Writing History Must Not Be an Act of “Magic”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moroni: Angel Or Treasure Guardian? 39

Mark Ashurst-McGee: Moroni: Angel or Treasure Guardian? 39 Moroni: Angel or Treasure Guardian? Mark Ashurst-McGee Over the last two decades, historians have reconsidered the origins of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the context of the early American tradition of treasure hunting. Well into the nineteenth century there were European Americans hunting for buried wealth. Some believed in treasures that were protected by magic spells or guarded by preternatural beings. Joseph Smith, founding prophet of the Church, had participated in several treasure-hunting expeditions in his youth. The church that he later founded rested to a great degree on his claim that an angel named Moroni had appeared to him in 1823 and showed him the location of an ancient scriptural record akin to the Bible, which was inscribed on metal tablets that looked like gold. After four years, Moroni allowed Smith to recover these “golden plates” and translate their characters into English. It was from Smith’s published translation—the Book of Mormon—that members of the fledgling church became known as “Mormons.” For historians of Mormonism who have treated the golden plates as treasure, Moroni has become a treasure guardian. In this essay, I argue for the historical validity of the traditional understanding of Moroni as an angel. In May of 1985, a letter to the editor of the Salt Lake Tribune posed this question: “In keeping with the true spirit (no pun intended) of historical facts, should not the angel Moroni atop the Mormon Temple be replaced with a white salamander?”1 Of course, the pun was intended. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Ponder the New Proclamation.Pdf

Ponder THE NEWProclamation A 9-WEEK COUNTDOWN TO GENERAL CONFERENCE FIND THE LINKS TO TALKS & VIDEOS AT LDSLIVING.COM/PROCLAMATION AUGUST 2–8 We solemnly proclaim that God loves His children in every nation of the world. God the Father has given us the divine birth, the incomparable life, and the infinite atoning sacrifice of His Beloved Son, Jesus Christ. By the power of the Father, Jesus rose again and gained the victory over death. He is our Savior, our Exemplar, and our Redeemer. SUNDAY SCRIPTURE: Read and ponder John 3:16–17. MONDAY MOVIE: Watch “God Loves His Children | Now You Know.” TUESDAY TALK: :Study Elder Gerrit W. Gong’s talk, “Hosanna and Hallelujah—The Living Jesus Christ The Heart of Restoration and Easter.” WEDNESDAY WORSHIP: Listen to Calee Reed and Stephen Nelson perform “This Is the Christ.” THURSDAY TIME TO MEMORIZE: Take some time to memorize this week’s paragraph. Fill-in-the-blank guides and tips can be found at ldsliving.com/proclamation. FRIDAY FEELINGS: Record what it means to you that Christ is your Savior, Exemplar, and Redeemer. SATURDAY SHARE: Share your testimony of Jesus Christ with a loved one. AUGUST 9–15 Two hundred years ago, on a beautiful spring morning in 1820, young Joseph Smith, seeking to know which church to join, went into the woods to pray near his home in upstate New York, USA. He had questions regarding the salvation of his soul and trusted that God would direct him. SUNDAY SCRIPTURE: Read and ponder Joseph Smith—History 1:5–14. MONDAY MOVIE: Watch “The Hope of God’s Light.” TUESDAY TALK: Study President Henry B. -

Claremont Mormon Studies J Newsletteri

Claremont Mormon Studies j NEWSLETTERi SPRING 2011 t IssUE NO . 4 A Claremont Sojourn IN THIS ISSUE BY Richard Bushman The End of Our Era PAGE 2 Howard W. Hunter Chair of Mormon Studies k laudia and I spent a year in Pas- enterprise. Mormon students iBlessed, Honored adena in 1997 and 1998 when I would comprise the bulk of the C Pioneers PAGE 2 started work on Joseph Smith: Rough seminar participants with a few Stone Rolling. At that time Interstate curious outsiders scattered in. The k 210 had not reached Claremont, and experiment has worked well. It Farewells to Richard and the town seemed a long way away. attracted a large group of inquisitive The last five miles or so on Foothill Latter-day Saints to the School of Claudia Bushman PAGES 2 & 3 Boulevard seemed to take forever. Religion. Claremont had always k Even so the beautiful campus made drawn Mormons but by this last the university alluring, a little aca- winter, Mormon students or non- Contributions to Mormon demic paradise well worth the trip. Mormons in the Mormon Studies Studies PAGE 4 Ten years later, when an offer came program constituted 20% of all k to teach here, it did not take much to active SOR students taking courses persuade us. or preparing for qualifying exams. Students Bid Farewell PAGE 7 We were drawn This core with their by the grand “The beautiful campus active program experiment Karen made the university of speakers and Torjesen and the alluring, a little conferences, and now The students had less of a School of Religion the institution of the problem adjusting to the academic were undertaking. -

Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2021 "He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 Steven R. Hepworth Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hepworth, Steven R., ""He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8062. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8062 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "HE BEHELD THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS": JOSEPH SMITH AND DIABOLISM IN EARLY MORMONISM 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: Patrick Mason, Ph.D. Kyle Bulthuis, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Harrison Kleiner, Ph.D. D. Richard Cutler, Ph.D. Committee Member Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Steven R. Hepworth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “He Beheld the Prince of Darkness”: Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2021 Major Professor: Dr. Patrick Mason Department: History Joseph Smith published his first known recorded history in the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. -

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 10 Issue 2

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 10 Number 2 Article 13 7-31-2001 Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 10 Issue 2 Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Scholarship, Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious (2001) "Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 10 Issue 2," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol10/iss2/13 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JOURNAL OF Book of Mormon Studies Volume 10 | Number 2 | 2001 More Altars from Nephi’s “Nahom” Two New Book of Mormon Hymns ! Brother Brigham on the Book of Mormon ! “Strait” or “Straight”? ! Serpents Both Good and Evil ! Terryl Givens on Revelation ! More Light on Who Wrote the Title Page 6 16 28 34 42 56 On the cover: Votive altars at the Bar<an temple complex and inscribed wall at the Awwam temple. Both sites are located near Marib, Yemen. Photography by Warren P. Aston. CONTENTS 2 Contributors 3 The Editor’s Notebook 4 A New Editorial Team Feature Articles 6 Brigham Young and the Book of Mormon w. jeffrey marsh Brother Brigham, as we would expect for a person of his era and background, depended heavily on the Bible, but he found con- tinual support in the Book of Mormon for his understanding of the gospel. -

Hard Questions and Keeping the Faith

HARD QUESTIONS AND KEEPING THE FAITH by Michael R. Ash As Bill prepared an Elder’s Quorum lesson, he vaguely While the foregoing story is fictional, it is nonetheless recalled a quote from a past general conference, which, he similar to the experience of at least a few members of the thought, would enhance his lesson. Not remembering the Church. Since Joseph Smith’s First Vision, there have been exact quote, nor even who said it and when, Bill turned some who have made it their goal to revile his name his to the Internet and entered a search with a couple of key work, and his legacy. And since before the Book of Mor- words and the word “Mormon.” Bill perused the various mon came from the printing press, there have been critics “hits” returned by the search engine and found that some of who have denounced it as fictional, delusional, or blasphe- the Web pages were hostile to the Church. Initially he sim- mous. Why do some people assail the Church? Should we ply ignored these pages and continued searching through respond to critics? How should we deal with hard ques- faithful Web sites. At times, however, he found it diffi- tions and accusations? Were can we find answers? cult—upon an initial glance—to distinguish some hostile Web sites versus faithful Web sites. Some hostile sites ap- peared harmless until he read a little further. One site in WHY DO SOME PEOPLE ASSAIL THE CHURCH? particular caught his attention and he began to read more During Moroni’s initial visit with Joseph, the angel told and more of the claims made by the Web site’s author. -

Integrating Textual Criticism in the Study of Early Mormon Texts and History

Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies Volume 10 Number 1 Fall 2019 Article 6 2019 Returning to the Sources: Integrating Textual Criticism in the Study of Early Mormon Texts and History Colby Townsend Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal Recommended Citation Townsend, Colby "Returning to the Sources: Integrating Textual Criticism in the Study of Early Mormon Texts and History." Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 10, no. 1 (2019): 58-85. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol10/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWNSEND: RETURNING TO THE SOURCES 1 Colby Townsend {[email protected]} is currently applying to PhD programs in early American literature and religion. He completed an MA in History at Utah State University under the direction of Dr. Philip Barlow. He previously received two HBA degrees at the University of Utah in 2016, one in compartibe Literary and Culture Studies with an emphasis in religion and culture, and the other in Religious Studies—of the latter, his thesis was awarded the marriot Library Honors Thesis Award and is being revised for publication, Eden in the Book of Mormon: Appropriation and Retelling of Genesis 2-4 (Kofford, forthcoming). 59 INTERMOUNTAIN WEST JOURNAL OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES Colby Townsend† Returning to the Sources: Integrating Textual Criticism in the Study of Early Mormon Texts and History As historians engage with literary texts, they should ask a few important questions. -

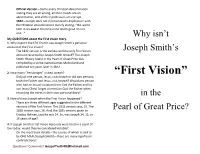

Joseph Smith's First Vision.Pdf

Official Version—Slams every Christian denomination stating they are all wrong, all their creeds are an abomination, and all their professors are corrupt. 1832—Joseph does not mention God’s displeasure with the Christian denominations merely stating, “the world lieth in sin and at this time none doeth good no not one...” Why isn’t My QUESTIONS about the First Vision Story: 1. Why doesn’t the LDS Church use Joseph Smith’s personal account of the First Vision? The 1832 version is the earliest and the only First Vision Joseph Smith’s account recorded by Joseph Smith himself? The Joseph Smith History found in the Pearl of Great Price was compiled by a scribe named James Mulholland and published ten years later in 1842. 2. How many “Personages” visited Joseph? “First Vision” Did just one person, Jesus, visit Joseph or did two persons, both the Father and Jesus, visit Joseph? Would any person who had an actual visitation from God the Father and his son Jesus Christ forget to mention God the Father when recording the event in their own personal diary? in the 3. How old was Joseph when the First Vision happened? There are three different ages suggested in the different versions of the First Vision. The 1832 version says, 15. The 1838 version says, 16. And, the 1835 version, given to Pearl of Great Price? Erastus Holmes, says he was 14. So, was Joseph 14, 15, or 16 years of age? 4. If Joseph Smith’s First Vision Accounts were tried in a court of law today, would they be considered reliable? On the most basic details—the source of which is said -

The First Vision: Key to Truth

By Elder Richard J. Maynes Of the Presidency of the Seventy The First Vision KEY TO TRUTH Let us not forget or take for granted the many precious truths we have learned from Joseph Smith’s First Vision. he Restoration of the fulness began in the United States. These reviv- of the gospel of Jesus Christ als are known by historians as part of in the latter days was foreseen the Second Great Awakening. It was Tand predicted by prophets through- through these revival meetings’ com- out history. The Restoration, therefore, peting notions of salvation that Joseph should not come as a surprise to those Smith and his family navigated their who study the scriptures. Dozens of religious commitment. prophetic statements throughout the Joseph was greatly influenced by Old Testament, the New Testament, and the teachings and discussions of his the Book of Mormon clearly predict father, who searched for but could not and point toward the Restoration of find among the revivalist sects any that the gospel.1 were organized like the ancient order BY WALTER RANE BY WALTER In the late 1790s, approximately of Jesus Christ and His Apostles. Joseph 2,400 years after King Nebuchadnezzar would listen and ponder during family saw in a dream that “the God of heaven Bible study. By the age of 12, he began [shall] set up a kingdom, which shall to worry about his sins and the welfare never be destroyed” (Daniel 2:44), a of his immortal soul, which led him to JOSEPH SMITH WITH FATHER AND SON, JOSEPH SMITH WITH FATHER decades-long series of religious revivals search the scriptures for himself. -

Joseph Smith and the Structure of Mormon Identity

JOSEPH SMITH AND THE STRUCTURE OF MORMON IDENTITY STEVEN L. OLSEN IN 1838, JOSEPH SMITH reduced to written form the sacred experience which led him to establish Mormonism.1 This narrative relates a series of heavenly visitations which Smith said had begun eighteen years earlier and had con- tinued until 1829. Although Smith drafted earlier and later accounts of these events, only the 1838 version has been officially recognized by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Smith commenced his official History of the Church with this narrative. It also appeared in an 1851 collection of sacred and inspirational writings published by the Church in the British Isles. The permanent status of this text in Mormonism was secured in 1880 by its canonization at the hand of John Taylor who had recently succeeded Brigham Young to the Mormon Presidency. Since its canonization, the "Joseph Smith story," as it is known among Mormons, has become a primary document for the explication of Mormon doctrine and the introduction for many proselytes to the Church. The text has come to demand the loyalty of orthodox Mormons and has become one of Mormonism's most sacred texts. Remarkable is the contrast between the official status of the 1838 version and the general neglect by the Church of the other accounts. This difference in status cannot be explained by the historical accuracy of the respective accounts. Despite some serious challenges to the chronology of the official account, Mormons have firmly defended its historicity, even though several of the non-canonized versions do not suffer from these perceived historical inaccuracies.2 Neither can this distinction be demonstrated by the degree of complementarity of the different versions. -

On Saving the Constitution Or Why Some Utah Mormons Should Become Democrats

May 1988 Volume 12:3 Issue 65 2 Our Readers ..................... READERS FORUM FEATURES 8 Chauncey C. Riddle ............... WHAT A PRIVILEGE TO BELIEVE! A philosopher explores the pillars of his faith 12 JulieJ. Nichols ................... PENNYROYAL COHOSH, RUE 1987 D.K. Brown Fiction Contest Winner 17 Richard D. Poll ................... DEALING WITH DISSONANCE." MYTHS, DOCUME.NTS, AND FAITH The dynamic of keeping our faith-promoting stories honest 22 Eugene England .................. ON SAVING THE CONSTITUTION, OR WHY SUNSTONE (ISSN 0363-1370) is published by the SOME UTAH MORMONS SHOULD BECOME Sunstone Foundation, a non-profit corporation DEMOCRATS with no official connection to The Church of Jesus Maintaining our political balance Christ of Latter-day Saints. Articles represent the attitudes of the writers only and not necessarily COLUMNS those of the editors or the LDS church. 5 Elbert Eugene Peck ................ FROM THE EDITOR Engaging Studene~ in the Church’s Foyer Manuscripts should be submitted on floppy dis- 6 Ronald G. Kershaw ................ TURNING THE TIME OVER TO .... kettes, IBM PC compatible and written with Word AIDS, Leprosy, and Disease: The Christian Perfect format. Manuscripts may also be double- Response spaced typewritten and should be submitted in duplicate. Submissions should not exceed six 31 Donce Williams Elliott ............. BETWEEN THE LINES thousand words. Unsolicited manuscripts will not Cultural iDogmas vs. Universal Truths be returned; authors will be notified concerning 33 James M. Hill .................... LIGHTER MINDS acceptance within sixty days. SUNSTONE is Richard L. Popp Toward A Mormon Cuisine: A Light-hearted interested in feature and column length articles Inquiry into the Cultural Significance of Food relevant to Mormonism from a variety of perspec- tives; news stories about Mormons and the LDS REVIEWS church are also desired.