A Japanese Local Community in the Aftermath of the Nuclear Accident: Exploring Mothers’ Perspectives and Mechanisms for Dealing with Low-Dose Radiation Exposure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investor Presentation the 28Th Fiscal Period Ended Feb

(TSE code: 8984) Investor Presentation The 28th Fiscal Period Ended Feb. 2020 April 16, 2020 MEMO 1 Table of Contents 1. Financial Results Page Appendix Page Financial Highlights for February 2020 Period 4 Mid-Term Growth Strategy 25 Statement of Income for February 2020 Period 5 Track Record of Asset Size Growth 26 Balance Sheet for February 2020 Period 6 Unit Price Performance 27 Financial Forecasts for Aug. 2020 & Feb. 2021 Periods 7 Acquisitions in April 2020 28-29 Breakdown of DPU Forecast 8 Acquisitions in April 2020 / 30 Acquisitions in February 2020 Period 2. Initiatives to Pursue Growth Leveraging Value Chain of Daiwa House Group 31 Key Financial Indicators 32 Historical Financial Data 33 Overview of Equity Offering in February 2020 10 Historical Portfolio Data 34 Overview of Acquisitions in April 2020 11 Balance Sheets 35 Growth of DPU 12 Statements of Income 36 Pipeline of Daiwa House Group 13 ESG Initiatives 37-41 Market Environment for Logistics Properties 42 3. Operation Status Market Environment for Residential Properties 43 Market Environment for Retail and Hotel Properties 44 Portfolio List 45-48 Portfolio Summary (as of April 3, 2020) 15 Rent Revision Schedule of Logistics Properties 49-51 Operation Status of Logistics Properties 16 Rent Revision Schedule of Retail Properties 52 Operation Status of Residential Properties 17 Appraisal Value Comparison 53-60 Operation Status of Retail and Hotel Properties 18 Unitholder Status 61 Improvement of Portfolio Quality 19 REIT Structure 62 Through Portfolio Rebalancing ESG Initiatives 20 4. Financial Status Financial Status 22-23 2 1. Financial Results Financial Highlights for February 2020 Period DPU Operation Status Financial Status Acquisition 2 properties 6.6 Bn yen Repayment of loans 34.9 Bn yen Sale 5 properties 5.9 Bn yen Refinancing 28.9 Bn yen 6,040 yen Bn yen NOI yield 5.2 % First green bonds 6.0 (Unchanged vs Aug. -

Shiroi Bulletin

SHIROI BULLETIN 白井宣传 白井宣傳 홍보시로이 広報しろい May 2015 五月の鳥 - 燕(つばめ) Swallow PLANETARIUM RENOVATION OPENS ON MAY 2ND (SAT) (プラネタリウムリニューアルオープン) The planetarium in Shiroi city opened in July 1994, and has just been renovated on the 21st anniversary, to a new system of both optical and digital projectors. The optical projector shows the beautiful starry sky with the largest number of 9,500 stars, and digital projector shows the dynamic universe of traveling time and space. A live explanation is always given. For inquiries contact: Planetarium Tel 492-1125 BASIC DESIGN FOR CITY HALL DEVELOPMENT HAS BEEN DECIDED ちょうしゃ せいびきほんせっけい けってい (「庁舎整備基本設計」が決定しました) “Basic Design for Shiroi City Hall Development (draft)” was announced in the Shiroi Bulletin dated February 1. The final report was handed to Mayor Izawa by Umekazu Kawagishi, chairperson of Shiroi City Hall Construction Study Committee, on March 20 after deliberations on the civic explanation and public comment (opinion suggestion). The city, upon being inquired on the policy conference, has now agreed on this report for the “Basic Design for Shiroi City Hall Development”. The future schedule is to develop an implementation design in the fiscal year 2015, a new hall building construction in 2016, and an existing building reduction work of the floor space and improvement work in 2017. However, with consideration of recent uncertainties and changing social situations, such as a further consumption tax increase, increase of various construction costs, etc., the city will aim for an earlier construction order if possible, and reduction of the cost and timeframe. 1 For inquiries contact: Kanzai Keiyaku-ka or Property Management and Contract Section Tel. -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of June, 2009

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of June, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 333 C 25243 ABIKO 5 5 6 7 13 District 333 C 25249 ASAHI 0 0 2 75 77 District 333 C 25254 BOSHUASAI L C 0 0 3 11 14 District 333 C 25257 CHIBA 9 8 9 51 60 District 333 C 25258 CHIBA CHUO 3 3 4 21 25 District 333 C 25259 CHIBA ECHO 0 0 2 24 26 District 333 C 25260 CHIBA KEIYO 0 0 1 19 20 District 333 C 25261 CHOSHI 2 2 1 45 46 District 333 C 25266 FUNABASHI 4 4 5 27 32 District 333 C 25267 FUNABASHI CHUO 5 5 8 56 64 District 333 C 25268 FUNABASHI HIGASHI 0 0 0 23 23 District 333 C 25269 FUTTSU 1 0 1 21 22 District 333 C 25276 ICHIKAWA 0 0 2 36 38 District 333 C 25277 ICHIHARA MINAMI 1 1 0 33 33 District 333 C 25278 ICHIKAWA HIGASHI 0 0 2 14 16 District 333 C 25279 IIOKA 0 0 0 36 36 District 333 C 25282 ICHIHARA 9 9 7 26 33 District 333 C 25292 KAMAGAYA 12 12 13 31 44 District 333 C 25297 KAMOGAWA 0 0 0 37 37 District 333 C 25299 KASHIWA 0 0 4 41 45 District 333 C 25302 BOSO KATSUURA L C 0 0 3 54 57 District 333 C 25303 KOZAKI 0 0 2 25 27 District 333 C 25307 KAZUSA 0 0 1 45 46 District 333 C 25308 KAZUSA ICHINOMIYA L C 0 0 1 26 27 District 333 C 25309 KIMITSU CHUO 0 0 1 18 19 District 333 C 25310 KIMITSU 5 5 14 42 56 District 333 C 25311 KISARAZU CHUO 1 1 5 14 19 District 333 C 25314 KISARAZU 0 0 1 14 15 District 333 C 25316 KISARAZU KINREI 3 3 5 11 16 District 333 C 25330 MATSUDO 0 0 0 27 27 District 333 C 25331 SOBU CHUO L C 0 0 0 39 39 District 333 C -

National Pension

January 2021 NEWSLETTER Published by the City of Inzai 2364-2 Ohmori Inzai City 270 -1396 INZAI ℡ 0476- 42- 5111 Secretarial Public Information Division, Hisho-Koho-ka (TEL: 42-5117) Planning and Policy Division, Kikaku-Seisaku-ka (TEL: 33-4068) This newsletter is published for residents who are not familiar with Japanese language to introduce events designed for residents of Inzai City. Although most programs are basically conducted in Japanese, you are always welcome. Please join our events and enjoy your life in Inzai! 申請手続きはお済みですか ひとり親世帯への臨時特別給付金 Have you already applied for Temporary Special Cash Payments for Single- Parent Households? Application Deadline: February 26 (Fri.), 2021 (postmark deadline) In the case of any single-parent household whose burden of raising any child increases or whose income decreases due to expanding COVID-19, if required, do not forget to apply for the Temporary Special Cash Payments for Single- Parent Households. Amount of Benefits 【Basic Benefits】50,000 yen. In the case of the 2nd child and subsequent child, 30,000 yen in addition per child. *Re-payment (the same amount as the basic benefits) will be done. 【Additional Benefits】50,000 yen per household. Any Persons Requiring Application 【Basic Benefits】 (1) Those whose child rearing allowance for June 2020 was fully suspended due to public pension benefits. (2) Those whose child rearing allowance would be fully/partly suspended for June 2020 due to public pension benefits, even though any application for child rearing allowance has not be done. (3) Those whose family budget changed suddenly due to expanding COVID-19 and the latest income fell to the level eligible for child rearing allowance. -

NEWSLETTER National Health Insurance & National Pension

January 2019 NEWSLETTER Published by the City of Inzai 2364-2 Ohmori Inzai City 270-1396 INZAI ℡ 0476- 42- 5111 Secretarial Public Information Division, Hisho-Koho-ka (TEL: 42-5117) Planning and Policy Division, Kikaku-Seisaku-ka (TEL: 33-4414) This newsletter is published for residents who are not familiar with Japanese language to introduce events designed for residents of Inzai City. Although most programs are basically conducted in Japanese, you are always welcome. Please join our events and enjoy your life in Inzai! Note: The following programs are limited in principle to residents of Inzai City to participate. National Health Insurance & National Pension Enrollment in “National Pension System” When You Turned 20 Years Old “National Pension System” is a public pension system, which all persons aged 20 years or older - less than 60 years (except those who enroll in Welfare Pension System) living in Japan must enroll in. If you fail to submit the notification of enrollment or pay the premiums, you will not be able to receive the national pensions. ◎ Application: Japan Pension Service (Nihon-Nenkin-Kiko) will send a notice of enrollment to you in the previous month of the birth month for 20 years old. Therefore, submit the “Notification of Acquisition of Qualification of Insured Person for National Pension (Kokumin-Nenkin-Hoken-Hihokensha-Shikaku- Shutoku-todokedesho)” to National Health Insurance and National Pension Division (Kokuho-Nenkin-ka) or each branch office. *The enrollment in the “National Pension System” must be started on the previous day of your birthday for 20 years old. Therefore, in the case of being born in April 1, you must enroll in this system on March 31 and pay the premiums for March and thereafter. -

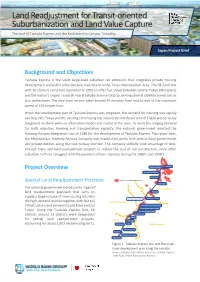

Land Readjustment for Transit-Oriented Suburbanization and Land Value Capture the Case of Tsukuba Express and the Kashiwanoha Campus Township

Land Readjustment for Transit-oriented Suburbanization and Land Value Capture The case of Tsukuba Express and the Kashiwanoha Campus Township Japan Project Brief Background and Objectives Tsukuba Express is the latest large-scale suburban rail extension that integrates private housing development and public infrastructure investment in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. The 58.3-km line with 20 stations came into operation in 2005 to offer fast travel between central Tokyo (Akihabara) and the nation’s largest research hub (Tsukuba Science City) by serving several satellite towns across four prefectures. The new train service takes around 45 minutes from end to end at the maximum speed of 130 km per hour. When the development plan of Tsukuba Express was proposed, the demand for housing was rapidly swelling over Tokyo and the existing commuting line around the northeast area of Tokyo was seriously congested as there were no alternative modes and routes in the area. To meet the surging demand for both suburban housing and transportation capacity, the national government enacted the Housing-Railway Integration Law of 1989 for the development of Tsukuba Express. Two years later, the Metropolitan Intercity Railway Company was established jointly with several local governments and private entities along the new railway corridor. The company skillfully took advantage of zero- interest loans and land readjustment projects to reduce the cost of rail construction, since other suburban rail lines struggled with the payment of loan interests during the 1980’s and 1990’s. Project Overview Kenkyu-gakuen Tsukuba Banpaku-kinenkoen Midorino Special Land Readjustment Practices Major town developmentarea Miraidaira The national government introduced a “special” Ibaragi Prefecture land readjustment approach that aims to Moriya supply a large volume of new housing lots into Kashiwanoha-campus Kashiwa-Tanaka the high-demand market together with fast rail Saitama Prefecture infrastructure and services to and from central Nagareyama-otakanomori Nagareyama-centralpark Tokyo. -

Choshi Geopark and Have Fun.★ Interconnected

“The earth,” A geopark is “living creatures,” where we can Human activity and the “human learn everything History, culture, and industry activity” are Choshi Geopark and have fun.★ interconnected Living creatures Plants and animals The earth Choshi Geoprk related "Exhibitions" Choshi city youth and cultural hall “Choshi Geopark Exhibition room” 【Entrance fee】 free 【Hours】9:00 to 17:00 We will guide you 【Closures】every Monday(except if Monday is a holiday, it will be closed Tuesday.) National holidays(except for May 5th and November 3rd) through the entire park! 1046 Maejuku-cho, Choshi City, Chiba Pref., Japan 〒288-0031 Phone:81-(0)479-24-8911 ※All the fun of Choshi geopark in one place. Horizon Observatory 【Entrance fee】Adult ¥ 380, Elementary and Junior-high school children ¥ 200, Over 65 ¥ 330 【Hours】April to September, 9:00 to 18:30 October to March, 9:00 to 17:00 The last entry is 30 minutes before closing 【Closures】None 1421-1 Tennoudai, Choshi City, Chiba Pref., Japan 〒288-0024 Phone:81-(0)479-25-0930 ※Various fossils and ambers from Choshi can be viewed. Tokawa Mini Furusato Museum 【Entrance fee】free 【Hours】10:30 to 15:30 【Closures】Tuesdays and Wednesdays (except for holidays) Inquiries for Tokawa Mini Furusato Museum “Choshi Tourism Association” office Phone:81-(0)479-22-1544 ※Here, you can find about the history of Tokawa town. You can also view the collection of shellfish fossil researcher, Mr. Tomio Watanabe. Cho-Pi Geo-Cho (Choshi’s publicist) (Choshi Geopark PR ambassador) Editor:The Choshi Geopark Promotion Council office I was born in a cabbage field in Choshi. -

Rocky Inzai) Twin ¥3,900 and up (Tax Included, Ings

20 min. Stop by on your way by express train 60~80by train min. from Narita Airport from Narita Airport from Tokyo Station to Tokyo! INZAI CITY Inzai f lower guide This area boasts flowers of all four seasons This is what the city of Inzai is like Original grilled- by-hand senbei Traditional events rice crackers deeply rooted in the area from ancient times Make the most of your day off Narita Airport — Some fun activities Tokyo INZAI Chiba Pref. Introducing recommended shops Living in Chiba New Town This is what the city of This area boasts flowers of all four seasons Inzai f lower guide Inzai City data 2 As of the end of January 2021 Enjoy flowers during all four seasons that evoke images of Area : 123.79km 2 Cherry is like Total population : 105,843 Inzai's harmonious balance between the city and nature. Inzai Population density : 855 people/km blossom There are various spots around the city where you can Located in northwest Chiba Prefecture, this area can be easily enjoy the seasonal flowers. accessed from downtown Tokyo and Narita Internation- trees al Airport. Incorporating urban and rural features, this city Flowering season: Early to mid-April enables people and nature to co-exist and live in harmony… (* Blossoms are in full bloom only 2–3 days) That is Inzai City. Inzai City Great cherry blossom Mascot character "Inzai-kun" The seal of the Japanese character for "In" is a tree of Yoshitaka trademark of Inzai City. A cosmos, the official About the Symbol flower of the city, is blooming from the tail. -

Advisory Service by Cities

Advisory Service for Foreign Residents as of June 2018 in Chiba City Tel & e-mail Language Day Time Mon(~16:00)・Wed 9:00~16:30 English Tue (~19:30)・Thu・Fri 9:30~16:30 ℡ 043-245-5750 Sat 10:00~16:30 Chiba City ccia@ccia- Mon.・Thu・Fri. 15:00~19:30 Chinese chiba.or.jp Tue・Wed(~19:30)・Sat(.9:30~) 9:00~15:30 Korean Mon.・Thu・Sat. 9:00~15:30 Spanish Tue.・Thu.・(Sat.9:30~16:00) 10:00~16:30 ℡ 047-712-8675 English Mon.~Fri. (Tue・Fri 13:00~) City Hall Chinese Mon.・Wed Spanish 1 ・3・ 5th Thu. Ichikawa City English Mon.~Fri (Wed~20:00) 10:00~17:00 ℡047-712-8675 Gyotoku Chinese Wed Spanish Wed.(1500~20:00), 2・4th Thu. English・Chinese Mon.・Fri. ℡ 047-436-2953 Spanish Funabashi City 10:00~16:00 Korean 2・4th Mon. Portuguese Mon・Fri. (by reservation) English・Chinese 1・3rd Tue. ℡ 047‐366‐1162 9:00~12:00 Matsudo City Spanish・Tagalog 2・4th Tue. Vietnamese 4th Fri. 13:00~16:00 ℡ 04-7167-1133 Chinese Wed.・Fri. Spanish Wed. Kashiwa City 13:00~17:00 English Thu. Korean 2・4th Thu. ℡ 0476-20-1507 English・Chinese Narita City 2・4th Fri. 13:00~16:00 Spanish・Portuguese ℡ 043-484-6326 English・Chinese・ 10:00~12:00 Sakura City Tue・Thu. [email protected] Spanish 13:00~16:00 9:00~12:00 ℡ 0436-23-9866 English Mon.・Thu. Ichihara City 13:00~16:00 ℡ 0436-24-3934 Portuguese 2・4 Thu. -

Financial Results for FY2017

Financial Results for FY2017 May 23, 2018 The 13th Medium Term Management Plan Best Bank 2020 Final Stage - 3 years of value co-creation (Tokyo Stock Exchange First Section: 8331) The 13th Medium Term Management Plan Best Bank 2020 Table of Contents Final FinalStage Stage - 3 years - 3 yearsof value of coco--creationcreation Summary of Financial Results Business Strategies Summary of Financial Results 3 Loans for Corporate Customers (1) 16 Net Interest Income 4 Loans for Corporate Customers (2) 17 Deposit and Loan Portfolios 5 Loans to Real Estate Leasing Sector (1) 18 Securities Portfolio 6 Loans to Real Estate Leasing Sector (2) 19 Net Fees and Commissions Income 7 Housing Loans 20 Expenses 8 Unsecured Consumer Loans 21 Net Credit Costs 9 Group Total Balance of Financial Products 22 Earnings Projections 10 Trust Business and Inheritance-related Services 23 International Business 24 Medium Term Management Plan and Chiba-Musashino Alliance 25 Environment Awareness TSUBASA Alliance 26 Summary of Medium Term Management Plan 12 TSUBASA FinTech Platform 27 Progress toward Numerical Targets in the Plan 13 Economic Environment 14 Initiatives Aimed at Efficiency and Productivity Enhancement Improved Work Efficiency and Personnel Strategy 29 Branch Network Strategy 30 ESG and Capital Policy 31 ESG (1) 32 ESG (2) 33 Capital Policy (1) 34 Capital Policy (2) 35 The 13th Medium Term Management Plan Best Bank 2020 Final Stage - 3 years of value co-creation 1 The 13th Medium Term Management Plan Best Bank 2020 Final FinalStage Stage - 3 years - 3 yearsof -

Chiba Travel

ChibaMeguri_sideB Leisure Shopping Nature History&Festival Tobu Noda Line Travel All Around Chiba ChibaExpressway Joban Travel Map MAP-H MAP-H Noda City Tateyama Family Park Narita Dream Farm MITSUI OUTLET PARK KISARAZU SHISUI PREMIUM OUTLET® MAP-15 MAP-24 Express Tsukuba Isumi Railway Naritasan Shinshoji Temple Noda-shi 18 MAP-1 MAP-2 Kashiwa IC 7 M22 Just within a stone’s throw from Tokyo by the Aqua Line, Nagareyama City Kozaki IC M24 Sawara Nagareyama IC Narita Line 25 Abiko Kozaki Town why don’t you visit and enjoy Chiba. Kashiwa 26 Sawara-katori IC Nagareyama M1 Abiko City Shimosa IC Whether it is for having fun, soak in our rich hot springs, RyutetsuNagareyamaline H 13 Kashiwa City Sakae Town Tobu Noda Line Minami Nagareyama Joban Line satiate your taste bud with superior products from the seas 6 F Narita City Taiei IC Tobu Toll Road Katori City Narita Line Shin-Matsudo Inzai City Taiei JCT Shiroi City Tonosho Town and mountains, Chiba New Town M20 Shin-Yahashira Tokyo Outer Ring Road Higashikanto Expressway Hokuso Line Shibayama Railway Matsudo City Inba-Nichi-idai Narita Sky Access Shin-Kamagaya 24 you can enjoy all in Chiba. Narita Narita Airport Tako Town Tone Kamome Ohashi Toll Road 28 34 Narita IC Musashino Line I Shibayama-Chiyoda Activities such as milking cows or making KamagayaShin Keisei City Line M2 All these conveniences can only be found in Chiba. Naritasan Shinshoji Temple is the main temple Narita International Airport Asahi City butter can be experienced on a daily basis. Narita Line Tomisato IC Ichikawa City Yachiyo City of the Shingon Sect of Chizan-ha Buddhism, Funabashi City Keisei-Sakura Shisui IC You can enjoy gathering poppy , gerbera, Additionally, there are various amusement DATA 398, Nakajima, Kisarazu-City DATA 689 Iizumi, Shisui-Town Sobu LineKeisei-Yawata Shibayama Town M21 Choshi City Isumi and Kominato railroad lines consecutively run across Boso Peninsula, through a historical Choshi 32 and antirrhinum all the year round in the TEL:0438-38-6100 TEL:043-481-6160 which was established in 940. -

Investor Presentation Material

6th Fiscal Period (Fiscal Period Ended July 31, 2019) Investor Presentation Material Mitsui Fudosan Logistics Park Inc. (MFLP-REIT) September 17, 2019 Securities Code 3471 Table of Contents 1. Basic Strategy of MFLP-REIT 4. Market Overview 1-1 Trajectory of Growth of Mitsui Fudosan’s …… P3 4-1 Market Overview …… P27 Logistics Facilities Business 1-2 Four Roadmaps to Stable Growth and …… P4 Trajectory of Growth 5. Appendix 1-3 Steady Implementation of Four Roadmaps …… P5 • Statement of Income and Balance Sheet …… P32 • Individual Property Income Statement …… P33 2. Financial Summary for 6th Fiscal Period • Appraisal Summary for the End of 6th …… P34 2-1 Financial Highlights …… P8 Fiscal Period 2-2 6th Fiscal Period (Ended July 2019) P/L …… P9 • Initiatives for ESG …… P35 2-3 7th Fiscal Period (Ending January 2020) …… P10 • Investment Unit Price Trends/Status of Unitholders …… P38 Earnings Forecast • Mitsui Fudosan’s Major Development/Operation Track Record …… P39 3. Management Status of MFLP-REIT 3-1 Management Status Highlights …… P12 3-2 Our Portfolio …… P13 3-2-1 Location …… P15 3-2-2 Quality …… P17 …… P18 3-2-3 Balance …… P19 3-3 External Growth …… P21 3-4 Internal Growth …… P23 3-5 Financial Strategy …… P25 3-6 Unitholder Relations 1 1. Basic Strategy of MFLP-REIT MFLP-REIT aims to maximize unitholder value through a strategic partnership with Mitsui Fudosan, a major property developer that leverages the comprehensive strengths of its corporate group to create value in its logistics facilities 2 1-1. Trajectory of Growth of Mitsui