The Federalist Society Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Meaning of the Constitution's Postal Clause

Birmingham City School of Law British Journal of British Journal of American Legal Studies | Volume 7 Issue 1 7 Issue Legal Studies | Volume British Journal of American American Legal Studies Volume 7 Issue 1 Spring 2018 ARTICLES Founding-Era Socialism: The Original Meaning of the Constitution’s Postal Clause Robert G. Natelson Toward Natural Born Derivative Citizenship John Vlahoplus Felix Frankfurter and the Law Thomas Halper Fundamental Rights in Early American Case Law: 1789-1859 Nicholas P. Zinos The Holmes Truth: Toward a Pragmatic, Holmes-Influenced Conceptualization of the Nature of Truth Jared Schroeder Acts of State, State Immunity, and Judicial Review in the United States Zia Akthar ISSN 2049-4092 (Print) British Journal of American Legal Studies Editor-in-Chief: Dr Anne Richardson Oakes, Birmingham City University. Associate Editors Dr. Sarah Cooper, Birmingham City University. Dr. Haydn Davies, Birmingham City University. Prof. Julian Killingley, Birmingham City University. Prof. Jon Yorke, Birmingham City University. Seth Barrett Tillman, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. Birmingham City University Student Editorial Assistants 2017-2018 Mercedes Cooling Graduate Editorial Assistants 2017-2018 Amna Nazir Alice Storey Editorial Board Hon. Joseph A. Greenaway Jr., Circuit Judge 3rd Circuit, U.S. Court of Appeals. Hon. Raymond J. McKoski, Circuit Judge (retired), 19th Judicial Circuit Court, IL. Adjunct Professor of Law, The John Marshall Law School, Chicago, IL. Prof. Antonio Aunion, University of Castille-la Mancha. Prof. Francine Banner, Phoenix School of Law, AZ. Prof. Devon W. Carbado, UCLA, CA. Dr. Damian Carney, University of Portsmouth, UK. Dr. Simon Cooper, Reader in Property Law, Oxford Brookes University. Prof. -

Patrick Henry

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY PATRICK HENRY: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HARMONIZED RELIGIOUS TENSIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY BY KATIE MARGUERITE KITCHENS LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA APRIL 1, 2010 Patrick Henry: The Significance of Harmonized Religious Tensions By Katie Marguerite Kitchens, MA Liberty University, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Samuel Smith This study explores the complex religious influences shaping Patrick Henry’s belief system. It is common knowledge that he was an Anglican, yet friendly and cooperative with Virginia Presbyterians. However, historians have yet to go beyond those general categories to the specific strains of Presbyterianism and Anglicanism which Henry uniquely harmonized into a unified belief system. Henry displayed a moderate, Latitudinarian, type of Anglicanism. Unlike many other Founders, his experiences with a specific strain of Presbyterianism confirmed and cooperated with these Anglican commitments. His Presbyterian influences could also be described as moderate, and latitudinarian in a more general sense. These religious strains worked to build a distinct religious outlook characterized by a respect for legitimate authority, whether civil, social, or religious. This study goes further to show the relevance of this distinct religious outlook for understanding Henry’s political stances. Henry’s sometimes seemingly erratic political principles cannot be understood in isolation from the wider context of his religious background. Uniquely harmonized -

Virginia Historical Society the CENTER for VIRGINIA HISTORY

Virginia Historical Society THE CENTER FOR VIRGINIA HISTORY ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2004 ANNUAL MEETING, 23 APRIL 2005 Annual Report for 2004 Introduction Charles F. Bryan, Jr. President and Chief Executive Officer he most notable public event of 2004 for the Virginia Historical Society was undoubtedly the groundbreaking ceremony on the first of TJuly for our building expansion. On that festive afternoon, we ushered in the latest chapter of growth and development for the VHS. By turning over a few shovelsful of earth, we began a construction project that will add much-needed programming, exhibition, and storage space to our Richmond headquarters. It was a grand occasion and a delight to see such a large crowd of friends and members come out to participate. The representative individuals who donned hard hats and wielded silver shovels for the formal ritual of begin- ning construction stood in for so many others who made the event possible. Indeed, if the groundbreaking was the most important public event of the year, it represented the culmination of a vast investment behind the scenes in forward thinking, planning, and financial commitment by members, staff, trustees, and friends. That effort will bear fruit in 2006 in a magnifi- cent new facility. To make it all happen, we directed much of our energy in 2004 to the 175th Anniversary Campaign–Home for History in order to reach the ambitious goal of $55 million. That effort is on track—and for that we can be grateful—but much work remains to be done. Moreover, we also need to continue to devote resources and talent to sustain the ongoing programs and activities of the VHS. -

Mail Fraud State Law and Post-Lopez Analysis George D

Cornell Law Review Volume 82 Article 1 Issue 2 January 1997 Should Federalism Shield Corruption?-Mail Fraud State Law and Post-Lopez Analysis George D. Brown Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation George D. Brown, Should Federalism Shield Corruption?-Mail Fraud State Law and Post-Lopez Analysis , 82 Cornell L. Rev. 225 (1997) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol82/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHOULD FEDERALISM SHIELD CORRUPTION?- MAIL FRAUD, STATE LAW AND POST-LOPEZ ANALYSIS George D. Brownt I. INTRODUCTION-PROTECTION THROUGH PROSECUTION? There is a view of state and local governments as ethically-chal- lenged backwaters,' veritable swamps of corruption in need of the ulti- mate federal tutelage: protection through prosecution. Whether or not the view is accurate, the prosecutions abound.2 Many metropoli- tan newspapers have chronicled the federal pursuit of errant state and local officials.3 The pursuit is certain to continue. In the post-Water- gate period, the Justice Department has made political corruption at all levels of government a top priority.4 A vigorous federal presence in t Professor of Law and Associate Dean, Boston College Law School. A.B. 1961, Harvard University, LL.B. 1965, Harvard Law School. Chairman, Massachusetts State Eth- ics Commission. -

FEDERALISM and INSURANCE REGULATION BASIC SOURCE MATERIALS © Copyright NAIC 1995 All Rights Reserved

FEDERALISM AND INSURANCE REGULATION BASIC SOURCE MATERIALS © Copyright NAIC 1995 All rights reserved. ISBN 0-89382-369-4 National Association of Insurance Commissioners Printed in the United States of America FEDERALISM AND INSURANCE REGULATION BASIC SOURCE MATERIALS by SPENCER L. KIMBALL Professor Emeritus of Law, University of Chicago Research Professor, University of Utah College of Law Of Counsel, Manatt, Phelps & Phillips Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. and BARBARA P. HEANEY Attorney at Law, Madison, WI Consulting Attorney on Insurance, Wisconsin Legislative Council, 1978-1994 Madison, Wisconsin Table of Contents Prefatory Note ............................................................................. ix I. Origins of Regulation .............................................................. 3 A. Special Charters .............................................................. :.3 Commentary ......................................................... 3 Chapter LXXX, LAws or COMMONWEALTH OF M~SSACH~SETTS, 1806--1809 .............................. 3 B. General Incorporation Statutes .......................................... 6 Commentary ......................................................... 6 MASSACHUSETTS ACTS AND RESOLVES 1845, Chapter 23 ........................................................ 7 C. Beginnings of Formal Insurance Regulation ....................... 7 Commentary ......................................................... 7 MASSACHUSETTS ACTS AND RESOLVES 1852, Chapter 231 ...................................................... -

Some Consequences of Increased Federal Activity in Law Enforcement David Fellman

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 2 1944 Some Consequences of Increased Federal Activity in Law Enforcement David Fellman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation David Fellman, Some Consequences of Increased Federal Activity in Law Enforcement, 35 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 16 (1944-1945) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. SOME CONSEQUENCES OF INCREASED FEDERAL ACTIVITY IN LAW ENFORCEIENT David Felhnan (The writer, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Nebraska, considers in this article the impact of our expanding national criminal jurisdiction upon American federalism, public law, constitutional morality, and standards of criminal justice.-EDrron.) The Growth of the Federal Criminal Code The First Congress, in its second session, adopted "An Act for the Punishment of certain Crimes against the United States."' It was a modest statute of thirty-three sections, dealing with treason, misprision of treason, felonies in places within the exclusive juris- diction of the United States and upon the high seas, forgery or counterfeiting of federal paper, the stealing or falsifying of rec- ords of the federal courts, perjury, bribery and obstruction of pro- cess in the courts, suits involving the public ministers of foreign states, and procedure. -

Patrick Henry, by Moses Coit Tyler 1

Patrick Henry, by Moses Coit Tyler 1 CHAPTER I CHAPTER II CHAPTER III CHAPTER IV CHAPTER V CHAPTER VI CHAPTER VII CHAPTER VIII CHAPTER IX CHAPTER X CHAPTER XI CHAPTER XII CHAPTER XIII CHAPTER XIV CHAPTER XV CHAPTER XVI CHAPTER XVII CHAPTER XVIII CHAPTER XIX CHAPTER XX CHAPTER XXI CHAPTER XXII Patrick Henry, by Moses Coit Tyler The Project Gutenberg eBook, Patrick Henry, by Moses Coit Tyler This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or Patrick Henry, by Moses Coit Tyler 2 online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Patrick Henry Author: Moses Coit Tyler Release Date: July 10, 2009 [eBook #29368] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PATRICK HENRY*** E-text prepared by Barbara Tozier, Bill Tozier, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) American Statesmen PATRICK HENRY by MOSES COIT TYLER Boston and New York Houghton Mifflin Company The Riverside Press Cambridge Copyright, 1887, by Moses Coit Tyler Copyright, 1898, by Moses Coit Tyler And Houghton, Mifflin & Co. Copyright, 1915, by Jeannette G. Tyler The Riverside Press Cambridge · Massachusetts Printed in the U.S.A. PREFACE In this book I have tried to embody the chief results derived from a study of all the materials known to me, in print and in manuscript, relating to Patrick Henry,--many of these materials being now used for the first time in any formal presentation of his life. -

A Computational Analysis of Constitutional Polarization

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2019 A Computational Analysis of Constitutional Polarization David E. Pozen Columbia Law School, [email protected] Eric L. Talley Columbia Law School, [email protected] Julian Nyarko Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation David E. Pozen, Eric L. Talley & Julian Nyarko, A Computational Analysis of Constitutional Polarization, CORNELL LAW REVIEW, VOL. 105, P. 1, 2019; COLUMBIA PUBLIC LAW RESEARCH PAPER NO. 14-624 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2271 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\C\CRN\105-1\CRN101.txt unknown Seq: 1 30-APR-20 8:10 A COMPUTATIONAL ANALYSIS OF CONSTITUTIONAL POLARIZATION David E. Pozen,† Eric L. Talley†† & Julian Nyarko††† This Article is the first to use computational methods to investigate the ideological and partisan structure of constitu- tional discourse outside the courts. We apply a range of ma- chine-learning and text-analysis techniques to a newly available data set comprising all remarks made on the U.S. House and Senate floors -

Documenting Women's Lives

Documenting Women’s Lives A Users Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A Acree, Sallie Ann, Scrapbook, 1868–1885. 1 volume. Mss5:7Ac764:1. Sallie Anne Acree (1837–1873) kept this scrapbook while living at Forest Home in Bedford County; it contains newspaper clippings on religion, female decorum, poetry, and a few Civil War stories. Adams Family Papers, 1672–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reel C321. This collection of consists primarily of correspondence, 1762–1788, of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), a merchant in Richmond, Va., and London, Eng., who served in the U.S. Continental Congress during the American Revolution and later settled in Augusta County. Letters chiefly concern politics and mercantile affairs, including one, 1788, from Martha Miller of Rockbridge County discussing horses and the payment Adams's debt to her (section 6). Additional information on the debt appears in a letter, 1787, from Miller to Adams (Mss2M6163a1). There is also an undated letter from the wife of Adams's brother, Elizabeth (Griffin) Adams (1736–1800) of Richmond, regarding Thomas Adams's marriage to the widow Elizabeth (Fauntleroy) Turner Cocke (1736–1792) of Bremo in Henrico County (section 6). Papers of Elizabeth Cocke Adams, include a letter, 1791, to her son, William Cocke (1758–1835), about finances; a personal account, 1789– 1790, with her husband's executor, Thomas Massie; and inventories, 1792, of her estate in Amherst and Cumberland counties (section 11). Other legal and economic papers that feature women appear scattered throughout the collection; they include the wills, 1743 and 1744, of Sarah (Adams) Atkinson of London (section 3) and Ann Adams of Westham, Eng. -

John Tyler Before the Presidency: Principles and Politics of a Southern Planter

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 John Tyler Before the Presidency: Principles and Politics of a Southern Planter. Christopher Joseph Leahy Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Leahy, Christopher Joseph, "John Tyler Before the Presidency: Principles and Politics of a Southern Planter." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

M Master R Proje Ect Bib Bliogr Raphy

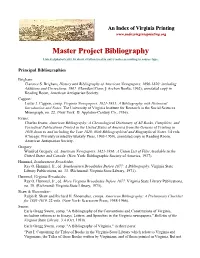

An Index of Virginia Printing www.indexvirginiaprinting.org Master Project Bibliography Listed alphabetically by short citation used in entrry notes according to source type. Principal Bibliographies Brigham: Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newsppapers, 16900-1820: including Additions and Corrections, 1961. (Hamden [Conn.]: Archon Books, 1962); annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Cappon: Lester J. Cappon, comp. Virginia Newspapers, 1821-1935: A Biblioggraphy with Historical Introduction and Notes. The University of Virginia Institute for Research in the Social Sciences Monograph, no. 22. (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1936). Evans: Charles Evans, American Bibliography: A Chronological Dictionary of All Books, Pamphlets, and Periodical Publications Printed in the United States of America from the Genesis of Printing in 1639 down to and including the Year 1820: With Bibliographical and Biographical Notes. 14 vols. (Chicago: Privately printed by Blakely Press, 1903-1959), annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Gregory: Winifred Gregory, ed. American Newspapers, 1821-1936: A Union List of Files Available in the United States and Canada. (New York: Bibliographic Society of America, 1937). Hummel, Southeastern Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. Southeastern Broadsides Before 1877: A Bibliography. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 33. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1971). Hummel, Virginia Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. More ViV rginia Broadsides Beforre 1877. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 39. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1975). Shaw & Shoemaker: Ralph R. Shaw and Richard H. Shoemaker, comps. American Bibliography: A Preliminary Checklist for 1801-1819. 22 vols. (New York: Scarecrow Press, 1958-1966). Swem: Earle Gregg Swem, comp. -

National Police Power Under the Postal Clause of the Constitution Robert Eugene Cushman

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1920 National Police Power under the Postal Clause of the Constitution Robert Eugene Cushman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Cushman, Robert Eugene, "National Police Power under the Postal Clause of the Constitution" (1920). Minnesota Law Review. 2188. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2188 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW NATIONAL POLICE POWER UNDER THE POSTAL CLAUSE OF THE CONSTITUTION IF ONE were asked to explain and illustrate the doctrine of implied powers as it has functioned in the development of our constitutional law, there would probably be no easier way to do it than to point to the enormous expansion of the postal power of Congress.' The clause in the federal constitution which grants to Congress the power "to establish Post Offices and Post Roads"2 was inserted there -almost without discussion. 3 It seems to have appeared entirely innocuous even to the most suspicious and skeptical of those who feared that the new government would dangerously expand its powers at the expense of the states and the individual.4 And yet that government had hardly been set in operation before this brief grant of aufhority began to be subjected to a liberal and expansive construction under which our postal system has come to be our most picturesque symbol of the length and breadth and strength of national authority.5 1 The subject of the expansion of the postal power of Congress has been fully treated in a very excellent monograph by Lindsay Rogers entitled "The Postal Power of Congress," Johns Hopkins' University Stu- dies in Historical and Political Science, 1916.