Lethbridge County's Tax on Confined Feeding Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subdivision Applications and Providing Municipal District of Taber Recommendations

What is ORRSC? MEMBER MUNICIPALITIES Oldman River Regional The Oldman River Regional Services Services Commission Commission (ORRSC) is a cooperative effort of 41 municipalities in southwestern Alberta that provides municipal planning services to Rural: Cardston County Lethbridge County its members. County of Newell Municipal District of Pincher Creek No. 9 ORRSC is responsible for processing Municipal District of Ranchland No. 66 subdivision applications and providing Municipal District of Taber recommendations. The final decision lies Vulcan County with the local municipal Subdivision County of Warner No. 5 BEFORE YOU Authority. Municipal District of Willow Creek No. 26 City: Brooks SUBDIVIDE What is Subdivision? Subdivision is the division of land into 2 or more parcels, each to be given a separate Towns: Municipality of Crowsnest Pass Bassano Milk River title. Cardston Nanton Claresholm Picture Butte Subdivision approval is also required for title Coaldale Pincher Creek separations, property line adjustments, Coalhurst Raymond bareland condominiums and the registration Fort Macleod Stavely of long-term leases. Granum Vauxhall Magrath Vulcan Who Makes the Rules? Villages: Arrowwood Glenwood Barnwell Hill Spring The Province — through the Municipal Barons Lomond Government Act, the Subdivision and Carmangay Milo Development Regulation, and any other Champion Nobleford Government department. Coutts Stirling Cowley Warner The Municipality — through the land use bylaw and adopted statutory plans including Municipal Development Plans, -

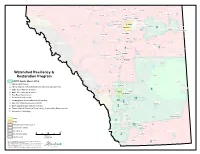

Watershed Resiliency and Restoration Program Maps

VU32 VU33 VU44 VU36 V28A 947 U Muriel Lake UV 63 Westlock County VU M.D. of Bonnyville No. 87 18 U18 Westlock VU Smoky Lake County 28 M.D. of Greenview No. 16 VU40 V VU Woodlands County Whitecourt County of Barrhead No. 11 Thorhild County Smoky Lake Barrhead 32 St. Paul VU County of St. Paul No. 19 Frog Lake VU18 VU2 Redwater Elk Point Mayerthorpe Legal Grande Cache VU36 U38 VU43 V Bon Accord 28A Lac Ste. Anne County Sturgeon County UV 28 Gibbons Bruderheim VU22 Morinville VU Lamont County Edson Riv Eds er on R Lamont iver County of Two Hills No. 21 37 U15 I.D. No. 25 Willmore Wilderness Lac Ste. Anne VU V VU15 VU45 r Onoway e iv 28A S R UV 45 U m V n o o Chip Lake e k g Elk Island National Park of Canada y r R tu i S v e Mundare r r e Edson 22 St. Albert 41 v VU i U31 Spruce Grove VU R V Elk Island National Park of Canada 16A d Wabamun Lake 16A 16A 16A UV o VV 216 e UU UV VU L 17 c Parkland County Stony Plain Vegreville VU M VU14 Yellowhead County Edmonton Beaverhill Lake Strathcona County County of Vermilion River VU60 9 16 Vermilion VU Hinton County of Minburn No. 27 VU47 Tofield E r i Devon Beaumont Lloydminster t h 19 21 VU R VU i r v 16 e e U V r v i R y Calmar k o Leduc Beaver County m S Leduc County Drayton Valley VU40 VU39 R o c k y 17 Brazeau County U R V i Viking v e 2A r VU 40 VU Millet VU26 Pigeon Lake Camrose 13A 13 UV M U13 VU i V e 13A tt V e Elk River U R County of Wetaskiwin No. -

AAFRD Regions County Willow Creek 1 Ranchland Taber (MD 66) (MD 26) Lethbridge (MD 14) (Co

Mackenzie (MD 23) Wood Buffalo Park (ID 24) Northern Lights (MD 22) Wood Buffalo (Regional) Clear Hills (MD 21) East Peace (MD 131) 5 Opportunity (MD 17) MD Fairview 135 (MD 136) Saddle Hills County MD Birch Hills 133 (MD 19) Smoky River 3 (MD 130) Grande Prairie M.D. Lesser Slave River (Co. 1) of (MD 124) Big Lakes Lakeland County Athabasca (Co. 12) Greenview (MD 16) Bonnyville (MD 87) Woodlands County Thorhild Smoky Lake Barrhead Westlock (Co. 7) (Co. 11) (Co. 13) County St. Paul (Co.19) Lac Ste. Anne Sturgeon Lamont Willmore (Co. 28) County (Co. 30) Two Hills (Co. 21) Wilderness (ID 25) Strathcona Vermilion Parkland (Co. 31) (Co. 20) Minburn (Co. 27) Yellowhead County 4 River Beaver (Co.9) (Co. 24) Brazeau Leduc (Co. 25) (MD 77) Jasper ID Wetaskiwin (Co. 10) Camrose Wainwright (Co. 22) Flagstaff (MD 61) Jasper Park (Co. 29) (ID 12) Ponoka (Co. 3) Provost Lacombe (Co. 14) (MD 52) Clearwater (MD 99) Stettler Paintearth (Co. 6) (Co. 18) Red Deer (Co. 23) Consort (S.A. 4) Mountain View Kneehill Starland 2 (Co. 17) County County Oyen Banff Park Bighorn Hanna 1 South (S.A. 2) (S.A. 3) (ID 9) (MD 8) Rocky View 2 Central (MD 44) Wheatland Acadia 3 North East (Co. 16) (MD 34) 4 North West 5 Peace Kananaskis Newell (ID 5) Foothills (Co. 4) (MD 31) Vulcan (Co. 2) Cypress AAFRD Regions County Willow Creek 1 Ranchland Taber (MD 66) (MD 26) Lethbridge (MD 14) (Co. 26) Forty Mile Pincher Creek Warner (Co. 8) (MD 9) Cardston (Co. -

Communities Within Specialized and Rural Municipalities (May 2019)

Communities Within Specialized and Rural Municipalities Updated May 24, 2019 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] COMMUNITIES WITHIN SPECIALIZED AND RURAL MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES COMMUNITY STATUS MUNICIPALITY Abee Hamlet Thorhild County Acadia Valley Hamlet Municipal District of Acadia No. 34 ACME Village Kneehill County Aetna Hamlet Cardston County ALBERTA BEACH Village Lac Ste. Anne County Alcomdale Hamlet Sturgeon County Alder Flats Hamlet County of Wetaskiwin No. 10 Aldersyde Hamlet Foothills County Alhambra Hamlet Clearwater County ALIX Village Lacombe County ALLIANCE Village Flagstaff County Altario Hamlet Special Areas Board AMISK Village Municipal District of Provost No. 52 ANDREW Village Lamont County Antler Lake Hamlet Strathcona County Anzac Hamlet Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo Ardley Hamlet Red Deer County Ardmore Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87 Ardrossan Hamlet Strathcona County ARGENTIA BEACH Summer Village County of Wetaskiwin No. 10 Armena Hamlet Camrose County ARROWWOOD Village Vulcan County Ashmont Hamlet County of St. Paul No. 19 ATHABASCA Town Athabasca County Atmore Hamlet Athabasca County Balzac Hamlet Rocky View County BANFF Town Improvement District No. 09 (Banff) BARNWELL Village Municipal District of Taber BARONS Village Lethbridge County BARRHEAD Town County of Barrhead No. 11 BASHAW Town Camrose County BASSANO Town County of Newell BAWLF Village Camrose County Beauvallon Hamlet County of Two Hills No. 21 Beaver Crossing Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. 87 Beaver Lake Hamlet Lac La Biche County Beaver Mines Hamlet Municipal District of Pincher Creek No. 9 Beaverdam Hamlet Municipal District of Bonnyville No. -

AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region

AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region AREA Chief Economist https://albertare.configio.com/page/ann-marie-lurie-bioAnn-Marie Lurie analyzes Alberta’s resale housing statistics both provincially and regionally. In order to allow for better analysis of housing sales data, we have aligned our reporting regions to the census divisions used by Statistics Canada. Economic Region AB-NW: Athabasca – Grande Prairie – Peace River 17 16 Economic Region AB-NE: Wood Buffalo – Cold Lake Economic Region AB-W: 19 Banff – Jasper – Rocky Mountain House 18 12 Economic Region AB-Edmonton 13 14 Economic Region AB-Red Deer 11 10 Economic Region AB-E: 9 8 7 Camrose – Drumheller 15 6 4 5 Economic Region AB-Calgary Economic Region AB-S: 2 1 3 Lethbridge – Medicine Hat New reports are released on the sixth of each month, except on weekends or holidays when it is released on the following business day. AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region 1 Alberta Economic Region North West Grande Prairie – Athabasca – Peace River Division 17 Municipal District Towns Hamlets, villages, Other Big Lakes County - 0506 High Prairie - 0147 Enilda (0694), Faust (0702), Grouard Swan Hills - 0309 (0719), Joussard (0742), Kinuso (0189), Rural Big Lakes County (9506) Clear Hills – 0504 Cleardale (0664), Worsley (0884), Hines Creek (0150), Rural Big Lakes county (9504) Lesser Slave River no 124 - Slave Lake - 0284 Canyon Creek (0898), Chisholm (0661), 0507 Flatbush (0705), Marten Beach (0780), Smith (0839), Wagner (0649), Widewater (0899), Slave Lake (0284), Rural Slave River (9507) Northern Lights County - Manning – 0212 Deadwood (0679), Dixonville (0684), 0511 North Star (0892), Notikewin (0893), Rural Northern Lights County (9511) Northern Sunrise County - Cadotte Lake (0645), Little Buffalo 0496 (0762), Marie Reine (0777), Reno (0814), St. -

Lethbridge County Municipal District of Willow Creek Intermunicipal

Lethbridge County and Municipal District of Willow Creek Intermunicipal Development Plan Lethbridge County Bylaw 19-014 MD of Willow Creek Bylaw 1831 May 2019 LETHBRIDGE COUNTY IN THE PROVINCE OF ALBERTA BYLAW 19.014 BEING a bylaw of Lethbridge County in the Province of Alberta, to adopt an lntermunicipal Development Plan between Lethbridge County and the Municipal District of Willow Creek pursuant to Sections 631 and 692 of the Municipal Government Act, Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000, Chapter M-26, as amended; WHEREAS municipalities are required by the Province to expand intermunicipal planning efforts to address planning matters that transcend municipal boundaries through an intermunicipal development plan; AND WHEREAS both the Councils of Lethbridge County and the Municipal District of Willow Creek agree that it is to their mutual benefit to establish joint planning policies and this negotiation and agreement reflects a continuing cooperative approach between the two municipalities and the desire to see well- planned, orderly, and managed growth. AND WHEREAS the municipality must prepare a corresponding bylaw and provide for its consideration at a public hearing. NOW THEREFORE, under the authority and subject to the provisions of the Municipal Government Act, Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000, Chapter M-26 as amended, the Council of Lethbridge County duly assembled hereby enacts the following: 1. That the Lethbridge County and Municipal District of Willow Creek lntermunicipal Development Plan, attached hereto, be adopted. 2. This plan, upon adoption, shall be cited as the Lethbridge County and Municipal District of Willow Creek lntermunicipal Development Plan Bylaw No. 1831 and Bylaw No. 19-014. -

Alberta Municipalities Classified by Region*

Alberta Municipalities Classified by Region* South Region* Central Region* North East Region* Legal Name AMC Reference Legal Name AMC Reference Legal Name AMC Reference Cardston County ------- M.D. No. 6 Acadia No. 34 MD 34 M.D. No. 34 Beaver County ------- County No. 9 Cypress County ------- M.D. No. 1 Bighorn No. 8 MD 8 M.D. No. 8 Bonnyville No. 87 MD 87 M.D. No. 87 Foothills No. 31 MD 31 M.D. No. 31 Calgary ------- Calgary Camrose County No. 22 CO 22 County No. 22 Forty Mile County No. 8 CO 8 County No.8 Clearwater County ------- M.D. No. 99 Flagstaff County ------- County No. 29 Lethbridge County ------- County No. 26 Kneehill County ------- M.D. No. 48 Lakeland County ------- M.D. No. 87 Newell County No. 4 CO 4 County No. 4 Lacombe County ------- County No. 14 Lamont County ------- County No. 30 Pincher Creek No. 9 MD 9 M.D. No. 9 Mountain View County ------- County No. 17 Minburn County No. 27 CO 27 County No. 27 Ranchland No. 66 MD 66 M.D. No. 66 Paintearth County No. 18 CO 18 County No. 18 Opportunity No. 17 MD 17 M.D. No. 17 Taber MD M.D. No. 14 Ponoka County ------- County No. 3 Provost No. 52 MD 52 M.D. No. 52 Vulcan County ------- County No. 2 Red Deer County ------- County No. 23 Smoky Lake County ------- County No. 13 Warner County No. 5 CO 5 County No. 5 Rocky View No. 44 MD 44 M.D. No. 44 St. Paul County No. 19 CO 19 County No. -

Services Commissions and Their Municipalities (December 2017)

Services Commissions and Their Municipalities Updated December 04, 2017 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] SERVICES COMMISSIONS AND THEIR MUNICIPALITIES SERVICES COMMISSION MUNICIPALITY COMMUNITY STATUS Alberta Capital Region Wastewater Commission Fort Saskatchewan City Leduc City Spruce Grove City St. Albert City Strathcona County Specialized Municipality Leduc County Municipal District Parkland County Municipal District Sturgeon County Municipal District Beaumont Town Bon Accord Town Gibbons Town Morinville Town Stony Plain Town Aqua 7 Regional Water Commission Kneehill County Municipal District Rocky View County Municipal District Irricana Town Acme Village Beiseker Village Carbon Village Linden Village Aspen Regional Water Services Commission Athabasca County Municipal District Athabasca Town Boyle Village Athabasca Regional Waste Management Services Commission Athabasca County Municipal District Lesser Slave River No. 124, M.D. of Municipal District Athabasca Town Boyle Village Barrhead Regional Water Commission Barrhead No. 11, County of Municipal District Barrhead Town Beaver Emergency Services Commission Beaver County Municipal District Tofield Town December 04, 2017 Page 1 of 14 SERVICES COMMISSION MUNICIPALITY COMMUNITY STATUS Viking Town Holden Village Ryley Village Beaver Regional Waste Management Services Commission Beaver County Municipal District Tofield Town Viking Town Holden Village Ryley Village Beaver River Regional Waste Management Commission Cold Lake City Bonnyville No. 87, M.D. of Municipal District Bonnyville Town Bonnyville Beach Summer Village Pelican Narrows Summer Village Big Country Waste Management Services Commission Acadia No. 34, M.D. of Municipal District Hanna Town Oyen Town Cereal Village Consort Village Empress Village Veteran Village Youngstown Village Special Areas No. -

Municipalities Assessed Using Camalot XXX = Not Using Camalot

Municipalities Assessed Using CAMAlot XXX = not using CAMAlot CITIES Airdrie Edmonton Leduc Red Deer Brooks Fort Saskatchewan Lethbridge Spruce Grove Calgary Grande Prairie Lloydminster St. Albert Camrose Lacombe Medicine Hat Wetaskiwin Cold Lake SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY Crowsnest Pass Strathcona County Mackenzie County Wood Buffalo (only Ind) Jasper MUNICIPAL DISTRICTS Acadia, M.D. of Foothills, M.D. of Northern Sunrise County Starland County Athabasca County Forty Mile, County of Opportunity, M.D. of Stettler, County of Barrhead, County of Grande Prairie, County of Paintearth, County of Sturgeon County Beaver County Greenview, M.D. of Parkland County Taber, M.D. of Big Lakes, M.D. of Kneehill County Peace, M.D. of Thorhild, County of Bighorn, M.D. of Lac La Biche County Pincher Creek, M.D. of Two Hills, County of Birch Hills County Lac Ste. Anne County Ponoka County Vermilion River, County of Bonnyville, M.D. of Lacombe County Provost, M.D. of Vulcan County Brazeau County Lamont County Ranchland, M.D. of Wainwright, M.D. of Camrose County Leduc County Red Deer County Warner, County of Cardston County Lesser Slave River, M.D. Rocky View County Westlock County Clear Hills County Lethbridge, County of Saddle Hills County Wetaskiwin, County of Clearwater County Minburn, County of Smoky Lake County Wheatland County Cypress County Mountain View County Smoky River, M.D. of Willow Creek, M.D. of Fairview, M.D. of Newell, County of Spirit River, M.D. of Woodlands County Flagstaff County Northern Lights, County of St. Paul, County of Yellowhead County TOWNS Athabasca Daysland Magrath Slave Lake Banff Devon Manning Smoky Lake Barrhead Didsbury Mayerthorpe Spirit River Bashaw Drayton Valley McLennan St. -

The Economic Contribution of Rural Alberta Submitted To

The Economic Contribution of Rural Alberta Submitted to: The Alberta Association of Municipal Districts and Counties Submitted by: Nichols Applied Management Inc. Management and Economic Consultants Suite 2401, 10104 – 103 Avenue NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 0H8 January 30, 2018 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 4 3. Study Approach ................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Data ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Analysis ................................................................................................... 5 3.3 Outlook .................................................................................................... 6 4. Economic Profiles ................................................................................................ 7 4.1 Overview of Rural Alberta ........................................................................ 7 4.2 Rural Alberta .......................................................................................... 10 4.3 South Region ......................................................................................... 15 4.4 East Region ........................................................................................... 23 -

Lethbridge County

LETHBRIDGE COUNTY Hamlet of Shaughnessy GROWTH STUDY DRAFT – December 2020 © 2020 Oldman River Regional Services Commission Prepared for Lethbridge County This document is protected by Copyright and Trademark and may not be reproduced or modified in any manner, or for any purpose, except by written permission of the Oldman River Regional Services Commission. This document has been prepared for the sole use of the Municipality addressed and the Oldman River Regional Services Commission. This disclaimer is attached to and forms part of the document. TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 STUDY OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Intent .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives ........................................................................................................................... 1 Part 2 LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... 3 Part 3 HAMLET OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Population ........................................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Hamlet History .................................................................................................................... 5 Map 1 ‐ Location Part 4 EXISTING CONDITIONS -

COVID-19: High Case Regions Additional Restrictions Are in Effect for Regions with High Active Cases

COVID-19: High case regions Additional restrictions are in effect for regions with high active cases. Stop the spike New mandatory health restrictions on outdoor social gatherings, retail, restaurants, places of worship, personal and wellness services, outdoor sports and fitness, funerals and schools, starting May 5. These measures apply to all Albertans, businesses, organizations and service providers in municipalities or areas with more than 50 cases per 100,000 people, and with more than 30 active cases. Visit alberta.ca/StopTheSpike to see all restrictions. High case regions As of May 4, the following municipalities have more than 50 cases per 100,000 people and more than 30 active cases. View the regional active cases page for up-to-date information. Case numbers are updated every afternoon. • Wheatland County • I.d. No. 9 (Banff) • City Of Red Deer • Town Of Hinton • Town Of Whitecourt • Fort McMurray • Cypress County • County Of Barrhead No. 11 • City Of Edmonton • Yellowhead County • Leduc County • City Of Calgary • Town Of Morinville • Foothills County • Beaver County • County Of Warner No. 5 • County Of Vermilion River • County Of Stettler No. 6 • City Of Brooks • Town Of Olds • M.D. of Lesser Slave River No. 124 • Town Of Strathmore • County Of St. Paul No. 19 • City Of Chestermere • M.D. of Taber • Lac La Biche County • Camrose County • City Of Camrose • City Of Cold Lake • City Of Spruce Grove • Wood Buffalo • City Of Fort Saskatchewan • County Of Wetaskiwin No. 10 • Town Of Sylvan Lake • Cardston County • Parkland County • Town Of Canmore • Ponoka County • Westlock County • Lethbridge County • Town Of High River • Mackenzie County • Athabasca County • City Of Leduc • Kneehill County • City Of Lacombe • City Of Wetaskiwin • Lacombe County • Town Of Stony Plain • County Of Grande Prairie No.