This Is an Electronic Reprint of the Original Article. This Reprint May Differ from the Original in Pagination and Typographic Detail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finnland Hamburg · 14.10.2009

aktuell OFFIZIELLES PROGRAMM DES DEUTSCHEN FUSSBALL-BUNDES · 6/2009 · SCHUTZGEBÜHR 1,– ¤ WM-Qualifikationsspiel Deutschland – Finnland Hamburg · 14.10.2009 Mit Super-Gewinnspiel und Riesen-Poster! www.dfb.de · www.fussball.de 200 Hektar Anbaufläche Jahre Erfahrung Dr. Georg Stettner 20 Qualitätsprüfer 1 Blick fürs Detail Unser Anspruch ist es nur die beste Braugerste zu verarbeiten. Daher verwenden wir nur ausgewählte Gerstensorten. Diese Sorgfalt für unser Gerstenmalz schmecken Sie mit jedem Schluck. Alles für diesen Moment: Liebe Zuschauer, unsere Nationalmannschaft hat sich in Moskau wieder ein- mal von ihrer besten Seite gezeigt und die Lobeshymnen auf ihre starke Leistung, die überall zu lesen und zu hören sind, sind vollauf berechtigt. Bereits kurz nach dem Spiel beim gemeinsamen Essen im Hotel habe ich mich bei ihr und den Trainern für einen unvergesslichen Fußball-Abend bedankt. Unser Team hat sich bei dem Sieg gegen Russland so präsentiert, wie sich das Millionen Fans wünschen. Die DFB-Auswahl hat gleichzeitig eindrucksvoll bewiesen, dass sie das Flaggschiff des deutschen Fußballs ist. Damit hat sie sich vor der letzten, heute auf dem Terminplan stehenden WM-Qualifikations-Begegnung mit Finnland direkt für das Stelldichein der 32 weltbesten National mann - schaften im kommenden Sommer in Südafrika qualifiziert. Zum 15. Mal in Folge seit 1954 ist damit unser Team bei der WM-Endrunde dabei. Natürlich erfüllt uns das alle mit Stolz, zumal die DFB-Auswahl zum wiederholten Mal in Moskau bewiesen hat, dass in wichtigen Duellen einfach Verlass auf sie ist, sie sich im entscheidenden Moment nicht nur kämpferisch, sondern genauso spielerisch immer steigern kann und zu Recht in der FIFA-Weltrangliste zu den Topteams gehört. -

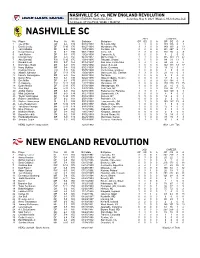

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Jalkapallon Periferia Ja Arvokisattomuuden Traumat

JALKAPALLON PERIFERIA JA ARVOKISATTOMUUDEN TRAUMAT Helsingin Sanomien ja Urheilulehden suhtautuminen Suomen miesten jalkapallomaajoukkueeseen arvoturnauskarsinnoissa 1996–1997 ja 2006–2007 Oulun yliopisto Historiatieteet Pro gradu -tutkielma 18.5.2015 Juho Kanto Sisällys JOHDANTO ..................................................................................................................... 3 Arvoturnausunelmaa metsästämässä .................................................................... 3 Tutkimustilanne ...................................................................................................... 6 Tutkimustehtävä ..................................................................................................... 8 Lähteet .................................................................................................................... 10 Menetelmät ............................................................................................................ 13 1. MAAJOUKKUEELLE TAHDIT TANSKASTA – RICHARD MÖLLER NIELSENIN AIKA ......................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Mahdoton tehtävä vaatii ammattimiehen .................................................... 16 1.2. Ammattilaisuus ihanteena – Onko maajoukkue mitään ilman Littiä? ..... 29 1.3. Yleisöä ja kansainvälistä menestystä vailla ................................................. 37 2. VERKKAREISTA LIITURAITAPUKUUN – ROY HODGSONIN AIKA.............. 44 2.1. Sir Roy – Brittiläinen realisti -

Die Bundesliga Ist Zum Greifen Nah Florian Müller Aus Lebach Spielt Beim FSV Mainz 05

Donnerstag, 2. Februar 2017 D1 FUSSBALL HANDBALL Der DFB sucht zehn Stadien für die Euro- Der Kapitän geht von Bord: Zweitligist pameisterschaft 2024. Auch Kaiserslau- HG Saarlouis verliert am Saisonende tern möchte sich bewerben. Seite D 2 Sport Spielführer Jonas Faulenbach. Seite D 3 WWW.SAARBRUECKER-ZEITUNG.DE/SPORT SERIE SAARLÄNDER IM PROFI-FUSSBALL, TEIL 1 Die Bundesliga ist zum Greifen nah Florian Müller aus Lebach spielt beim FSV Mainz 05. Trainer Martin Schmidt bescheinigt dem 19-Jährigen ein „Riesenpotenzial“. VON TOBIAS FUCHS MAINZ Es gibt die zwei Zeiten des Florian Müller. In der einen hat ein Jahr meist 365 Tage. Die andere Zeit ist schwer berechenbar. Noch im Dezember sagte Martin Schmidt, sein Trainer beim Fuß- ball-Bundesligisten FSV Mainz 05, er traue Müller „in den nächsten zwei, drei Jahren“ die erste Liga zu. Im Januar bescheinigte Schmidt dem Nachwuchstorwart ein „Rie- senpotenzial und die Perspektive, in den nächsten eineinhalb, zwei Jahren zum Bundesliga-Spieler zu reifen“. Eineinhalb statt zwei Jah- re: Innerhalb weniger Tage war in der Zeitrechnung von Müllers Karriere offenbar ein halbes Jahr vergangen. Mit 19 Jahren hütet der Leba- cher längst das Tor der U 23 von Mainz 05 in der 3. Liga. Auch in der deutschen U 20-Nationalmann- schaft war er zuletzt gesetzt. Am 22. März trifft die Auswahl in El- versberg auf die Schweiz. Beim FV Lebach fing für Müller alles an, „mit drei oder vier Jah- ren“. Einer seiner Trainer: Chris- toph Mees. Für den 1. FC Saarbrü- Torwart Florian Müller wechselte als Jugendlicher zum Fußball-Bundesligisten FSV Mainz 05. Heute spielt der Saarländer mit der U 23 in der 3. -

2021 Topps MLS Checklist(1).Xls

BASE CARDS 1 Ryan Hollingshead FC Dallas 2 Mustafa Kizza CLUB DE FOOT MONTRÉAL Rookie 3 Bradley Wright-Phillips LAFC 4 Yimmi Chara Portland Timbers 5 Memo Rodriguez Houston Dynamo 6 Jonathan dos Santos LA Galaxy 7 Jozy Altidore Toronto FC 8 Dante Sealy FC Dallas 9 Jamiro Monteiro Philadelphia Union 10 Ezequiel Barco Atlanta United FC 11 Achara Toronto FC 12 Sebastian Blanco Portland Timbers 13 Julian Gressel D.C. United 14 Bill Hamid D.C. United 15 Alejandro Bedoya Philadelphia Union 16 Michael Barrios Colorado Rapids 17 Mauricio Pineda Chicago Fire FC 18 Thomas Roberts FC Dallas 19 Robert Beric Chicago Fire FC 20 Mauricio Pereyra Orlando City SC 21 Carlos Vela LAFC 22 Jonathan Osorio Toronto FC 23 Blaise Matuidi Inter Miami CF 24 Kevin Molino Columbus Crew SC 25 Cristian Roldan Seattle Sounders FC 26 Romain Metanire Minnesota United 27 Dave Romney Nashville SC 28 Stefan Frei Seattle Sounders FC 29 Fabian Herbers Chicago Fire FC 30 Eddie Segura LAFC 31 Kacper Przybylko Philadelphia Union 32 Justin Meram Real Salt Lake 33 Paxton Pomykal FC Dallas 34 Lewis Morgan Inter Miami CF 35 Daniel Royer New York Red Bulls 36 Diego Rubio Colorado Rapids 37 Omar Gonzalez Toronto FC 38 Diego Rossi LAFC 39 Haris Medunjanin FC Cincinnati 40 Marko Maric Houston Dynamo 41 Jan Gregus Minnesota United 42 Alvaro Medran Chicago Fire FC 43 Johnny Russell Sporting Kansas City 44 Miles Robinson Atlanta United FC 45 Kyle Duncan New York Red Bulls 46 Heber New York City FC 47 Valentin Castellanos New York City FC 48 Aaron Long New York Red Bulls 49 Chris Wondolowski -

Suomen Palloliitto VUOSIKERTOMUS 2016 SISÄLTÖ JOHDANTO

Suomen Palloliitto VUOSIKERTOMUS 2016 SISÄLTÖ JOHDANTO ......................................................................................................................... 5 PÄÄVALINNAT PELAAJAN LAADUKAS ARKI ....................................................................................... 7 ELINVOIMAINEN SEURA ............................................................................................... 15 MIELENKIINTOISET KILPAILUT .................................................................................. 21 JALKAPALLOPERHEEN AKTIIVINEN VIESTINTÄ JA VAIKUTTAMINEN...... 25 KEHITYSOHJELMAT ........................................................................................................ 29 - SEUROJEN PALLOLIITTO - PÄÄSARJOJEN JA PÄÄSARJASEUROJEN KASVUPAKETTI HALLINTO JA TUKITOIMINNOT ................................................................................. 31 TILASTOT ............................................................................................................................. 35 ÅRSBERÄTTELSE ............................................................................................................... 53 Suomen Palloliitto 3 JOHDANTO Suomalaisen jalkapallon ja futsalin uuden toimintastrategian rakentaminen aloitettiin jo vuoden 2015 puolel- la ja strategiaa viimeisteltiin alkuvuodesta 2016. Strategia vuosille 2016-20 hyväksyttiin Suomen Palloliiton 88. varsinaisessa liittokokouksessa Tampereella 23. – 24.4.2016. Strategiaprosessin aikana kuunneltiin laajasti eri toimijoiden käsityksiä -

The Thrill and the Truth ❏ Aretha Franklin Dies at 76 After Unchallenged Reign As Greatest Vocalist of Her Time

FRIDAY,AUG. 17, 2018 Inside: 75¢ GOP divided over Space Force. — Page 6A Vol. 90 ◆ No. 119 SERVING CLOVIS, PORTALES AND THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES EasternNewMexicoNews.com Los Angeles Times: Lawrence K. Ho Aretha Franklin in concert at the Microsoft Theatre in Los Angeles on Aug. 2, 2015. The thrill and the truth ❏ Aretha Franklin dies at 76 after unchallenged reign as greatest vocalist of her time. Detroit Free warning to “Think.” By Hillel Italie Press: THE ASSOCIATED PRESS Richard Lee Acknowledging the obvious, Rolling Stone ranked her first on NEW YORK — The clarity and James its list of the top 100 singers. the command. The daring and the Brown, Franklin was also named one of discipline. The thrill of her voice right, per- the 20 most important entertainers and the truth of her emotions. forms with of the 20th century by Time mag- Like the best actors and poets, Aretha azine, which celebrated her nothing came between how Franklin in “mezzo-soprano, the gospel Aretha Franklin felt and what she Detroit, growls, the throaty howls, the girl- ish vocal tickles, the swoops, the could express, between what she Michigan, in expressed and how we responded. dives, the blue-sky high notes, the January Blissful on “(You Make Me Feel blue-sea low notes. Female vocal- Like) a Natural Woman.” 1987. ists don’t get the credit as innova- Despairing on “Ain’t No Way.” tors that male instrumentalists do. Up front forever on her feminist As surely as Jimi Hendrix settled mid-20s, she recorded hundreds They should. Franklin has mas- and civil rights anthem “Respect.” arguments over who was the No. -

UEFA EURO - SAISON 2019/21 PRESSEMAPPEN Saint Petersburg Stadium - St

UEFA EURO - SAISON 2019/21 PRESSEMAPPEN Saint Petersburg Stadium - St. Petersburg Montag, 21. Juni 2021 Finnland 21.00MEZ (22.00 Ortszeit) Belgien Gruppe B - Spieltag 3 Letzte Aktualisierung 13/07/2021 11:49MEZ Offizielle Partner der UEFA EURO 2020 Frühere Begegnungen 2 Ausgangslage 3 Kader 5 Spielverantwortliche 7 Fakten zu den Mannschaften 8 Aufstellungen im Wettbewerb 11 Wettbewerbsfakten 14 Legende 19 1 Finland - Belgium Montag 21 Juni 2021 - 21.00CET (22.00 Ortszeit) Pressemappe Saint Petersburg Stadium, St. Petersburg Frühere Begegnungen Direkte Duelle UEFA EURO 2008 Erreichte Datum Spiel Ergebnis Spielort Torschützen Runde 13/10/2007 QR (GP) Belgien - Finnland 0-0 Brüssel Johansson 27, A. 06/06/2007 QR (GP) Finnland - Belgien 2-0 Helsinki Eremenko 71 FIFA-Weltpokal Erreichte Datum Spiel Ergebnis Spielort Torschützen Runde Puis 18 (E), 77, Polleunis 30, 39, 63, 09/10/1968 QR (GP) Belgien - Finnland 6-1 Waregem Semmeling 49; Lindholm 88 (E) Flink 16; Devrindt 85, 19/06/1968 QR (GP) Finnland - Belgien 1-2 Helsinki Polleunis 89 FIFA-Weltpokal Erreichte Datum Spiel Ergebnis Spielort Torschützen Runde Bollen 23, 80; 23/09/1953 QR (GP) Belgien - Finnland 2-2 Brussels Lahtinen 83, Vaihela 90 Lehtovirta 51, 75; 25/05/1953 QR (GP) Finnland - Belgien 2-4 Helsinki Coppens 8, 25, 80, Anoul 10 Qualifikation Endrunde Gesamt Heim Auswärtsmannschaft Sp. S U N Sp. S U N Sp. S U N Sp. S U N ET KT EURO Finnland 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 - - - - 2 1 1 0 2 0 Belgien 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 - - - - 2 0 1 1 0 2 FIFA* Finnland 2 0 0 2 2 0 1 1 - - - - 4 0 1 3 6 14 Belgien 2 1 1 0 2 2 0 0 - - - - 4 3 1 0 14 6 Freundschaftsspiele Finnland - - - - - - - - - - - - 5 3 2 0 11 6 Belgien - - - - - - - - - - - - 5 0 2 3 6 11 Gesamt Finnland 3 1 0 2 3 0 2 1 - - - - 11 4 4 3 19 20 Belgien 3 1 2 0 3 2 0 1 - - - - 11 3 4 4 20 19 * FIFA-Weltpokal/FIFA Konföderationen-Pokal 2 Finland - Belgium Montag 21 Juni 2021 - 21.00CET (22.00 Ortszeit) Pressemappe Saint Petersburg Stadium, St. -

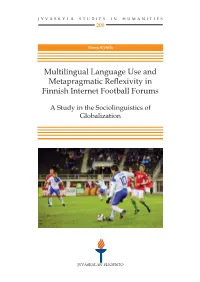

Multilingual Language Use and Metapragmatic Reflexivity in Finnish Internet Football Forums. a Study in the Sociolinguistics of Globalization

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 200 Samu Kytölä Multilingual Language Use and Q< JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 200 Samu Kytölä Multilingual Language Use and Metapragmatic Reflexivity in Finnish Internet Football Forums A Study in the Sociolinguistics of Globalization Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston vanhassa juhlasalissa S212 maaliskuun 21. päivänä 2013 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in Auditorium S212, on March 21, 2013 at 12 o’clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2013 Multilingual Language Use and Metapragmatic Reflexivity in Finnish Internet Football Forums A Study in the Sociolinguistics of Globalization JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 200 Samu Kytölä Multilingual Language Use and Metapragmatic Reflexivity in Finnish Internet Football Forums A Study in the Sociolinguistics of Globalization UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2013 Editors Paula Kalaja Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Pekka Olsbo, Ville Korkiakangas Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Paula Kalaja, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Tarja Nikula, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä Cover picture by Tero Wester. URN:ISBN:978-951-39-5132-0 ISBN 978-951-39-5132-0 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-5131-3 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4323 (nid.), 1459-4331 (PDF) Copyright © 2013, by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2013 Human beings use linguistic features, words with meanings, morphology, syntactic restrictions and, as we have seen, values ascribed to them by speakers. -

Raja-Aho Juuso.Pdf (438.7Kt)

Juuso Raja-Aho VAPAUTETTU TEHTÄVÄSTÄ – POTKUT TULI? Urheiluseurojen tiedotteiden ja Ilta-Sanomien uutisten väliset erot valmentajan vaihdon käsittelyssä VAPAUTETTU TEHTÄVÄSTÄ – POTKUT TULI? Urheiluseurojen tiedotteiden ja Ilta-Sanomien uutisten väliset erot valmentajan vaihdon käsittelyssä Juuso Raja-Aho Opinnäytetyö Syksy 2020 Viestinnän tutkinto-ohjelma Oulun ammattikorkeakoulu TIIVISTELMÄ Oulun ammattikorkeakoulu Viestinnän tutkinto-ohjelma, Journalismi Tekijä: Juuso Raja-Aho Opinnäytetyön nimi: Vapautettu tehtävästä – potkut tuli? Urheiluseurojen tiedotteiden ja Ilta-Sanomien uutisten väliset erot valmentajan vaihdon käsittelyssä Työn ohjaajat: Satu Koho & Teemu Palokangas Työn valmistumislukukausi ja -vuosi: Syksy 2020 Sivumäärä: 45 + 1 liite Tässä opinnäytetyössä tarkastelen, miten suomalaiset jalkapallo- ja jääkiekkoseurat tiedottavat kesken kauden tapahtuvasta päävalmentajan vaihtamisesta, ja miten Ilta-Sanomat uutisoi sa- moista tapauksista. Kehysanalyysin avulla selvitän esimerkiksi, millä tavalla seurojen ja Ilta-Sanomien tavat kertoa uu- den päävalmentajan historiasta eroavat toisistaan. Millaisia asioita valmentajan historiasta noste- taan esiin ja mitä jätetään vähemmälle huomiolle? Retorista analyysia käytän selvittäessäni, millä tavoilla seurat yrittävät vakuuttaa tehneensä oikean päätöksen. Analysoin myös seurojen ja toimittajien käyttämiä kielikuvia, kuten metaforia. Millaiset perustelut ja metaforat toistuvat teksteissä? Näiden rinnalla käytän sisällönanalyysia, kun käyn läpi seurojen tiedotteita ja Ilta-Sanomien uutisia -

Suomen Palloliiton Vuosikertomus 2013

SUOMEN PALLOLIITTO VUOSIKERTOMUS 2013 VOITTOJA JOKA PÄIVÄ Sisältö Huippujalkapallo .................................................................. 4 Seurakehitys .......................................................................... 13 Hallinto .................................................................................... 19 Liittohallitus .......................................................................... 22 Liittovaltuusto ...................................................................... 23 Mestarit ja menestyjät ........................................................ 24 Vuoden parhaat .................................................................... 26 Maaottelut .............................................................................. 28 Rekisteröidyt pelaajat ....................................................... 31 Yhteiset mittarit -tilasto toimintavuodelta 2013 ........ 32 Piirien seurat ja joukkueet ............................................... 34 Infosivut .................................................................................. 35 Toppfotboll .............................................................................. 44 Föreningsutveckling ........................................................... 50 Administration...................................................................... 55 Valokuvat: Jussi Eskola ja Ville Vuorinen 2 SUOMEN PALLOLIITTO – VUOSIKERTOMUS 2013 Alexander Ring ja Teemu Pukki tuulettavat 1–1-osumaa Gijónissa maaliskuussa Hannu Tihinen nimitettiin Palloliiton -

Supertähden Ilmaantuminen on Oletettavasti Vain Ajan Kysymys” Maahanmuuttajat Ja Suomalaisen Jalkapalloilun Tulevaisuus

”Supertähden ilmaantuminen on oletettavasti vain ajan kysymys” Maahanmuuttajat ja suomalaisen jalkapalloilun tulevaisuus Marko Kananen Maahanmuuttotaustaiset jalkapalloilijat ovat nousseet 2000-luvulla nopeasti suomalaisen jalkapalloilun huipulle. Tässä artikkelissa tarkastellaan sitä, kuinka maahanmuuttotaustaisia pelaajia on käsitelty suomalaisessa mediassa. Millaisia niin positiivisia kuin negatiivisia ominaisuuksia ja ennakko-oletuksia heihin on liitetty ja millaisia rooleja heille on tarjottu? Analyysin tulokset tuovat esiin maahanmuuttotaustaisia pelaajia koskevassa kirjoittelussa korostuvaa tasapainoilua poikkeuksellisia jalkapallotaitoja korostavan meritokratiapuheen ja asenneongelmia käsittelevän huolipuheen välillä. Näiden perinteisten käsittelytapojen lisäksi mediassa on kuitenkin myös nähtävissä merkkejä maahanmuuttotaustaisten pelaajien normalisoitumisesta osaksi suomalaisen jalkapalloilun arkea. Suomen miesten jalkapallomaajoukku- netta lukuun ottamatta arvokisapaikka mukaan jalan sijaa periferiatrauma, jos- een historiikissa toimittaja Antti Eerola näyttikin pitkään jäävän pelkäksi unel- sa menestyvää ja uskottavaa jalkapalloa (2015) kuvaa Suomea ”jalkapallomaa- maksi vuodesta 1938 karsintoja pelan- pelattiin aina jossain muualla, kun taas ilman Aku Ankaksi”, joka sinnikkäästä neelle miesten maajoukkueelle. Tämän Suomessa oltiin vain ”pohjoisia pallon- yrityksestä huolimatta möhlii mahdolli- vuosikymmeniä kestäneen korpivael- potkijoita”. suutensa arvokisoihin aina ratkaisevalla luksen myötä suomalaisen jalkapalloi- Vuosituhannen