Refining the Marine Reptile Turnover at the Early

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resetting the Evolution of Marine Reptiles at the Triassic-Jurassic Boundary

Resetting the evolution of marine reptiles at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary Philippa M. Thorne, Marcello Ruta, and Michael J. Benton1 School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1RJ, United Kingdom Edited by Neil Shubin, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 30, 2011 (received for review December 18, 2010) Ichthyosaurs were important marine predators in the Early Jurassic, life, swimming with lateral undulations of the tail and steering and an abundant and diverse component of Mesozoic marine with elongate fore paddles and producing live young at sea. ecosystems. Despite their ecological importance, however, the After the Tr-J bottleneck, ichthyosaurs apparently did not Early Jurassic species represent a reduced remnant of their former achieve such diversity of form but nonetheless recovered suffi- significance in the Triassic. Ichthyosaurs passed through an evolu- ciently to be the dominant marine predators of the Early Ju- tionary bottleneck at, or close to, the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, rassic, after which they dwindled in diversity through the Middle which reduced their diversity to as few as three or four lineages. and Late Jurassic and much of the Cretaceous until they dis- Diversity bounced back to some extent in the aftermath of the appeared at the end of the Cenomanian, ∼100 Ma, after having end-Triassic mass extinction, but disparity remained at less than had a significant role in Mesozoic seas for 150 Myr. one-tenth of pre-extinction levels, and never recovered. The group In this study, we concentrate on disparity (morphological fi remained at low diversity and disparity for its nal 100 Myr. -

In Pliocene Deposits, Antarctic Continental Margin (ANDRILL 1B Drill Core) Molly F

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln ANDRILL Research and Publications Antarctic Drilling Program 2009 Significance of the Trace Fossil Zoophycos in Pliocene Deposits, Antarctic Continental Margin (ANDRILL 1B Drill Core) Molly F. Miller Vanderbilt University, [email protected] Ellen A. Cowan Appalachian State University, [email protected] Simon H. H. Nielsen Florida State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/andrillrespub Part of the Oceanography Commons, and the Paleobiology Commons Miller, Molly F.; Cowan, Ellen A.; and Nielsen, Simon H. H., "Significance of the Trace Fossil Zoophycos in Pliocene Deposits, Antarctic Continental Margin (ANDRILL 1B Drill Core)" (2009). ANDRILL Research and Publications. 61. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/andrillrespub/61 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Antarctic Drilling Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in ANDRILL Research and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Antarctic Science 21(6) (2009), & Antarctic Science Ltd (2009), pp. 609–618; doi: 10.1017/ s0954102009002041 Copyright © 2009 Cambridge University Press Submitted July 25, 2008, accepted February 9, 2009 Significance of the trace fossil Zoophycos in Pliocene deposits, Antarctic continental margin (ANDRILL 1B drill core) Molly F. Miller,1 Ellen A. Cowan,2 and Simon H.H. Nielsen3 1. Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, USA 2. Department of Geology, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608, USA 3. Antarctic Research Facility, Florida State University, Tallahassee FL 32306-4100, USA Corresponding author — Molly F. -

Cryptoclidid Plesiosaurs (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Upper Jurassic of the Atacama Desert

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujvp20 Cryptoclidid plesiosaurs (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Upper Jurassic of the Atacama Desert Rodrigo A. Otero , Jhonatan Alarcón-Muñoz , Sergio Soto-Acuña , Jennyfer Rojas , Osvaldo Rojas & Héctor Ortíz To cite this article: Rodrigo A. Otero , Jhonatan Alarcón-Muñoz , Sergio Soto-Acuña , Jennyfer Rojas , Osvaldo Rojas & Héctor Ortíz (2020): Cryptoclidid plesiosaurs (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Upper Jurassic of the Atacama Desert, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2020.1764573 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2020.1764573 View supplementary material Published online: 17 Jul 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 153 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ujvp20 Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology e1764573 (14 pages) © by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2020.1764573 ARTICLE CRYPTOCLIDID PLESIOSAURS (SAUROPTERYGIA, PLESIOSAURIA) FROM THE UPPER JURASSIC OF THE ATACAMA DESERT RODRIGO A. OTERO,*,1,2,3 JHONATAN ALARCÓN-MUÑOZ,1 SERGIO SOTO-ACUÑA,1 JENNYFER ROJAS,3 OSVALDO ROJAS,3 and HÉCTOR ORTÍZ4 1Red Paleontológica Universidad de Chile, Laboratorio de Ontogenia y Filogenia, Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Las Palmeras 3425, Santiago, Chile, [email protected]; 2Consultora Paleosuchus Ltda., Huelén 165, Oficina C, Providencia, Santiago, Chile; 3Museo de Historia Natural y Cultural del Desierto de Atacama. Interior Parque El Loa s/n, Calama, Región de Antofagasta, Chile; 4Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas, Universidad de Concepción, Barrio Universitario, Concepción, Región del Bío Bío, Chile ABSTRACT—This study presents the first plesiosaurs recovered from the Jurassic of the Atacama Desert that are informative at the genus level. -

A Mysterious Giant Ichthyosaur from the Lowermost Jurassic of Wales

A mysterious giant ichthyosaur from the lowermost Jurassic of Wales JEREMY E. MARTIN, PEGGY VINCENT, GUILLAUME SUAN, TOM SHARPE, PETER HODGES, MATT WILLIAMS, CINDY HOWELLS, and VALENTIN FISCHER Ichthyosaurs rapidly diversified and colonised a wide range vians may challenge our understanding of their evolutionary of ecological niches during the Early and Middle Triassic history. period, but experienced a major decline in diversity near the Here we describe a radius of exceptional size, collected at end of the Triassic. Timing and causes of this demise and the Penarth on the coast of south Wales near Cardiff, UK. This subsequent rapid radiation of the diverse, but less disparate, specimen is comparable in morphology and size to the radius parvipelvian ichthyosaurs are still unknown, notably be- of shastasaurids, and it is likely that it comes from a strati- cause of inadequate sampling in strata of latest Triassic age. graphic horizon considerably younger than the last definite Here, we describe an exceptionally large radius from Lower occurrence of this family, the middle Norian (Motani 2005), Jurassic deposits at Penarth near Cardiff, south Wales (UK) although remains attributable to shastasaurid-like forms from the morphology of which places it within the giant Triassic the Rhaetian of France were mentioned by Bardet et al. (1999) shastasaurids. A tentative total body size estimate, based on and very recently by Fischer et al. (2014). a regression analysis of various complete ichthyosaur skele- Institutional abbreviations.—BRLSI, Bath Royal Literary tons, yields a value of 12–15 m. The specimen is substantially and Scientific Institution, Bath, UK; NHM, Natural History younger than any previously reported last known occur- Museum, London, UK; NMW, National Museum of Wales, rences of shastasaurids and implies a Lazarus range in the Cardiff, UK; SMNS, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, lowermost Jurassic for this ichthyosaur morphotype. -

A Large Hadrosaurid Dinosaur from Presa San Antonio, Cerro Del Pueblo Formation, Coahuila, Mexico

A large hadrosaurid dinosaur from Presa San Antonio, Cerro del Pueblo Formation, Coahuila, Mexico ROGELIO ANTONIO REYNA-HERNÁNDEZ, HÉCTOR E. RIVERA-SYLVA, LUIS E. SILVA-MARTÍNEZ, and JOSÉ RUBÉN GUZMAN-GUTIÉRREZ Reyna-Hernández, R.A., Rivera-Sylva, H.E., Silva-Martínez, L.E., and Guzman-Gutiérrez, J.R. 2021. A large hadro- saurid dinosaur from Presa San Antonio, Cerro del Pueblo Formation, Coahuila, Mexico. Acta Palae onto logica Polonica 66 (Supplement to x): xxx–xxx. New hadrosaurid postcranial material is reported, collected near Presa San Antonio, Parras de la Fuente municipality, Coahuila, Mexico, in a sedimentary sequence belonging to the upper Campanian of the Cerro del Pueblo Formation, in the Parras Basin. The skeletal remains include partial elements from the pelvic girdle (left ilium, right pubis, ischium, and incomplete sacrum), a distal end of a left femur, almost complete right and left tibiae, right metatarsals II and IV, cervical and caudal vertebrae. Also, partially complete forelimb elements are present, which are still under preparation. The pubis shows characters of the Lambeosaurinae morphotypes, but the lack of cranial elements does not allow us to directly differentiate this specimen from the already described hadrosaurid taxa from the studied area, such as Velafrons coahuilensis, Latirhinus uitstlani, and Kritosaurus navajovius. This specimen, referred as Lambeosaurinae indet., adds to the fossil record of the hadrosaurids in southern Laramidia during the Campanian. Key words: Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae, Lambeosaurinae, Cretaceous, Campanian, Mexico. Rogelio Antonio Reyna-Hernández [[email protected]], Luis E. Silva-Martínez [[email protected]], Laboratorio de Paleobiología, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Av. -

Estimating the Evolutionary Rates in Mosasauroids and Plesiosaurs: Discussion of Niche Occupation in Late Cretaceous Seas

Estimating the evolutionary rates in mosasauroids and plesiosaurs: discussion of niche occupation in Late Cretaceous seas Daniel Madzia1 and Andrea Cau2 1 Department of Evolutionary Paleobiology, Institute of Paleobiology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland 2 Independent, Parma, Italy ABSTRACT Observations of temporal overlap of niche occupation among Late Cretaceous marine amniotes suggest that the rise and diversification of mosasauroid squamates might have been influenced by competition with or disappearance of some plesiosaur taxa. We discuss that hypothesis through comparisons of the rates of morphological evolution of mosasauroids throughout their evolutionary history with those inferred for contemporary plesiosaur clades. We used expanded versions of two species- level phylogenetic datasets of both these groups, updated them with stratigraphic information, and analyzed using the Bayesian inference to estimate the rates of divergence for each clade. The oscillations in evolutionary rates of the mosasauroid and plesiosaur lineages that overlapped in time and space were then used as a baseline for discussion and comparisons of traits that can affect the shape of the niche structures of aquatic amniotes, such as tooth morphologies, body size, swimming abilities, metabolism, and reproduction. Only two groups of plesiosaurs are considered to be possible niche competitors of mosasauroids: the brachauchenine pliosaurids and the polycotylid leptocleidians. However, direct evidence for interactions between mosasauroids and plesiosaurs is scarce and limited only to large mosasauroids as the Submitted 31 July 2019 predators/scavengers and polycotylids as their prey. The first mosasauroids differed Accepted 18 March 2020 from contemporary plesiosaurs in certain aspects of all discussed traits and no evidence Published 13 April 2020 suggests that early representatives of Mosasauroidea diversified after competitions with Corresponding author plesiosaurs. -

Lower Jurassic to Lower Middle Jurassic Succession at Kopy Sołtysie and Płaczliwa Skała in the Eastern Tatra Mts (Western

Volumina Jurassica, 2013, Xi: 19–58 Lower Jurassic to lower Middle Jurassic succession at Kopy Sołtysie and Płaczliwa Skała in the eastern Tatra Mts (Western Carpathians) of Poland and Slovakia: stratigraphy, facies and ammonites Jolanta IWAŃCZUK1, Andrzej IWANOW1, Andrzej WIERZBOWSKI1 Key words: stratigraphy, Lower to Middle Jurassic, ammonites, microfacies, correlations, Tatra Mts, Western Carpathians. Abstract. The Lower Jurassic and the lower part of the Middle Jurassic deposits corresponding to the Sołtysia Marlstone Formation of the Lower Subtatric (Krížna) nappe in the Kopy Sołtysie mountain range of the High Tatra Mts and the Płaczliwa Skała (= Ždziarska Vidla) mountain of the Belianske Tatra Mts in the eastern part of the Tatra Mts in Poland and Slovakia are described. The work concentrates both on their lithological and facies development as well as their ammonite faunal content and their chronostratigraphy. These are basinal de- posits which show the dominant facies of the fleckenkalk-fleckenmergel type and reveal the succession of several palaeontological microfacies types from the spiculite microfacies (Sinemurian–Lower Pliensbachian, but locally also in the Bajocian), up to the radiolarian microfacies (Upper Pliensbachian and Toarcian, Bajocian–Bathonian), and locally the Bositra (filament) microfacies (Bajocian– Bathonian). In addition, there appear intercalations of detrital deposits – both bioclastic limestones and breccias – formed by downslope transport from elevated areas (junction of the Sinemurian and Pliensbachian, Upper Toarcian, and Bajocian). The uppermost Toarcian – lowermost Bajocian interval is represented by marly-shaly deposits with a marked admixture of siliciclastic material. The deposits are correlated with the coeval deposits of the Lower Subtatric nappe of the western part of the Tatra Mts (the Bobrowiec unit), as well as with the autochthonous-parachthonous Hightatric units, but also with those of the Czorsztyn and Niedzica successions of the Pieniny Klippen Belt, in Poland. -

Pluridisciplinary Evidence for Burial for the La Ferrassie 8 Neandertal Child

Pluridisciplinary evidence for burial for the La Ferrassie 8 Neandertal child Balzeau, Antoine; Turq, Alain; Talamo, Sahra; Daujeard, Camille; Guérin, Guillaume; Welker, Frido; Crevecoeur, Isabelle; Fewlass, Helen; Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Lahaye, Christelle; Maureille, Bruno; Meyer, Matthias; Schwab, Catherine; Gómez-Olivencia, Asier Published in: Scientific Reports DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-77611-z Publication date: 2020 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): Balzeau, A., Turq, A., Talamo, S., Daujeard, C., Guérin, G., Welker, F., Crevecoeur, I., Fewlass, H., Hublin, J-J., Lahaye, C., Maureille, B., Meyer, M., Schwab, C., & Gómez-Olivencia, A. (2020). Pluridisciplinary evidence for burial for the La Ferrassie 8 Neandertal child. Scientific Reports, 10(1), [21230]. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598- 020-77611-z Download date: 24. sep.. 2021 www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Pluridisciplinary evidence for burial for the La Ferrassie 8 Neandertal child Antoine Balzeau1,2*, Alain Turq3, Sahra Talamo4,5, Camille Daujeard1, Guillaume Guérin6,7, Frido Welker8,9, Isabelle Crevecoeur10, Helen Fewlass 4, Jean‑Jacques Hublin 4, Christelle Lahaye6, Bruno Maureille10, Matthias Meyer11, Catherine Schwab12 & Asier Gómez‑Olivencia13,14,15* The origin of funerary practices has important implications for the emergence of so‑called modern cognitive capacities and behaviour. We provide new multidisciplinary information on the archaeological context of the La Ferrassie 8 Neandertal skeleton (grand abri of La Ferrassie, Dordogne, France), including geochronological data ‑14C and OSL‑, ZooMS and ancient DNA data, geological and stratigraphic information from the surrounding context, complete taphonomic study of the skeleton and associated remains, spatial information from the 1968–1973 excavations, and new (2014) feldwork data. -

Appendix 3.Pdf

A Geoconservation perspective on the trace fossil record associated with the end – Ordovician mass extinction and glaciation in the Welsh Basin Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Nicholls, Keith H. Citation Nicholls, K. (2019). A Geoconservation perspective on the trace fossil record associated with the end – Ordovician mass extinction and glaciation in the Welsh Basin. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 26/09/2021 02:37:15 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/622234 International Chronostratigraphic Chart v2013/01 Erathem / Era System / Period Quaternary Neogene C e n o z o i c Paleogene Cretaceous M e s o z o i c Jurassic M e s o z o i c Jurassic Triassic Permian Carboniferous P a l Devonian e o z o i c P a l Devonian e o z o i c Silurian Ordovician s a n u a F y r Cambrian a n o i t u l o v E s ' i k s w o Ichnogeneric Diversity k p e 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 S 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 n 23 r e 25 d 27 o 29 M 31 33 35 37 39 T 41 43 i 45 47 m 49 e 51 53 55 57 59 61 63 65 67 69 71 73 75 77 79 81 83 85 87 89 91 93 Number of Ichnogenera (Treatise Part W) Ichnogeneric Diversity 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 n 23 r e 25 d 27 o 29 M 31 33 35 37 39 T 41 43 i 45 47 m 49 e 51 53 55 57 59 61 c i o 63 z 65 o e 67 a l 69 a 71 P 73 75 77 79 81 83 n 85 a i r 87 b 89 m 91 a 93 C Number of Ichnogenera (Treatise Part W) -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

Letter to the Editor

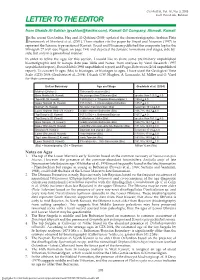

GeoArabia, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2005 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain LETTER TO THE EDITOR from Ghaida Al-Sahlan ([email protected]), Kuwait Oil Company, Ahmadi, Kuwait n the recent GeoArabia, Haq and Al-Qahtani (2005) updated the chronostratigraphic Arabian Plate Iframework of Sharland et al. (2001). These studies cite the paper by Yousif and Nouman (1997) to represent the Jurassic type section of Kuwait. Yousif and Nouman published the composite log for the Minagish-27 well (see Figure on page 194) and depicted the Jurassic formations and stages, side-by- side, but only in a generalized manner. In order to refine the ages for this section, I would like to share some preliminary unpublished biostratigraphic and Sr isotope data (see Table and Notes) from analyses by Varol Research (1997 unpublished report), ExxonMobil (1998 unpublished report) and Fugro-Robertson (2004 unpublished report). To convert Sr ages (Ma) to biostages, or biostages to ages, I have used the Geological Time Scale (GTS) 2004 (Gradstein et al., 2004). I thank G.W. Hughes, A. Lomando, M. Miller and O. Varol for their comments. Unit or Boundary Age and Stage Gradstein et al. (2004) Makhul (Offshore) Tithonian-Berriasian (Bio) Base Makhul (N. Kuwait) No younger than Tithonian (Bio) greater than 145.5 + 4.0 Top Hith (W. Kuwait) 150.0 (Sr) = c. Tithonian/Kimmeridgian ? 150.8 + 4.0 Upper Najmah (S. Kuwait) 155.0 (Sr) = c. Kimmeridgian/Oxfordian 155.7 + 4.0 Najmah (N. Kuwait) No older than Oxfordian (Bio) less than 161.2 + 4.0 Lower Najmah Shale (N. Kuwait) middle and late Bathonian (Bio) 166.7 to 164.7 + 4.0 Top Sargelu (S. -

Mesozoic Marine Reptile Palaeobiogeography in Response to Drifting Plates

ÔØ ÅÒÙ×Ö ÔØ Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates N. Bardet, J. Falconnet, V. Fischer, A. Houssaye, S. Jouve, X. Pereda Suberbiola, A. P´erez-Garc´ıa, J.-C. Rage, P. Vincent PII: S1342-937X(14)00183-X DOI: doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2014.05.005 Reference: GR 1267 To appear in: Gondwana Research Received date: 19 November 2013 Revised date: 6 May 2014 Accepted date: 14 May 2014 Please cite this article as: Bardet, N., Falconnet, J., Fischer, V., Houssaye, A., Jouve, S., Pereda Suberbiola, X., P´erez-Garc´ıa, A., Rage, J.-C., Vincent, P., Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates, Gondwana Research (2014), doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2014.05.005 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates To Alfred Wegener (1880-1930) Bardet N.a*, Falconnet J. a, Fischer V.b, Houssaye A.c, Jouve S.d, Pereda Suberbiola X.e, Pérez-García A.f, Rage J.-C.a and Vincent P.a,g a Sorbonne Universités CR2P, CNRS-MNHN-UPMC, Département Histoire de la Terre, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 38, 57 rue Cuvier,