A. S. Hollis [815] Pf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ovid Book 12.30110457.Pdf

METAMORPHOSES GLOSSARY AND INDEX The index that appeared in the print version of this title was intentionally removed from the eBook. Please use the search function on your eReading device to search for terms of interest. For your reference, the terms that ap- pear in the print index are listed below. SINCE THIS index is not intended as a complete mythological dictionary, the explanations given here include only important information not readily available in the text itself. Names in parentheses are alternative Latin names, unless they are preceded by the abbreviation Gr.; Gr. indi- cates the name of the corresponding Greek divinity. The index includes cross-references for all alternative names. ACHAMENIDES. Former follower of Ulysses, rescued by Aeneas ACHELOUS. River god; rival of Hercules for the hand of Deianira ACHILLES. Greek hero of the Trojan War ACIS. Rival of the Cyclops, Polyphemus, for the hand of Galatea ACMON. Follower of Diomedes ACOETES. A faithful devotee of Bacchus ACTAEON ADONIS. Son of Myrrha, by her father Cinyras; loved by Venus AEACUS. King of Aegina; after death he became one of the three judges of the dead in the lower world AEGEUS. King of Athens; father of Theseus AENEAS. Trojan warrior; son of Anchises and Venus; sea-faring survivor of the Trojan War, he eventually landed in Latium, helped found Rome AESACUS. Son of Priam and a nymph AESCULAPIUS (Gr. Asclepius). God of medicine and healing; son of Apollo AESON. Father of Jason; made young again by Medea AGAMEMNON. King of Mycenae; commander-in-chief of the Greek forces in the Trojan War AGLAUROS AJAX. -

2013 Virginia Senior Classical League State Finals Certamen Level III NOTE to MODERATORS: in Answers, Information in Parentheses Is Optional Extra Information

2013 Virginia Senior Classical League State Finals Certamen Level III NOTE TO MODERATORS: in answers, information in parentheses is optional extra information. A slash ( / ) indicates an alternate answer. Underlined portions of a longer, narrative answer indicate required information. ROUND ONE 1. TOSSUP: From what Latin noun, with what meaning, do the words ignition and igneous ultimately derive? ANS: IGNIS, FIRE BONUS: From what Latin verb, with what meaning, do the words coherent and adhesion derive? ANS: HAEREŌ, STICK/CLING 2. TOSSUP: According to Livy and Plutarch, what legendary Roman triumphed four times, was dictator five times, was never once consul, was honored with the title “Second Founder of Rome,” and conquered the city of Veii in 396 BC? ANS: (M. FURIUS) CAMILLUS BONUS: Following the victory over Veii, for what accusation did his political adversaries impeach Camillus? ANS: EMBEZZLEMENT 3. TOSSUP: According to Hesiod, what moon titan, the daughter of Ouranos and Gaia, bore Leto from the union with her brother Coeus? ANS: PHOEBE BONUS: According to Hesiod, what Star goddess was also the daughter of Phoebe and Coeus and the mother of Hecate? ANS: Asteria 4. TOSSUP: What fifteen-book work of Ovid ends with the apotheosis of Julius Caesar? ANS: METAMORPHOSES BONUS: What other work of Ovid, consisting of epistolary poems written by mythological heroines, allowed him to claim that he had created a new genre of mythological elegy? ANS: HEROIDES rd 5. TOSSUP: Give the 3 person singular, pluperfect active subjunctive of noceō, nocēre. ANS: NOCUISSET nd BONUS: Now give the 2 person plural present subjunctive of morior, morī. -

Early Mythology Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY EARLY MYTHOLOGY ANCESTRY 1 INTRODUCTION This book covers the earliest history of man and the mythology in some countries. The beginning from Adam and Eve and their descendants is from the Old Testament, but also by several authors and genealogy programs. The age of the persons in the lineages in Genesis is expressed in their “years”, which has little to do with the reality of our 365-day years. I have chosen one such program as a starting point for this book. Several others have been used, and as can be expected, there are a lot of conflicting information, from which I have had to choose as best I can. It is fairly well laid out so the specific information is suitable for print. In addition, the lineage information shown covers the biblical information, fairly close to the Genesis, and it also leads to both to mythical and historical persons in several countries. Where myth turns into history is up to the reader’s imagination. This book lists individuals from Adam and Eve to King Alfred the Great of England. Between these are some mythical figures on which the Greek (similar to Roman) mythology is based beginning with Zeus and the Nordic (Anglo-Saxon) mythology beginning with Odin (Woden). These persons, in their national mythologies, have different ancestors than the biblical ones. More about the Nordic mythology is covered in the “Swedish Royal Ancestry, Book 1”. Of additional interest is the similarity of the initial creation between the Greek and the Finnish mythology in its national Kalevala epos, from which a couple of samples are included here. -

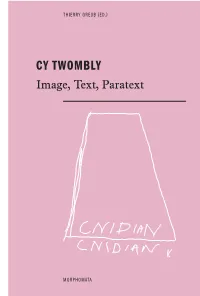

CY TWOMBLY Image, Text, Paratext

THIERRY GREUB (ED.) CY TWOMBLY Image, Text, Paratext MORPHOMATA The artworks of the US artist Cy Twombly (1928–2011) are considered to be hermetic and inaccessible. Pencil scribblings, explosions of paint, tumbling lines, over- lapping layers of color, and inscriptions, geometrical figures, numerals, rows of numbers, words, fragments of quotations, and enigmatic work-titles present very special challenges to both researchers and viewers. In the interdisciplinary and transcultural research meth- od of the Morphomata International Center for Advanced Studies at the University of Cologne, a conference was held in June 2012 that brought art historians together with renowned scholars of Egyptology, Archaeology, German, Greek, English, Japanese, and the Romance languages, i.e. all the fields and cultural spheres that were a source of inspiration for the œuvre of Cy Twombly. While these scholars inquire into the relation between title, work, and inscribed quotations, leading represen- tatives of research on Twombly focus on the visual lan- guage and scriptural-imagistic quality of Cy Twombly’s work. Through comprehensive interpretations of famous single works and groups in all the artistic media employed by Twombly, the volume’s cross-disciplinary view opens up a route into the associative-referential visual language of Cy Twombly. THIERRY GREUB (ED.) – CY TWOMBLY MORPHOMATA EDITED BY GÜNTER BLAMBERGER AND DIETRICH BOSCHUNG VOLUME 37 EDITED BY THIERRY GREUB CY TWOMBLY Image, Text, Paratext WILHELM FINK English edition translated from the German original: Cy Twombly. Bild, Text, Paratext (Morphomata, vol. 13). Paderborn 2014 (based on a conference held at the University of Cologne, 13–15 June 2012, by Morphomata International Center for Advanced Studies) Translated by Orla Mulholland, Daniel Mufson, Ehren Fordyce, and Timothy Murray Translated and printed with the generous support of the Cy Twombly Founda tion, Rome / New York and the Fondazione Nicola Del Roscio, Gaeta unter dem Förderkennzeichen 01UK1505. -

The Abuse of Patriarchal Power in Rome: the Rape Narratives of Ovid’S Metamorphoses

The Abuse of Patriarchal Power in Rome: The Rape Narratives of Ovid’s Metamorphoses A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Classics By K. Tinkler Classics Department University of Canterbury 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Abstract……………….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 CHAPTER ONE: Gender in Rome………………………………………………………………………………………. 12 A Woman’s Place in a Man’s World: Patriarchy in Rome…………………………………………………… 12 Lucretia’s Legacy: The Cultural Template of the Raped Woman……………………………………….. 18 The Intimacy of Rape: The Body of a Woman in Antiquity…………………………………………………. 22 CHAPTER TWO: Rape in the Metamorphoses…………………………………………………………………… 29 The Rape Stories of the Metamorphoses………………………………………………………………………….. 29 The Characteristics of Ovid’s Perpetrators………………………………………………………………………… 30 Gods and Non-Human Perpetrators………………………………………………………………………………….. 34 The Characteristics of Ovid’s Victims…………………………………………………………………………………. 40 The Rape of Philomela………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 44 The Male Gaze………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 48 CHAPTER THREE: The Aftermath of Rape…………………………………………………………………………. 55 The Non-Metamorphic Consequences………………………………………………………………………………. 55 The Psychological Effect on the Victim……………………………………………………………………………… 60 The Eternal Link between the Victim and the Rapist…………………………………………………………. 63 The Second Rape: The Goddesses’ Wrath…………………………………………………………………………. -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

Greek Mythology Link (Complete Collection)

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • Español • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. This PDF contains portions of the Greek Mythology Link COMPLETE COLLECTION, version 0906. In this sample most links will not work. THE COMPLETE GREEK MYTHOLOGY LINK COLLECTION (digital edition) includes: 1. Two fully linked, bookmarked, and easy to print PDF files (1809 A4 pages), including: a. The full version of the Genealogical Guide (not on line) and every page-numbered docu- ment detailed in the Contents. b. 119 Charts (genealogical and contextual) and 5 Maps. 2. Thousands of images organized in albums are included in this package. The contents of this sample is copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. To buy this collection, visit Editions. Greek Mythology Link Contents The Greek Mythology Link is a collection of myths retold by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology, published in 1993 (available at Amazon). The mythical accounts are based exclusively on ancient sources. Address: www.maicar.com About, Email. Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. ISBN 978-91-976473-9-7 Contents VIII Divinities 1476 Major Divinities 1477 Page Immortals 1480 I Abbreviations 2 Other deities 1486 II Dictionaries 4 IX Miscellanea Genealogical Guide (6520 entries) 5 Three Main Ancestors 1489 Geographical Reference (1184) 500 Robe & Necklace of -

Mythology Heroes

Mythology Heroes Trojan Warriors Paris Paris was the son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy, who eloped with Helen, queen of Sparta, thus causing the events that led to the Trojan War. Before he was born, Hecuba saw a dream in which her child was a flaming torch. The explanation to the dream that was given by the seer Aesacus was that the yet unborn child would be the doom of Troy. Aesacus also said on the day of Paris' birth that a child born of royals that day should be killed in order to save the kingdom. However, Priam and Hecuba could not kill their baby son, and instead gave the baby to a herdsman so that he would do the deed. The herdsman, also unable to kill the baby, left him to die on Mount Ida, but the boy was saved by drinking milk from a female bear. When the herdsman returned nine days later, he found the baby still alive and took him back to Troy. While growing up, Paris met the nymph Oenone, and they became lovers; after he left her for Helen, Oenone told him that she would be happy to treat all of his injuries, small or serious, whenever he was wounded. Years later, a magnificent ceremony took place on Mount Olympus for the marriage of Peleus and Thetis. Major and minor deities had been invited, except Eris, the goddess of strife. In retribution, Eris decided to cause havoc, by throwing the Golden Apple of Discord amidst the goddesses, which was inscribed with the words "To the fairest". -

Cy Twombly Bild, Text, Paratext

THIERRY GREUB (HRSG.) CY TWOMBLY Bild, Text, Paratext MORPHOMATA Die Bildwerke des US-amerikanischen Künstlers Cy Twombly (1928–2011) gelten als her me tisch und schwer zugänglich. Bleistiftgekritzel, Farb ballungen, taumelnde Linien, einander überlagernde Farbschichten und Ein- schreibungen, geometrische Figu ren, Zahlen, Zahlen- reihen, Wörter, Zitatfragmente und rätselhafte Bildtitel stellen Forscher wie Betrachter vor ganz besondere Herausforderungen. Gemäß der interdisziplinär-transkulturellen Forschungs- methode des Internationalen Kollegs Morphomata an der Universität zu Köln versammelte im Juni 2012 ein Kon- gress neben Kunsthistorikern auch namhafte Fachleute aus den Bereichen Ägyptologie, Archäologie, Germanis- tik, Gräzistik, Anglistik, Japanologie und Romanistik, d.h. all jenen Fachgebieten und Kulturkreisen, die eine Inspirationsquelle für das Œuvre Cy Twomblys dar- stellten. Befragen diese den Bezug zwischen Werktitel, Werk und eingeschriebenen Zitaten, so legen führende Vertreter der Twomblyforschung den Fokus auf Bild- sprache und Schriftbildlichkeit bei Cy Twombly. Durch umfassende Deutungen berühmter Einzelwerke und Werkgruppen in sämtlichen von Twombly ange- wandten künstlerischen Medien erschließt der Band in einem fächerübergreifenden Blick einen Zugang zur assoziativ-referentiellen Bildsprache Cy Twomblys. GREUB (HRSG.) – YCY TWOMBL MORPHOMATA HERAUSGEGEBEN VON GÜNTER BLAMBERGER UND DIETRICH BOSCHUNG BAND 13 HERAUSGEGEBEN VON THIERRY GREUB CY TWOMBLY Bild, Text, Paratext WILHELM FINK unter dem Förderkennzeichen 01UK0905. -

Metamorphoses

Dictynna Revue de poétique latine 17 | 2020 Varia Noua … corpora: New Bodies and Gendered Patterns in the Metamorphoses Alison Sharrock Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/dictynna/2277 DOI: 10.4000/dictynna.2277 ISSN: 1765-3142 Publisher Université de Lille Electronic reference Alison Sharrock, “Noua … corpora: New Bodies and Gendered Patterns in the Metamorphoses”, Dictynna [Online], 17 | 2020, Online since 17 December 2020, connection on 14 June 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/dictynna/2277 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/dictynna.2277 This text was automatically generated on 14 June 2021. Les contenus des la revue Dictynna sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Noua … corpora: New Bodies and Gendered Patterns in the Metamorphoses 1 Noua … corpora: New Bodies and Gendered Patterns in the Metamorphoses Alison Sharrock ‘We will argue that, even in the realm of seemingly unconstrained fantasy, not everything is equally likely. In fantasy, any transformation of one kind into another can be imagined. Still, some transformations may be favored over others as they adapt to, and hence reflect, properties of conceptual structure.’ Kelly and Keil (1985) 404 1 Tales of metamorphosis are stories of similarity and affinity as much as they are about change and alterity. Metamorphic continuity is well established as a feature of the Ovidian world, from the ferocity of Lycaon-wolf to the beauty of Daphne-laurel -

Divine Genealogies: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology

Divine Genealogies: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology E. Edward Garvin, Editor ©2015 What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

Scene 1: the Trojan Palace

Scene 1: The Trojan Palace King Priam, Queen Hecuba, Alexandros (Paris), Aesacus King Priam: Ah Hecuba my queen. You’re looking lovely this morning! Queen Hecuba: Good Morning King Priam, ruler of Troy, one of the most powerful poleis in the world. I do feel good because I’m pregnant again. Of course, you know I have lots of babies: 12 sons and several daughters, or something like that. But then that pales in comparisons to all the children you’ve sired with your various other women! Fifty sons in total!! You are really the man! But I digress. I’m a little tired because last night I had a nightmare. King Prima: A nightmare! Much like my belief in love and women, I’m also a strong believer in the gods and the fact that they speak through dreams. What did you dream of? Queen Hecuba: I dreamed that Troy was burning. King Priam: Ye Gads! I better fetch our local prophet/seer to discover what this can mean. Where is Aesacus? Aesacus: Here Sire! What seems to be the problem? King Priam: My lovely Hecuba, whom you can see is great with child, has had a dream that Troy was burning. Aesacus: Ye Gads! This can only mean one thing, naturally. The child you carry will be the end of Troy. You must destroy it. King Priam: Cool with me. I’ve got sons to spare. Queen Hecuba: Ye Gads! I’m going into labor!! Prince Alexandros: Waa! Waa! I’ve just been born! King Priam: Go figure.