Conference Paper No.37

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murray Bookchin´S Libertarian Municipalism

CONCEPTOS Y FENÓMENOS FUNDAMENTALES DE NUESTRO TIEMPO UNAM UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES SOCIALES MURRAY BOOKCHIN´S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM JANET BIEHL AGOSTO 2019 1 MURRAY BOOKCHIN’S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM By Janet Biehl The lifelong project of the American social theorist Murray Bookchin (1921–2006) was to try to perpetuate the centuries-old revolutionary socialist tradition. Born to socialist revolutionary parents in the Bronx, New York, he joined the international Communist movement as a Young Pioneer in 1930, then was inducted into the Young Communist League in 1934, where he trained to become a young commissar for the coming proletarian revolution. Impatient with traditional secondary education, he received a thoroughgoing education in Marxism-Leninism at the Workers School in lower Manhattan, where he immersed himself in dialectical materialism and the labor theory of value. But in the summer of 1939, when Stalin’s Soviet Union formed a pact with Nazi Germany, he cut his ties with the party to join the Trotskyists, who expected World War II to end in international proletarian revolution. When the war ended with no such revolution, many radical socialists of his generation abandoned the Left altogether.1 But Bookchin refused to give up on the socialist revolutionary project, or abandon the goal of replacing barbarism with socialism. Instead, in the 1950s, he set out to renovate leftist thought for the current era. He concluded that the new revolutionary arena would be not the factory but the city; that the new revolutionary agent would be not the industrial worker but the citizen; that the basic institution of the new society must be, not the dictatorship of the proletariat, but the citizens’ assembly in a face-to-face democracy; and that the limits of capitalism must be ecological. -

In Pursuit of Freedom, Justice, Dignity, and Democracy

In pursuit of freedom, justice, dignity, and democracy Rojava’s social contract Institutional development in (post) – conflict societies “In establishing this Charter, we declare a political system and civil administration founded upon a social contract that reconciles the rich mosaic of Syria through a transitional phase from dictatorship, civil war and destruction, to a new democratic society where civil life and social justice are preserved”. Wageningen University Social Sciences Group MSc Thesis Sociology of Development and Change Menno Molenveld (880211578090) Supervisor: Dr. Ir. J.P Jongerden Co – Supervisor: Dr. Lotje de Vries 1 | “In pursuit of freedom, justice, dignity, and democracy” – Rojava’s social contract Abstract: Societies recovering from Civil War often re-experience violent conflict within a decade. (1) This thesis provides a taxonomy of the different theories that make a claim on why this happens. (2) These theories provide policy instruments to reduce the risk of recurrence, and I asses under what circumstances they can best be implemented. (3) I zoom in on one policy instrument by doing a case study on institutional development in the north of Syria, where governance has been set – up using a social contract. After discussing social contract theory, text analysis and in depth interviews are used to understand the dynamics of (post) conflict governance in the northern parts of Syria. I describe the functioning of several institutions that have been set –up using a social contract and relate it to “the policy instruments” that can be used to mitigate the risk of conflict recurrence. I conclude that (A) different levels of analysis are needed to understand the dynamics in (the north) of Syria and (B) that the social contract provides mechanisms to prevent further conflict and (C) that in terms of assistance the “quality of life instrument” is best suitable for Rojava. -

Social Ecology and Communalism

Murray Bookchin Bookchin Murray $ 12,95 / £ xx,xx Social Ecology and Communalism Replace this text Murray Bookchin ocial cology Social Ecology and Communalism and Communalism Social Ecology S E and Communalism AK Press Social Ecology and Communalism Murray Bookchin Social Ecology and Communalism Bookchin, Murray Social Ecology and Communalism Library of Congress Control Number 2006933557 ISBN 978-1-904859-49-9 Published by AK Press © Eirik Eiglad and Murray Bookchin 2006 AK Press 674–A 23rd St. Oakland, CA 94612 USA www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press UK PO Box 12766 Edinburgh, EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555–5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] Design and layout by Eirik Eiglad Contents An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism 7 What is Social Ecology? 19 Radical Politics in an Era of Advanced Capitalism 53 The Role of Social Ecology in a Period of Reaction 68 The Communalist Project 77 After Murray Bookchin 117 An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism We are standing at a crucial crossroads. Not only does the age- old “social question” concerning the exploitation of human labor remain unresolved, but the plundering of natural resources has reached a point where humanity is also forced to politically deal with an “ecological question.” Today, we have to make conscious choices about what direction society should take, to properly meet these challenges. At the same time, we see that our very ability to make the necessary choices are being undermined by an incessant centralization of economic and political power. Not only is there a process of centralization in most modern nation states that divests humanity of any control over social affairs, but power is also gradually being transferred to transnational institutions. -

Social Ecology and the Non-Western World

Speech delivered at the conference “Challenging Capitalist Modernity II: Dissecting Capitalist Modernity–Building Democratic Confederalism”, 3–5 April 2015, Hamburg. Texts of the conference are published at http://networkaq.net/2015/speeches 2.5 Federico Venturini Social Ecology and the non-Western World Murray Bookchin was the founder of the social ecology, a philosophical perspective whose political project is called libertarian municipalism or Communalism. Recently there has been a revival of interest in this project, due to its influence on the socio-political organization in Rojava, a Kurdish self-managed region in the Syrian state. This should not be a surprise because Bookchin's works influenced Abdul Öcalan for a more than a decade, a key Kurdish leader who developed a political project called Democratic Confederalism. We should all welcome this renewed interest in social ecology and take lessons from the Rojava experience. Bookchin's analyses have always been more focussed on North-American or European experiences and so libertarian municipalism draws from these traditions. Moreover, Bookchin, who was writing in a Cold war scenario, was suspicious of the limits of national movements struggling for independence. The aim of this paper is to develop and enlarge Bookchin's analysis, including experiences and traditions from different cultures and movements, and their interrelations on a global scale. First, it explores social ecology perspective in non- Western contexts. Second, it will introduce new tools to deal with inter-national relations based on world system theory. Third, it will suggests that new experiences coming from non-Western regions can strength social ecology understanding and practices. -

Bookchin's Libertarian Municipalism

BOOKCHIN’S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM Janet BIEHL1 ABSTRACT: The purpose of this article is to present the Libertarian Municipalism Theory developed by Murray Bookchin. The text is divided into two sections. The first section presents the main precepts of Libertarian Municipalism. The second section shows how Bookchin’s ideas reached Rojava in Syria and is influencing the political organization of the region by the Kurds. The article used the descriptive methodology and was based on the works of Murray Bookchin and field research conducted by the author over the years. KEYWORDS: Murray Bookchin. Libertarian Municipalism. Rojava. Introduction The lifelong project of the American social theorist Murray Bookchin (1921-2006) was to try to perpetuate the centuries-old revolutionary socialist tradition. Born to socialist revolutionary parents in the Bronx, New York, he joined the international Communist movement as a Young Pioneer in 1930 and trained to become a young commissar for the coming proletarian revolution. Impatient with traditional secondary education, he received a thoroughgoing education in Marxism-Leninism at the Workers School in lower Manhattan, immersing himself in dialectical materialism and the labor theory of value. But by the time Stalin’s Soviet Union formed a pact with Nazi Germany (in the sum- mer of 1939), he cut his ties with the party to join the Trotskyists, who expected World War II to end in international proletarian revolutions. When the war 1 Janet Biehl is an American political writer who is the author of numerous books and articles associated with social ecology, the body of ideas developed and publicized by Murray Bookchin. -

Nationbuilding in Rojava

СТАТЬИ, ИССЛЕДОВАНИЯ, РАЗРАБОТКИ Кризисы и конфликты на Ближнем и Среднем Востоке M.J.Moberg NATION-BUILDING IN ROJAVA: PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY AMIDST THE SYRIAN CIVL WAR Название Национальное строительство в Роджаве: демократия участия в условиях на рус. яз. гражданской войны в Сирии Ключевые Сирия, гражданская война, сирийские курды, Роджава, демократический конфе- слова: дерализм Аннотация: В условиях гражданской войны в Сирии местные курды успешно использовали ослабление центральной власти для того, чтобы построить собственную систему самоуправления, известную как Роджава. Несмотря на то, что курдские силы на севере Сирии с энтузиазмом продвигают антинационалистическую программу левого толка, они сами при этом находятся в процессе национального строительства. Их главный идеологический принцип демократического конфедерализма объединяет элементы гражданского национализма и революционного социализма с целью создания новой нации в Сирии, построенной на эгалитарных началах. Политическая система Роджавы основана на принципах демократии участия (партиципаторной демократии) и федерализма, позволяющих неоднородному населению ее кантонов участвовать в самоуправлении на уровнях от локального до квазигосударственного. Хотя вопрос о признании Роджавы в ходе мирного процесса под эгидой ООН и политического урегулирования в Сирии остается открытым, практикуемый ей демократический конфедерализм может уже служить моделью инклюзивной партиципаторной демократии. Keywords: Syria, civil war, Syrian Kurds, Rojava, democratic confederalism Abstract: During -

Social Ecology and Democratic Confederalism-Eng

1 www.makerojavagreenagain.org facebook.com/GreenRojava twitter.com/GreenRojava [email protected] July 2020 Table of Contents 1 Abdullah Öcalan on the return to social ecology 6 Abdullah Öcalan 2 What is social ecology? 9 Murray Bookchin 3 The death of Nature 28 Carolyn Merchant 4 Ecology in Democratic Confederalism 33 Ercan Ayboga 5 Reber Apo is a Permaculturalist - Permaculture and 55 Political Transformation in North East Syria Viyan Qerecox 6 Ecological Catastrophe: Nature Talks Back 59 Pelşîn Tolhildan 7 Against Green Capitalism 67 Hêlîn Asî 8 The New Paradigm: Weaving ecology, democracy and gender liberation into a revolutionary political 70 paradigm Viyan Querecox 1 Abdullah Öcalan on the return to social ecology By Abdullah Öcalan Humans gain in value when they understand that animals and plants are only entrusted to them. A social 'consciousness' that lacks ecological consciousness will inevitably corrupt and disintegrate. Just as the system has led the social crisis into chaos, so has the environment begun to send out S.O.S. signals in the form of life-threatening catastrophes. Cancer-like cities, polluted air, the perforated ozone layer, the rapidly accelerating extinction of animal and plant species, the destruction of forests, the pollution of water by waste, piling up mountains of rubbish and unnatural population growth have driven the environment into chaos and insurrection. It's all about maximum profit, regardless of how many cities, people, factories, transportation, synthetic materials, polluted air and water our planet can handle. This negative development is not fate. It is the result of an unbalanced use of science and technology in the hands of power. -

Year 8 Winning Essays for Website

The Very Important Virtue of Tolerance Christian Torsell University of Notre Dame Introduction The central task of moral philosophy is to find out what it is, at the deepest level of reality, that makes right acts right and good things good. Or, at least, someone might understandably think that after surveying what some of the discipline’s most famous practitioners have had to say about it. As it is often taught, ethics proceeds in the shadows of three towering figures: Aristotle, Kant, and Mill. According to this story, the Big Three theories developed by these Big Three men— virtue ethics, deontology, and utilitarianism—divide the terrain of moral philosophy into three big regions. Though each of these regions is very different from the others in important ways, we might say that, because of a common goal they share, they all belong to the same country. Each of these theories aims to provide an ultimate criterion by which we can Judge the rightness or wrongness of acts or the goodness or badness of agents. Although the distinct criteria they offer pick out very different features of acts (and agents) as relevant in making true Judgments concerning rightness and moral value, they each claim to have identified a standard under which all such judgments are properly united. Adam Smith’s project in The Theory of Moral Sentiments1 (TMS) belongs to a different country entirely. Smith’s moral theory does not aim to give an account of the metaphysical grounding of moral properties—that is, to describe the features in virtue of which right actions and 1 All in-text citations without a listed author refer to this work, Smith (2004). -

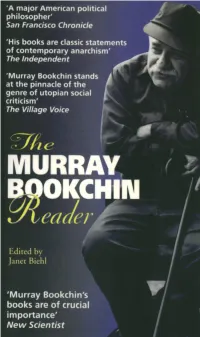

The Murray Bookchin Reader

The Murray Bookchin Reader We must always be on a quest for the new, for the potentialities that ripen with the development of the world and the new visions that unfold with them. An outlook that ceases to look for what is new and potential in the name of "realism" has already lost contact with the present, for the present is always conditioned by the future. True development is cumulative, not sequential; it is growth, not succession. The new always embodies the present and past, but it does so in new ways and more adequately as the parts of a greater whole. Murray Bookchin, "On Spontaneity and Organization," 1971 The Murray Bookchin Reader Edited by Janet Biehl BLACK ROSE BOOKS Montreal/New York London Copyright © 1999 BLACK ROSE BOOKS No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system-without written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from the Canadian Reprography Collective, with the exception of brief passages quoted by a reviewer in a newspaper or magazine. Black Rose Books No. BB268 Hardcover ISBN: 1-55164-119-4 (bound) Paperback ISBN: 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-71026 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Bookchin, Murray, 1921- Murray Bookchin reader Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55164-119-4 (bound). ISBN 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) 1. Libertarianism. 2. Environmentalism. 3. Human ecology. -

Anarchist Social Democracy

Anarchist Social Democracy * By W. J. Whitman Anarchist social democracy would be a form of cellular democracy or democratic confederalism, where governance is done locally through grassroots democratic assemblies. This libertarian social democracy would differ from the models of Bookchin and Öcalan in that it would be a form of market anarchism rather than communism. It would be mutualist, distributist, and collectivist, but not communist (although communistic arrangements would be common within it). The democratic confederation would follow the distributist principle of “subsidiarity,” trying to ensure that all matters are handled by the smallest and most local level of government capable of effectively carrying out the task. The majority of decisions that directly affect people would be made locally, in popular assemblies through direct democracy. The assemblies would use a mixture of consensus processes and voting, depending on how important the decision is. Non- essential and non-controversial matters might be put to a * The flag of Anarchist Social Democracy is a red and black banner for anarchism (libertarian socialism) with a globe (earth) in the middle for Georgism and social ecology. The dog is the “hound of distributism” carrying the red rose that is symbolic of social democracy. 1 | No rights reserved; for there is no such thing as intellectual property. popular vote, while important decisions would require consensus. Delegates from the local democratic assemblies would be sent to district councils, delegates from the district councils would be sent to municipal councils, and so on to regional councils, provincial councils, and all the way to national and even international councils. -

A Social-Ecological Perspective on Degrowth As a Political Ideology

Capitalism Nature Socialism ISSN: 1045-5752 (Print) 1548-3290 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcns20 Beyond the Limits of Nature: A Social-ecological Perspective on Degrowth as a Political Ideology Eleanor Finley To cite this article: Eleanor Finley (2018): Beyond the Limits of Nature: A Social-ecological Perspective on Degrowth as a Political Ideology, Capitalism Nature Socialism, DOI: 10.1080/10455752.2018.1499122 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2018.1499122 Published online: 23 Jul 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 36 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcns20 CAPITALISM NATURE SOCIALISM https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2018.1499122 Beyond the Limits of Nature: A Social-ecological Perspective on Degrowth as a Political Ideology Eleanor Finley Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA ABSTRACT This article offers a critical analysis of the ideological position of degrowth from the perspective of social ecology. It agrees with Giorgios Kallis’ call to abolish the growth imperative that capitalism embodies today, but it also presents a critique of the conceptual underpinnings of this notion. More precisely, I argue that degrowth as an ideological platform reproduces a binary conception of society and nature, an oppositional mentality which is a key concept to hierarchical epistemology. Degrowth as a political agenda is thus prone to appropriation to authoritarian ends. In order to temper this tendency and help degrowth as a tool of analysis reach its liberatory potential, I advocate its consideration alongside a social-ecological position. -

Political Parties and the Market

POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE MARKET - Towards a Comparable Assessment of Market Liberalism Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln 2018 Dipl. Pol. Leonce Röth aus Hennef/Sieg - 0 - Referent: Prof. Dr. André Kaiser Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Ingo Rohlfing Tag der Promotion: 13.07.2018 - 1 - Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... v Collaboration with co-authors ........................................................................................................ ix Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1 PART I | THE CONCEPT OF MARKET LIBERALISM ................................................... 15 1. The conceptual foundation........................................................................................... 15 1.1 The core elements of market liberalism ...................................................................... 19 1.2 Adjacent elements of market liberalism ...................................................................... 21 1.3 Party families and market liberalism ............................................................................ 24 1.4 Intervention without states ........................................................................................... 32 1.5 The peripheral elements ...............................................................................................