DANCING REVELATIONS Defrantz.00 FM 10/20/03 2:50 PM Page Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donald Mckayle's Life in Dance

ey rn u In Jo Donald f McKayle’s i nite Life in Dance An exhibit in the Muriel Ansley Reynolds Gallery UC Irvine Main Library May - September 1998 Checklist prepared by Laura Clark Brown The UCI Libraries Irvine, California 1998 ey rn u In Jo Donald f i nite McKayle’s Life in Dance Donald McKayle, performer, teacher and choreographer. His dances em- body the deeply-felt passions of a true master. Rooted in the American experience, he has choreographed a body of work imbued with radiant optimism and poignancy. His appreciation of human wit and heroism in the face of pain and loss, and his faith in redemptive powers of love endow his dances with their originality and dramatic power. Donald McKayle has created a repertory of American dance that instructs the heart. -Inscription on Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival Award orld-renowned choreographer and UCI Professor of Dance Donald McKayle received the prestigious Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival WAward, “established to honor the great choreographers who have dedicated their lives and talent to the creation of our modern dance heritage,” in 1992. The “Sammy” was awarded to McKayle for a lifetime of performing, teaching and creating American modern dance, an “infinite journey” of both creativity and teaching. Infinite Journey is the title of a concert dance piece McKayle created in 1991 to honor the life of a former student; the title also befits McKayle’s own life. McKayle began his career in New York City, initially studying dance with the New Dance Group and later dancing professionally for noted choreographers such as Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, Sophie Maslow, and Anna Sokolow. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ------X in Re : Chapter 11 : MOTORS LIQUIDATION COMPANY, Et Al., : Case No

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------------------x In re : Chapter 11 : MOTORS LIQUIDATION COMPANY, et al., : Case No. 09-50026 (REG) f/k/a General Motors Corp., et al., : : Debtors. : (Jointly Administered) : ------------------------------------------------------------------x AMENDED AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF NEW YORK ) ) ss: COUNTY OF SUFFOLK ) I, Barbara Kelley Keane, being duly sworn, depose and state: 1. I am an Assistant Director with The Garden City Group, Inc., the claims and noticing agent for the debtors and debtors-in-possession (the “Debtors”) in the above-captioned proceeding. Our business address is 105 Maxess Road, Melville, New York 11747. 2. Between August 19, 2010 and August 20, 2010, at the direction of Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP, counsel for the Debtors in the above-captioned case and pursuant to the Notice of Debtors’ Seventy- Fourth Omnibus Objection to Claims [Docket No. 6684], I caused to be served a customized Notice of Objection to Individual Debt Claims, a copy of which is annexed hereto as Exhibit “A”, upon each of the parties set forth in Exhibit “B” annexed hereto (affected parties) by depositing same in a sealed, postage paid envelope at a United States Post Office for delivery by the United States Postal Service via First Class Mail. /s/ Barbara Kelley Keane Barbara Kelley Keane Sworn to before me this 9th day of September 2010 /s/ Eamon Mason_______________ Eamon Mason Notary Public, State of New York No. 01MA6187254 Qualified in Manhattan County Commission Expires: May 19, 2012 EXHIBIT A PLEASE CAREFULLY REVIEW THIS NOTICE AS IT WILL AFFECT YOUR CLAIM IN THE GENERAL MOTORS CORPORATION (NOW MOTORS LIQUIDATION COMPANY) BANKRUPTCY CASE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------x : In re : Chapter 11 Case No. -

Welcome Letter 2013 Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival

Welcome Letter 2013 Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award Lin Hwai-min The ADF wishes to thank the late Samuel H. Scripps, whose generosity made possible the annual $50,000 Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award. The Award was established in 1981 as the first of its kind and honors chorographers who have dedicated their lives and talent to the creation of modern dance. The continuation of the award is made possible through the SHS Foundation and its President, Richard E. Feldman. Celebrated choreographer, director, and educator Lin Hwai-min will be presented with the 2013 Award by Joseph V. Melillo in a special ceremony on Saturday, July 27th at 8:00 pm, prior to the Forces of Dance performance at the Durham Performing Arts Center. The program will also include a performance of the solo from Lin Hwai-min’s 1998 work Moon Water, performed by Cloud Gate Dance Theatre dancer Chou Chang-ning. Mr. Lin’s fearless zeal for the art form has established him as one of the most dynamic and innovative choreographers today. His illustrious career as a choreographer has spanned over four decades and has earned him international praise for his impact on Chinese modern dance. He is the founder, choreographer, and artistic director of both Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan (founded in 1973) and Cloud Gate 2 (founded in 1992), and his choreography continues to be presented throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia. While his works often draw inspiration from traditional elements of Asian culture and aesthetics, his choreographic brilliance continues to push boundaries and redefine the art form. -

Layout 1 (Page 1

In 1949, Janet Collins—the first Black artist to appear Jean-Léon Destiné’s company along with Spanish and African Artists of the African Diaspora on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera—and Jean-Léon Hindu dances. It was a bold move, and its legacy is seen Destiné made their debut appearances at Jacob’s Pillow. today in the all-encompassing dance programming at Famous for his work with Katherine Dunham, Destiné Jacob’s Pillow. In 1970 Ted Shawn presented Dance Theatre and Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival: was the first of many Black artists to teach in The School of Harlem’s first formal “engagement.” Critic Walter Terry American at Jacob’s Pillow in 1949, and returned to direct the praised the company’s debut and Shawn referred to the Inception to Present Cultural Traditions Program in 2004. Over 100 students Dance Theatre of Harlem performance as a “highlight of from around the world attend this professional-track the summer.” School at Jacob’s Pillow each year. f v f Heritage Beginning in the 1980s, African-American companies The ground-breaking Lester Horton Dance Theatre appeared at the Pillow more and more frequently. “Dance includes every way that men of all races in every period of the made its Pillow debut in 1953. Several of its young Highlights since then have included engagements by Participate in African Diaspora activities at JACOB’S PILLOW DANCE members, James Truitte, Carmen de Lavallade, and tappers Savion Glover, Gregory Hines and Jimmy Jacob’s Pillow Dance world’s history have moved rhythmically to express themselves.”—Ted Shawn (1915) Alvin Ailey, would leave a lasting impression on the Slyde, hip-hop from Rennie Harris, and world premiere dance world. -

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

Lyn C. Wiltshire

Lyn C. Wiltshire University of Texas at Austin, Department of Theatre and Dance Winship 2.132E, Campus Code D3900 Austin, TX 78712 Phone: 512-232-5331, Fax: 512-471-0824, E-Mail: [email protected] EDUCATION B.A. Dance Studies, State University of New York (Empire State College) ACADEMIC/PROFESSIONAL WORK EXPERIENCE University of Texas at Austin 1995 - Present Professor and Head of Dance 2010 - Present Associate Chair and Head of Performance Unit and Dance Program 2007 - 2010; Associate Professor of Dance 2001 - Present Associate Chair of Undergraduate Education 2003 - 2005 Assistant Director of Undergraduate Education 2005 - Present Head of Dance Program 2000 - 2004 Assistant Professor of Dance 1995 - 2000 L'A.R.T. Dance Project 2004 - Present Artistic Director Ball State University 1992 - 1995 Assistant Professor Butler University 1991 - 1995 Adjunct Instructor Rehearsal Assistant Purdue University 1991 - 1995 Guest Artist in Residence CHOREOGRAPHY (My Repertory of Ballets consists of 60 Works from 1987-2008. A complete chronology and video excerpts are available upon request) 2006, 2007, 2008 Hora Tango Alexandra Ballet Company, St. Louis, Missouri, 2008; Mi Di Te Salzburg International Ballet Workshop - Salzburg, Austria; Fantasie European Dance Arts - EDAS Cyprus 2008, Restaged: Salzburg International Ballet Workshop; Psalm European Dance Arts - EDAS Cyprus; All Holy Children Sing: European Dance Arts - EDAS Cyprus; Tous Les Nous Dance Repertory Theatre, Tanzsommer Austria; Paralyzed Dance Repertory Theatre, Tanzsommer Austria; Remembering Qualities Dance Repertory Theatre, University of Texas at Austin; HeartSteps Central Indiana Dance Ensemble, Mid-States Regional Festival 2008; General Truths: based on limited and incomplete evidence Dance Repertory Theatre, University of Texas at Austin, 2006 Tanzsommer Austria, Restaged for: Ballet East Dance Theatre 2006; Designer Genes Dance Repertory Theatre, University of Texas at Austin 2006 1 Lyn C. -

Mccarter THEATRE CENTER FOUNDERS Arthur Mitchell Karel

McCARTER THEATRE CENTER William W. Lockwood, Jr. Michael S. Rosenberg SPECIAL PROGRAMMING DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR presents FOUNDERS Arthur Mitchell Karel Shook ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Virginia Johnson Anna Glass BALLET MASTER INTERIM GENERAL MANAGER Marie Chong Melinda Bloom DANCE ARTISTS Lindsey Donnell, Yinet Fernandez, Alicia Mae Holloway, Alexandra Hutchinson, Daphne Lee, Crystal Serrano, Ingrid Silva, Amanda Smith, Stephanie Rae Williams, Derek Brockington, Kouadio Davis, Da’Von Doane, Dustin James, Choong Hoon Lee, Christopher McDaniel, Sanford Placide, Anthony Santos, Dylan Santos ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EMERITUS Arthur Mitchell Please join us after this performance for a post-show conversation with Artistic Director Virginia Johnson. SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2020 The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment of any kind during performances is strictly prohibited. Support for Dance Theatre of Harlem’s 2019/2020 professional Company and National Tour activities made possible in part by: Anonymous, The Arnhold Foundation; Bloomberg Philanthropies, The Dauray Fund; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; Elephant Rock Foundation; Ford Foundation; Ann & Gordon Getty Foundation; Harkness Foundation for Dance; Howard Gilman Foundation; The Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund; The Klein Family Foundation; John L. McHugh Foundation; Margaret T. Morris Foundation; National Endowment for the Arts, New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; New England -

ROUTES, a Guide to Black Entertainment January 1978 As

Pub isher SStatement s you start the new year with new paths of hope. ROUTES Magazine at your As the Publisher of ROUTES A fingertip , think not of starting Magazine, I promise that the entire a new year per se, but think of begin ROUTES family will work hard to ning a new way of living. At this period make 1978 a year in which your leisure of time, most of us reflect on what has time can be used to the fullest and a occurred in the past year. It is a time to year that will be as entertaining for you calculate and assess your gains and it is as it will be for us . a time to realize that perhaps there were Our wish is that as you turn the pages of no losses after all. It is a time to place ROUTES, you will find just the right the events of the past year in their activity, product or message. proper perspectives. Realizing that no We warmly welcome our new subscrib matter how fruitless or no matter how ers and advertisers. We wish each of vain, you have gained some ground by you a HAPPY NEW YEAR. traveling new routes of new values and PUBLISHER 4 ROUTES, A Guide to Black Entertainment, January 1978 ROUTES MAGAZINE, A Guide to Black Entertainment. Our cover was photographed by Anthony Barboza. Furs provided by Alvin Campbell, 352 Seventh Avenue. Dress provided by D. Willis of F.I.D.C., 253 West 26th Street. Male attire provided by Van Gils, Inc., 40 West 55th Street. -

Theresa Payton

COLUMBUS, GA | AUGUST 31 | AUGUST GA COLUMBUS, PRESENTED BY The Forum 2021 | Leadership Reinvented | Leadership Institute at Columbus State University table of Theresa Payton contentsAGENDA 3 12 LETTERS 4 Executive Director Shana Young Tara President Chris Markwood Westover Acting Chancellor Teresa MacCartney 14 Governor Brian Kemp OUR TEAM 8 Photo Credit: Paul Stuart DINE AROUND 10 BOOK SIGNINGS 11 Kat SPEAKERS 12 Cole Theresa Payton 20 Tara Westover Debbie Kat Cole Allen Debbie Allen 22 Norman Nixon HONORS 18 2021 Blanchard Award 2021 Helton Scholarship OUR LEADERSHIP 26 Norman LEGACY Nixon 2021 SPONSORS 30 24 The leadership effect. Your impact starts here. As a founding sponsor, Synovus is proud to welcome you to the 16th Annual Forum at CSU. A true leader endeavors to awaken the leadership qualities of others. This has long been the inspiration behind the leadership of our company and the vision behind an epic annual gathering of the world’s brightest minds right here in our community. It is our hope you will discover the true leader within and be challenged to have an impact that will inspire others to lead as well. We call it the leadership effect. 1-888-SYNOVUS | synovus.com Synovus Bank, Member FDIC. The Forum 2021 | Leadership Reinvented | Leadership Institute at Columbus State University event agenda Registration 8:00 am Welcome 9:00 am Shana Young, Assistant Vice President of Leadership Development and Executive Director, Leadership Institute at Columbus State University Dr. Chris Markwood, President, Columbus State University -

1 of 6 a I R L I N E S FAA/Shrinking Seats the Federal Aviation

AIRLINES FAA/Shrinking The Federal Aviation Administration has been directed to investigate the case of the Seats incredible shrinking airline seat. Issues: safety concerns, cramped conditions and the plight of large passengers. Note: In 2016, the House and Senate rejected measures that would have required the F.A.A. to set minimum seat-size standards. AUTOMOTIVE Sales The Wall Street Journal reported that auto sales declined sharply in July, continuing a 7-month slowdown punctuated by manufacturers’ reluctance to sell discounted cars through leases and car rental chains, which has driven sales in recent years. According to Autodata Corp., sales fell 7% last month compared with a year earlier. Uber/Barclay Ride hailing entity Uber is partnering with British bank Barclays to issue its own co- branded credit card. BROADCAST E.W. Scripps/Katz TV station group E.W. Scripps (33 TV stations) purchased Katz Broadcasting’s four Networks networks (diginets) – Bounce (African America centric), Grit (action and western), Escape (mystery and investigative) and Laff (comedy) – for $302 million. Fox/ION Rumors are circulating that 21st Century Fox and ION Media Networks (60 TV stations) are contemplating creating a joint venture that would combine their respective local TV station holdings. CABLE Discovery/Scripps Discovery agreed to acquire Scripps Networks for $11.9 billion. Two benefits sighted from a combined entity: redundancy reductions and leverage in negotiating higher distribution fees. The Wall Street Journal reported that a combined Discovery -

Window Dancing

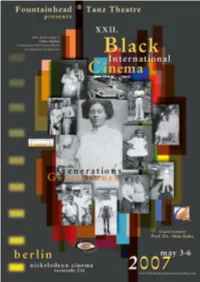

In Memoriam Harold Francis McKinney May 28, 1917 – November 7, 2006 The Talented Tenth “The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth: it is the problem of developing the best of this race that they may guide the mass away from the contamination of the worst, in their own and other races.” W.E.B. DuBois FOREWORD Generations “A term referring to an approximation between the age of parents and the time their children were born.” The issue is, what has ensued during the generational time span of 20-25 years and how prepared were and are parents to provide the necessary educational, emotional, spiritual, physical and economic assets required for the development of the oncoming generations? What have been the experiences, accomplishments and perhaps inabilities of the parent generation and how will this equation impact upon the newcomers entering the world? The constant quest for human development is hopefully not supplanted by neglect, per- sonal or societal and therefore the challenge for each generation; are they prepared for their “turn” at the wheel of anticipated progress? How does each generation cope with the accomplishments and deficiencies from the previ- ous generation, when the baton is passed to the next group competing in the relay race of human existence? Despite the challenge of societal imbalance to the generations, hope and effort remain the constant vision leading to improvement accompanied and reinforced by determination and possible occurrences of “good luck,” to assist the generations and their offspring, neigh- bors and other members of the human family, towards as high a societal level as possible, in order to preserve, protect and project the present and succeeding generations into posi- tions of leverage thereby enabling them to confront the vicissitudes of life, manmade or otherwise.