Genesis 1 As Vision: What Are the Implications?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rede Record Brazil's 'Os Dez Mandamentos': You Still Haven't Seen It All

Rede Record Brazil's 'Os Dez Mandamentos': You Still Haven't Seen It All 04.04.2016 Regarded as the great sensation of Brazilian television, the biblical telenovela Os Dez Mandamentos (The Ten Commandments), returns for a second season, with a warning: you still haven't seen it all. The series, penned by Vivian de Oliveira, will premiere Monday, April 4, at 8:30 p.m. on Rede Record Brazil. The channel - considered Brazil's second-largest producer of original content with a total of more than 90 hours per week - offers programming focused on the Brazilian family. The novela's first season was exported to Argentina, where it aired on Telefe in prime time, becoming the country's most-watched program in its debut, scoring a 14.9 household ratings average. Also, the production has been turned into a film, where it became the second biggest box-office hit in the history of Brazilian cinema. The launch campaign for the show's second season builds on this phenomenon. "The great secret behind the excellent results obtained by The Ten Commandments has been selling the product as a telenovela, and not as a biblical story," says Alexandre Barbosa Machado de Souza, on-air creative promos coordinator for Rede Record. This is why since season one the communication strategy has focused "more on the plot than the biblical aspects, including the romances, the conflicts, the betrayals and the drama that all major soap operas have," Souza says. As for the show's Biblical origins, Marcelo Caetano, programming director of Rede Record, says "we have been producing this type of content since 2010. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

The Life of Moses #25 February 2, 2020

The Life of Moses #25 February 2, 2020 “The 10 Plagues upon Egypt” Part 5 Exodus 7-12 Introduction: Tonight, we return to the first of the ten plagues which God brought upon Egypt. This plague consisted of the water being turned into blood. This beginning of plagues would have been devastating to the Egyptians. The Nile River was the lifeline which flowed through the land. Let me review the points which we looked at last week. 1. The Reproving before the Plague Notice Exodus 7:14-16 Pharaoh was given fair warning before the plague. We considered this thought before, but I will remind you again that God always brings a warning before His judgment falls. 2. The Revelation in the Plague Notice Exodus 7:17 One of the purposes of all the plagues would be to educate the people of Egypt and Israel about God. 3. The Ruin of the Plague. Notice Exodus 7:19-21 This plague was devasting to the Egyptians. The river waters and the ponds were all turned to blood. It would affect three areas of their lives: 1. Their food supplies. 2. Their environment. 3. Their economy. Egypt was desert country. They depended completely upon the Nile for irrigation as well as soil to put upon their fields. Most of Egypt’s trade and commerce depended upon the Nile River. This plague was a great blow to every area in Egypt. 4. The Reaping of the Plague. This plague of water to blood brought upon Egypt was the reaping of that which they were guilty of in the past. -

Of the Bible, 1830-1833: Doctrinal Development During the Kirtland Era

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 11 Issue 4 Article 6 10-1-1971 The “New Translation” of the Bible, 1830-1833: Doctrinal Development During the Kirtland Era Robert J. Matthews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Matthews, Robert J. (1971) "The “New Translation” of the Bible, 1830-1833: Doctrinal Development During the Kirtland Era," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 11 : Iss. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol11/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Matthews: The “New Translation” of the Bible, 1830-1833: Doctrinal Develop the new translation of the bible 183018331830 1833 doctrinal development during the kirtland era ROBERT j MATTHEWS before one can recognize the role of the new transla- tion 1 of the bible in the development of doctrine during the kirtland era of church history it is necessary that he first have a historical perspective of the beliefs and practices of the church at various times since its organization in 1830 in addi- tion it is necessary that one know what the new translation of the bible is why the prophet joseph smith made the transla- tion when it was made and how it was made in pursuit of these items this article will attempt to look at the church in the early 1830s and -

Ponder the New Proclamation.Pdf

Ponder THE NEWProclamation A 9-WEEK COUNTDOWN TO GENERAL CONFERENCE FIND THE LINKS TO TALKS & VIDEOS AT LDSLIVING.COM/PROCLAMATION AUGUST 2–8 We solemnly proclaim that God loves His children in every nation of the world. God the Father has given us the divine birth, the incomparable life, and the infinite atoning sacrifice of His Beloved Son, Jesus Christ. By the power of the Father, Jesus rose again and gained the victory over death. He is our Savior, our Exemplar, and our Redeemer. SUNDAY SCRIPTURE: Read and ponder John 3:16–17. MONDAY MOVIE: Watch “God Loves His Children | Now You Know.” TUESDAY TALK: :Study Elder Gerrit W. Gong’s talk, “Hosanna and Hallelujah—The Living Jesus Christ The Heart of Restoration and Easter.” WEDNESDAY WORSHIP: Listen to Calee Reed and Stephen Nelson perform “This Is the Christ.” THURSDAY TIME TO MEMORIZE: Take some time to memorize this week’s paragraph. Fill-in-the-blank guides and tips can be found at ldsliving.com/proclamation. FRIDAY FEELINGS: Record what it means to you that Christ is your Savior, Exemplar, and Redeemer. SATURDAY SHARE: Share your testimony of Jesus Christ with a loved one. AUGUST 9–15 Two hundred years ago, on a beautiful spring morning in 1820, young Joseph Smith, seeking to know which church to join, went into the woods to pray near his home in upstate New York, USA. He had questions regarding the salvation of his soul and trusted that God would direct him. SUNDAY SCRIPTURE: Read and ponder Joseph Smith—History 1:5–14. MONDAY MOVIE: Watch “The Hope of God’s Light.” TUESDAY TALK: Study President Henry B. -

1. the Account of Korah and His Followers Numbers 16:1-40 We Read the Account in Our First Two Lenten Thoughts On… Rebellion Scripture Readings This Morning

Holy Trinity Lutheran Church centuries ago. And then we will learn lessons Des Moines, WA for our faith and our Christian life as we worship God this Lent. March 3, 2013 1. The account of Korah and his followers Numbers 16:1-40 We read the account in our first two Lenten Thoughts on… Rebellion Scripture readings this morning. Background 1. The account of Korah and his information will be very helpful to us in followers understanding what exactly was happening in that power struggle. Looking back, the 2. Lenten lessons for our faith and life Israelites had left Egypt in a dramatic exodus. Moses had led them through the parted Red Sea and Pharaoh’s army had been dashed to Hymns: 385 – 302 – Distribution: 116, 124 – pieces behind them. Then the community of Closing: 114 (6-7) Israel had journeyed through the wilderness to Mt. Sinai, where they had paused for quite a All Scripture quotations from NIV 1984 while as Moses received the laws of God on the mountain. Then they had traveled northward all the way to the southern border of the Power struggles! They are common in our Promised Land. Spies had been sent to check world today: out Canaan and had returned with a negative • Nations struggle for power. We watch report: “We can’t take this land! The cities are on news channels as nations undergo too fortified and the people are too strong!” riots and depose their governmental Therefore, in Numbers 14 God declared that leaders. due to their lack of faith and their complaint • Our own Congress struggles for power. -

Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2021 "He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 Steven R. Hepworth Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hepworth, Steven R., ""He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8062. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8062 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "HE BEHELD THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS": JOSEPH SMITH AND DIABOLISM IN EARLY MORMONISM 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: Patrick Mason, Ph.D. Kyle Bulthuis, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Harrison Kleiner, Ph.D. D. Richard Cutler, Ph.D. Committee Member Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Steven R. Hepworth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “He Beheld the Prince of Darkness”: Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2021 Major Professor: Dr. Patrick Mason Department: History Joseph Smith published his first known recorded history in the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. -

Moses and Miriam Praise God

Moses and Miriam Praise God Bible Background • EXODUS 14:1–15:1-21 Printed Text • EXODUS 15:11–21 | Devotional Reading • PSALM 105:1–2, 37–45 Aim for Change By the end of this lesson, we will EXPLORE why and how Moses and Miriam praised God; REFLECT on the actions of God that are celebrated through music, dance, and words; and CELEBRATE God’s faithfulness with joy. In Focus “FIRE DEPARTMENT, CALL OUT!” “Over here!” Ramona cried, coughing. The smoke stung her eyes and was so thick that she couldn’t see where the voice was coming from. The disaster had been sudden. One moment, she was typing away at her desk. The next, there was a quick rumble from the ground that shook the floor and shattered the floor-to-ceiling windows. Part of the ceiling frame fell to the floor, dragging down tiles and light fixtures. Some of the sprinklers came on and drenched everything nearby, but others were broken. The way to the exit stairs was blocked with flaming debris. Ramona prayed, “Heavenly Father, please bring me to safety.” She could hear the firefighters crashing through the wreckage to get to her. “OVER HERE!” she shouted again. Ramona could see the shapes of the firefighters coming forward in the dark, knocking aside desks and chairs and filing cabinets. The water sprayed from their hoses sizzled and turned to steam as it hit the flames, adding to the chaotic scene. But after a moment, two of them emerged like ghosts and crouched next to her. “Praise God! I am so grateful to see you!” Ramona cried. -

Hard Questions and Keeping the Faith

HARD QUESTIONS AND KEEPING THE FAITH by Michael R. Ash As Bill prepared an Elder’s Quorum lesson, he vaguely While the foregoing story is fictional, it is nonetheless recalled a quote from a past general conference, which, he similar to the experience of at least a few members of the thought, would enhance his lesson. Not remembering the Church. Since Joseph Smith’s First Vision, there have been exact quote, nor even who said it and when, Bill turned some who have made it their goal to revile his name his to the Internet and entered a search with a couple of key work, and his legacy. And since before the Book of Mor- words and the word “Mormon.” Bill perused the various mon came from the printing press, there have been critics “hits” returned by the search engine and found that some of who have denounced it as fictional, delusional, or blasphe- the Web pages were hostile to the Church. Initially he sim- mous. Why do some people assail the Church? Should we ply ignored these pages and continued searching through respond to critics? How should we deal with hard ques- faithful Web sites. At times, however, he found it diffi- tions and accusations? Were can we find answers? cult—upon an initial glance—to distinguish some hostile Web sites versus faithful Web sites. Some hostile sites ap- peared harmless until he read a little further. One site in WHY DO SOME PEOPLE ASSAIL THE CHURCH? particular caught his attention and he began to read more During Moroni’s initial visit with Joseph, the angel told and more of the claims made by the Web site’s author. -

Finding God in the Book of Moses

Finding God in The Book of Moses Santa Barbara Community Church Winter / Spring Calendar 2007 Teaching Study Text Title Date 1/28 1 Genesis 1:1-2:3 Finding God in the Beginning 2/4 2 Genesis 2-3 In the Garden: God Betrayed 2/11 3 Genesis 11:27— Calling a Chaldean: God’s Promise 12:9 2/18 4 Genesis 21—22 A Son Called Laughter: God Provides 2/25 5 Genesis 16; Hagar and Ishmael: God Hears 21:8-21 3/4 6 Genesis 25:19- Jacob’s Blessing: God Chooses 34; 26:34—28:5 3/11 7 Genesis 42—47 Joseph: God Plans 3/18 8 Exodus 1-2 Moses: God Knows 3/25 9 Exodus 11-12 Passover: God Delivers 4/1 10 Exodus 19 Smoke on the Mountain: God Unapproachable 4/8 11 Exodus 20:1-21 The Ten Words: God Wills 4/15 Easter 4/22 12 Exodus 24:15— The Tent: God Dwells 27:19 4/29 Retreat Sunday The text of this study was written and prepared by Reed Jolley. Thanks to DeeDee Underwood, Erin Patterson, Bonnie Fear and Susi Lamoutte for proof reading the study. And thanks to Kat McLean (cover and studies 1,4,8, 11), Kaitee Hering (studies 3,5,7,10), and Paul Benthin (studies 2,6,9,12) for providing the illustrations. All Scripture citations unless otherwise noted are from the English Standard Version. May God bless Santa Barbara Community Church as we study his word! SOURCES/ABBREVIATIONS Childs Brevard Childs. The Book of Exodus: A Critical, Theological Commentary, Westminster, 1967 Cole R. -

Integrating Textual Criticism in the Study of Early Mormon Texts and History

Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies Volume 10 Number 1 Fall 2019 Article 6 2019 Returning to the Sources: Integrating Textual Criticism in the Study of Early Mormon Texts and History Colby Townsend Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal Recommended Citation Townsend, Colby "Returning to the Sources: Integrating Textual Criticism in the Study of Early Mormon Texts and History." Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 10, no. 1 (2019): 58-85. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol10/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWNSEND: RETURNING TO THE SOURCES 1 Colby Townsend {[email protected]} is currently applying to PhD programs in early American literature and religion. He completed an MA in History at Utah State University under the direction of Dr. Philip Barlow. He previously received two HBA degrees at the University of Utah in 2016, one in compartibe Literary and Culture Studies with an emphasis in religion and culture, and the other in Religious Studies—of the latter, his thesis was awarded the marriot Library Honors Thesis Award and is being revised for publication, Eden in the Book of Mormon: Appropriation and Retelling of Genesis 2-4 (Kofford, forthcoming). 59 INTERMOUNTAIN WEST JOURNAL OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES Colby Townsend† Returning to the Sources: Integrating Textual Criticism in the Study of Early Mormon Texts and History As historians engage with literary texts, they should ask a few important questions. -

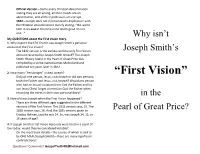

Joseph Smith's First Vision.Pdf

Official Version—Slams every Christian denomination stating they are all wrong, all their creeds are an abomination, and all their professors are corrupt. 1832—Joseph does not mention God’s displeasure with the Christian denominations merely stating, “the world lieth in sin and at this time none doeth good no not one...” Why isn’t My QUESTIONS about the First Vision Story: 1. Why doesn’t the LDS Church use Joseph Smith’s personal account of the First Vision? The 1832 version is the earliest and the only First Vision Joseph Smith’s account recorded by Joseph Smith himself? The Joseph Smith History found in the Pearl of Great Price was compiled by a scribe named James Mulholland and published ten years later in 1842. 2. How many “Personages” visited Joseph? “First Vision” Did just one person, Jesus, visit Joseph or did two persons, both the Father and Jesus, visit Joseph? Would any person who had an actual visitation from God the Father and his son Jesus Christ forget to mention God the Father when recording the event in their own personal diary? in the 3. How old was Joseph when the First Vision happened? There are three different ages suggested in the different versions of the First Vision. The 1832 version says, 15. The 1838 version says, 16. And, the 1835 version, given to Pearl of Great Price? Erastus Holmes, says he was 14. So, was Joseph 14, 15, or 16 years of age? 4. If Joseph Smith’s First Vision Accounts were tried in a court of law today, would they be considered reliable? On the most basic details—the source of which is said