Partisan Balance with Bite Brian D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kentucky Lawyer, 1993

KENTUCKY UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY COLLEGE OF LAW-1993 APANTHEON OF DEANS: Tom Lewis, Bob Lawson, David Shipley and Bill' Campbell Ci David Shipley becomes Dean of the College of Law he College of Law welcomes David E. fall. His areas of legal expertise are copyright and ad Shipley as its new dean, effective July 1, ministrative law. His most recent publication is a 1993. Dean Shipley comes to us from the casebook, Copyright Law: Cases and Materials, West ~---~ University of Mississippi School of Law, Publishing 1992, with co-authors Howard Abrams of the where he served as Dean and Director of the Law Center University of Detroit School of Law and Sheldon for the last three years. Halpern of Ohio State University. Shipley also has Dean Shipley was raised in Champaign, Illinois, and published two editions of a treatise on administrative was graduated from University High School at the Uni procedure in South Carolina entitled South Carolina versity of Illinois. He received his B.A. degree with Administrative Law. He has taught Civil Procedure, Highest Honors in American History from Oberlin Col- Remedies, Domestic Relations and Intellectual Property lege in 1972, and is as well as Copyright and Administrative Law. In addi a 1975 graduate of tion, he has participated in a wide variety of activities the University of and functions sponsored by the South Carolina and Mis Chicago Law sissippi bars. School, where he Dean Shipley enjoys reading best-selling novels by was Executive authors such as Grisham, Crichton, Turow and Clancy as Editor of the Uni well as history books about the Civil War. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 155 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, JANUARY 12, 2009 No. 6 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Tuesday, January 13, 2009, at 12:30 p.m. Senate MONDAY, JANUARY 12, 2009 The Senate met at 2 p.m. and was The legislative clerk read the fol- was represented in the Senate of the called to order by the Honorable JIM lowing letter: United States by a terrific man and a WEBB, a Senator from the Common- U.S. SENATE, great legislator, Wendell Ford. wealth of Virginia. PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, Senator Ford was known by all as a Washington, DC, January 12, 2009. moderate, deeply respected by both PRAYER To the Senate: sides of the aisle for putting progress The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, ahead of politics. Senator Ford, some of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby fered the following prayer: appoint the Honorable JIM WEBB, a Senator said, was not flashy. He did not seek Let us pray. from the Commonwealth of Virginia, to per- the limelight. He was quietly effective Almighty God, from whom, through form the duties of the Chair. and calmly deliberative. whom, and to whom all things exist, ROBERT C. BYRD, In 1991, Senator Ford was elected by shower Your blessings upon our Sen- President pro tempore. his colleagues to serve as Democratic ators. -

Reform and Reaction: Education Policy in Kentucky

Reform and Reaction Education Policy in Kentucky By Timothy Collins Copyright © 2017 By Timothy Collins Permission to download this e-book is granted for educational and nonprofit use only. Quotations shall be made with appropriate citation that includes credit to the author and the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University. Published by the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University in cooperation with Then and Now Media, Bushnell, IL ISBN – 978-0-9977873-0-6 Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs Stipes Hall 518 Western Illinois University 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455-1390 www.iira.org Then and Now Media 976 Washington Blvd. Bushnell IL, 61422 www.thenandnowmedia.com Cover Photos “Colored School” at Anthoston, Henderson County, Kentucky, 1916. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ item/ncl2004004792/PP/ Beechwood School, Kenton County Kentucky, 1896. http://www.rootsweb.ancestry. com/~kykenton/beechwood.school.html Washington Junior High School at Paducah, McCracken County, Kentucky, 1950s. http://www. topix.com/album/detail/paducah-ky/V627EME3GKF94BGN Table of Contents Preface vii Acknowledgements ix 1 Reform and Reaction: Fragmentation and Tarnished 1 Idylls 2 Reform Thwarted: The Trap of Tradition 13 3 Advent for Reform: Moving Toward a Minimum 30 Foundation 4 Reluctant Reform: A.B. ‘Happy” Chandler, 1955-1959 46 5 Dollars for Reform: Bert T. Combs, 1959-1963 55 6 Reform and Reluctant Liberalism: Edward T. Breathitt, 72 1963-1967 7 Reform and Nunn’s Nickle: Louie B. Nunn, 1967-1971 101 8 Child-focused Reform: Wendell H. Ford, 1971-1974 120 9 Reform and Falling Flat: Julian Carroll, 1974-1979 141 10 Silent Reformer: John Y. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950. -

Chapter Eight Reference Documentation

Chicago O’Hare International Airport Final EIS CHAPTER EIGHT REFERENCE DOCUMENTATION This Chapter consists of the following sections: • 8.1 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms • 8.2 Glossary • 8.3 Environmental Laws and Regulations • 8.4 Reference Documents • 8.5 List of Preparers • 8.6 List of Recipients • 8.7 Index 8.1 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AACGR Average Annual Compound AGL Above Ground Level OR FAA, Growth Rate Great Lakes Region AADT Annual Average Daily Traffic AGI Airport Group International AAIA Airport and Airway AHERA Asbestos Hazard Emergency Improvement Act Response Act AC Advisory Circular OR Asphalt AIA American Institute of Architects Concrete AIP Airport Improvement Program ACF Advanced Chemical AIR-21 Wendell Ford Aviation Fingerprinting Investment & Reform Act for ACHP Advisory Council on Historic the 21st Century Preservation AISC American Institute of Steel ACI Airports Council International Construction, Inc. ADA The Airline Deregulation Act of ALP Airport Layout Plan 1978 ALPA Air Line Pilots Association ADC Animal Damage Control ALS Approach Light System ADG Airport Design Group VI ALSF-2 High Intensity Approach ADO FAA Airports District Office Lighting System with Sequenced Flashers AEM Area Equivalent Method AMC Airport Maintenance Complex AF Airway Facilities Division, FAA AN Ammonia Nitrogen AFTPro Advanced Flight Track Procedures ANCA Airport Noise and Capacity Act Reference Documentation 8-1 July 2005 Chicago O’Hare International Airport Final EIS ANMS Airport Noise Monitoring ATS Airport Transit -

Student Research- Women in Political Life in KY in 2019, We Provided Selected Museum Student Workers a List of Twenty Women

Student Research- Women in Political Life in KY In 2019, we provided selected Museum student workers a list of twenty women and asked them to do initial research, and to identify items in the Rather-Westerman Collection related to women in Kentucky political life. Page Mary Barr Clay 2 Laura Clay 4 Lida (Calvert) Obenchain 7 Mary Elliott Flanery 9 Madeline McDowell Breckinridge 11 Pearl Carter Pace 13 Thelma Stovall 15 Amelia Moore Tucker 18 Georgia Davis Powers 20 Frances Jones Mills 22 Martha Layne Collins 24 Patsy Sloan 27 Crit Luallen 30 Anne Northup 33 Sandy Jones 36 Elaine Walker 38 Jenean Hampton 40 Alison Lundergan Grimes 42 Allison Ball 45 1 Political Bandwagon: Biographies of Kentucky Women Mary Barr Clay b. October 13, 1839 d. October 12, 1924 Birthplace: Lexington, Kentucky (Fayette County) Positions held/party affiliation • Vice President of the American Woman Suffrage Association • Vice President of the National Woman Suffrage Association • President of the American Woman Suffrage Association; 1883-? Photo Source: Biography https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Barr_Clay Mary Barr Clay was born on October 13th, 1839 to Kentucky abolitionist Cassius Marcellus Clay and Mary Jane Warfield Clay in Lexington, Kentucky. Mary Barr Clay married John Francis “Frank” Herrick of Cleveland, Ohio in 1839. They lived in Cleveland and had three sons. In 1872, Mary Barr Clay divorced Herrick, moved back to Kentucky, and took back her name – changing the names of her two youngest children to Clay as well. In 1878, Clay’s mother and father also divorced, after a tenuous marriage that included affairs and an illegitimate son on her father’s part. -

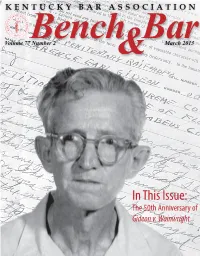

In This Issue: the 50Th Anniversary of Gideon V

In This Issue: The 50th Anniversary of Gideon v. Wainwright nationalinsurance.qxd 3/14/13 1:37 AM Page 39 OWN OCCUPATION DISABILITY INSURANCE & GROUP TERM LIFE INSURANCE SOLUTIONS Simple 1-page applications No tax return requirements to apply High quality portable benets [email protected] | 800-928-6421 ext 222 | www.niai.com Underwritten by New York Life Insurance Company, 51 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10010 on Policy Forms GMR and SIP. Features, Costs, Eligibility, Renewability, Limitations and Exclusions are detailed in the policy and in the brochure/application kit. #1212 CONTENTS_Mar.qxd 3/15/13 12:21 AM Page 1 This issue of the Kentucky Bar CONTENTS Association’s Bench & Bar was published in the month of March. 50th Anniversary of Gideon v. Wainwright Communications & Publications Committee Frances Catron Cadle, Chair, Lexington 7 Hugo’s Trumpet Paul Alley, Florence Elizabeth M. Bass, Lexington By Luke M. Milligan Zachary M.A. Becker, Frankfort James P. Dady, Bellevue 11 The History of the Right to Counsel for the Judith D. Fischer, Louisville Indigent Accused in Kentucky Cathy W. Franck, Crestwood William R. Garmer, Lexington By Robert C. Ewald, Daniel T. Goyette, P. Franklin Heaberlin, Prestonsburg Erwin W. Lewis, Edward C. Monahan Judith B. Hoge, Louisville Bernadette Z. Leveridge, Jamestown Theodore T. Myre, Jr., Louisville 19 The Cost of Representation Compared to the Cost of Eileen M. O’Brien, Lexington Incarceration: How Defense Lawyers Reduce the Richard M. Rawdon, Jr., Georgetown Costs of Running the Criminal Justice System Sandra J. Reeves, Corbin E.P. Barlow Ropp, Glasgow By John P. -

Ref. BOR-12H, Page 1 of 19 U.S

Harry Reid Harry Mason Reid (/riːd/; born December 2, 1939) is a retired Harry Reid American attorney and politician who served as a United States Senator from Nevada from 1987 to 2017. He led the Senate's Democratic Conference from 2005 to 2017 and was the Senate Majority Leader from 2007 to 2015. Reid began his public career as the city attorney for Henderson, Nevada before winning election to the Nevada Assembly in 1968. Reid's former boxing coach, Mike O'Callaghan, chose Reid as his running mate in the 1970 Nevada gubernatorial election, and Reid served as Lieutenant Governor of Nevada from 1971 to 1975. After being defeated in races for the United States Senate and the position of mayor of Las Vegas, Reid served as chairman of the Nevada Gaming Commission from 1977 to 1981. From 1983 to 1987, Reid represented Nevada's 1st district in the United States House of Representatives. Senate Majority Leader Reid won election to the United States Senate in 1986 and served in In office the Senate from 1987 to 2017. He served as the Senate Democratic January 3, 2007 – January 3, 2015 Whip from 1999 to 2005 before succeeding Tom Daschle as Senate Deputy Dick Durbin Minority Leader. The Democrats won control of the Senate after the 2006 United States Senate elections, and Reid became the Preceded by Bill Frist Senate Majority Leader in 2007. He held that position for the last Succeeded by Mitch McConnell two years of George W. Bush's presidency and the first six years of Senate Minority Leader Barack Obama's presidency. -

Congressional Record—Senate S279

January 12, 2009 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S279 amongst his Senate colleagues. He ly 11 years until January 10, this past The Senator from Tennessee. served a stint running the Democratic Saturday. He never lost an election for f Senatorial Campaign Committee. public office. Kentucky sent him to the By 1987, he had risen to become U.S. Senate four times, and he was the TRIBUTE TO MITCH MCCONNELL chairman of the Senate Rules Com- first statewide candidate to carry all Mr. ALEXANDER. Mr. President, mittee. That position put him in 120 counties. those who have been listening and charge of the inaugural ceremonies at How does a country boy from Yellow watching for the last few minutes got the Capitol for both Presidents George Creek achieve such success at the high- one good lesson on why Senator H.W. Bush in 1989 and Bill Clinton in est levels of American politics? I think MCCONNELL has been here for over 24 1993. Kentuckians were proud to see because no matter where he ended up, years. This is a day to honor him, but one of their own on the inaugural plat- Wendell Ford never forgot from where he spent virtually all of his time hon- form just footsteps away from the new he started from. Even in his final oring someone else. President. months in the Senate, he still got It is a remarkable and rare event Wendell was chairman of the Joint goose bumps every time he looked up that Senator MCCONNELL could serve Committee on Printing where he at the Capitol dome on his way to longer than Wendell Ford, the man he worked to trim the costs of Govern- work. -

Kentucky Warbler Library Special Collections

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Kentucky Warbler Library Special Collections 8-2013 Kentucky Warbler (Vol. 89, no. 3) Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_warbler Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Kentucky Warbler (Vol. 89, no. 3)" (2013). Kentucky Warbler. Paper 357. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ky_warbler/357 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Warbler by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Kentucky Warbler (Published by Kentucky Ornithological Society) VOL. 89 AUGUST 2013 NO. 3 IN THIS ISSUE IN MEMORIAM: VIRGINIA (GINNY) HENRY KINGSOLVER, Blaine R. Ferrell ...... 63 SPRING 2013 SEASON, Brainard Palmer-Ball, Jr., and Lee McNeely............................. 63 FIELD NOTE Brown-headed Nuthatches in Marshall County: A First Nesting Record for Kentucky ....................................................................................................................... 82 NEWS AND VIEWS .......................................................................................................... 87 62 THE KENTUCKY WARBLER Vol. 89 THE KENTUCKY ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY President............................................................................................. Carol Besse, Louisville Vice-President ..............................................................................Steve -

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, November 11, 1996 Volume 32ÐNumber 45 Pages 2265±2357 1 VerDate 28-OCT-97 13:32 Nov 05, 1997 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 W:\DISC\P45NO4.000 p45no4 Contents Addresses and Remarks Executive OrdersÐContinued See also Resignations and Retirements Amending Executive Order 12015, Relating to Arkansas, Little RockÐ2288, 2343 Competitive Appointments of Students California, Santa BarbaraÐ2267 Who Have Completed Approved Career- Related Work Study ProgramsÐ2355 Florida Amendments to Executive Order 12992, TampaÐ2296 Expanding and Changing the Name of the West Palm BeachÐ2300 President's Council on Counter-NarcoticsÐ Iowa, Cedar RapidsÐ2328 2349 Kentucky, LexingtonÐ2324 Louisiana, New OrleansÐ2293 Interviews With the News Media Maine, BangorÐ2312 Exchange with reporters in the Cross Halls on Massachusetts, SpringfieldÐ2308 the State FloorÐ2353 New Hampshire, ManchesterÐ2317 Proclamations New Jersey, Union TownshipÐ2305 New Mexico, Las CrucesÐ2278 To Extend Nondiscriminatory Treatment (Most-Favored-Nation Treatment) to the Ohio, ClevelandÐ2320 Products of RomaniaÐ2355 Radio addressÐ2282 Veterans DayÐ2266 South Dakota, Sioux FallsÐ2334 Texas Resignations and Retirements El PasoÐ2274 Secretary of State Warren ChristopherÐ2353 San AntonioÐ2283 Statements by the President Victory celebrations Little Rock, ArkansasÐ2343 Russia, heart bypass surgery of President National Building MuseumÐ2350 Boris YeltsinÐ2342 United Auto Workers and General Motors, White HouseÐ2348 tentative agreementÐ2293 Communications to Congress Supplementary Materials Iraq, letterÐ2339 Acts approved by the PresidentÐ2357 Prevention of importation of weapons of mass Checklist of White House press releasesÐ destruction, letterÐ2346 2356 Digest of other White House Executive Orders announcementsÐ2355 Administration of the Midway IslandsÐ2265 Nominations submitted to the SenateÐ2356 WEEKLY COMPILATION OF regulations prescribed by the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register, approved by the President (37 FR 23607; 1 CFR Part 10). -

History of the Kentucky Registry of Election Finance

HISTORY OF THE KENTUCKY REGISTRY OF ELECTION FINANCE KENTUCKY REGISTRY OF ELECTION FINANCE 140 WALNUT STREET FRANKFORT, KY 40601 Kentucky Registry of Election Finance 140 Walnut Street Frankfort, KY 40601 HISTORY The Kentucky Registry of Election Finance was created by the General Assembly in 1966 to monitor the financial activity of candidates for public office and committees formed to participate in the election process. Succeeding General Assemblies have adopted amendments to the original act and enacted regulations to support the statutes. The duties and responsibilities of the Registry are found in Chapter 121 of the Kentucky Revised Statues. The Kentucky Registry of Election Finance’s Board held their first meeting on September 13, 1966. Those present were: Frank B. Hower, Jr., Jo M. Ferguson, Jo T. Orendorf, Mrs. Adron Doran, and W. Henderson Dysard. All appointed by Governor Breathitt. On January 21, 1967 the Registry office moved into its first permanent facility located at 310 West Liberty Street, Room 400, Louisville, KY 40202. The offices of the Registry occupied that building for nine years. Then on July 1, 1976 the offices were moved to 1520 Louisville Road, Frankfort, KY 40601 where it resided for 15 years. On July 1, 1991 the offices were moved to the current address of 140 Walnut Street, Frankfort, KY 40601. THE REGISTRY’S ROLE The role of the Kentucky Registry of Election Finance is to assure the integrity of the Commonwealth's electoral process by making certain there is full public access to campaign financial data and financial disclosure reports, and by administering Kentucky's campaign finance laws.