Viking Teesside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roseberry Topping a Short Tour of the Celebrated Landmark the Book “Roseberry Topping”

Roseberry Topping a short tour of the celebrated landmark The book “Roseberry Topping” This presentation is taken from a book, published in 2006, by the local history group Great Ayton Community Archaeology and the landscape photographer Joe Cornish, who lives in Great Ayton. All 3,000 copies of the publication were sold in six months or so, and copies rarely, if ever, appear on the second-hand market. Geology Roseberry Topping consists of almost horizontal strata arranged like a layer cake. Saltwick Sandstone cap Whitby Mudstone (with jet at lower levels) Cleveland Ironstone Staithes Sandstone Origin of the name The name Roseberry Topping derives from Othenesberg, Old Norse for the hill of Odin, named by the Scandinavian invaders. The initial “R” arose from the village of Newton-under- Roseberry, with alliteration of the “r” of “under”. Toppinn is Old Norse for hill. This became Anglicised into Topping. Roseberry is the only location in Britain to be overtly named after Odin, and was clearly held in high regards by the Scandinavians. Lord Rosebery In spite of the slightly different spelling, the title “Lord Rosebery” does derive from the Topping. The Earldom of Roseberry was created in 1703 by Queen Anne, in recognition of Sir Archibald Primrose’s support for William of Orange. The Primrose family owned land near Roseberry Topping, and thought the name “Roseberry” had a good sound to it, hence they adopted the name for the title. Over the years it lost one of its “r” letters. The Fifth Earl, shown here, is remembered for having three ambitions; to marry the richest woman in England, to become Prime Minister and to win the Derby with one of his horses. -

N. & E. Ridings Yorkshire

688 PER N. & E. RIDINGS YORKSHIRE. (KKLLY's PAwNBROKERS-continued. l\'Iaychell G. West Witton,Leyburn R.S.O Brameld Henry Edward L.R.C.P.Edin. 1 Levy Lewis, 73 & 75 Smeaton street, Nicholson David, Emgatc, Bedale M.R.c.s.Eng. (firm, Brameld & Bnr- N orth Ormesby, Middlesbrough Osguthorpe Mrs. M.A. New rd.Scarboro' nett),Balmoral ter.Saltbrn.-by-the-Sea LewisLevy,6 CargoFleet rd.:vfiddlesbro' Oxley Jn.Ihll's yard,Flowergate,Whitby Brett Francis Charles L.R.C.P.Lond. Ths McDonald Charles, 38 Cleveland street, Pepper Alfd.M.n3 Victoria rd.Scarboro' Elms, St. John's street, Bridlington South Bank R.S.O Phillip&Wright,7sAlbertrd.Middlesbro' & 9 Manor street, Bridlington Qaay Marshall William Hamblet, 98 Smeaton Pickermg Henry,44Harwick st.Scarboro' Burnett Ernest Joseph M.B., C. M. (firm, street, North Ormesby, Middlesbro' Pitchforth Thomas H. Milton street, Brameld & Burnett), II Emerald Nelson B. 63 Corporation rd. Middlesbro' Saltburn-by-the-Sea street, Saltburn-by-the-Sea Pickering John Hutchinson, 4 & 5 Mar- Raine James, 33 Barwick st.Scarborough Coates William Henry •M. A., M. B., L.SC. ket place, North Ormesby,Middlesbro' Raw F. Richmond ter. Croft, Darling-ton Patrington, Hull Plant Albt. H. West st.Eston,l\liddlesbro' Reed Edward, 45 St. John's road, Fals- Craster Edward Ernest L. R.C. P.Edin. I Sample Miss Jane & Mrs. Arabella grave, Searborough Grange road west & 1 Bridge street Hagen, 177 Cannon st. Middlesbrough HeynoldsA.4A, Valley Bridge par.Scarbro' west, Middlesbrough Sanderson Robt. High st. Loftus R.S.O Riley Ingham, Market place, Richmond Dale Frederic M. -

PEIR Appendix

Preliminary Environmental Information Report Volume III - Appendices Appendix 17A: Landscape Character The Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 (as amended) Prepared for: Net Zero Teesside Power Ltd. & Net Zero North Sea Storage Ltd. Appendix 17A Landscape Character Table of Contents 17A. Landscape Character .....................................................17-1 17.1 National ...................................................................................................... 17-1 17.2 Regional ..................................................................................................... 17-4 17.3 Local ........................................................................................................... 17-4 17.4 References ................................................................................................. 17-9 Tables Table 17A-1: NCA Summary Table ....................................................................... 17-1 Table 17A-2: MCA Summary Table (Marine Management Organisation, 2018) .... 17-3 Table 17A-3: Landscape Tracts summary table (Redcar & Cleveland Borough Council, 2006) ....................................................................................................... 17-5 Table 17A-4: Landscape Character Areas Summary Table (Stockton on Tees Borough Council, 2011) ......................................................................................... 17-7 Table 17A-5: Landscape Character Types Summary Table (Hartlepool Borough Council, 2000) -

Contaminated Land Inspection Strategy 2013

Area Management Regulatory Services Environmental Protection Contaminated Land Inspection Strategy 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On April 1st 2000, Part 2A of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 (inserted into that Act by section 57 of the Environment Act 1995) came into force. The main objective requires local authorities to take a “strategic approach” to inspecting their areas to identify land where contamination is causing unacceptable risks to human health or the wider environment. This document is the second review and sets out the manner in which Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council proposes to implement its inspection duties under Part 2A in accordance with the revised Statutory Guidance issued by the Department of Environment and Rural Affairs in April 2012 which should be read in conjunction with this Strategy. This is a comprehensive review of the Strategy to reflect the many changes in contaminated land legislation and guidance published in the last few years. Using a bespoke software package (GeoEnviron) with the Council’s GIS system, contaminated land has been identified and prioritised. The Council identified landfill sites within the borough as highest priority for inspection due to problems from landfill gas, land stability and leachate pollution, potentially posing high risks to neighbouring occupants, and therefore concentrated resources in these areas. To-date, following successful funding bids to Defra, the Council has investigated 3 former landfill sites known to have domestic waste tipped and continues to monitor and manage gas at these sites to minimise the risk to nearby residents. From the work carried out to-date, no sites have been determined as contaminated land, under the definition stated within the statutory guidance. -

Ancient Origins of Lordship

THE ANCIENT ORIGINS OF THE LORDSHIP OF BOWLAND Speculation on Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norse and Brythonic roots William Bowland The standard history of the lordship of Bowland begins with Domesday. Roger de Poitou, younger son of one of William the Conqueror’s closest associates, Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, is recorded in 1086 as tenant-in-chief of the thirteen manors of Bowland: Gretlintone (Grindleton, then caput manor), Slatebourne (Slaidburn), Neutone (Newton), Bradeforde (West Bradford), Widitun (Waddington), Radun (Radholme), Bogeuurde (Barge Ford), Mitune (Great Mitton), Esingtune (Lower Easington), Sotelie (Sawley?), Hamereton (Hammerton), Badresbi (Battersby/Dunnow), Baschelf (Bashall Eaves). William Rufus It was from these holdings that the Forest and Liberty of Bowland emerged sometime after 1087. Further lands were granted to Poitou by William Rufus, either to reward him for his role in defeating the army of Scots king Malcolm III in 1091-2 or possibly as a consequence of the confiscation of lands from Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumbria in 1095. 1 As a result, by the first decade of the twelfth century, the Forest and Liberty of Bowland, along with the adjacent fee of Blackburnshire and holdings in Hornby and Amounderness, had been brought together to form the basis of what became known as the Honor of Clitheroe. Over the next two centuries, the lordship of Bowland followed the same descent as the Honor, ultimately reverting to the Crown in 1399. This account is one familiar to students of Bowland history. However, research into the pattern of land holdings prior to the Norman Conquest is now beginning to uncover origins for the lordship that predate Poitou’s lordship by many centuries. -

Authorised Memorial Masons and Agents

Bereavement Services AUTHORISED MEMORIAL MASONS Register Office Redcar & Cleveland Leisure & Community Heart AND AGENTS Ridley Street, Redcar TS10 1TD Telephone: 01642 444420/21 T The memorial masons on this list have agreed to abide by the Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council Cemetery Rules and Regulations for the following cemeteries: Boosbeck, Brotton, Eston, Guisborough, Loftus, Redcar, Saltburn and Skelton. They have agreed to adhere to the Code of Practice issued by the National Association of Memorial Masons (NAMM) and have complied with all our registration scheme requirements. Funeral Directors and any other person acting as an agent should ensure that their contracted mason is included before processing any memorial application. This list shows those masons and the agents through their masons who are registered to carry out work within our cemeteries. Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council does not recommend individual masons or agents or accept any responsibility for their workmanship. Grave owners are reminded that they own the memorial and are responsible for ensuring it remains in good repair. The Council is currently undertaking memorial safety checks and any memorial found to be unsafe or dangerous would result in the owner being contacted, where possible, and remedial action being taken. ` MEMORIAL MASONS Expiry Date Address Telephone Number Abbey Memorials Ltd 31 December 2021 Rawreth Industrial Estate, Rawreth Lane, Rayleigh, Essex SS6 9RL 01268 782757 Bambridge Brothers 31 December 2021 223 Northgate, Darlington, DL1 -

Cleveland Naturalists'

CLEVELAND NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Volume 5 Part 1 Spring 1991 CONTENTS Recent Sightings and Casual Notes CNFC Recording Events and Workshop Programme 1991 The Forming of a Field Study Group Within the CNFC Additions to Records of Fungi In Cleveland Recent Sightings and Casual Notes CNFC Recording Events and Workshop Programme 1991 The Forming of a Field Study Group Within the CNFC Additions to Records of Fungi In Cleveland CLEVELAND NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB 111th SESSION 1991-1992 OFFICERS President: Mrs J.M. Williams 11, Kedleston Close Stockton on Tees. Secretary: Mrs J.M. Williams 11 Kedleston Close Stockton on Tees. Programme Secretaries: Misses J.E. Bradbury & N. Pagdin 21, North Close Elwick Hartlepool. Treasurer; Miss M. Gent 42, North Road Stokesley. Committee Members: J. Blackburn K. Houghton M. Yates Records sub-committee: A.Weir, M Birtle P.Wood, D Fryer, J. Blackburn M. Hallam, V. Jones Representatives: I. C.Lawrence (CWT) J. Blackburn (YNU) M. Birtle (NNU) EDITORIAL It is perhaps fitting that, as the Cleveland Naturalist's Field Club enters its 111th year in 1991, we should be celebrating its long history of natural history recording through the re-establishment of the "Proceedings". In the early days of the club this publication formed the focus of information desemmination and was published continuously from 1881 until 1932. Despite the enormous changes in land use which have occurred in the last 60 years, and indeed the change in geographical area brought about by the fairly recent formation of Cleveland County, many of the old records published in the Proceedings still hold true and even those species which have disappeared or contracted in range are of value in providing useful base line data for modern day surveys. -

Community Conversations: the Responses

Community Conversations: The Responses August 2018 Hannah Roderick Middlesbrough Voluntary Development Agency Community Conversations March - July 2018 Contents Introduction 1 Who responded? 2 How did they respond? 6 Question one 7 What is life like in Middlesbrough for you and your family? Question two 11 What could be done to improve life in Middlesbrough For you, your family and others around you Question three 19 What could your role in that be? Question four 22 What would help you to do this? Question five 25 How would we know that things were improving for people in Middlesbrough? Next steps 30 2 Community Conversations March - July 2018 Introduction This report brings together the initial analysis of the responses from the Middlesbrough Community Conversations, that were hosted between March - July 2018. Volunteers or staff members from 42 different voluntary and community organisations (VCOs) asked people in their communities to answer five questions: 1. What is life like in Middlesbrough for you and your family? 2. What could be done to improve life in Middlesbrough For you, your family and others around you 3. What could your role in that be? 4. What would help you to do this? 5. How would we know that things were improving for people in Middlesbrough? 3 Community Conversations March - July 2018 Who responded? In the period March to June, the 42 VCOs spoke to 1765 people, from across all the Middlesbrough postcode areas. From May to July, members of the public, Councillors and Middlesbrough Council employees were also invited to host conversations. This resulted in a further 110 responses. -

Countryside Rights of Way Improvement Plan for the Next Five Years

SALTBURN AND DISTRICT BRIDLEWAYS GROUP Spring Newsletter 2016 Welcome to our spring newsletter. There’s never been a better time to be a member of the group – as well as exciting discounts for you, we have lots of exciting things coming up this year, including details of our ever popular pleasure ride and some great guests appearing at our public meetings. Five-year rights of way plan SADBG committee members met with Ian Tait, rights of way advisor for Redcar and Cleveland Council to discuss the area’s Countryside Rights of Way Improvement Plan for the next five years. Members were asked to produce a "wish list" which was presented to Ian, this included: Black Ash Path to St Germain’s, Marske – Split into a bridleway and a footpath? Errington Woods permissive bridleway - status change to public bridleway (formal application submitted by SADBG last year) Convert the track between the footpath and bridleway in Errington Woods into bridleway to make a loop round Pontac Road and Quarry Lane. Footpaths from Gurney Street, New Marske, to Catt Flatt Lane converted to bridleways to link with Green Lane, Redcar Creating a bridleway between proposed new housing estate and Saltburn Riding School Improve horse box parking locally Linking up existing bridleways to extend the local bridleway network including: o Mucky Lane and Errington Loop/Upleatham – via Tockett’s Mill? WEBSITE: www.saltburndistrictbridleways.co.uk EMAIL: [email protected] FIND US ON FACEBOOK AND FOLLOW US ON TWITTER @SADBG2000 o Yearby Woods to Wilton Woods or Kirkleatham to Lazenby Bank o Saltburn Riding School to Quarry Lane (SADBG already working with farmer on permissive route due to open September 2016 if all goes to plan!). -

The Benefice Profile of Yarm with Kirklevington, Picton and Worsall

The Benefice Profile of Yarm with Kirklevington, Picton and Worsall St Mary Magdalene, Yarm Aerial photographs taken by Harry Brown All Saints, Worsall A message from the Rt Revd Paul Ferguson, Bishop of Whitby Welcome, and thank you for your interest in the post of Rector of Yarm with Kirklevington, Picton and Worsall. This post offers exciting possibilities for ministry in a varied town-and-country setting. As you will read in these pages, this is a benefice of two parishes comprising the market town of Yarm and a group of nearby villages. This relatively new grouping was formed under the leadership of the previous Rector, Canon John Ford, who was also Area Dean and who retired in 2020. The communities are conscious of their very long history — Yarm is an ancient fording place over the River Tees, and the villages have been the source of a wealth of Saxon and Anglo-Danish archaeology — but they are not in any sense locked into the past. Retail and education are key to their economy and culture; rural industry still has a significant part to play, and there is extensive new house-building and an increasing population. The new Rector will find a secure foundation to build on, willing and able lay leaders, and a shared commitment to worship well planned and led in a generally liberal Catholic style. Although there is mention in this profile of concern that congregations are ageing, in fact there is more involvement with families and younger people, and with external institutions, than would be found in many other places. -

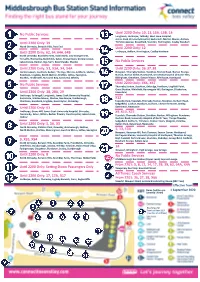

Middlesbrough Bus Station

No Public Services Until 2200 Only: 10, 13, 13A, 13B, 14 Longlands, Linthorpe, Tollesby, West Lane Hospital, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Acklam, Until 2200 Only: 39 Trimdon Avenue, Brookfield, Stainton, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Berwick Hills, Park End Until 2200 Only: 12 Until 2200 Only: 62, 64, 64A, 64B Linthorpe, Acklam, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Brambles Farm, South Bank, Low Grange Farm, Teesville, Normanby, Bankfields, Eston, Grangetown, Dormanstown, Lakes Estate, Redcar, Ings Farm, New Marske, Marske No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X3, X3A, X4, X4A Until 2200 Only: 36, 37, 38 Dormanstown, Coatham, Redcar, The Ings, Marske, Saltburn, Skelton, Newport, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Norton Road, Norton Grange, Boosbeck, Lingdale, North Skelton, Brotton, Loftus, Easington, Norton, Norton Glebe, Roseworth, University Hospital of North Tees, Staithes, Hinderwell, Runswick Bay, Sandsend, Whitby Billingham, Greatham, Owton Manor, Rift House, Hartlepool No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X66, X67 Thornaby Station, Stockton, Oxbridge, Hartburn, Lingfield Point, Great Burdon, Whinfield, Harrowgate Hill, Darlington, (Cockerton, Until 2200 Only: 28, 28A, 29 Faverdale) Linthorpe, Saltersgill, Longlands, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Marton, Nunthorpe, Guisborough, X12 Charltons, Boosbeck, Lingdale, Great Ayton, Stokesley Teesside Park, Teesdale, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Durham Road, Sedgefield, Coxhoe, Bowburn, Durham, Chester-le-Street, Birtley, Until -

Anglo–Saxon and Norman England

GCSE HISTORY Anglo–Saxon and Norman England Module booklet. Your Name: Teacher: Target: History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 Checklist Anglo-Saxon society and the Norman conquest, 1060-66 Completed Introduction to William of Normandy 2-3 Anglo-Saxon society 4-5 Legal system and punishment 6-7 The economy and social system 8 House of Godwin 9-10 Rivalry for the throne 11-12 Battle of Gate Fulford & Stamford Bridge 13 Battle of Hastings 14-16 End of Key Topic 1 Test 17 William I in power: Securing the kingdom, 1066-87 Page Submission of the Earls 18 Castles and the Marcher Earldoms 19-20 Revolt of Edwin and Morcar, 1068 21 Edgar Aethling’s revolts, 1069 22-24 The Harrying of the North, 1069-70 25 Hereward the Wake’s rebellion, 1070-71 26 Maintaining royal power 27-28 The revolt of the Earls, 1075 29-30 End of Key Topic 2 Test 31 Norman England, 1066-88 Page The Norman feudal system 32 Normans and the Church 33-34 Everyday life - society and the economy 35 Norman government and legal system 36-38 Norman aristocracy 39 Significance of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux 40 William I and his family 41-42 William, Robert and revolt in Normandy, 1077-80 43 Death, disputes and revolts, 1087-88 44 End of Key Topic 3 test 45 1 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 2 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 KT1 – Anglo-Saxon society and the Normans, 1060-66 Introduction On the evening of 14 October 1066 William of Normandy stood on the battlefield of Hastings.