The Bristol Region in the Sub-Roman and Early Anglo-Saxon Periods Is the Social Signifiers Extends Easily Into the Realms of the Symbolic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Ii ©[2014] Susanna Polihros ALL RIGHTS RESERVED](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6761/ii-%C2%A9-2014-susanna-polihros-all-rights-reserved-56761.webp)

Ii ©[2014] Susanna Polihros ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

[2014] Susanna Polihros ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii BATH, CITY UNDER SIEGE: ARCHITECTURE STRUGGLING TO REMAIN WED TO NATURE By SUSANNA POLIHROS A thesis submitted to the Graduate School – New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History written under the direction of Dr. Tod Marder and approved by Dr. Katharine Woodhouse-Beyer Dr. Archer St. Clair-Harvey _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2014 iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS: Bath, City Under Siege: Architecture Struggling to Remain Wed to Nature By SUSANNA POLIHROS Thesis Director: Dr. Tod Marder This thesis examines current historic preservation and conservation efforts for Bath, England’s only complete UNESCO World Heritage city, where urban and commercial development remain a controversial threat to its status. This is best represented by the opposing views of the Bath Preservation Trust and the Bath & North East Somerset Council. While the Trust stands as a supporter of saving Georgian Bath, the Council continues to sacrifice precious greenbelt areas and historic buildings for the purpose of attracting tourists and prospective residents. Both organizations are extensively examined in order to better comprehend Bath’s future. Although no definite answer can be reached at this point in time, besides establishing balance between old and new architecture, examining social and political issues in this city demonstrates that there is a serious need for legal intervention to prevent further destruction to a past way of life so that the modern world can emerge. Areas explored include the conserved Roman Baths, the recent developments of SouthGate and the Western Riverside Development, the conserved Beckford’s Tower and the demolished Gasholder. -

Ms Kate Coggins Sent Via Email To: Request-713266

Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Ms Kate Coggins Date: 8th January 2021 Your Ref: Our Ref: FIDP/015776-20 Sent via email to: Enquiries to: Customer Relations request-713266- Tel: (01454) 868009 [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dear Ms Coggins, RE: FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT REQUEST Thank you for your request for information received on 16th December 2020. Further to our acknowledgement of 18th December 2020, I am writing to provide the Council’s response to your enquiry. This is provided at the end of this letter. I trust that your questions have been satisfactorily answered. If you have any questions about this response, then please contact me again via [email protected] or at the address below. If you are not happy with this response you have the right to request an internal review by emailing [email protected]. Please quote the reference number above when contacting the Council again. If you remain dissatisfied with the outcome of the internal review you may apply directly to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The ICO can be contacted at: The Information Commissioner’s Office, Wycliffe House, Water Lane, Wilmslow, Cheshire, SK9 5AF or via their website at www.ico.org.uk Yours sincerely, Chris Gillett Private Sector Housing Manager cc CECR – Freedom of Information South Gloucestershire Council, Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Department Customer Relations, PO Box 1953, Bristol, BS37 0DB www.southglos.gov.uk FOI request reference: FIDP/015776-20 Request Title: List of Licensed HMOs in Bristol area Date received: 16th December 2020 Service areas: Housing Date responded: 8th January 2021 FOI Request Questions I would be grateful if you would supply a list of addresses for current HMO licensed properties in the Bristol area including the name(s) and correspondence address(es) for the owners. -

Aust Cliff and Manor Farm

This excursion guide is a draft chapter, subject to revision, to be published in a field guide book whose reference is: Lavis, S. (Ed.) 2021. Geology of the Bristol District, Geologists’ Association Guide No. 75. It is not to be circulated or duplicated beyond the instructor and their class. Please send any corrections to Michael Benton at [email protected] Aust Cliff and Manor Farm Michael J. Benton Maps OS Landranger 172 1:50 000 Bristol & Bath Explorer 167 1:25 000 Thornbury, Dursley & Yate BGS Sheet 250 1:50 000 Chepstow Main references Swift & Martill (1999); Allard et al. (2015); Cross et al. (2018). Objectives The purpose of the excursion is to examine a classic section that documents the major environmental shift from terrestrial to marine rocks caused by the Rhaetian transgression, as well as the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, and to sample the rich fossil faunas, and espe- cially the Rhaetian bone beds. Risk analysis Low tides are essential for the excursion to Aust Cliff. Tides rise very rapidly along this section of coast (with a tidal range of about 12 m) and strong currents sweep past the bridge abutment. Visitors should begin the excursion on a falling tide. If caught on the east side of the bridge abutment when the tide rises, visitors should continue east along the coast to the end of the cliff where a path leads back to the motorway service area. In addition, the entire section is a high cliff, and rock falls are frequent, so hard hats must be worn. The Manor Farm section lies inland and is lower, so hard hats are less necessary. -

South Gloucestershire Council Boundary Review Liberal Democrat Group Submission June 2017

South Gloucestershire Council Boundary Review Liberal Democrat Group Submission June 2017 This submission is from the Liberal Democrat group on South Gloucestershire Council. The Lib Dems are the second largest group on the council, and one of only two to ever have had an overall majority. As such, there is a good understanding of community links, and history, across much of the district. In our submission we have focussed upon the areas where we have deep community roots, stretching back over 40 years. In those areas we know the communities well, so feel we can make submissions which reflect the nuances of natural communities. However, there are some areas where we do feel others are better placed to identify the nuances. In those areas we have not sought to offer detailed solutions. We believe communities and individuals in those areas are best placed to provide their local solutions. We have submitted specific plans for the district over the areas where we have a good understanding, and believe our proposals are powerful, rooted in strong community identities, and efficient local government. All of the proposals are within the permissible variance from the new electoral quota with 61 Councillors, and we do not believe this needs to be modified up or down to make the map work. South Gloucestershire elects in an “all-up” manner, which means under Commission guidance, a mixture of 1, 2, and 3 member wards is appropriate, which we have proposed. We have proposed no ‘doughnut’, or detached wards, and many of the proposals allow for the reunification of communities which have previously been separated by imposed political boundaries. -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

NOTICE of ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION South Gloucestershire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes listed below Number of Parish Councillors to Number of Parish Councillors to Parishes Parishes be elected be elected Acton Turville Five Marshfield Nine Almondsbury, Almondsbury Four Oldbury-on-Severn Seven Almondsbury, Compton Two Oldland, Cadbury Heath Seven Almondsbury, Cribbs Causeway Seven Oldland, Longwell Green Seven Alveston Eleven Oldland, Mount Hill One Aust Seven Olveston Nine Badminton Seven Patchway, Callicroft Nine Bitton, North Common Six Patchway, Coniston Six Bitton, Oldland Common Four Pilning & Severn Beach, Pilning Four Bitton, South Four Pilning & Severn Beach, Severn Six Beach Bradley Stoke, North Six Pucklechurch Nine Bradley Stoke, South Seven Rangeworthy Five Bradley Stoke, Stoke Brook Two Rockhampton Five Charfield Nine Siston, Common Three Cold Ashton Five Siston, Rural One Cromhall Seven Siston, Warmley Five Dodington, North East Four Sodbury, North East Five Dodington, North West Eight Sodbury, Old Sodbury Five Dodington, South Three Sodbury, South West Five Downend & Bromley Heath, Downend Ten Stoke Gifford, Central Nine Downend & Bromley Heath, Staple Hill Two Stoke Gifford, University Three Doynton Five Stoke Lodge and the Common Nine Dyrham & Hinton Five Thornbury, Central Three Emersons Green, Badminton Three Thornbury, East Three Emersons Green, Blackhorse Three Thornbury, North East Four Emersons Green, Emersons Green Seven Thornbury, North West Three Emersons Green, Pomphrey Three Thornbury, South Three -

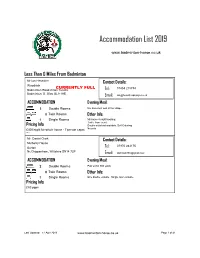

Accommodation List 2019

Accommodation List 2019 www.badminton-horse.co.uk Less Than 0 Miles From Badminton Mr Ian Heseltine Contact Details: Woodside CURRENTLY FULL 01454 218734 Badminton Road Acton Turville Tel: Badminton, S. Glos GL9 1HE Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 3 Double Rooms No. Excellent pub in the village 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 1 Single Rooms Minimum 4 night booking. 1 mile from event Pricing Info: Double sofa bed available. Self Catering £400/night for whole house - 7 person capac No pets. ity Mr. Daniel Clark Contact Details: Mulberry House 07970 283175 Burton Tel: Nr.Chippenham, Wiltshire SN14 7LP Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 2 Double Rooms Pub within 300 yards 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 1 Single Rooms One double ensuite. Single room ensuite. Pricing Info: £50 pppn Last Updated: 12 April 2019 www.badminton-horse.co.uk Page 1 of 41 Ms. Polly Herbert Contact Details: Dairy Cottage 07770 680094 Crosshands Farm Little Sodbury Tel: , South Glos BS37 6RJ Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 2 Double Rooms Optional and by arrangement - pubs nearby Twin Rooms Other Info: Single Rooms Currently full from 2nd-4th May. 1 double ensuite £140 pn - 1 room with dbl & 1/2 singles ensuite - £230 pn. Pricing Info: Other contact numbers: 07787557705, 01454 324729. Min stay 3 nights. £120 per night for double room inc. breakfas Plenty of off road parking. Very quiet locaion. t; "200 per night for 4-person room with full o Transportation Available Mrs. Lynn Robertson Contact Details: Ashlea Lakeside Retreat 07870 686306 Mapleridge Lane Horton Tel: Bristol, BS37 6PW Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 3 Double Rooms 2 Twin Rooms Other Info: 0 Single Rooms 3 x self catering glamping pods -with ensuite shower, underfloor heating etc. -

Gordon Richard Sydney Haines War Time Memories I

Gordon Richard Sydney Haines war time memories I was born in Almondsbury Hospital South Gloucestershire on 23 December, 1932. My parents Florence Mabel HAINES and Sydney George HAINES then lived at Box Tree Cottage in the Village of Alveston, Gloucestershire with my sister Jean, two years older than me and my Grandfather, William Ballinger, Mum’s father. Life at home was pleasant; the village was then small and uncomplicated. An outside bucket toilet, no running water, we had our own well with a small pump, no electricity, we used oil lamps and had a coal-burning indoor stove which also provided hot water for the Saturday night bath ! We grew all our own vegetables and had apple and plum trees, raspberry and gooseberry bushes for all our fruit. The fields around provided us with blackberries and mushrooms and there was a small forest named Wolfridge, where the housing estates now exist, providing firewood and adventures for the village boys. My primary education was at the Church of England Elementary School at Rudgeway a mile away over the fields from Alveston but aged 10 I transferred to Thornbury Council School where I took the examination for entry to Thornbury Grammar School on a local council scholarship, at age 11 in 1943 and in September that year began my secondary education. My sister Jean was also studying there. My earliest recollection of doing something as a family was the requirement at the outbreak of war in 1939 for everyone to register at the local council office (opposite the Cross Hands Hotel !) to be fitted for Gas Masks. -

Land at Cribbs Causeway

1. Welcome January 2014 Today’s Exhibition The Joint Venture This exhibition displays the latest proposals for a mixed-use Land at Cribbs Causeway is a joint venture development on Land at Cribbs Causeway which will be between Skanska & Deeley Freed set up in About Skanska submitted as an outline planning application in February. The 2010. The partnership utilises the strong Skanska is one of the world’s leading proposed development, which forms part of the wider Cribbs / local knowledge and relationships of both construction groups. We carry out all Patchway New Neighbourhood, will include a range of organisations as well as drawing upon the aspects of the construction, development housing, a new primary school, retail and community facilities, significant resources Skanska are investing into and infrastructure process - from financing new public open spaces and woodland planting. Bristol and the South West. projects, through design and construction right through to facilities management, operation Last November stakeholders, near neighbours and the The responsibility of the partnership is to and maintenance. We are currently delivering wider public gave feedback on the emerging proposals. The work with local communities, stakeholders schools and infrastructure projects in the South following boards show how feedback and results of further and partners to maximise the potential of the West, and have three offices in Bristol. site studies have informed the latest draft masterplan. Key site. This will include providing much needed issues raised included concerns around transport, traffic and housing, sporting facilities and recreational access especially in the context of the number of new homes areas, commercial opportunities and public being proposed on this site and coming forward within the infrastructure such as schools and community wider area. -

Norley Cottage, Norley Lane, Tormarton, Badminton

Norley Cottage, Norley Lane, Tormarton, Badminton, Gloucestershire, GL9 1JD Grade II Listed Character Home Sympathetically Refurbished 3 Receptions 4 Bedrooms Home Office & Double Garage Bathroom & En-Suite Large Sunny Gardens 4 The Old School, High Street, Sherston, SN16 0LH Surrounded by countryside James Pyle Ltd trading as James Pyle & Co. Registered in England & Wales No: 08184953 Excellent Road Networks Approximately 0.28 acres Price Guide: £795,000 Approximately 1,688 sq ft ‘Surrounded by farmland on the rural edge of Tormarton village, this characterful Grade II Listed home has been superbly refurbished and is located for convenient access to the M4 corridor’ The Property particular displays the original stone fireplace garage has been split to create an extra secure centres and Bristol International Airport. with original grate and rear ogee-headed storeroom. Norley Cottage is a Grade II Listed period opening mirroring the windows. Off the kitchen Tenure & Services semi-detached house situated down a rural lane there is a useful utility room with rear access. Situation on the outskirts of the village of Tormarton with The kitchen was beautifully refitted just last We understand the property is Freehold with oil excellent access to road networks to the M4, year with double Belfast sink, integral Situated within South Gloucestershire, the fired central heating, mains drainage and water. Bristol and Bath. Surrounded by fields and dishwasher, fridge, oven and oil-fired modern village of Tormarton has a collection of farmland, the property enjoys an excellent 360- Rayburn. Completing the ground floor, there is traditional stone built period houses set within Directions degree outlook over the countryside whilst a downstairs WC off the hallway. -

XXXX Helmet Magazine February 2020

EDITOR’S JOTTINGS St Helen’s Church Alveston Methodist Church www.sthelensalvs.co.uk Once again another month in lockdown has passed, and Rev Simon Edwards 418176 Rev David Moss 415190 although technically and legally things are easing there are Contact Steward still many in our community who don’t feel safe out and Licensed Lay Ministers:- Christine Dugdale 413097 about. So please do continue the good work of passing at Tracey Black 417660 a distance and looking out for your neighbours’ needs. [email protected] Stewards Judith Heybyrne 616725 With this in mind we are still not printing and delivering the PeterJones 412912 ‘Helmet’ and will be reviewing things at the beginning of DoreenStears 850453 Church Wardens:- August to make our decision regarding the September Harry Griffiths 612140 edition. ElaineLee 419322 Views expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the Helmet editors Once we do decide to return to print we will be needing you Children’s activities - or commi�ee. to send in your articles and photos of all the goings on in contact Tracey With thanks to Ken Pearce for the the village so that those who have been shielding without front cover internet access can get to see them. We welcome articles and Advertising Rates This month’s cover is on an optimistic theme of summer sunshine and sports. Having had some lovely weather we news of interest from Per Year - Size Per Issue growers are not going to complain about the rain, and individuals and groups within 10% off the Parish of Alveston. -

WILTSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position WI_AMAV00 SU 15217 41389 UC road AMESBURY Church Street; opp. No. 41 built into & flush with churchyard wall Stonehenge Road; 15m W offield entrance 70m E jcn WI_AMAV01 SU 13865 41907 UC road AMESBURY A303 by the road WI_AMHE02 SU 12300 42270 A344 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due N of monument on the Verge Winterbourne Stoke Down; 60m W of edge Fargo WI_AMHE03 SU 10749 42754 A344 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Plantation on the Verge WI_AMHE05 SU 07967 43180 A344 SHREWTON Rollestone top of hill on narrow Verge WI_AMHE06 SU 06807 43883 A360 SHREWTON Maddington Street, Shrewton by Blind House against wall on Verge WI_AMHE09 SU 02119 43409 B390 CHITTERNE Chitterne Down opp. tank crossing next to tree on Verge WI_AMHE12 ST 97754 43369 B390 CODFORD Codford Down; 100m W of farm track on the Verge WI_AMHE13 ST 96143 43128 B390 UPTON LOVELL Ansty Hill top of hill,100m E of line of trees on Verge WI_AMHE14 ST 94519 42782 B390 KNOOK Knook Camp; 350m E of entrance W Farm Barns on bend on embankment WI_AMWH02 SU 12272 41969 A303 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due S of monument on the Verge WI_AMWH03 SU 10685 41600 A303 WILSFORD CUM LAKE Wilsford Down; 750m E of roundabout 40m W of lay-by on the Verge in front of ditch WI_AMWH05 SU 07482 41028 A303 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Winterbourne Stoke; 70m W jcn B3083 on deep verge WI_AMWH11 ST 990 364 A303 STOCKTON roadside by the road WI_AMWH12 ST 975 356 A303 STOCKTON 400m E of parish boundary with Chilmark by the road WI_AMWH18 ST 8759 3382 A303 EAST KNOYLE 500m E of Willoughby Hedge by the road WI_BADZ08 ST 84885 64890 UC road ATWORTH Cock Road Plantation, Atworth; 225m W farm buildings on the Verge WI_BADZ09 ST 86354 64587 UC road ATWORTH New House Farm; 25m W farmhouse on the Verge Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No.