UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ It's Not About

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

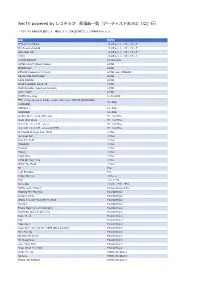

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

The Ends of Aloneness: Scenes of Solitude in Nineteenth-Century Fiction

The Ends of Aloneness: Scenes of Solitude in Nineteenth-Century Fiction By Patricia Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2015 Date of final oral examination: 9/5/2014 This dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Susan D. Bernstein, Professor, English Caroline Levine, Professor, English Mario Ortiz-Robles, Associate Professor, English Theresa Kelley, Professor, English Mary Louise Roberts, Professor, History i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ….................................................................................................................... ii Abstract ….................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction: Negotiating Solitude in the Nineteenth-Century Novel ………………………….. 1 Chapter One: Romantic Aloneness Revisited: Domestic Solitude in Persuasion ...................... 36 Chapter Two: Across the Room, Across the Channel: Villette and Spatial Solitude .................. 68 Chapter Three: Alone Together or Just Alone?: Solitude, The Odd Women, and an Economics of Choice .……………………………………………………………………………...…........ 101 Chapter Four: Money and Mechanization: Institutional Solitude and Counterplots in Our Mutual Friend ………………………………………………………………………………... 131 Coda: What Nineteenth-Century Solitude Tells Us of Perceptions Today ….……………...… 163 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………………………. -

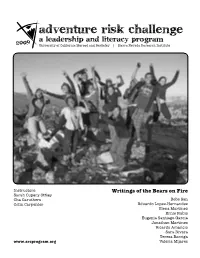

2009 Yosemite Memory Book

adventure risk challenge a leadership and literacy program 2009 University of California Merced and Berkeley | Sierra Nevada Research Institute Instructors: Writings of the Bears on Fire Sarah Cupery Ottley Cha Caruthers Bebe San Colin Carpenter Eduardo Lopez-Hernandez Elena Martinez Ernie Rubio Eugenia Santiago-Garcia Jonathan Martinez Ricardo Amancio Sara Rivera Teresa Barriga www.arcprogram.org Valeria Mijares bebe san My Life I ask myself who I am We do not have food to eat In Asia for fifteen years Lost my friends, community Never knew my life Spread across the world Would evolve so drastically Motherland Ripped apart The first day in America I never give up IOM bags on my hands Like a river never stops The IRC took us to an apartment Like a blessing from God Five years to become US citizen God provides new community I am an immigrant in California I start my new life Arnold says California is My family hopes for me Emergency State To become a helper I live in Oakland I help immigrant students Tough city of gangsters Tutoring and translating I live on High Street Summer search is like water One day Plant my life near the river Four police were killed Now I can grow like a tree I heard it Always be green The gunshots Boom boom boom boom The water woke me up Still echoing through my ears Helped me to find the ARC We planted the trees Which allows me To remember the four police To learn Be a strong leader The same day Work in a diverse community My classmate’s father A Latino My voice represents my life Was killed Who knows We didn’t do anything One day When brown skinned people are killed I can be the one No one cares To change community Change my world Who we are We are Karen people I ask myself who am I Others know we are refugees Create goals We do not have jobs Breathe and learn We do not speak English Thank God for everything 2 ARC Summer 2009 the forest because when I was three the shadows and saw the trees and the A Big Change years old I had to run away from the wildflowers. -

Washburn County)

Kark's Canoeing and Kayaking Guide to 309 Wisconsin Streams By Richard Kark May 2015 Introduction A Badger Stream Love Affair My fascination with rivers started near my hometown of Osage, Iowa on the Cedar River. High school buddies and I fished the river and canoe-camped along its lovely limestone bluffs. In 1969 I graduated from St. Olaf College in Minnesota and soon paddled my first Wisconsin stream. With my college sweetheart I spent three days and two nights canoe-camping from Taylors Falls to Stillwater on the St. Croix River. “Sweet Caroline” by Neil Diamond blared from our transistor radio as we floated this lovely stream which was designated a National Wild and Scenic River in 1968. Little did I know I would eventually explore more than 300 other Wisconsin streams. In the late 1970s I was preoccupied by my medical studies in Milwaukee but did find the time to explore some rivers. I recall canoeing the Oconto, Chippewa, Kickapoo, “Illinois Fox,” and West Twin Rivers during those years. Several of us traveled to the Peshtigo River and rafted “Roaring Rapids” with a commercial company. At the time I could not imagine riding this torrent in a canoe. We also rafted Piers Gorge on the Menomonee River. Our guide failed to avoid Volkswagen Rock over Mishicot Falls. We flipped and I experienced the second worst “swim” of my life. Was I deterred from whitewater? Just the opposite, it seems. By the late 1970s I was a practicing physician, but I found time for Wisconsin rivers. In 1979 I signed up for the tandem whitewater clinic run by the River Touring Section of the Sierra Club’s John Muir Chapter. -

Private TCO Rev 20 Dated 9-15-2019 FINAL.Pub

UNIVERSITY of DUBUQUE PRIVATE PILOT TRAINING COURSE OUTLINE UNIVERSITY of DUBUQUE PRIVATE PILOT TRAINING COURSE OUTLINE University of Dubuque / Private Pilot Certification Training Course Outline / Original 05-31-2002 / Page 1 University of Dubuque / Private Pilo DubuquePrivate University of / UNIVERSITY of DUBUQUE This is to certify that t Certification TrainingOu Course is enrolled in the FAA approved PRIVATE PILOT CERTIFICATION COURSE conducted at the University of Dubuque School #GV8S178Q tline / Original 05-31-2002Originaltline / /Page2 Enrollment Date Primary Flight Instructor Chief Flight Instructor PRIVATE PILOT CERTIFICATION COURSE STUDENT FLIGHT RECORD FTN # University of Dubuque / 2000 University Ave / Dubuque, IA 52001 AIR AGENCY CERTIFICATE NO. GV8S178Q Pilot ’ s Legal Name _____________________________________ SODA DOB_________________ Pilot ’ s Official Signature _____________________________________ CITIZENSHIP I certify that _________________________________ has presented to me a _________________________ ( C ertified Birth Certificate or U.S. Passport ) , establishing that he / she is a U.S. Citizen or national in accordance with 49 CFR 1552.3 ( h ) . Instructor _____________________________________ Date ________________ Cert.# _________________________ Exp. ____________________ PERMANENT ADDRESS Street __________________________________ City ____________________ State_________ Zip________ Phone: Home _____________________ Cell ______________________ ENROLLMENT Date of Enrollment ________________ Date Completed ________________ -

Negli Ultimi Trent'anni, La Disuguaglianza È Aumentata in Molti

CAPITOLO 4 4 DISUGUAGLIANZE, EQUITÀ E SERVIZI AI CITTADINI egli ultimi trent’anni, la disuguaglianza è aumentata in molti paesi avanzati, ivi compresa l’Italia. Peraltro, per i 27 membri Ndell’Unione Europea (con poche eccezioni) sembra sussistere una relazione positiva fra equità e crescita. Il sistema delle imposte sui redditi italiano, pur basato su criteri di equità, subisce alcune distorsioni derivanti dall’insieme degli sgravi e agevolazioni previsto dalla normativa, che è divenuto negli anni molto eterogeneo, finendo per determinare una sorta di “personalizzazione” dell’imposta. Naturalmente, l’equità non va misurata unicamente in termini di distribuzione del reddito, ma soprattutto rispetto alle opportunità che vengono offerte dal sistema socio-economico. Purtroppo, anche da questo punto di vista l’Italia, pur avendo registrato un’alta mobilità assoluta, è tuttora un paese caratterizzato da scarsa fluidità: ad esempio, il sistema di istruzione, che dovrebbe essere lo strumento principale per sostenere la mobilità sociale, offre migliori opportunità ai figli delle classi superiori. Disuguaglianze persistono anche all’interno della famiglia: la distribuzione dei ruoli economici e la ripartizione del lavoro di cura sono, nel nostro Paese, ancora squilibrate a sfavore delle donne: ciò influenza la partecipazione femminile al mercato del lavoro e, quindi, la distribuzione dei redditi. Queste differenze si riflettono anche in molti aspetti della vita dei cittadini: la qualità della salute individuale è influenzata, in modo diretto o indiretto, dal livello socio-economico di appartenenza, poiché a maggiori redditi e a più elevati livelli di istruzione si associa una più alta speranza di vita. Disparità di rilievo si rinvengono, inoltre, in conseguenza dell’appartenenza ad una specifica area territoriale, anche per la disponibilità e la qualità dei servizi pubblici. -

Special Supplement

SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT WeSTORIES OF FLIGHT All IN EVERY KIND OF AIRCRAFTFly AIRSPACEMAG.COM AIR & SPACE We All Fly Reader’s Stories Directory PLEASE TAP ON NAME TO JUMP TO STORY DOMINY, ALAN MOYER, ROBERT SQUIERS, BRUCE A DUNLOP, PHIL I MOYER, ROBERT F. STAATS, BERNEY V. ABEL, GLENN ICKLER, GLENN MUELLER, ROBERT C. STAFFORD, WAYNE ABLETT, KENNETH E MUNKS, JEFFREY STALLBAUMER, STAN ACKERMAN, ALBERT EASTEP, LES J STEED, MIKE ALEXANDER, PETE EIMSTAD, BILL JOHN, KEN N STEINBREUGGE, DAVE ALVAREZ, ALEX ERENSTEIN, ROBERT JONAS, DICK STOLZBERG, MARK AMES, JERRY ERICKSON, GREG JONES, KEITH O STONER, JESSE ANDRÉ, GEORGE M. EVANOFF, MARK O’DONNELL, KEVIN SYLVESTER-GRAY, EWY, RODGER K OLSON, RUSS ELIZABETH B KADUK, JOHN BAIR, BOB F KAISER, TERRY K. P T BATES, TOM FABER, JAMES A. KELLY, CHUCK PAYNTER, JON TAGGART, RALPH E. BEJSOVEC, JOE FERRELL, JACK KENNER, KERRY AND PEARCE, DAVID TARSA, MICHAEL LINDA BENDER, WILLIAM G. FISHBURN, DONN PEPPERS, GARY L. TARWATER, TERRY KIMME, BRUCE E. BENNETT, MARK FLING, JIM PITTMAN, HARRY B. THAYER, BILL KIRBY, HAROLD BENNETT, RICHARD FOREMAN, CHARLES PLANTE, PETE THOMAS, BARRY KNOWLES, ROBERT H. BOLES, F. CLARK FORREST, BUD PRANGE, SHARI THOMAS, BILL KOSTA, MICHAEL BOLES, F. CLARK FOSTER, RAYMOND F. PRATHER, COY THOMPSON, DOUGLAS KRAUSE, ROGER L. ALAN BRADBURY, RAY R. II FREEMAN, VAREL PRZEDPELSKI, ZYGMUNT KUSTERER, ROBERT TWA, GORDON J. BRADFORD, ERNEST FREEMAN, VAREL BRANCIAROLI, MARK FREEZER, DENNY Q BRAYTON, DEAN FRERET, RENÉ J. L U LAFOND, ANDY R UNDERWOOD, WOODY BROOKS, STEVEN FREY, MARK LAGASSE, BOB REYNOLDS, JAMES BRYANT, JAMES M. FUHS, ALLEN E. REYNOLDS, JAMES BURDA, RON LASSERS, GENE V RHODES, CHARLES BUSH, MICHAEL G LAZIER, PHIL VAN HEST, CHRIS LEKWA, STEVE RISELEY, GERALD VIETINGHOFF, WILLIAM GAINES, ROBBY LOCK, FRANK RITTLER, GARY VOGE, TODD A C GAUTHIER, TOM LORDAHL, RICHARD L. -

Animagazin 3. Sz. (2019. Május 19.)

Ismert előadók híresebb dalai - 1. Írta: Edina holmes Mi is az a K-pop? IV. rendezvény k-pop 113 Mostantól pár lapszám erejéig megismerhe- titek a k-pop dalok színe-javát az első generációtól mostanáig. De hogy minél változatosabb legyen a dolog, nemcsak egy generációt veszünk végig egy cikkben, hanem az összesből szemezgetünk időre- ndi sorrendben. Vágjunk is bele! A dalokat meghallgathatjátok az edinaholmes. com-on előadók szerinti lejátszólistákban. H.O.T RAIN TVXQ Tagok száma: 5 Aktív évek: 2002 - napjainkig Tagok száma: Eredetileg öten voltak, K-pop cikksorozat Aktív évek: 1996-2001 Ügynökség: R.A.I.N Company jelenleg ketten vannak. az AniMagazin hasábjain! Ügynökség: SM Entertainment Híresebb dalai: Aktív évek: 2003 - napjainkig Híresebb dalaik: Candy, I Yah, Outside Castle, Bad Guy, It’s Raining, Rainism, Love Song, Ügynökség: SM Entertainment Ha érdekel a k-pop és többet szeretnél We Are The Future, Warrior’s Descendant, Hip Song, 30 sexy, LA song, Gang Híresebb dalaik: Hug, Rising Sun, Balloons, megtudni róla, akkor töltsd le az AniMa- Full of Happiness Mirotic, Wrong Number, Keep Your Head Down, gazin számait és olvasd el cikksorozatunk Catch Me, Something, The Chance of Love korábbi részeit is. Csak kattints az adott cikk címére és máris töltheted az adott számot. Mi is az a K-pop? III. K-pop dalok és albumok Mi is az a K-pop? II. A K-pop rajongói tábor BoA Mi is az a K-pop? Fin.K.L Aktív évek: 2000 - napjainkig Brown Eyed Girls Tagok száma: 4 Ügynökség: SM Entertainment Tagok száma: 4 fő A cikksorozat tovább folytatódik az Ani- Aktív évek: 1998-2005 Híresebb dalai: ID; Peace B, No. -

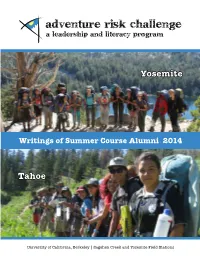

2014 Memory Book

adventure risk challenge a leadership and literacy program Yosemite Writings of Summer Course Alumni 2014 Alondra Chavez Daniel Ortiz David Jung Evelyn Lopez Tahoe Haley Liu Jose Gonzalez Kim Mai Paulina Mosqueda Gonzalez Ronaldo Amaya University of California, Berkeley | Sagehen Creek and Yosemite Field Stations Andrea Bravo Hebert Cisneros Anh Phan Karla Hernandez Cazandra Rangel Santiago Espinoza Christine Kuang Tam Nguyen TAHOE PARTICIPANTS Eduardo Barrera Tristan Deatherage TAHOE - PAGE 3 YOSEMITE - PAGE 25 Adriana Meza Lemus Emma Ponce Alondra Juarez Enrique Guzman Anadi Zuniga Imelda Malaca Brandon Estrada Kwok Man Hou Carla Martinez Lievin Oyumbu YOSEMITE PARTICIPANTS Diego Villareal Valeria Garcia 2 ARC Summer 2014 tahoe BASECAMP LOCATION: Sagehen Creek Field Station, Truckee, CA COURSE LENGTH: 23 days TEAM NAME: J.G.F.F. (Jiātíng, Gia đình, Familia, Familia) Anna Greenberg Melissa Hoffman Salvador Meza Lemus INSTRUCTORS Sean McAlindin ARC Summer 2014 3 andrea bravo Sequoia Who can I trust? Now I am learning to extend my branches How can I trust? Towards my ARC family Baby Sequoia tree in an enormous layer of mist JGFF Confused and unknowing Gia-Ting Strong Sierra Nevada redwood tree Yeh-den withstanding -25 degrees and wild fires Familia Vigorous thunderstorms Family My mother and father were the ominous clouds I am a giving Sequoia ready to strike with thunder Providing shade Insults and punches roared, as thunder and lightning I CAN TRUST Who can I trust? I CAN TRUST How can I trust? I CAN TRUST Even though lightning struck -

2HEART Tell Me Why 2NE1 Falling in Love 2NE1 Clap Your Hands

K-Pop # 2HEART Tell Me Why 2NE1 Falling In Love 2NE1 Clap Your Hands 2NE1 Come Back Home 2NE1 Crush 2NE1 Gotta Be You 2NE1 If I Were You 2NE1 Missing You 2PM Game Over 2PM Go Crazy 2Yoon 24:7 4K Rocking Girl 4MEN Erase 4MEN Propose Song 4MINUTE Hate 4MINUTE Is It Poppin' 4Minute Volumen Up 4MINUTE Whatcha Doin' Today 4MINUTE What's Your Name 9MUSES GUN 100% Guy Like Me 100% Want U Back A AA Call After School Flashback After School First Love Ailee Heaven Ailee I Will Show You Ailee Scandal Ailee U&I A-JAX 2MYX A-JAX HOT GAME Akdong Musician 200% Akdong Musician Eyes, Nose, Lips Akdong Musician Give Love Akdong Musician Melted Ali Don't Act Countrified Ali Eraser Ali I'll Be Damned AOA Confused AOA Elvis AOA BLACK MOYA A-PINK Fairytale Love A-PINK Hush A-PINK I Dont know A-PINK Mr Chu A-PINK My My A-PINK NoNoNo A-PINK Remember April Dream Candy Ateez Illusion B B.A.P. 1004 B.A.P. BADMAN B.A.P. Coffee Shop B.A.P. COMA B.A.P. Crash B.A.P. Hurricane K-Pop 1 / 10 B.A.P. NO MERCY B.A.P. One Shot B.A.P. POWER B.A.P. PUNCH B.A.P. Rain Sound B.A.P. Stop It B.A.P. Unbreakable B.A.P. Warrior B1A4 Baby I'm Sorry B1A4 Beautiful Target B1A4 O.K. B1A4 Solo Day B1A4 Sweet Girl B1A4 What's Happening BabySoul No Better Than Strangers Baekhyun Bambi Baekhyun Like Rain, Like Music Bang Yong Gook I Remember Bang Yong Guk & ZELO Never Give Up BB. -

Woman Hiking Solo: Finding a Personal Connection with Nature

ABSTRACT WOMAN HIKING SOLO: FINDING A PERSONAL CONNECTION WITH NATURE Blending personal narratives and critical theory, this thesis explores a female connection with nature that is marginalized in modern society. The focus begins with a personal account, examining the difficulties of hiking solo as a woman, and how the social constrictions of our culture has made it difficult to do so. Subsequent chapters draw on Cheryl Strayed’s Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail, exposing the challenges of being a woman alone in nature and the benefits of hiking solo. Through an ecofeminist lens, Wild reveals a deeper female connection that harkens back to pre-Christian archetypes of Mother Earth and how revisiting these connections enrich the life of a woman. This thesis also explores a posthumanist approach. The trail itself holds an intrinsic value that acts upon Strayed and helps her to find a personal connection with nature, resulting in a resolution of critical crises in her life. Because American Nature Writing holds a history of male explorers and theorists, this thesis considers a woman’s perspective, what has been left out of the conversation and why, all to better connect with nature and respect our most sacred space. Wendy Anne Batey May 2018 WOMAN HIKING SOLO: FINDING A PERSONAL CONNECTION WITH NATURE by Wendy Anne Batey A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English in the College of Arts and Humanities California State University, Fresno May 2018 APPROVED For the Department of English: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

Lista De Músicas

Lista de músicas Animes: 07 Ghost - Aka no Kakera 07 Ghost - Hitomi no Kotae 11eyes - Arrival of Tears 21 Emon - Beethoven da ne Rock'n'Roll 2x2 Shinobuden - Kurukururin 2x2 Shinobuden - Shinobu sanjou! Aa! Megamisama - Anata no Birthday Aa! Megamisama - Congratulations! Aa! Megamisama - Fortune Smiled on You Aa! Megamisama - Hanabira no Kioku Aa! Megamisama - My Heart Iidasenai, Your Heart Tashikametai Aa! Megamisama - Namida no Imi Aa! Megamisama - Try To Wish Aa! Megamisama Sorezore no Tsubasa - Bokura no Kiseki Aa! Megamisama Sorezore no Tsubasa - Shiawase no Iro Aa! Megamisama TV - Negai Aa! Megamisama TV - OPEN YOUR MIND ~Chiisana Hane Hirogete Aa! Megamisama TV - WING Agatha Christie no Meitantei Poirot to Marple - Lucky Girl ni Hanataba wo Agatha Christie no Meitantei Poirot to Marple - Wasurenaide Ah My Goddess Sorezore no Tsubasa - Congratulations! Ah My Goddess Sorezore no Tsubasa - My Heart Iidasenai, Your Heart Tashikametai Ah My Goddess Sorezore no Tsubasa - Open Your Mind Ai Yori Aoshi - Towa no Hana Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ - Takaramono Air - Nostalgia - Piano Version [Karaoke] Air - Tori no Uta (Karaoke) Air Gear - Chain[Karaoke] Air-Aozora - Piano Version [Karaoke] Akahori Gedou Hour Rabuge - Nesshou!! Rabuge Night Fever [Karaoke] Aldnoah Zero - aLIEz Aldnoah Zero - Heavenly Blue Amagami SS - I Love Amagami SS - Kitto Ashita wa Angel Beats - Brave Song Angel Beats - My Soul Your Beats Angel Heart - Finally Angel Heart -My Destiny Angel Links - All My Soul Angelic Layer - Ame Agari Angelic Layer - The Starry Sky Angelique