono PUBLISHED BY: Namibia Institute for Democracy FUNDED BY: Hanns Seidel Foundation Namibia COPYRIGHT: 2018 Namibia Institute for Democracy. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means electronical or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission of the publisher. DESIGN AND LAYOUT: K22 Communications/Afterschool PRINTED BY : John Meinert Printing ISBN: 978-99916-865-5-4 PHYSICAL ADDRESS House of Democracy 70-72 Dr. Frans Indongo Street Windhoek West P.O. Box 11956, Klein Windhoek Windhoek, Namibia EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.nid.org.na You may forward the completed questionnaire at the end of this guide to NID or contact NID for inclusion in possible future editions of this guide Foreword A vibrant civil society is the cornerstone of educated, safe, clean, involved and spiritually each community and of our Democracy. uplifted. Namibia’s constitution gives us, the citizens and inhabitants, the freedom and mandate CSOs spearheaded Namibia’s Independence to get involved in our governing process. process. As watchdogs we hold our elected The 3rd Edition of the Guide to Civil Society representatives accountable. -

Two Revolutions Behind: Is the Ethiopian Orthodox Church an Obstacle Or Catalyst for Social Development?’1

Scriptura 81 (2002), pp. 378-390 ‘TWO REVOLUTIONS BEHIND: IS THE ETHIOPIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH AN OBSTACLE OR CATALYST FOR SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT?’1 JA Loubser University of Zululand Abstract As part of a project to investigate the spiritual and moral roots for an African Renaissance the paper employs an inter-disciplinary approach, investigating the intersection between religion and social development. This is done with reference to developmental issues as they become manifest in Ethiopia. An analysis of the social role of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is accompanied by a critical review of some theories and strategies for social development. Since Ethiopia is one of the major beneficiaries of US and international aid the paper also considers options for sustainable social development. 1. Introduction This paper is the direct result of a confrontation with the poverty and desperation experienced during a field trip to Ethiopia.2 While investigating the Ethiopian Orthodox tradition as part of a university project on the moral and spiritual roots for an African Renaissance, we did not expect such wide-scale poverty and human need in a country that is noteworthy for its contribution to global culture. Of the 80% population of the planet marginalized by the global economy, the people of Ethiopia count among those who are the worst off.3 The plight of its circa 60 million people with more than 80 different ethnic groups is highlighted by the following: 440 000 new cases of HIV infection (with the virulent heterosexual C-strain) were estimated for 1999;4 vast sections of the predominantly rural population are without access to basic medical care; seasonal famine regularly affects large sections of the population (4 million Ethio- pians are dependent on foreign aid for food);5 half of the children under five are estimated to be malnourished.6 outside the major towns and cities the transport infrastructure is in serious disrepair. -

Deconstructing Windhoek: the Urban Morphology of a Post-Apartheid City

No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 Working Paper No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Contents PREFACE 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 2. WINDHOEK CONTEXTUALISED ....................................................................... 2 2.1 Colonising the City ......................................................................................... 3 2.2 The Apartheid Legacy in an Independent Windhoek ..................................... 7 2.2.1 "People There Don't Even Know What Poverty Is" .............................. 8 2.2.2 "They Have a Different Culture and Lifestyle" ...................................... 10 3. ON SEGREGATION AND EXCLUSION: A WINDHOEK PROBLEMATIC ........ 11 3.1 Re-Segregating Windhoek ............................................................................. 12 3.2 Race vs. Socio-Economics: Two Sides of the Segragation Coin ................... 13 3.3 Problematising De/Segregation ...................................................................... 16 3.3.1 Segregation and the Excluders ............................................................. 16 3.3.2 Segregation and the Excluded: Beyond Desegregation ....................... 17 4. SUBURBANISING WINDHOEK: TOWARDS GREATER INTEGRATION? ....... 19 4.1 The Municipality's -

Assessing Adherence to Antihypertensive Therapy in Primary Health Care in Namibia: Findings and Implications

Cardiovasc Drugs Ther DOI 10.1007/s10557-017-6756-8 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Assessing Adherence to Antihypertensive Therapy in Primary Health Care in Namibia: Findings and Implications M. M. Nashilongo1 & B. Singu1 & F. Kalemeera1 & M. Mubita1 & E. Naikaku1 & A. Baker2 & A. Ferrario3 & B. Godman2,4,5 & L. Achieng6 & D. Kibuule1 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract variance. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.695. None of the 120 Introduction Namibia has the highest burden and incidence of patients had perfect adherence to antihypertensive therapy, hypertension in sub-Sahara Africa. Though non-adherence to and less than half had acceptable levels of adherence antihypertensive therapy is an important cardiovascular risk (≥ 80%). The mean adherence level was 76.7 ± 8.1%. factor, little is known about potential ways to improve adher- Three quarters of patients ever missed their scheduled ence in Namibia following universal access. The objective of clinic appointment. Having a family support system this study is to validate the Hill-Bone compliance scale and (OR = 5.4, 95% CI 1.687–27.6, p = 0.045) and attendance determine the level and predictors of adherence to antihyper- of follow-up visits (OR = 3.1, 95% CI 1.1–8.7, p =0.03) tensive treatment in primary health care settings in sub-urban were significant predictors of adherence. Having HIV/ townships of Windhoek, Namibia. AIDs did not lower adherence. Methods Reliability was determined by Cronbach’s alpha. Conclusions The modified Namibian version of the Hill- Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to assess con- Bone scale is reliable and valid for assessing adherence to struct validity. -

South African Airways Timetable

102 103 SAA / OUR FLIGHTS OUR FLIGHTS / SAA SOUTH AFRICAN AIRWAYS TIMETABLE As Africa’s most-awarded airline, SAA operates from Johannesburg to 32 destinations in 22 countries across the globe Our extensive domestic schedule has a total Nairobi, Ndola, Victoria Falls and Windhoek. SAA’s international of 284 flights per week between Johannesburg, network creates links to all major continents from our country Cape Town, Durban, East London and Port through eight direct routes and codeshare flights, with daily Elizabeth. We have also extended our codeshare flights from Johannesburg to Frankfurt, Hong Kong, London REGIONAL agreement with Mango, our low-cost operator, (Heathrow), Munich, New York (JFK), Perth, São Paulo and CARRIER FLIGHT FREQUENCY FROM DEPARTS TO ARRIVES to include coastal cities in South Africa (between Washington (Dulles). We have codeshare agreements with SA 144 1234567 Johannesburg 14:20 Maputo 15:20 Johannesburg and Cape Town, Durban, Port Elizabeth and 29 other airlines. SAA is a member of Star Alliance, which offers SA 145 1234567 Maputo 16:05 Johannesburg 17:10 George), as well as Johannesburg-Bloemfontein, Cape Town- more than 18 500 daily flights to 1 321 airports in 193 countries. SA 146 1234567 Johannesburg 20:15 Maputo 21:15 Bloemfontein and Cape Town-Port Elizabeth. Regionally, SAA SAA has won the “Best Airline in Africa” award in the regional SA 147 1234567 Maputo 07:30 Johannesburg 08:35 offers 19 destinations across the African continent, namely Abidjan, category for 15 consecutive years. Mango and SAA hold the SA 160 1.34567 Johannesburg 09:30 Entebbe 14:30 Accra, Blantyre, Dakar, Dar es Salaam, Entebbe, Harare, Kinshasa, number 1 and 2 spots as South Africa’s most on-time airlines. -

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE of the REPUBLIC of NAMIBIA No

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA No. 1820 N$2.12 WINDHOEK - 20 March 1998 Advertisements 7. No liability is accepted for any delay in the publication of advertisements/notices, or for the publication of such or any date other than that stipulated by the advertiser. Similarly no liability is accepted in respect of any editing, revision, PROCEDURE FOR ADVERTISING IN THE omission, typographical errors or errors resulting from faint GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC or indistinct copy. OF NAMIBIA 8. The advertiser will be held liable for all compensation and costs arising from any action which may be instituted 1. The Government Gazette (Estates) containing against the Government of Namibia as a result of the advertisements, is published on every Friday. If a Friday falls publication of a notice with or without any omission, errors, on a Public Holiday, this Government Gazette is published on lack of clarity or in any form whatsoever. the preceding Thursday. 9. The subscription for the Government Gazette is 2. Advertisements for publication in thc Government N$474,24 plus GST per annum, obtainable from Central Gazette (Estates) must be addressed to the Government Gazette Bureau Services (Pty) Ltd., Shop 3, Frans Indongo Gardens, Office, P.B. 13302, Windhoek, or be delivered at Cohen P.O. Box 1155, Windhoek. Postage must be prepaid by all Building, Ground Floor, Casino Street entrance, Windhoek, subscribers. Single copies of the Government Gazette are not later than 15:00 on the ninth working day before the date obtainable from Central Bureau Services (Pty) Ltd., Shop 3, of publication of this Government Gazette in which the Frans Indongo Gardens, P.O.Box 1155,Windhoek, at the price advertisement is to be inserted. -

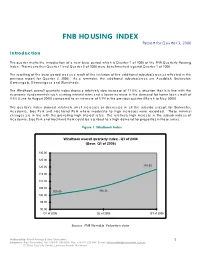

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006 Introduction This quarter marks the introduction of a new base period which is Quarter 1 of 2006 of the FNB Quarterly Housing Index. This means that Quarter 2 and Quarter 3 of 2006 were benchmarked against Quarter 1 of 2006. The resetting of the base period was as a result of the inclusion of five additional suburbs/areas as reflected in the previous report for Quarter 2, 2006. As a reminder, the additional suburbs/areas are Auasblick, Brakwater, Goreangab, Okuryangava and Wanaheda. The Windhoek overall quarterly index shows a relatively slow increase of 11.6%, a situation that is in line with the economic fundamentals such as rising interest rates and a lower increase in the demand for home loan credit of 3.6% (June to August 2006) compared to an increase of 5.9% in the previous quarter (March to May 2006). This quarter’s index showed relatively small increases or decreases in all the suburbs except for Brakwater, Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park where moderate to high increases were recorded. These minimal changes are in line with the prevailing high interest rates. The relatively high increase in the suburb indices of Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park could be ascribed to a high demand for properties in these areas. Figure 1: Windhoek Index Windhoek overall quarterly index - Q3 of 2006 (Base: Q1 of 2006) 130.00 125.00 120.00 118.55 115.00 110.00 105.00 100.00 106.22 100.00 95.00 90.00 Q1 of 2006 Q2 of 2006 Q3 of 2006 Source: FNB Namibia Valuation data Authored by: Martin Mwinga & Alex Shimuafeni 1 Enquiries: Alex Shimuafeni, Tel: +264 61 2992890, Fax: +264 61 225 994, E-mail: [email protected] 5th Floor, First City Centre, Levinson Arcade, Windhoek Brakwater recorded an extraordinary high quarterly increase of 72% from Quarter 2. -

African Newspapers: the British Library Collection from Culture to History to Geopolitics

African Newspapers: The British Library Collection From culture to history to geopolitics Quick Facts A unique database of 19th-century African newspapers offering all-new coverage Created in partnership with the British Library and its world-renowned curators An invaluable historical record for students and scholars in dozens of academic disciplines Overview African Newspapers: The British Library Collection features 64 newspapers from across the African continent, all published before 1900. Originally archived by the British Library—the national library of the United Kingdom and one of the largest and most respected libraries in the world—these rare historical documents are now available for the first time in a fully searchable online collection. From culture to history to geopolitics, the pages of these newspapers offer fresh research opportunities for students and scholars interested in topics related to Africa. An unmatched chronicle of African history Because Africa produced comparatively few newspapers in the 19th century, each page in this collection is significant, offering invaluable insight into the people, issues and events that shaped the continent. Through eyewitness reporting, editorials, letters, advertisements. obituaries and military reports, the newspapers in this one-of-a-kind collection chronicle African history and daily life as never before. Students and researchers will find news and analysis covering the European exploration of Africa, colonial exploitation, economics, Atlantic trade, the mapping of the continent, early moves towards self-governance, the growth of South Africa and much more. Created in partnership with the British Library The British Library’s incomparable collection of African newspapers is the result of the close and often controversial relationships between Great Britain and African nations during the period of colonial rule. -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

The Visual Archive of Colonialism: Germany and Namibia

Photo-essay The Visual Archive of Colonialism: Germany and Namibia George Steinmetz and Julia Hell Colonial memories and images occupy a paradoxi- cal place in Germany. This is due in part to the peculiarities of German colo- nial history, but it also reflects another aspect of German exceptionalism — the legacy of Nazism and the Holocaust. In recent years German colonialism in Southwest Africa (Namibia) has been widely discussed, especially with respect to the attempted extermination of the Ovaherero people in 1904. For reasons explored in this article, these discussions of Germany’s involvement in Southwest Africa have created new and unexpected discursive connections that are reshap- ing colonial memories in both Germany and Namibia. One possible outcome could be a belated decolonization of the landscape of colonial memory in both countries. Postwar Germany was long preoccupied with its National Socialist prehistory; the German colonial past has only started to come into focus more recently.1 The years 2004 – 5 saw numerous commemorative events around the centenary of the 1904 German genocide of the Namibian Ovaherero people and the completion of the controversial Berlin Holocaust Memorial. On one level this is mere coinci- dence. At the same time, there is an increasing entanglement of these two central political topics. But little research has been done on the visual archive of German colonialism, in contrast to the extensive studies made of the public circulation of Thanks to Johannes von Moltke for helping us with the research into the November 2004 von Trotha – Maherero meeting. 1. For a discussion of the ways in which the formerly divided country’s Nazi past was thematized anew after 1989, see Julia Hell and Johannes von Moltke, “Unification Effects: Imaginary Land- scapes of the Berlin Republic,” in “The Cultural Logics of the Berlin Republic,” ed. -

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location Henning Melber1 Abstract The Windhoek Old Location refers to what had been the South West African capital’s Main Lo- cation for the majority of black and so-called Colored people from the early 20th century until 1960. Their forced removal to the newly established township Katutura, initiated during the late 1950s, provoked resistance, popular demonstrations and escalated into violent clashes between the residents and the police. These resulted in the killing and wounding of many people on 10 December 1959. The Old Location since became a synonym for African unity in the face of the divisions imposed by apartheid. Based on hitherto unpublished archival documents, this article contributes to a not yet exist- ing social history of the Old Location during the 1950s. It reconstructs aspects of the daily life among the residents in at that time the biggest urban settlement among the colonized majority in South West Africa. It revisits and portraits a community, which among former residents evokes positive memories compared with the imposed new life in Katutura and thereby also contributed to a post-colonial heroic narrative, which integrates the resistance in the Old Location into the patriotic history of the anti-colonial liberation movement in government since Independence. O Lord, help us who roam about. Help us who have been placed in Africa and have no dwelling place of our own. Give us back a dwelling place.2 The Old Location was the Main Location for most of the so-called non-white residents of Wind- hoek from the early 20th century until 1960, while a much smaller location also existed until 1961 in Klein Windhoek. -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order.