Introduction Endeavour Foundation Wishes to Make a Submission to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Picture Perfect Views Could Be Yours Coastal Meets Country – This Is Your Slice of Paradise

Lottery #437 WIN A NEW FUTURE PICTURE PERFECT VIEWS COULD BE YOURS COASTAL MEETS COUNTRY – THIS IS YOUR SLICE OF PARADISE BUY TICKETS NOW endeavourlotteries.com.au 1800 63 40 40 BREWING UP NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR EMMA When it comes to major milestones in our lives, learning to drive and finding a job you love are definitely up there. For Bundaberg local, Emma, hitting these milestones has been a goal for many years. Now the 39-year-old has her learner’s licence in hand, is on her way to becoming a certified barista, and is enrolled in a hospitality course at TAFE. Emma has an intellectual disability and engages Endeavour Foundation’s Bundaberg Learning and Lifestyle day service to support her to achieve her goals to become more independent, confident and increase her social interaction skills. “When I started going to the service in 2019, I thought I’ll make tea and coffees for everyone, and I’ve been doing that for a very long time,” Emma said. That initial idea grew into Emma making americanos, mochas and cappuccinos topped with her own latte foam hearts. As a lifelong learner Emma has a certificate in food safety and hygiene, horticulture, and a general safety induction in the construction industry. “The plan is to work in a café making coffees for the community when I finish my course,” Emma said. Endeavour Foundation helped Emma learn the basics during the barista program: taking a customer’s order, using the cash register, and completing the order whilst having a small conversation with the customer. -

Kingaroy's Cooking Page 4

Oneautumn 2017 Endeavour Kingaroy's cooking page 4 autism awareness PAGe 2-3 Accommodation PAGE 8-9 autism awareness month Max Tindall As part of autism awareness month, adeane tindall shares the story of her son max and Looking the importance of support for ‘invisible’ disabilities. “If you walk into our home or Max’s classroom, beyond the you couldn’t pick him out as having Autism. But then we’ve funded nearly ten years of support – from speech and occupational therapy to psychology appointments. I can tell you now, he’d be a very different child if we hadn’t been in surface the position to do so.” Adeane Tindall’s 13 year old son, Max, was diagnosed with Autism at the age of four, but it was an uphill struggle. 2 | One Endeavour autism awareness month “We know that Max’s disability isn’t visible, but that doesn’t make it any less real. In fact, it’s tackling the issue head-on that has enabled him to achieve so much.” For many people with an intellectual disability, brain injury or mental health condition, the impact of an ‘invisible’ disability is significant. Social Stories It’s relatively clear when someone uses a hearing aid, guide dog or wheelchair, and it’s equally clear that a response – from friends, neighbours or the community – is required. The hearing aid prompts Some people with autism struggle with an adjustment in our communication style; the guide new social situations and social skills. dog reminds us to avoid visual communication; and the wheelchair guides us away from stairs. -

Win a New Future

Lottery #435 WIN A NEW FUTURE #435_Brochure.indd 1 8/03/2021 2:07:45 PM CELEBRATING 70 YEARS OF SUPPORTING PEOPLE WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY $100 $60 $50 $30 $10 Scotty (centre) and his housemates have been taking daily walks so *$70 for 21 tickets not available for ongoing Star Supporter memberships. they can check on the progress of their new home. BUY TICKETS NOW endeavourlotteries.com.au 1800 63 40 40 #435_Brochure.indd 2 8/03/2021 2:07:48 PM Your support is helping to build accessible homes! SCOTTY CAN’T WAIT TO MOVE INTO HIS NEW HOME In fact, he walks past the construction site nearly every day with his housemates, to check how it’s going. Scotty is one of more than 350 people with intellectual disability who will benefit from Endeavour Foundation’s landmark My Home, My Life initiative. We believe people with disability in Australia have the same right to the safety and comfort of having a permanent roof over their head as anyone else. However, we know there are simply not enough suitable homes for people like Scotty in Australia right now and demand is still growing. Thanks to your support, we’re taking action to tackle the accessible housing shortage. My Home, My Life is the biggest initiative in our 70-year history. We’re investing more than $35 Million in purpose-built accessible homes over three years, giving hundreds of Australians with intellectual disability the choice to live more independently. With your support, we’re building 59 brand new homes and refurbishing a further 26 to the platinum standard of the Livable Housing Australia guidelines. -

Anastasi Blooms' Ruby Passion Sunflowers Blossom

weekenderSaturday 25 July 2020 Anastasi Blooms’ Ruby Passion Sunflowers blossom Outpouring of community support for backpackers Streetscape pivotal to Gin Gin progress Skating at Bargara popularity grows contents Outpouring of community support for 3 backpackers Cover story Anastasi Blooms’ 4 Ruby Passion Sunflowers blossom What’s on in the Bundaberg 6 Region Sea change opportunity with 7 Bargara kiosk Workers back in staged restart at 8 Endeavour Foundation Streetscape pivotal to 9 Gin Gin progress The Grand Hotel makeover and restoration 10 underway Chilli Vodka and new Chocolate Chilli 12 Liqueur hot to go Photo of the week Thank you to Morgan Everett New pickles eggplant hits the 14 shelf at Vintners’s Secret Skating at Bargara 17 popularity grows Everyone is welcome at 18 Alice McLaughlin’s Wonderland 20 In our garden COMMUNITY Federal Backpacker fire. Photo courtesy of Jack Dempsey’s facebook page. Outpouring of community support for backpackers Trish Mears The Bundaberg Region community Community members are also urged to not has once again shown their generosity, donate items directly to hostels, as they are currently at capacity for donated goods. offering help for the Federal A co-ordination centre has been set up at Lifeline Backpackers fire victims. Bundaberg, 8 Queen Street, North Bundaberg. Several local businesses have already helped Those wishing to donate can assist by providing the following items: the displaced backpackers with food, clothing, bedding and toiletries. • Wide-brimmed, straw hats All backpackers have been found alternate • Vouchers/gift cards in lieu of cash donations - accommodation and are being well looked after. to enable the backpackers to purchase items to meet their individual needs. -

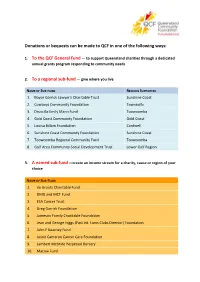

Donations Or Bequests Can Be Made to QCF in One of the Following Ways

Donations or bequests can be made to QCF in one of the following ways: 1. To the QCF General Fund — to support Queensland charities through a dedicated annual grants program responding to community needs 2. To a regional sub-fund — give where you live NAME OF SUB-FUND REGIONS SUPPORTED 1. Boyce Garrick Lawyer's Charitable Trust Sunshine Coast 2. Cowboys Community Foundation Townsville 3. Druscilla Emily Mann Fund Toowoomba 4. Gold Coast Community Foundation Gold Coast 5. Louisa Billam Foundation Cardwell 6. Sunshine Coast Community Foundation Sunshine Coast 7. Toowoomba Regional Community Fund Toowoomba 8. Gulf Area Community Social Development Trust Lower Gulf Region 3. A named sub-fund —create an income stream for a charity, cause or region of your choice NAME OF SUB-FUND 1. de Groots Charitable Fund 2. DMG and MCT Fund 3. ESA Cancer Trust 4. Greg Garrick Foundation 5. Jameson Family Charitable Foundation 6. Jean and George Higgs (Past Int. Lions Clubs Director) Foundation 7. John F Kearney Fund 8. Justin Cameron Cancer Care Foundation 9. Lambert McBride Perpetual Bursary 10. Macow Fund QCF Sub-funds NAME OF SUB-FUND 11. Maroochy Achievers Award Fund 12. McMurdo Family Fund 13. Neil H Davis QUT Bursary Fund 14. Qantaslink Torres Strait Community Trust 15. QIC Charitable Fund 16. Queensland Teachers' Union Trust 17. Renouf Family Fund 18. Roy and Nola Thompson Family Charitable Fund 19. Susannah Roberts Charitable Trust 20. The Christopher Chee Foundation Trust 21. The Robert Day Philanthropic Fund 22. The Sanderson Family Trust 23. The Strategic Environmental Fund 4. A sub-fund in memoriam – create a legacy to honour a loved one. -

MAKING a DIFFERENCE in the LIVES of PEOPLE with a DISABILITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 the Endeavour Foundationfocus Contents

To exit the Interactive Annual Report, please press ESC. MAKING A DIFFERENCE IN THE LIVES OF PEOPLE WITH A DISABILITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 THE endeavour FoundationFOCUS CONTENTS Year in review We want to enrich their lives and the lives of their 1 families and engage and educate the community about disability. 4 Chairman’s report We have an obligation to do this in a financially Endeavour Foundation’s responsible manner. 5 Chief Executive Officer’s report focus is to PROVIDE We aim to: OPPORTUNITIES 7 Disability services » Be recognised as a quality provider of FOR PEOPLE WITH so they A DISABILITY services to people with a disability. 11 Employment services may participate in the every » Be an advocate for people with a disability and their families in the Leadership day life of the community. 13 broader community. 15 Community engagement 17 Commercial operations 18 Fundraising activities 21 Funding and grants * WITH YOUR SUPPORT WE PROVIDE : 24 Our people 27 Corporate governance 2,104 people with employment and training opportunities 31 Governance chart 563 people with accommodation 33 Board of Directors 295 people with support to live in their own homes 35 Executive Management 270 adults and children with respite care 38 Locations 785 people with learning and lifestyle options 39 Financial overview 192 people with Post-School Services 44 Concise financial report 54 people with tertiary education through Latch-On® and CLUE programmes 45 Our history 15 children with vacation care 13 people with aged care *Correct as at 30 June 2010 -

Moving with the Times | PAGE 8

endeavour Moving with the times | PAGE 8 Autumn 2015 From the Chairman In this edition: Around Keon Park 3 and CEO New friends in N.T. 4 We never New challenges Senator Fifield visit 5 forget what are always Latch-On® at ten 7 we do welcome My home in Adelaide 8 The National Disability Insurance Scheme Endeavour Foundation has always been Being app-y 10 (NDIS) has brought into sharp focus the open to ideas. We are here today because ambition and determination of Endeavour our families were prepared to peer over the Foundation. While we are not afraid to fence and embrace new ways of working explore new avenues, we must always to achieve better outcomes for people we remember that people are at the heart of support. This is what makes our proposed our thinking. amalgamation with Carpentaria Disability Have Our plans and decisions are examined Services (CDS) in the Northern Territory in detail. All developments have solid so refreshing. your foundations aimed at improving the The National Disability Insurance say quality of life of the people we support. Scheme (NDIS) is gradually unfolding. With this in mind, Endeavour Foundation Organisations are building services and continues to grow because it must be in a entering new markets. The boundaries strong position to meet the demands and are moving on geographical and business competition brought about by the NDIS. levels, and Endeavour Foundation must Our survey asked: What While we began as a Queensland- adapt and move with the times. do you want to know about based organisation we never forget that We are taking a significant step forward we grew thanks to colleagues based in with CDS in the Northern Territory. -

Our Endeavour

2011-2012 ANNUAL REPORT Your choices Your support Your success Our endeavour Contents Chairman’s Report 2 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 3 Year in Review 4 Disability Services 8 Commercial Operations 12 Fundraising Activities 16 Community Engagement & Events 20 Funding & Grants 24 Accommodation 26 Leadership & Innovation 29 Human Resources 37 & Organisational Development Your opportunity to donate 39 Corporate Governance 41 Board of Directors 48 Executive Management 50 Financial Overview 52 Summary Financial Report 58 Corporate Information 74 Life is a beach for mates Grant Stevens (left) and Matt Creswick (right), who live and work on the gorgeous Gold Coast. Grant is a familiar face at Burleigh Heads business service, where he’s worked since 1984. A typical working day includes packing and sealing bottle tops or helping with mailouts. He reckons the job has helped him hone his skills over the years. “I enjoy everything about working here... the work I do and talking to the people I work with,” he says. Grant shares a unit with three housemates and says living independently has had a positive influence on him. “I’ve learned how to get along with all kinds of people and I love where I live,” he reveals. A favourite pastime is walking on the beach near home, but Grant also enjoys travelling overseas, visiting family and eating out. Matt Creswick has worked with Grant since January 2011 and has busy days packaging, pallet wrapping and sealing products. “Since I started, my skills in all areas are growing and I’m learning new things every day,” he says. -

Fundraising Goals That Have Been Identified by Local Disability and Community Service Providers

Every year, fundraising from Great Endeavour Rally participants makes a real difference to the lives of people with a disability. Endeavour Foundation is inundated with a list of fundraising goals that have been identified by local disability and community service providers. This year, we aim to raise more than $300,000 to support 740 people with a disability across Queensland, Victoria, and New South Wales. Thanks to your amazing fundraising, thousands of people with a disability will benefit in the following ways. Facilities: Fundraising Objective Location Service People Funds Offered Supported Required ($) 1 Refit Laundry Bundaberg Endeavour Employment 75 $8,000 Foundation Industries (EFI) 2 Sensory room Hervey Bay Learning & Education 2 $10,400 Lifestyle 3 Permanent gazebo and repaving Rockhampton Learning & Education 27 $20,000 Lifestyle Home & Lifestyle: Fundraising Objective Location Service Offered People Funds Supported Required ($) 4 Supported Employee Bowen & Mackay EFI’s Employment 66 $5,750 lunchroom appliances 5 Endeavour Foundation Applications open Opportunity 3 $23,995 Customers on Rally nationally 6 Airconditioning Wacol EFI Employment 211 $32,500 7 Independent Living Two new properties in Accommodation 8 $50,000 Technology Innisfail Equipment to enhance opportunities for employment: Fundraising Objective Location Service Offered People Funds Supported Required ($) 8 Automated Conveyor Bundaberg EFI Employment 75 $12,000 9 Labelling Machine Maroochydore EFI Employment 80 $25,000 10 Metal Detector Gympie EFI Employment 12 $25,000 11 Tamper Seal Applicator, Pallet Koen Park VIC EFI Employment 122 $27,500 Wrapper, and Label Applicator 12 Refridgerated Van Kingaroy Kitchens Employment 29 $35,000 13 Production Tables and Seven Hills NSW EFI Employment 99 $59,020 Labellng Machine For more information see over page. -

Qcidd Clinic Update

Located at the Mater Hospital, Potter Building, Annerley Rd, South Brisbane 61- 07-31632412 [email protected] Jan—Mar 2013 Our aim is to improve the health and wellbeing of adults with a developmental disability in Queensland, through multi-disciplinary research, education and clinical practice. Dear QCIDD Supporters, Hello and welcome to 2013! This year has started off with a big research BANG! We have three PhD students about to start on separate projects including the long term follow up of the CHAP, an evaluation of a Walk and Talk Program, and a roll out of Health Clinics for people with intellectual disability. We’re also farewelling six summer scholarship students who have been working hard over the past three months on QCIDD research projects. QCIDD CLINIC UPDATE Our waiting list for the clinic is well into 2013! Prof Lennox is booked until November, Dr Lane until March, Dr Eastgate mid March, and Dr Franklin is booked until December 2013. Don't let this stop you from sending in a referral or requesting appointments, be sure to ask the waitlist time for the doctor that you will be seeing. If you have any queries about the QCIDD Clinic please phone us on (07) 3163 2524 or email Julie on [email protected] The staff of QCIDD hope all of our colleagues, friends and supporters had a very Merry and safe Christmas and New Years. QCIDD is looking forward to working with you in 2013. In 2013, three PhD students will join our QCIDD research team. They will work on the following topics: “Follow-up of a comprehensive health assessment of adults with intellectual disability in a large non- government organisation” The Comprehensive Health Assessment Program (CHAP) has been shown to be effective in improving health outcomes for people with intellectual disability, especially in neglected health areas such as immunisation, vision and hearing checks. -

Qcidd Clinic Update

Located at the Mater Hospital, Potter Building, Annerley Rd, South Brisbane 61- 07-31632412 August 2011 [email protected] Vol 4, Issue 3 Our aim is to improve the health and wellbeing of adults with a developmental disability in Queensland, through multi-disciplinary research, education and clinical practice. QCIDD CLINIC UPDATE Dear QCIDD supporters, Hello, spring welcomes us to new things and new ideas. Our waiting time for the clinic is about 8 weeks at the moment. However our clinic is still ex- periencing a high demand for service. There have been a few staff changes at QCIDD over the last couple of months. These are exciting times for disability with the NDIS – National Disability Insurance Scheme recently being announced by the Federal government. In this newsletter we have asked people to share their stories with us. I think it is important to share information with each other as the journey through life with a disabled child/ adult can often be a lonely one. So please share your stories with us. If you have any queries about the QCIDD Clinic please phone us on (07) 3163 2524 or email [email protected] In this issue: Fragile X Clinical Trials Clinic update Presentations Welcome to new staff Up Coming events Farewell Books of interest Useful Websites Are you a story teller?? Share a story on your child in our newsletter! Tell a story about your child and how they are an inspiration to your family Welcome to our new staff QCIDD is fortunate to have talented new staff members. -

Let 70,000 Blossoms Bloom

WINTER 2021 My Home, My Life initiative set to improve lives PAGE 4 Imagine What’s Let 70,000 Possible competition winners announced blossoms PAGE 7 bloom PAGE 8 What’s inside Home Sweet Home Your Disability Support Pension questions answered Our My Home, My Life initiative is set to improve the lives of We’ve taken your questions, put hundreds of people with disability. our heads together and come up Read about the first 15 brand new with some answers about the homes to be finished this year and Disability Support Pension. the many more to come. Page 10 Page 4 Chris gains independence Imagine What’s with a new job Possible competition Chris lands a new job with winners announced the support of Community We invited people with intellectual Solutions Group. disability to tell us their dream Page 14 experience. Meet the five lucky winners who are on their way to living their dream. Virtual learning hub a driving Page 7 force for students Read about how school students in regional and rural Queensland Big-hearted Biloela are being transported into a community backs virtual world to clear a path for day service their future. Our new Biloela Learning and Page 16 Lifestyle day service demonstrates the power of community action to make a difference in people’s lives. Page 9 One Endeavour is the official Endeavour Foundation magazine full of news and stories featuring people with disability. facebook-square @endeavourfoundation instagram @endeavourfoundation twitter @endeavourf linkedin Endeavour Foundation Subscribe at endeavour.com.au/oneendeavour endeavour.com.au 1800 112 112 envelope [email protected] On the cover: 70,000 flowers deliver a blooming good Mother’s Day at Endeavour Foundation’s Bundaberg farm.