Critical Species of Odonata in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mitochondrial Genomes of Palaeopteran Insects and Insights

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The mitochondrial genomes of palaeopteran insects and insights into the early insect relationships Nan Song1*, Xinxin Li1, Xinming Yin1, Xinghao Li1, Jian Yin2 & Pengliang Pan2 Phylogenetic relationships of basal insects remain a matter of discussion. In particular, the relationships among Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Neoptera are the focus of debate. In this study, we used a next-generation sequencing approach to reconstruct new mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) from 18 species of basal insects, including six representatives of Ephemeroptera and 11 of Odonata, plus one species belonging to Zygentoma. We then compared the structures of the newly sequenced mitogenomes. A tRNA gene cluster of IMQM was found in three ephemeropteran species, which may serve as a potential synapomorphy for the family Heptageniidae. Combined with published insect mitogenome sequences, we constructed a data matrix with all 37 mitochondrial genes of 85 taxa, which had a sampling concentrating on the palaeopteran lineages. Phylogenetic analyses were performed based on various data coding schemes, using maximum likelihood and Bayesian inferences under diferent models of sequence evolution. Our results generally recovered Zygentoma as a monophyletic group, which formed a sister group to Pterygota. This confrmed the relatively primitive position of Zygentoma to Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Neoptera. Analyses using site-heterogeneous CAT-GTR model strongly supported the Palaeoptera clade, with the monophyletic Ephemeroptera being sister to the monophyletic Odonata. In addition, a sister group relationship between Palaeoptera and Neoptera was supported by the current mitogenomic data. Te acquisition of wings and of ability of fight contribute to the success of insects in the planet. -

Distribution Patterns of Odonate Assemblages in Relation to Environmental Variables in Streams of South Korea

insects Article Distribution Patterns of Odonate Assemblages in Relation to Environmental Variables in Streams of South Korea Da-Yeong Lee 1, Dae-Seong Lee 1, Mi-Jung Bae 2, Soon-Jin Hwang 3 , Seong-Yu Noh 4, Jeong-Suk Moon 4 and Young-Seuk Park 1,5,* 1 Department of Biology, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea; [email protected] (D.-Y.L.); [email protected] (D.-S.L.) 2 Freshwater Biodiversity Research Bureau, Nakdonggang National Institute of Biological Resources, Sangju, Gyeongsangbuk-do 37242, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Environmental Health Science, Konkuk University, Seoul 05029, Korea; [email protected] 4 Water Environment Research Department, Watershed Ecology Research Team, National Institute of Environmental Research, Incheon 22689, Korea; [email protected] (S.-Y.N.); [email protected] (J.-S.M.) 5 Department of Life and Nanopharmaceutical Sciences, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-961-0946 Received: 20 September 2018; Accepted: 25 October 2018; Published: 29 October 2018 Abstract: Odonata species are sensitive to environmental changes, particularly those caused by humans, and provide valuable ecosystem services as intermediate predators in food webs. We aimed: (i) to investigate the distribution patterns of Odonata in streams on a nationwide scale across South Korea; (ii) to evaluate the relationships between the distribution patterns of odonates and their environmental conditions; and (iii) to identify indicator species and the most significant environmental factors affecting their distributions. Samples were collected from 965 sampling sites in streams across South Korea. We also measured 34 environmental variables grouped into six categories: geography, meteorology, land use, substrate composition, hydrology, and physicochemistry. -

Nansei Islands Biological Diversity Evaluation Project Report 1 Chapter 1

Introduction WWF Japan’s involvement with the Nansei Islands can be traced back to a request in 1982 by Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh. The “World Conservation Strategy”, which was drafted at the time through a collaborative effort by the WWF’s network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), posed the notion that the problems affecting environments were problems that had global implications. Furthermore, the findings presented offered information on precious environments extant throughout the globe and where they were distributed, thereby providing an impetus for people to think about issues relevant to humankind’s harmonious existence with the rest of nature. One of the precious natural environments for Japan given in the “World Conservation Strategy” was the Nansei Islands. The Duke of Edinburgh, who was the President of the WWF at the time (now President Emeritus), naturally sought to promote acts of conservation by those who could see them through most effectively, i.e. pertinent conservation parties in the area, a mandate which naturally fell on the shoulders of WWF Japan with regard to nature conservation activities concerning the Nansei Islands. This marked the beginning of the Nansei Islands initiative of WWF Japan, and ever since, WWF Japan has not only consistently performed globally-relevant environmental studies of particular areas within the Nansei Islands during the 1980’s and 1990’s, but has put pressure on the national and local governments to use the findings of those studies in public policy. Unfortunately, like many other places throughout the world, the deterioration of the natural environments in the Nansei Islands has yet to stop. -

ANDJUS, L. & Z.ADAMOV1C, 1986. IS&Zle I Ogrozene Vrste Odonata U Siroj Okolin

OdonatologicalAbstracts 1985 NIKOLOVA & I.J. JANEVA, 1987. Tendencii v izmeneniyata na hidrobiologichnoto s’soyanie na (12331) KUGLER, J., [Ed.], 1985. Plants and animals porechieto rusenski Lom. — Tendencies in the changes Lom of the land ofIsrael: an illustrated encyclopedia, Vol. ofthe hydrobiological state of the Rusenski river 3: Insects. Ministry Defence & Soc. Prol. Nat. Israel. valley. Hidmbiologiya, Sofia 31: 65-82. (Bulg,, with 446 col. incl. ISBN 965-05-0076-6. & Russ. — Zool., Acad. Sei., pp., pis (Hebrew, Engl. s’s). (Inst. Bulg. with Engl, title & taxonomic nomenclature). Blvd Tzar Osvoboditel 1, BG-1000 Sofia). The with 48-56. Some Lists 7 odon. — Lorn R. Bul- Odon. are dealt on pp. repre- spp.; Rusenski valley, sentative described, but checklist is spp. are no pro- garia. vided. 1988 1986 (12335) KOGNITZKI, S„ 1988, Die Libellenfauna des (12332) ANDJUS, L. & Z.ADAMOV1C, 1986. IS&zle Landeskreises Erlangen-Höchstadt: Biotope, i okolini — SchrReihe ogrozene vrste Odonata u Siroj Beograda. Gefährdung, Förderungsmassnahmen. [Extinct and vulnerable Odonata species in the broader bayer. Landesaml Umweltschutz 79: 75-82. - vicinity ofBelgrade]. Sadr. Ref. 16 Skup. Ent. Jugosl, (Betzensteiner Str. 8, D-90411 Nürnberg). 16 — Hist. 41 recorded 53 localities in the VriSac, p. [abstract only]. (Serb.). (Nat. spp. were (1986) at Mus., Njegoseva 51, YU-11000 Beograd, Serbia). district, Bavaria, Germany. The fauna and the status of 27 recorded in the discussed, and During 1949-1950, spp. were area. single spp. are management measures 3 decades later, 12 spp. were not any more sighted; are suggested. they became either locally extinct or extremely rare. A list is not provided. -

The Superfamily Calopterygoidea in South China: Taxonomy and Distribution. Progress Report for 2009 Surveys Zhang Haomiao* *PH D

International Dragonfly Fund - Report 26 (2010): 1-36 1 The Superfamily Calopterygoidea in South China: taxonomy and distribution. Progress Report for 2009 surveys Zhang Haomiao* *PH D student at the Department of Entomology, College of Natural Resources and Environment, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China. Email: [email protected] Introduction Three families in the superfamily Calopterygoidea occur in China, viz. the Calo- pterygidae, Chlorocyphidae and Euphaeidae. They include numerous species that are distributed widely across South China, mainly in streams and upland running waters at moderate altitudes. To date, our knowledge of Chinese spe- cies has remained inadequate: the taxonomy of some genera is unresolved and no attempt has been made to map the distribution of the various species and genera. This project is therefore aimed at providing taxonomic (including on larval morphology), biological, and distributional information on the super- family in South China. In 2009, two series of surveys were conducted to Southwest China-Guizhou and Yunnan Provinces. The two provinces are characterized by karst limestone arranged in steep hills and intermontane basins. The climate is warm and the weather is frequently cloudy and rainy all year. This area is usually regarded as one of biodiversity “hotspot” in China (Xu & Wilkes, 2004). Many interesting species are recorded, the checklist and photos of these sur- veys are reported here. And the progress of the research on the superfamily Calopterygoidea is appended. Methods Odonata were recorded by the specimens collected and identified from pho- tographs. The working team includes only four people, the surveys to South- west China were completed by the author and the photographer, Mr. -

The Phylogeny of the Zygopterous Dragonflies As Based on The

THE PHYLOGENY OF THE ZYGOPTEROUS DRAGON- FLIES AS BASED ON THE EVIDENCE OF THE PENES* CLARENCE HAMILTON KENNEDY, Ohio State University. This paper is merely the briefest outline of the writer's discoveries with regard to the inter-relationship of the major groups of the Zygoptera, a full account of which will appear in his thesis on the subject. Three papers1 by the writer discussing the value of this organ in classification of the Odonata have already been published. At the beginning, this study of the Zygoptera was viewed as an undertaking to define the various genera more exactly. The writer in no wise questioned the validity of the Selysian concep- tion that placed the Zygopterous subfamilies in series with the richly veined '' Calopterygines'' as primitive and the Pro- toneurinae as the latest and final reduction of venation. However, following Munz2 for the Agrioninae the writer was able to pick out here and there series of genera where the devel- opment was undoubtedly from a thinly veined wing to one richly veined, i. e., Megalagrion of Hawaii, the Argia series, Leptagrion, etc. These discoveries broke down the prejudice in the writer's mind for the irreversibility of evolution in the reduction of venation in the Odonata orders as a whole. Undoubt- ably in the Zygoptera many instances occur where a richly veined wing is merely the response to the necessity of greater wing area to support a larger body. As the study progressed the writer found almost invariably that generalized or connecting forms were usually sparsely veined as compared to their relatives. -

Are Represented by 47 Spp. India’S Independence,Pp

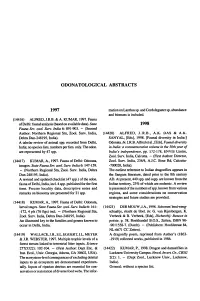

Odonatological Abstracts 1997 mation Lanthus and abundance on sp. Cordulegastersp. and biomass is included. (14416) ALFRED, J.R.B. & A. KUMAR, 1997. Fauna 1998 ofDelhi: faunal analysis (basedon available data). Slate Fauna Ser. zool. Surv. India 6: 891-903. — (Second Author: Northern Regional Stn, Zool. Surv. India, (14420) ALFRED, A.K. DAS & A.K. Dehra Dun-248195,India). SANYAL, [Eds], 1998. [Faunal diversity in India:] Odonata. In\ J.R.B. Alfred Faunal A tabelar review of animal spp. recorded from Delhi, et al., [Eds], diversity fam. The odon. in India: commemorative volume in the 50th India;no species lists, numbers per only. a year of 172-178, ENVIS Centre, are represented by 47 spp. India’s independence,pp. Zool. Surv. India, Calcutta. — (First Author: Director, (14417) KUMAR, A., 1997. Fauna of Delhi: Odonata, Zool. Surv. India, 234/4, A.J.C. Bose Rd, Calcutta- imagos. State Fauna Ser. zool. Surv. India 6: 147-159. -700020, India). in — (Northern Regional Stn, Zool. Surv. India, Dehra The earliest reference to Indian dragonflies appears Dun-248195,India). the Sangam literature, dated prior to the 8th century and known from the A revised and updatedchecklist (47 spp.) ofthe odon. AD. At present, 449 spp. sspp. are inch 4 for the first Indian 23% of which endemic. A review fauna ofDelhi, India, spp. published territory, are and is ofthe numbers of known from various time. Precise locality data, descriptive notes presented spp. for 21 remarks onbionomy are presented spp. regions, and some considerations on conservation future studies strategies and are provided. (14418) KUMAR, A., 1997. -

By the Lepidoptera (Eg Patterns Are Frequently Used

Odonatologica 15(3): 335-345 September I, 1986 A survey of some Odonata for ultravioletpatterns* D.F.J. Hilton Department of Biological Sciences, Bishop’s University, Lennoxville, Quebec, J1M 1Z7, Canada Received May 8, 1985 / Revised and Accepted March 3, 1986 series of 338 in families A museum specimens comprising spp. 118 genera and 16 were photographed both with and without a Kodak 18-A ultraviolet (UV) filter. These photographs revealed that only Euphaeaamphicyana reflected UV from its other wings whereas all spp. either did not absorb UV (e.g. 94.5% of the Coenagri- did In with flavescent. onidae) or so to varying degrees. particular, spp. orange or brown UV these wings (or wing patches) exhibited absorption for same areas. However, other spp. with nearly transparent wings (especially certain Gomphidae) Pruinose also had strong UV absorption. body regions reflected UV but the standard acetone treatment for color preservation dissolves thewax particles of the pruinosity and destroys UV reflectivity. As is typical for arthropod cuticle, non-pruinosebody regions absorbed UV and this obscured whatever color patterns might otherwise be visible without the camera’s UV filter. Frequently there is sexual dimorphismin UV and and these role various of patterns (wings body) differences may play a in aspects mating behavior. INTRODUCTION Considerable attention has been paid to the various ultraviolet (UV) patterns exhibited by the Lepidoptera (e.g. SCOTT, 1973). Studies have shown (e.g. RUTOWSKI, 1981) that differing UV-reflectance patterns are frequently used as visual in various of behavior. few insect cues aspects mating Although a other groups have been investigated for the presence of UV patterns (HINTON, 1973; POPE & HINTON, 1977; S1LBERGL1ED, 1979), little informationis available for the Odonata. -

Odonatological Abstract Service

Odonatological Abstract Service published by the INTERNATIONAL DRAGONFLY FUND (IDF) in cooperation with the WORLDWIDE DRAGONFLY ASSOCIATION (WDA) Editors: Dr. Klaus Reinhardt, Dept Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, UK. Tel. ++44 114 222 0105; E-mail: [email protected] Martin Schorr, Schulstr. 7B, D-54314 Zerf, Germany. Tel. ++49 (0)6587 1025; E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Milen Marinov, 7/160 Rossall Str., Merivale 8014, Christchurch, New Zealand. E-mail: [email protected] Published in Rheinfelden, Germany and printed in Trier, Germany. ISSN 1438-0269 years old) than old beaver ponds. These studies have 1997 concluded, based on waterfowl use only, that new bea- ver ponds are more productive for waterfowl than old 11030. Prejs, A.; Koperski, P.; Prejs, K. (1997): Food- beaver ponds. I tested the hypothesis that productivity web manipulation in a small, eutrophic Lake Wirbel, Po- in beaver ponds, in terms of macroinvertebrates and land: the effect of replacement of key predators on epi- water quality, declined with beaver pond succession. In phytic fauna. Hydrobiologia 342: 377-381. (in English) 1993 and 1994, fifteen and nine beaver ponds, respec- ["The effect of fish removal on the invertebrate fauna tively, of three different age groups (new, mid-aged, old) associated with Stratiotes aloides was studied in a shal- were sampled for invertebrates and water quality to low, eutrophic lake. The biomass of invertebrate preda- quantify differences among age groups. No significant tors was approximately 2.5 times higher in the inverte- differences (p < 0.05) were found in invertebrates or brate dominated year (1992) than in the fish-dominated water quality among different age classes. -

Odonata: Zygoptera) Focusing on Functional Aspects of the Mouthparts Sebastian Büsse1* , Thomas Hörnschemeyer2 and Stanislav N

Büsse et al. Frontiers in Zoology (2017) 14:25 DOI 10.1186/s12983-017-0209-x RESEARCH Open Access The head morphology of Pyrrhosoma nymphula larvae (Odonata: Zygoptera) focusing on functional aspects of the mouthparts Sebastian Büsse1* , Thomas Hörnschemeyer2 and Stanislav N. Gorb1 Abstract Background: The understanding of concerted movements and its underlying biomechanics is often complex and elusive. Functional principles and hypothetical functions of these complex movements can provide a solid basis for biomechanical experiments and modelling. Here a description of the cephalic anatomy of Pyrrhosoma nymphula (Zygoptera, Coenagrionidae) focusing on functional aspects of the mouthparts using micro computed tomography (μCT) is presented. Results: We compared six different instars of the damselfly P. nymphula as well as one instar of the dragonfly Aeshna cyanea and Epiophlebia superstes each. In total 42 head muscles were described with only minor differences of the attachment points between the examined species and the absence of antennal muscle M. scapopedicellaris medialis (0an7) in Epiophlebia as a probable apomorphy of this group. Furthermore, the ontogenetic differences between the six larval instars are minor; the only considerable finding is the change of M. submentopraementalis (0la8), which is dichotomous in the early instars (I1,I2 and I3) with a second point of origin at the postero-lateral base of the submentum. This dichotomy is not present in any of the older instars studied (I6, middle-late and pen-ultimate). Conclusion: However, the main focus of the study herein, is to use these detailed morphological descriptions as basis for hypothetic functional models of the odonatan mouthparts. We present blueprint like description of the mouthparts and their musculature, highlighting the caused direction of motion for every single muscle. -

In Bhutan, Biology, Ecology, Distribution

Odonatologica38(3): 203-215 SeptemberI, 2009 New records of Epiophlebialaidlawi Tillyard in Bhutan, with notes on its biology, ecology, distribution, zoogeographyand threat status (Anisozygoptera: Epiophlebiidae)* ¹ ² T. Brockhaus and A. Hartmann 1 An der Morgensonne 5 D-09387 Jahnsdorf/Erzgebirge, Germany [email protected] 2 Universitat fur Bodenkultur Wien, Institut fin Hydrobiologie& Gewassermanagement, Max - Emanuelstrasse 17, A-l 180 Wien, Austria [email protected],at Received December 21, 2008 /Revised and AcceptedMarch 15, 2009 E. laidlawi larvae were found for the first time in Bhutan, collected in 5 streams in and central W parts of the country, at altitudes 2350-2885 m a.s.l. The habitats and larval developmentstages are described, and a brief overview is presented on the bi- ology, ecology and known distribution in India and The inhabits Bhutan, Nepal. sp. fast running mountain streams in Himalayan broadleaf and subtropical pine forests at an altitude of 1300-2885 m a.s.1. The palaeobiogeographicalhistory of the fossil and Stenophlebiidaeand of the 2 extant is discussed. Epiophlebiidae Epiophlebiaspp. E. laidlawi is relict in headwaters of mountain forests. is endan- a sp., living pristine It because of human such of gered influences, as deforestation,provision water power, erosion and other factors. The best protection would be ensured by the conservation of vast specific habitats in protected areas. This has at least partly been put into ac- tion in Nepal. INTRODUCTION laidlawi Epiophlebia Tillyard, 1921 was described controversially from a larva foundin and the adult found 1918, was only 45 years later;even now much remains be discoveredabout this to poorly understood species, described as the “old vet- eran”, the “old relict” (DAVIS 1992), and the “living ghost” (MAHATO, 1993). -

Evolution, Taxonomy, Libelluloides

Odonalologica24(4): 383-424 December I. 1995 Evolution, taxonomy, and biogeography ofancient Gondwanianlibelluloides, with comments on anisopteroidevolution and phylogenetic systematics (Anisoptera: Libelluloidea)* F.L. Carle¹ Department of Entomology,Cook College, New Jersey Agricultural ExperimentStation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08903, United States Received October 14, 1994 / Reviewed and Accepted April 4, 1995 /Final additions and modificatons received May 17, 1995 New phylogenetic systematic methodologies are presented and the terms ‘neapomorphy’, ‘coapomorphy’, ‘exapomorphy’ and ‘apophyletic’ introduced. Re- sults are presented in sorted character state matrices which show the outcome of char- acter state evaluation while depicting phylogenetic arrangement. Higher classifica- tion, phylogeny, and biogeography of Anisoptera are reviewed and keys provided for superfamilies and families. The pattern of anisopteroid neapomorphy supports the superfamily arrangement proposed by F.L. CARLE (1986, Odonatologica 15: 275- -326), whileindicatingpolyphyly for Cordulegasteroidea[sic] ofEC. FRASER (1957, A reclassification of the order Odonata, R. Zool. Soc NSW, Sydney) and both “Neanisoptera”and“Petaluroidea”ofH.-K.PFAU (1991, Adv. Odonalol. 5: 109-141). Paraphyletic groupingsinclude Aeschnidae [sic] of R.J. TILLYARD (1917, The biol- D. DAY1ES ogy of dragonflies,Cambridge Univ. Press), and Cordulegastroideaof A.L. int. Nothomacromia (1981, Soc. odonatol. rapid Comm. 3: 1-60). nom.n.is proposed as areplacement for Pseudomacromia Carle & Wighton, 1990,nec. Pseudomacromia Kirby, 1890. Congruence between phylogenetic and biogeographicpatterns indicates two or more distinct mesozoic utilizations of a trans-pangaeian montane dispersal Incorrect association of with for the 137 route. Neopetalia austropetaliids past years has obscured the gondwanianorigin and subsequent radiation of non-cordulegastrid which least 140 million the frozen Libelluloidea,a process began at years ago on now continent of Antarctica.