'Peter's People'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BT Consultation Listings October 2020 Provisional View Spreadsheet.Xlsx

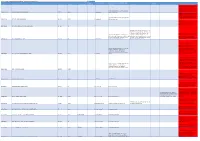

2020 BT Listings - Phonebox Removal Consultation - Provisional View October 2020 Calls Average Name of Town/Parish Details of TC/PC response 2016/2019/2020 Kiosk to be Tel_No Address Post_Code Kiosk Type Conservation Area? monthly calls Council Consultations PC COMMENTS adopted? Additional responses to consultation SC Provisional Comments 2020/2021 SC interim view to object to removal of telephony and kiosk on the following grounds: concerns over mobile phone Object to removal. Poor mobile signal, popular coverage; high numbers of visitors; rural 01584841214 PCO PCO1 DIDDLEBURY CRAVEN ARMS SY7 9DH KX100 0 Diddlebury PC with tourists/walkers. isolation. SC interim view to object to removal of telephony and kiosk on the following grounds: concerns over mobile phone Object to removal. Poor mobile signal, popular coverage; high numbers of visitors; rural 01584841246 PCO1 BOULDON CRAVEN ARMS SY7 9DP KX100 0 Diddlebury PC with tourists/walkers. isolation. SC interim view to Object to removal of telephony and kiosk on the following grounds: rural isolation; concerns over 01584856310 PCO PCO1 VERNOLDS COMMON CRAVEN ARMS SY7 9LP K6 0 Stanton Lacy PC No comments made mobile phone coverage. Culmington Parish Council discussed this matter at their last meeting on the 8th September 2020 and decided to object to the removal of the SC interim view to object to the removal Object. Recently repaired and cleaned. Poor payphone on the following grounds; 'Poor and endorse local views for its retention mobile phone signal in the area as well as having mobile phone signal in the area as well as having due to social need; emergency usage; a couple of caravan sites. -

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-58131-8 - Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales 1300–1500: Volume II: East Anglia, Central England, and Wales Anthony Emery Table of Contents More information CONTENTS Acknowledgements page xii List of abbreviations xiv Introduction 1 PART I EAST ANGLIA 1 East Anglia: historical background 9 Norfolk 9 / Suffolk 12 / Essex 14 / The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 15 / Cambridgeshire 16 / Late medieval art in East Anglia 16 2 East Anglia: architectural introduction 19 Castles 19 / Fortified houses 20 / Stone houses 21 / Timber- framed houses 22 / Brick houses 25 / Monastic foundations 29 / Collegiate foundations 30 / Moated sites 31 3 Monastic residential survivals 35 4 East Anglia: bibliography 45 5 East Anglia: survey 48 Abington Pigotts, Downhall Manor 48 / Baconsthorpe Castle 49 / Burwell Lodging Range 50 / Bury St Edmunds, Abbot’s House 51 / Butley Priory and Suffolk monastic gatehouses 53 / Caister Castle 56 / Cambridge, Corpus Christi College and the early development of the University 61 / Cambridge, The King’s Hall 65 / Cambridge, Queens’ College and other fifteenth century University foundations 68 / Carrow Priory 73 / Castle Acre, Prior’s Lodging 74 / Chesterton Tower 77 / Clare, Prior’s Lodging 78 / Claxton Castle 79 / Denny Abbey 80 / Downham Palace 83 / East Raynham Old Hall and other displaced Norfolk houses 84 / Elsing Hall 86 / Ely, Bishop’s Palace 89 / Ely, Prior’s House and Guest Halls 90 / Ely, Priory Gate 96 / Faulkbourne Hall 96 / Framsden Hall 100 / Giffords Hall 102 / Gifford’s Hall -

Hopton Court “

HOPTON COURT “ Hopton Court was everything we wanted for our wedding and more. “ David and June ABOUT HOPTON COURT Hopton Court sits discreetly on the edge of the beautiful hamlet of Hopton Wafers, between Ludlow and Kidderminster. Set in parkland, amidst 1800 acres of beautiful Shropshire countryside, there are spectacular views from the house and gardens. The house dates from 1776 and is attributed to the architect John Nash, whilst Humphry Repton was responsible for laying out the beautiful grounds and parkland. Hopton Court is unique in its location and in the desire of the owners, Chris and Sarah Woodward, to make it a very special place for you to celebrate your wedding day. We offer a unique country house setting which is exclusively yours and we will tailor make your day to your individual requirements. HOPTON COURT WEDDINGS AT HOPTON COURT Hopton Court will be exclusively yours on your wedding day because we want you to feel completely at home at this beautiful Shropshire country house. With the help of our excellent caterers, we will help you to create the perfect wedding at Hopton Court and can offer advice and all sorts of interesting and unusual ideas to make your day really special. The spectacular conservatory, which holds up to 100 guests, is licensed for civil ceremonies. The Victorian Conservatory is planted with scented, flowering plants and shrubs and is situated in the rose garden. Drinks and canapés can be served on the lawn after the ceremony. Alternatively the Coach House is licensed for up to 60 guests. Alternatively, of course, you may decide to get married in a local Church and hold your reception at Hopton Court afterwards. -

Wem and Surrounding Area Place Plan 2019/20

Wem and Surrounding Area Place Plan 2019/20 1 Contents Context What is a Place Plan? 3 Section 1 List of Projects 5 1.1 Data and information review 1.2 Prioritisation of projects 1.3 Projects for Wem and Surrounding Area Place Plan Section 2 Planning in Shropshire 18 2.1 County-wide planning processes 2.2 This Place Plan area in the county-wide plan Section 3 More about this area 23 3.1 Place Plan boundaries 3.2 Pen picture of the area 3.3 List of Parishes and Elected Members 3.4 Other local plans Section 4 Reviewing the Place Plan 26 4.1 Previous reviews 4.2 Future reviews Annexe 1 Supporting information 28 2 Context: what is a Place Plan? Shropshire Council is working to make Shropshire a great place to live, learn, work, and visit- we want to innovate to thrive. To make that ambition a reality, we need to understand what our towns and communities need in order to make them better places for all. Our Place Plans – of which there are 18 across the county – paint a picture of each local area, and help all of us to shape and improve our communities. Place Plans are therefore documents which bring together information about a defined area. The information that they contain is focussed on infrastructure needs, such as roads, transport facilities, flood defences, schools and educational facilities, medical facilities, sporting and recreational facilities, and open spaces. They also include other information which can help us to understand local needs and to make decisions. -

1 Clerk: Mrs Penny Brasenell, 13 Rorrington,Chirbury

Clerk: Mrs Penny Brasenell, 13 Rorrington,Chirbury,SY156BX Email: [email protected] Phone 0333 006 2010 Website: ludfordshropshire.org.uk Minutes for the Parish Council Meeting of Ludford Parish Council held at the Ludlow Mascall Centre, Lower Galdeford Ludlow on Monday 21st January 2019 Present: Cllr I Liddle Cllr S Liddle Cllr Nick Young, Cllr Paul Knill Cllr Jeff Garraway In attendance Penny Brasenell Parish Clerk. 18.88 Apologies – Cllr Shirley Salmon and Cllr Viv Parry (Shropshire) 18.89 Declarations of Interest – None 18.90 Public Open Session – Nothing to minute as no members of the public present 18.91 No reports from Shropshire Councillors 18.92 Minutes signed and approved from the meetings held on 24th September 2018 18.93 Matters arising from the minutes – The Sheet traffic issues – Clerk to email John Eaton about the success of the recent police speed enforcement Co-Option – Clerk to produce a flyer to be delivered specifically to The Sheet looking to recruit a new Councillor Update from The Chair and Cllrs Garraway and Young on the Emergency Plan Agreed to put detail onto the LPC Website as soon as possible. 18.94 Planning Comments on new applications 18/05791/LBC LPC support this application however would request that a full inspection of the trees overhanging the entire length of the Ludford Hall wall between Ledwyche House and the wooded area and for any remedial tree works to be carried out at the same time. 19/00196/FUL LPC cannot understand from the design and access statement what the main purpose of the extension is. -

By Bicycle … a Four-Day Circular Ride Through Some Of

By bicycle … A four-day circular ride through some of Britain’s scenic green hills and quiet lanes … Page 1 of 12 A: Shrewsbury B: Lyth Hill C: Snailbeach D: The Devil’s Chair (The Stiperstones) E: Mitchell’s Fold (Stapeley Hill) F: Church Stoke G: Stokesay Castle H: Norton Camp J: The Butts (Bromfield) K: Stoke St. Milborough L: Wilderhope Manor M: Church Stretton N: Longnor O: Wroxeter Roman City P: The Wrekin R: Child’s Ercall S: Hawkstone Park T: Colemere V: Ellesmere W: Old Oswestry X: Oswestry Y: St. Winifred’s Well Z: Nesscliffe Day One From Shrewsbury to Bridges Youth Hostel or Bishop’s Castle Via Lead Mines, Snailbeach and the Stiperstones (17 miles) or with optional route via Stapeley Hill and Mitchells Fold (37 miles). The land of the hero, Wild Edric, the Devil and Mitchell, the wicked witch. Day Two From Bridges Youth Hostel or Bishop’s Castle to Church Stretton or Wilderhope Youth Hostel Via Stokesay Castle, Norton Camp, The Butts, Stoke St. Milborough (maximum 47 miles). Giants, Robin Hood and a Saint Day Three From Wilderhope Youth Hostel or Church Stretton to Wem Via Longnor, Wroxeter Roman City, The Wrekin, Childs Ercall, and Hawkstone Park (maximum 48 miles) Ghosts, sparrows and King Arthur, a mermaid and more giants. Day Four From Wem to Shrewsbury Via Colemere, Ellesmere, Old Oswestry, St. Oswald’s Well, St. Winifred’s Well, Nesscliffe and Montford Bridge. (total max. 44 miles) Lots of water, two wells and a highwayman The cycle route was devised by local CTC member, Rose Hardy. -

Middleton Scriven

Sources for MIDDLETON SCRIVEN This guide gives a brief introduction to the variety of sources available for the parish of Middleton Scriven at Shropshire Archives. Printed books:. General works - These may also be available at Bridgnorth library • Eyton, Antiquities of Shropshire • Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society • Shropshire Magazine • Trade Directories which give a history of the town, main occupants and businesses, 1828-1941 • Victoria County History of Shropshire – Volume X • Parish Packs • Maps • Monumental Inscriptions Small selection of more specific books (search www.shropshirearchives.org.uk for a more comprehensive list) • C61 Baldwin of Middleton Scriven – In Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society, vol 1V, 1914, miscellanea ppii-iii • C64 Reading Room Antiquities of Shropshire, Vol. 1 – R Eyton St John The Baptist church, Middleton Scriven, 6009/137 Sources on microfiche or film: Parish and non-conformist church registers Baptisms Marriages / Banns Burials St John the Baptist 1728-1812 1728-1837 / 1754-1811 1728-1812 Methodist records – see Methodist Circuit Records (Reader’s Ticket needed) Up to 1900, registers are on www.findmypast.co.uk Census returns 1841, 1851(indexed), 1861, 1871, 1881 (searchable database on CDROM), 1891 and 1901. Census returns for England and Wales can be looked at on the Ancestry website on the computers, 1841-1911 Maps Ordnance Survey maps 25” to the mile and 6 “to the mile, c1880, c1901 (OS reference: old series LXVI.7 new series SO 6887) Tithe map of c 1840 and apportionment (list of owners/occupiers) Newspapers Shrewsbury Chronicle, 1772 onwards Shropshire Star, 1964 onwards Archives: To see these sources you need a Shropshire Archives Reader's Ticket. -

Yew Trees, Aston Munslow

10 Corvedale Road Craven Arms Shropshire SY7 9ND www.samuelwood.co.uk Yew Trees, Aston Munslow Nr Craven Arms, Shropshire, SY7 9ER A detached bungalow nicely positioned on the edge of a popular village in the Corvedale with accommodation briefly comprising: Reception hall, living room with open fire, kitchen/diner, 2 double bedrooms and bathroom. the property benefits from oil central heating and outside there are lawned gardens, paved terrace, trees and shrubs, driveway parking and a lovely outlook over open farmland. Available to let unfurnished on an Assured Shorthold Tenancy. EPC Rating: F. Application Fees: Single Application £195 (inclusive of VAT) Joint Application £235 (inclusive of VAT) Guarantor Application (if required) £40 (inclusive of VAT) Rent: £695 Per Calendar Month t: 01588 672728 e: [email protected] 10 Corvedale Road, Craven Arms, Shropshire, SY7 9ND Officesoffices At at ShrewsburyShrewsbury ~ ~Church Craven Stretton Arms ~ ~ Ludlow Ludlow Oswestry ~ Church Stretton ~ MayfairMayfair Office, Office, London London www.samuelwood.co.uk This two bedroomed detached bungalow is located within the Conservation Area in this popular village in the Corvedale with facilities that include an excellent Public House, The Swan, and a Shop and Petrol Station. Aston Munslow is a small village about 6 miles east of Craven Arms, with Ludlow around 9 miles distant. The village is situated on the B4368 and offers easy access to Telford and the M54, as well as to the West Midlands. The whole is more particularly described as follows: A glazed door opens into Reception Hall With access to roof space with retractable roof ladder, coving and airing cupboard housing hot water cylinder and shelves Living Room 5.30 x 4.80 (17'5" x 15'9") Having windows to both side and rear elevations with a nice view over the garden and fields. -

Buena Vista, Lower Barns Road

Buena Vista, Lower Barns Road Ludford, Ludlow, Shropshire, SY8 4DS This Detached bungalow sits in ¼ of an acre and is located in a unique position being right on the edge of Ludlow town with the countryside close at hand and offers wonderful potential to renovate and extend or redevelopment of the entire site (all subject to any necessary consents). Currently the accommodation includes: Reception Hall, Living Room, Kitchen / Dining Room, Rear Hallway, Utility Cupboard, Pantry Cupboard, 2 Double Bedrooms, Bathroom, Separate wc and Large Detached Garage. NO onward chain. EPC on order Guide Price: £390,000 t: 01584 875207 e: [email protected] Lower Barns Road is one of Ludlow's most select streets sitting right on the Southern outskirts of the town and the property is South facing. The property offers potential for renovation or redevelopment subject to the necessary consents and its position is somewhat unique being within half a mile of Ludlow's historic town centre yet sits with countryside right at hand. Ludlow is renowned for its architecture, culture and festivals, has a good range of shopping, recreation and educational facilities together with a mainline railway station. The Rear Hallway With door to outside and door into whole is more fully described as follows: good sized utility cupboard with shelves Front door with window to side opens into Bedroom 1 With picture rail and window to side Reception Hall With picture rail, mat well and and 2 small wardrobe cupboards parquet flooring Living Room With windows to front and rear elevations, picture rail and tiled fireplace Bedroom 2 With window to frontage and picture rail Kitchen / Dining Room With 2 windows to rear elevation, base cupboards with stainless steel sink unit, planned space for cooker, space and plumbing for washing machine, room for table and chairs. -

James Perry – a Late Victorian and Edwardian Shropshire Policeman Researched and Written by Andrew Coles

James Perry – A Late Victorian and Edwardian Shropshire Policeman Researched and written by Andrew Coles By the time that James Perry first became a police constable, Shropshire policing had already been established for about 40 years. Administration was split into two, with on the one hand the borough police forces; and on the other the county constabulary. The borough forces were established in the main population areas of Shrewsbury, Bridgnorth, Oswestry and Ludlow. The county constabulary oversaw policing across the rest of the more rural parts of Shropshire. Early Life James Perry was born in 1861, approximately 3 months prior to the 1861 census in the rural parish of Preston Gubbals, a few miles immediately north of Shrewsbury in Shropshire. Since the parish is made of several hamlets, it is unclear exactly which one James was born. Both Bomere Heath and Leaton have claim, but the most likely is Leaton as his baptismal record (13th January 1861) has Leaton as residence. His parents were Jonathan and Ann Perry. Jonathan is listed as a retired soldier on the baptism record, but died around about the same time as James was born, as Ann is a widow by the time of the next census. He had probably been retired for some time as he is listed in the 1851 census as a ‘pensioner agricultural labourer’. By the time of the next census in 1871 Ann Perry was listed as remarried to a John Coldwell in Bomere Heath, and like Jonathan Perry he was also an agricultural labourer. At this point James is at school and how much influence ‘step-father’ John Coldwell had on his future career as he grew up, is impossible to gauge. -

Appeal Decision

Appeal Decision Site visit made on 25 August 2020 by Stuart Willis BA Hons MSc PGCE MRTPI an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State Decision date: 15 September 2020 Appeal Ref: APP/L3245/W/19/3242933 The Sun Inn, B4368 From Pedlars Rest B4365 junction to start of 30mph section Diddlebury, Corfton SY7 9DF • The appeal is made under section 78 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 against a refusal to grant outline planning permission. • The appeal is made by Mr Roger Burgoyne against the decision of Shropshire Council. • The application Ref 18/03863/OUT, dated 17 August 2018, was refused by notice dated 10 October 2019. • The development proposed is erection of detached cottage and garage. Decision 1. The appeal is dismissed. Procedural Matters 2. I have taken the address and description of development above from the application form. While different to those on the decision notice, no confirmation that a change was agreed has been provided to me. 3. Outline planning permission is sought with all matters reserved except for access. I have had regard to the details provided on the Proposed Block Plan (72401/18/03 Rev A) and Street Scene (72401/18/04 Rev A) in relation to this matter and have regarded all other elements as illustrative. I have determined the appeal on this basis. 4. The National Planning Policy Framework (Framework) states that the weight given to relevant policies in emerging plans should be according to their stage of preparation, the extent to which there are unresolved objections to relevant policies and the degree of consistency of the plan with the Framework.