Notes and Comments North Carolina Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2017 Beverage Marketing Directory Copyright Notice

About this demo This demonstration copy of The Beverage Marketing Directory – PDF format is designed to provide an idea of the types and depth of information and features available to you in the full version as well as to give you a feel for navigating through The Directory in this electronic format. Be sure to visit the Features section and use the bookmarks to click through the various sections and of the PDF edition. What the PDF version offers: The PDF version of The Beverage Marketing Directory was designed to look like the traditional print volume, but offer greater electronic functionality. Among its features: · easy electronic navigation via linked bookmarks · the ability to search for a company · ability to visit company websites · send an e-mail by clicking on the link if one is provided Features and functionality are described in greater detail later in this demo. Before you purchase: Please note: The Beverage Marketing Directory in PDF format is NOT a database. You cannot manipulate or add to the information or download company records into spreadsheets, contact management systems or database programs. If you require a database, Beverage Marketing does offer them. Please see www.bmcdirectory.com where you can download a custom database in a format that meets your needs or contact Andrew Standardi at 800-332-6222 ext. 252 or 740-314-8380 ext. 252 for more information. For information on other Beverage Marketing products or services, see our website at www.beveragemarketing.com The 2017 Beverage Marketing Directory Copyright Notice: The information contained in this Directory was extensively researched, edited and verified. -

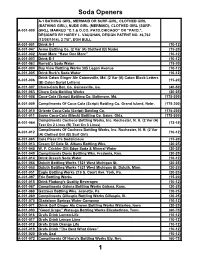

Soda Handbook

Soda Openers A-1 BATHING GIRL, MERMAID OR SURF-GIRL, CLOTHED GIRL (BATHING GIRL), NUDE GIRL (MERMAID), CLOTHED GIRL (SURF- A-001-000 GIRL), MARKED “C.T.& O.CO. PATD.CHICAGO” OR “PATD.”, DESIGNED BY HARRY L. VAUGHAN, DESIGN PATENT NO. 46,762 (12/08/1914), 2 7/8”, DON BULL A-001-001 Drink A-1 (10-12) A-001-047 Acme Bottling Co. (2 Var (A) Clothed (B) Nude) (15-20) A-001-002 Avon More “Have One More” (10-12) A-001-003 Drink B-1 (10-12) A-001-062 Barrett's Soda Water (15-20) A-001-004 Bay View Bottling Works 305 Logan Avenue (10-12) A-001-005 Drink Burk's Soda Water (10-12) Drink Caton Ginger Ale Catonsville, Md. (2 Var (A) Caton Block Letters A-001-006 (15-20) (B) Caton Script Letters) A-001-007 Chero-Cola Bot. Co. Gainesville, Ga. (40-50) A-001-063 Chero Cola Bottling Works (20-25) A-001-008 Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Baltimore, Md. (175-200) A-001-009 Compliments Of Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Grand Island, Nebr. (175-200) A-001-010 Oriente Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. (175-200) A-001-011 Sayre Coca-Cola (Block) Bottling Co. Sayre, Okla. (175-200) Compliments Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var (A) A-001-064 (12-15) Text On 2 Lines (B) Text On 3 Lines) Compliments Of Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var A-001-012 (10-12) (A) Clothed Girl (B) Surf Girl) A-001-065 Cola Pleez It's Sodalicious (15-20) A-001-013 Cream Of Cola St. -

SLEMCO Power July-August 2013

JULY/AUGUST 2013 SLEMCOPOWER ACADIANA’S BREWERS Their recipe for great beer: mix art and passion with hops and grain PAGE 4 ANNUAL MEETING WRAP-UP PAGE 2 PAYING FOR COLLEGE PAGE 7 SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS PAGE 12 PSLEMCO OWER TakeNote Volume 62 No. 4 July/August 2013 The Official Publication of the Southwest Louisiana Electric Membership Corporation 3420 NE Evangeline Thruway P.O. Box 90866 Lafayette, Louisiana 70509 Phone 337-896-5384 www.slemco.com BOARD OF DIRECTORS ACADIA PARISH Bryan G. Leonards, Sr., Secretary-Treasurer Merlin Young NOT YOUR TYPICAL ST. MARTIN PARISH William Huval, First Vice President Adelle Kennison SATURDAY MORNING! LAFAYETTE PARISH Photos by P.C. Piazza Jerry Meaux, President Carl Comeaux t SLEMCO’s June 1 annual meeting, ST. LANDRY PARISH Edna Roger was seated five rows up Leopold Frilot, Sr. from the floor near the stage with Gary G. Soileau A her son Scott Roger, her daughter Connie VERMILION PARISH Hanks and Connie’s husband Tony. Joseph David Simon, Jr., Second Vice President She remembered Scott repeating, Charles Sonnier “We’re not going to win. We’re not going ATTORNEY to win,” to which she kept replying, James J. Davidson, III “You’ve got to have faith!” As the winning card was about to be EXECUTIVE STAFF pulled she stood up. But she quickly sat J.U. Gajan Chief Executive Officer & General Manager back down on hearing the name Edna. As Glenn Tamporello she heard Roger and her street address, Director of Operations she jumped up from her chair and began Jim Laque Director of Engineering waving to the crowd. -

1929 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 1929 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1929 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. - - - - - - - - Price 25 cents FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION EDGAR A. McCULLOCH, Chairman. GARLAND S. FERGUSON, Jr. CHARLES W. HUNT. WILLIAM E. HUMPHREY. CHARLES H. MARCH. OTIS B. JOHNSON, Secretary. CONTENTS PART I. INTRODUCTION Page The Commission as an Aid to Business 4 Investigation of Stock Acquisitions 6 The Year’s Activities 8 Background of the Commission 13 Description of Procedure 17 Publications of the Commission 21 PART II. DIVISIONAL REPORTS Public-utilities investigation (electric power and gas) 26 Trade-practice conferences 30 Introduction 30 Procedure 32 Summary of conferences 34 Barn-equipment industry 34 Beauty and barber supplies 34 Cheese assemblers 35 Cottonseed crushers 36 Cut stone 36 Face brick 37 Fertilizer 38 Grocery 39 Gypsum 40 Jewelry 41 Knit underwear 41 Kraft paper 42 Lime 42 Metal lath 43 Naval stores 43 Paint, varnish, and lacquer 44 Paper board 44 Petroleum 45 Plumbing and heating 46 Plywood 46 Publishers of periodicals 47 Range boiler 48 Rebuilt typewriter (second conference) 49 Reinforcing steel fabricating 49 Scrap iron and steel 50 Spice grinders 51 Steel office furniture 51 Upholstery textile 52 Waxed paper (second conference) 52 Woodworking machinery 53 Woolens and trimmings 54 Special board of investigation (fraudulent advertising) 55 Chief examiner’s division 57 Outline of procedure 57 Expedition -

Appendix B Soft Drinks Bottled and Sold in El Paso 2010 a & W Root

Appendix B Soft Drinks Bottled and Sold in El Paso 2010 A & W Root Beer Magnolia Coca-Cola Bottling Co. (1982-present) Apollinaris Co. Mineral Water G. Edwin Angerstein (1884) Dieter & Sauer (1889) Houck & Dieter (1983-1912) Ayer’s Sarsaparilla Distributor unknown, advertised in El Paso Herald (1893) Barlo (Lime, Grape) Woodlawn Bottling Co. (1919) Barma (Near-beer) Blatz Co. (1918) Barq’s (Root Beer, Grape, Moon-Glo, Imitation Strawberry) Barq’s Bottling Co. (1939-1956) Barq’s Dr. Pepper Bottling Co. (1957-1976) Pepsi Cola Bottling Co. (1988 [possibly earlier]-present) Belfast Type Ginger Ale Empire Bottling Works (1912[?]-1924) Bevo M. Ainsa & Son (1917-1918) James A. Dick Co. (1919-1920) Big Red Dr. Pepper Bottling Co. (1977[?]-1980) Magnolia Coca-Cola Bottling Co. (1980-1985) Kalil Bottlling Co. (1985-present) Blatz (near-beer) Woodlawn Bottling Co. (1920-1930 [?]) Bock (Near-beer) Tri-State Beverage Co. (1919) 655 Bone-Dry (Near-beer) Border Beverage Co. (1920) Botl-o (Grape, Lime) Grapette Bottling Co. (1942-1956, maybe later) Bravo (Near-beer) Tri-State Beverage Co. (1918-1921) Bronco Empire Bottling Works (1919-1922) Empire Link Industries (1923-1925) Empire Products Corporation (1926-1928, possibly 1956) Bubble Up Barq’s Bottling Co. ([?]-1956) Barq’s Dr. Pepper Bottling Co. (1957-1969 [1976?]) possibly Dr. Pepper Bottling Co. (1977-1980) Kalil Bottlling Co. (1985-present) Budweiser (near-beer) Empire Bottling Works (1920) El Paso Brewing Assn. (1920) Tri-State Beverage Co. (1921) Buffalo Lithia Water Henry Pfaff (1906, possibly as early as 1900-1907) Southwestern Liquor Co. (1908-1909) Canada Dry Mixers (ginger ale, sparkling water, collins mixer, lime rickey, Quinine Water) Hurd & Butler Distributing Co. -

The Howard Is the Fund Drive Event in the Opening Tomorrow History of Howard IMSO Attend the Rally!

v.32 An Unparalleled The Howard Is The Fund Drive Event In The Opening Tomorrow History Of Howard IMSO Attend The Rally! -FRIDAY, JANUARY 16, 1948 TNO. 11 ig Rally Set Tomorro 4 = “She Ain't What She Used To Bo... > Drive For $2,500 000 Co-op Gets Face - Lifting And ‘New Look” Officially Launched - Features Coke YZ *. BY BOB WEAVER Bar % % Fie News Editor And More Space “Make Mine A Coke’ . The Birmingham-Southern-Howard College Joint Appeal | officially begins tomorrow night when supporters of the two ORO. | ‘By John Stokes denominational institutions will meet at 7:30 at the Birming-{ | Remember the banging, buzzing ham Municipal Auditorium for a mass civic rally. sounds and the pungent odor which Bishop Arthur Moore, president of the Methodist Board | prevailed on the campus during fi- Missions, and Dr. Duke McCall, executive secretary of the nal exam week? Executive Board of the South- The sounds came from the ham- ern Baptist Convention, will be mers and saws of workmen and the the principal speakers. Enrollment | odor came, not from the coffee urn One million dollars has been but from varnish and paint. As a set as the Jefferson County result of this activity which was goal in the state-wide cam- Hits 1243 ¢ terminated during the holidays, paign which is expected to net $2,- Howard College students now have 500,000 for the two schools. Sub- a new and improved co-op. About scriptions to the drive will be pay- 80% Are Veterans the only things which look the same able over a period of three years. -

The History and Bottles of the Soft Drink Industry in El Paso, Texas

Bottles on the Border: The History and Bottles of the Soft Drink Industry in El Paso, Texas, 1881-2000 © Bill Lockhart 2010 [Revised Edition – Originally Published Online in 2000] Dedication I wish to dedicate this, my first book, to Dr. David L. Carmichael, of The University of Texas at El Paso for igniting the spark that caused me to become an archaeologist and to Dr. John A. Peterson (also of UTEP) for providing the impetus that lured me into historical archaeology and the study of bottles. Table of Contents Table of Contents.. i Figures. iii Tables.. iv Original Foreword. v 2010 Foreword. viii Acknowledgments. x Chapter 1 – General History of El Paso Bottlers. 1 El Paso Bottlers Association. 5 Chapter 2 – Dating Soft Drink Bottles.. 9 Color. 10 Morphology. 13 Manufacturing Techniques. 17 Manufacturer’s Marks. 23 Volume Labeling. 25 Retailer’s Markings. 25 Stated Dates. 27 Dating Local Bottles. 31 Particular Concerns with Soft Drink Bottles. 35 Applying Dating Techniques. 38 Deposition. 41 Deposition Lag.. 44 Use-Life of Returnable Bottles. 46 Chapter 3 – National Franchisers Represented in El Paso.. 52 The Colas: Coca-Cola. 52 The Colas: Pepsi-Cola. 54 The Colas: Royal Corwn Cola. 55 The Fruit Punch: Dr. Pepper. 56 The Uncola: Seven-Up.. 57 The Mixers: Canada Dry. 58 Chapter 4 – Bottle Descriptions and Photographs. 61 Descriptions. 61 i Descriptions Within the Text.. 62 Photographs. 65 Chapter 5a – Houck & Dieter and Related Companies. 67 A.L. Houck & Co. (1880-1882).. 70 History. 70 Houck & Dieter, El Paso, Texas (1881-1912). 72 History. 72 Eichwald, Lemley, and Heineman. -

Pennsylvania's New Long-Arm Statute: Extended Jurisdiction Over Foreign Corporations

Volume 79 Issue 1 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 79, 1974-1975 10-1-1974 Pennsylvania's New Long-Arm Statute: Extended Jurisdiction Over Foreign Corporations William J. Donohue Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation William J. Donohue, Pennsylvania's New Long-Arm Statute: Extended Jurisdiction Over Foreign Corporations, 79 DICK. L. REV. 51 (1974). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol79/iss1/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PENNSYLVANIA'S NEW LONG-ARM STATUTE: EXTENDED JURISDICTION OVER FOREIGN CORPORATIONS INTRODUCTION In recent years, the Pennsylvania "long-arm" statute has been criticized as an ineffective means of obtaining jurisdiction over a foreign corporation.' The argument most frequently advanced was that the statute, in its original and amended versions, had been so narrowly constructed that the Pennsylvania courts were unable to exercise jurisdiction over a foreign corporation to the fullest ex- tent allowed by the due process clause of the fourteenth amend- ment. This deficiency in the Pennsylvania statute worked a hard- ship upon its citizens, since they were subject to the expense and risk of litigating their claims in another jurisdiction. In an effort to correct this situation, the Pennsylvania legisla- ture has enacted -

The 2018 Beverage Marketing Directory

2018 BMC Beverage Company Database - Print Version 2018 Edition (Published March 2018) more than 1,200 pages, with 14,000+ brands, 19,500+ key executives and 6,500+ beverage companies. Covers the entire United States’ and Canadian beverage industry. For A Full The BMC Beverage Company Database - Print Version is the industry's premier fact-checking and prospecting source book. List of Includes extras such as government and trade associations and Available industry supplier listings, plus a 14,000+ brand index. Databases, Go To BMCCompanyDB.com INSIDE: AVAILABLE FORMAT & SAMPLE PAGES PRICING Samples of this publication’s contents, data and layout. 2 Print Version $1,550 To learn more, to place an advance order or to inquire about additional user licenses call: Andrew Standardi +1 740.314.8380 ext. 252 [email protected] HAVE Contact Andrew Standardi: (U.S. only) 800-332-6222 x 252 or ? QUESTIONS? 740-314-8380 x 252 [email protected] Beverage Marketing Corporation 143 Canton Road, 2nd Floor, Wintersville, OH 43953 Tel: 800-332-6222 | 740-314-8380 Fax: 740-314-8639 About this demo This demonstration copy of The BMC Beverage Company Database – PDF format is designed to provide an idea of the types and depth of information and features available to you in the full version as well as to give you a feel for navigating through The Database in this electronic format. Be sure to visit the Features section and use the bookmarks to click through the various sections of the PDF edition. What the PDF version offers: The PDF version of The BMC Beverage Company Database was designed to look like the traditional print volume, but offer greater electronic functionality. -

ML032480723.Pdf

WM DOCKET CONTROL CENTER *85 JUN -7 Al1: 3 9 DEPARTMENTOF ENGERY & TRANSPORTATION Watkins Building, 510 George Street Jackson, Mississippi 39202-3096 601t961-4733 June 4, 1985 Ms. Donna R. Mattson Section Leader Division of Waste Management Office of Nuclear Material Safety and Safeguards U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Washington, D.C. 20555 Dear Ms. Mattson: As per your telephone conversation with Kelly Haggard of my staff, I have enclosed copies of the additional information we have provided the Department of Energy on the Environmental Assessments. Enclosed are the following: 1. "Fifty Golden Years", Richton Baptist Church, Richton, Mississippi, 1906-1956, Church history booklet. 2. "First Baptist Church", Richton, Mississippi, 1906-1981, Seventy-five years anniversary booklet. 3. "Richton, Mississippi - Comprehensive Plan - A Guide for Community Growth". 1974. South Mississippi Planning and Development District. (This plan has never been implemented due to the repository program.) 4. "Richton .......Remembered and Retold", 1976, Authored by Mrs. Josie Pleasant Smollen Wilson. 5. Memo about recent seismic lines including oil company contact. 6. Memo about current drilling activity including oil company contact. 7. Memo about location of acid bogs. We will continue to provide you with any additional information or comments we transmit to DOE. 9506250005 850604 PDR WASTE pDR W,-16PDR Ms. Donna R. Mattson June 4, 1985 Page Two Thank you for your interest and I look forward to continuing the good communication flow we have with NRC. Sincerely yours, John W. Green Interim Director JWG :hpf Enclosures cy: Mr. Roger Gale, wo enclosures Richton Baptist Church , Richton Miss 1906-1956 PASTORS OF RICHTON BAPTIST CHURCH R. -

Cristina M. Almanza, MBA

Cristina M. Almanza, MBA, APR Marketing | PR | Graphic Design + Trilingual Buffalo Rock Company Business Development Coordinator — Birmingham Division | Birmingham, AL September 2017 – Present Support the growth of beverage business for the 5 county area of: Jefferson, Blount, Shelby, St. Clair, and Walker Counties. • Generated 140 new accounts within 3 years including the central bar at Pizitz building, Rev Birmingham’s Reveal Kitchen Food Stall, and nine locations at Pizitiz Food Hall. Jacksonville State University • Increased Hispanic market revenue growth by 356.6% from 2015 to 2017. Secured and Bachelors of Fine Arts (BFA) coordinated new community events including Hispanic Independence Day (4,000+ Graphic Design – April 2005 attendance) and Birmingham Taco Fest (4,000+ attendance). Summa Cum Laude • Supervise drink distribution and sales for over 80 events including Birmingham Corporate Masters of Business Administration Challenge and Frog Festival. (MBA) April 2007 • Health ambassador for OT-90 pilot program 2016 – 2017. The program was such a Emory University success that Buffalo Rock Company (BRC) has now a full-time wellness coach. Web Design & Organized 3 BRC Blood Drives. Development Certificates 2013 Business Development Coordinator | Social Media Specialist October 2015 – September 2017 APR Accredited in Public Relations (APR) • Oversaw social media for BRC, Buffalo Rock Ginger Ale, Grapico, and Sunfresh. Increased Twitter presence for @Buffalo_Rock by 43%. Worked with BRC’s legal affairs Public Relations Society of America to procure @Grapico Instagram and Twitter handles from 2 non-related entities. (PRSA) – October 2015 Cristina Almanza, LLC Owner | Anniston, AL September 2012 – Present Marketing, Graphic Design, Hispanic Marketing, and Social Media Strategies. Customers include City of Birmingham, Rubio Law Firm, and Falcon Ministries. -

Table of Cases

TABLE OF CASES Adams Express Co. v. Ohio State Caflisch v. Clymer Power Corpo- Auditor ............... 842, 844, 846 ration ........................ Ader v. Blan ................... 86 Cahan v. Empire Trust Co ...... Adkins v. Children's Hospital..442, 449 854, 855, Adriatic, The .................. 166 Cammack v. Slattery & Bro., Inc. Agnello v. United States ..... 617, 618 Campbell v. Holt ... 478, 48b, 482, Alabama Great Southern R. R. v. Carlisle v. Frears .............. Carroll ....................... 403 Carter, In re ................... Alexander v. Fleming ........... 885 Case of Monopolies ............ Allyn v. Mather ................ 585 Central Transportation Co. v. Alpha Portland Cement Co. v. Pullman Palace Car Co ....... Massachusetts ................ 852 Chaplin v. Smith ............... I American Eagle Fire Ins. Co. v. Chelentis v. Luckenbach Steam- New Jersey Ins. Co ........... 106 ship Co. ................. Ames v. Union Pacific R. R .... 820 Chespeake & Potomac Tel. Co, v. Anglo Patagonian, The ... 406, 407 W hitman ..................... Anway v. Grand Rapids Ry..... 473 Cheung Sum Shee et al. v. Nagle. Aquitania, The ............... 414, 425 Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Patti Archer's Case .................. 583 Ry. v. Minnesota .......... Ashbury Railway Carriage & Iron Chicago Ry. v. Schendel ...... 1 Co. v. Riche ................. 22 Chrysler Sales Corp. v. Smith.,, Asylum of St. Vincent de Paul v. Chrysler Sales Corp. v. Spencer.. McGuire ...................... 92 Cia. Minera Ygnacio Rodriguez Attorney General v. Cook ...... 1015 Ramos, S. A. v. Bartlesville Attualila, The .................. 166 Zinc Co. ..................... City of Rockford v. Rockford Bailly v. Betti ................. 498 Electric Co ................... Baker v. Druesedow ............ 846 Cleveland, etc., Ry. v. Backus..844, Ballard v. Ballard .............. 788 Clifton Shirting Co. v. Bronne Baltic Mining Co. v. Massachu- Shirt Co . .................... setts ......................... 849 Coats v. Town of Stanton .....