Stop Uranium Mining!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia Clare Parker BMusSt, BA(Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Discipline of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. August 2013 ii Contents Contents ii Abstract iv Declaration vi Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Figures x A Note on Terms xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: ‘The Practice of Sound Morality’ 21 Policing Abortion and Homosexuality 24 Public Conversation 36 The Wowser State 44 Chapter 2: A Path to Abortion Law Reform 56 The 1930s: Doctors, Court Cases and Activism 57 World War II 65 The Effects of Thalidomide 70 Reform in Britain: A Seven Month Catalyst for South Australia 79 Chapter 3: The Abortion Debates 87 The Medical Profession 90 The Churches 94 Activism 102 Public Opinion and the Media 112 The Parliamentary Debates 118 Voting Patterns 129 iii Chapter 4: A Path to Homosexual Law Reform 139 Professional Publications and Prohibited Literature 140 Homosexual Visibility in Australia 150 The Death of Dr Duncan 160 Chapter 5: The Homosexuality Debates 166 Activism 167 The Churches and the Medical Profession 179 The Media and Public Opinion 185 The Parliamentary Debates 190 1973 to 1975 206 Conclusion 211 Moral Law Reform and the Public Interest 211 Progressive Reform in South Australia 220 The Slippery Slope 230 Bibliography 232 iv Abstract This thesis examines the circumstances that permitted South Australia’s pioneering legalisation of abortion and male homosexual acts in 1969 and 1972. It asks how and why, at that time in South Australian history, the state’s parliament was willing and able to relax controls over behaviours that were traditionally considered immoral. -

HON. GIZ WATSON B. 1957

PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY ADVISORY COMMITTEE AND STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA TRANSCRIPT OF AN INTERVIEW WITH HON. GIZ WATSON b. 1957 - STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA - ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION DATE OF INTERVIEW: 2015-2016 INTERVIEWER: ANNE YARDLEY TRANSCRIBER: ANNE YARDLEY DURATION: 19 HOURS REFERENCE NUMBER: OH4275 COPYRIGHT: PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA. GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS NOTE TO READER Readers of this oral history memoir should bear in mind that it is a verbatim transcript of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Parliament and the State Library are not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein; these are for the reader to judge. Bold type face indicates a difference between transcript and recording, as a result of corrections made to the transcript only, usually at the request of the person interviewed. FULL CAPITALS in the text indicate a word or words emphasised by the person interviewed. Square brackets [ ] are used for insertions not in the original tape. ii GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS CONTENTS Contents Pages Introduction 1 Interview - 1 4 - 22 Parents, family life and childhood; migrating from England; school and university studies – Penrhos/ Murdoch University; religion – Quakerism, Buddhism; countryside holidays and early appreciation of Australian environment; Anti-Vietnam marches; civil-rights movements; Activism; civil disobedience; sport; studying environmental science; Albany; studying for a trade. Interview - 2 23 - 38 Environmental issues; Campaign to Save Native Forests; non-violent Direct Action; Quakerism; Alcoa; community support and debate; Cockburn Cement; State Agreement Acts; campaign results; legitimacy of activism; “eco- warriors”; Inaugural speech . -

Women in the Federal Parliament

PAPERS ON PARLIAMENT Number 17 September 1992 Trust the Women Women in the Federal Parliament Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Senate Department. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Senate Department Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3061 The Department of the Senate acknowledges the assistance of the Department of the Parliamentary Reporting Staff. First published 1992 Reprinted 1993 Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Note This issue of Papers on Parliament brings together a collection of papers given during the first half of 1992 as part of the Senate Department's Occasional Lecture series and in conjunction with an exhibition on the history of women in the federal Parliament, entitled, Trust the Women. Also included in this issue is the address given by Senator Patricia Giles at the opening of the Trust the Women exhibition which took place on 27 February 1992. The exhibition was held in the public area at Parliament House, Canberra and will remain in place until the end of June 1993. Senator Patricia Giles has represented the Australian Labor Party for Western Australia since 1980 having served on numerous Senate committees as well as having been an inaugural member of the World Women Parliamentarians for Peace and, at one time, its President. Dr Marian Sawer is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Canberra, and has written widely on women in Australian society, including, with Marian Simms, A Woman's Place: Women and Politics in Australia. -

Influence on the U.S. Environmental Movement

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 61, Number 3, 2015, pp.414-431. Exemplars and Influences: Transnational Flows in the Environmental Movement CHRISTOPHER ROOTES Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements, School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Transnational flows of ideas are examined through consideration of Green parties, Friends of the Earth, and Earth First!, which represent, respectively, the highly institutionalised, the semi- institutionalised and the resolutely non-institutionalised dimensions of environmental activism. The focus is upon English-speaking countries: US, UK and Australia. Particular attention is paid to Australian cases, both as transmitters and recipients of examples. The influence of Australian examples on Europeans has been overstated in the case of Green parties, was negligible in the case of Friends of the Earth, but surprisingly considerable in the case of Earth First!. Non-violent direct action in Australian rainforests influenced Earth First! in both the US and UK. In each case, the flow of influence was mediated by individuals, and outcomes were shaped by the contexts of the recipients. Introduction Ideas travel. But they do not always travel in straight lines. The people who are their bearers are rarely single-minded; rather, they carry and sometimes transmit all sorts of other ideas that are in varying ways and to varying degrees discrepant one with another. Because the people who carry and transmit them are in different ways connected to various, sometimes overlapping, sometimes discrete social networks, ideas are not only transmitted in variants of their pure, original form, but they become, in these diverse transmuted forms, instantiated in social practices that are embedded in differing institutional contexts. -

Take Heart and Name WA's New Federal Seat Vallentine 2015 Marks 30 Years Since Jo Vallentine Took up Her Senate Position

Take heart and name WA’s new federal seat Vallentine 2015 marks 30 years since Jo Vallentine took up her senate position, the first person in the world to be elected on an anti-nuclear platform. What better way to acknowledge her contribution to peace, nonviolence and protecting the planet than to name a new federal seat after her? The official Australian parliament website describes Jo Vallentine in this way: Jo Vallentine was elected in 1984 to represent Western Australia in the Senate for the Nuclear Disarmament Party, running with the slogan ‘Take Heart—Vote Vallentine’. She commenced her term in July 1985 as an Independent Senator for Nuclear Disarmament, claiming in her first speech that she was the first member of any parliament in the world to be elected on this platform. When she stood for election again in 1990, she was elected as a senator for The Greens (Western Australia), and was the first Green in the Australian Senate. … During her seven years in Parliament, Vallentine was a persistent voice for peace, nuclear disarmament, Aboriginal land rights, social justice and the environment (emphasis added)i. Jo Vallentine’s parliamentary and subsequent career should be recognised in the named seat of Vallentine because: 1. Jo Vallentine was the first woman or person in several roles, in particular: The first person in the world to win a seat based on a platform of nuclear disarmament The first person to be elected to federal parliament as a Greens party politician. The Greens are now Australia’s third largest political party, yet no seat has been named after any of their political representatives 2. -

D290 Roy Macleod Collection

University of Wollongong Archives (WUA) D Collections D290 Roy MacLeod Collection Creator: Professor Roy MacLeod Historical Note: Roy MacLeod is Professor Emeritus of History, and an Honorary Associate in the History and Philosophy of Science and the Centre for International Security Studies at the University of Sydney. He was educated in History, the Biochemical Sciences, and the History of Science at Harvard University, in sociology at the London School of Economics, and in History and the History of Science at Cambridge, where he received his PhD in 1967. In recognition of his work, he has since been awarded a Doctorate of Letters from Cambridge (2001), and an honorary doctorate from the University of Bologna (2005), and has received prizes and honours from several institutions in Germany, Sweden, Belgium, and Britain. In 1971, he co-founded the quarterly journal Social Studies of Science, and was its co-editor until 1991. Between 2000 and 2008, he served as Editor in Chief of Minerva, and currently serves on the editorial boards of several other journals. He is the author or editor of twenty-five books and some 150 articles in the social history of science, medicine and technology, military history, Australian, American and European history, university history, research policy, and policy for higher education. The Nuclear Archives at Wollongong reflects the nature and content of research and graduate course work begun and led by Professor MacLeod for over three decades. The archives date from 1945, and hold much material relating to the Australian Atomic Energy Commission (AAEC), and its successor, the Australian National Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), as well as the history of uranium mining, weapons testing, environmental reportage, and nuclear diplomacy, both in Australia and around the world. -

14 Good Weekend August 15, 2009 He Easy – and Dare I Say It Tempting – Story to Write Translating About Peter Garrett Starts Something Like This

WOLVES 14 Good Weekend August 15, 2009 he easy – and dare i say it tempting – story to write Translating about Peter Garrett starts something like this. “Peter Garrett songs on the was once the bold and radical voice of two generations of Australians and at a crucial juncture in his life decided to pop stage into forsake his principles for political power. Or for political action on the irrelevance. Take your pick.” political stage We all know this story. It’s been doing the rounds for five years now, ever since Garrett agreed to throw in his lot with Labor and para- was never Tchute safely into the Sydney seat of Kingsford Smith. It’s the story, in effect, going to be of Faust, God’s favoured mortal in Goethe’s epic poem, who made his com- easy, but to his pact with the Devil – in this case the Australian Labor Party – so that he might gain ultimate influence on earth. The price, of course – his service to critics, Peter the Devil in the afterlife. Garrett has We’ve read and heard variations on this Faustian theme in newspapers, failed more across dinner tables, in online chat rooms, up-country, outback – everyone, it seems, has had a view on Australia’s federal Minister for the Environment, spectacularly Arts and Heritage, not to mention another song lyric to throw at him for than they ever his alleged hollow pretence. imagined. He’s all “power no passion”, he’s living “on his knees”, he’s “lost his voice”, he’s a “shadow” of the man he once was, he’s “seven feet of pure liability”, David Leser he’s a “galah”, “a warbling twit”, “a dead fish”, and this is his “year of living talks to the hypocritically”. -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

Ross House, 2Nd Floor Victoria

Victoria Inc. A00021219R July 2013 Ross House, 2nd Floor 247 Flinders Lane Melbourne 3000 Ph. /Fax 9654 7409 Email: [email protected] WHAT’S ON Monday 1 July UAW Darebin Group meeting 12 noon Northcote Town Hall meeting room Monday 8 July UAW Organising Committee 10.30 – 12.30 2nd floor meeting room Ross House Thursday 11 July UAW Book Group 10.30 – 12.30 2nd floor meeting room Ross House Wednesday 17 July UAW COFFEE WITH A FOCUS 10.30 – 12.30 ASYLUM SEEKERS: WHAT NOW? Speaker: Claire Nicholls Asylum Seeker Resource Centre 4th floor meeting room Ross House 247 Flinders Lane Melbourne $5 RSVP 9654 7409; email [email protected] See enclosed flyer Monday 22 July UAW Film Group A small group of members and friends meets, usually at the Nova, around mid-day. Contact the office if you would like to be notified of the film and the time. UAW Newsletter July 2013 2 SCIENTISTS’ CONSENSUS ON MAINTAINING HUMANITY’S LIFE SUPPORT Carmen Green Peter Murphy from the Search Foundation (the Social Education, Action and Research Concerning Humanity Foundation) http://www.search.org.au/ has forwarded an important statement on climate change to the UAW for our endorsement with the following comment: Dear Climate network friends, This Scientists’ consensus statement is now open for scientists and any members of the public to voice their support. It brings together scientific reasoning on climate change and other pressures on our planet, and it would be great to have Australian voices supporting it. At our June meeting, the UAW’s Organising Committee discussed the Scientist’s consensus statement on climate change and encourages members to endorse this vital statement. -

Reinventing Political Institutions

Women, Pre-selection and Merit: Who Decides? Women, Pre-selection and Merit: Who Decides? Senator the Hon. Margaret Reynolds Many Australian women would assume that the greatest barrier to women’s participation in parliament is attracting sufficient votes to be elected. However, such reasoning ignores the reality of party political systems and the degree to which pre-selection of candidates is carefully controlled by the party power brokers, usually men. Pre-selection methods vary between and within parties, but the situation for women as candidates is comparable, in that the first hurdle to political representation is actually within the Australian party structure, where a dominant male culture still prevails, regardless of the fundamental and political ideology. The hurdles for women to gain election to legislative positions in Australia are mainly those that take place within ‘the secret garden of politics’— within party selectorate hierarchies…[which] tolerate the continuing advantages of incumbency for men.1 In 1977, a Labor candidate in New South Wales, Ann Conlon, described the landscape of political parties as that of tribal territory. She said: ‘Inside it the ruling group resides and rules, occasionally permitting certain outsiders the pleasure.’2 1 I. McAllister, Political Behaviour: Citizens, Parties and Elites in Australia, Longman, Melbourne, 1992, p.225. 2 A. Conlon, ‘"Women in Politics", A Personal Viewpoint’, The Australian Quarterly, September, 1977, vol.49, no.3, p.14. 31 Reinventing Political Institutions Certainly, the present gender imbalance in Australia’s federal and state parliamentary representation—since Australia led the way in women’s electoral reform—would seem to reinforce this view of women as ‘outsiders’ with no major political party having an enviable record in endorsing women candidates. -

Asylum Seekers and Australian Politics, 1996-2007

ASYLUM SEEKERS AND AUSTRALIAN POLITICS, 1996-2007 Bette D. Wright, BA(Hons), MA(Int St) Discipline of Politics & International Studies (POLIS) School of History and Politics The University of Adelaide, South Australia A Thesis Presented to the School of History and Politics In the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Contents DECLARATION ................................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. v CHAPTER 1: CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK .................................................................. 1 Sovereignty, the nation-state and stateless people ............................................................. 1 Nationalism and Identity .................................................................................................. 11 Citizenship, Inclusion and Exclusion ............................................................................... 17 Justice and human rights .................................................................................................. 20 CHAPTER 2: REFUGEE ISSUES & THEORETICAL REFLECTIONS ......................... 30 Who -

Collection Name

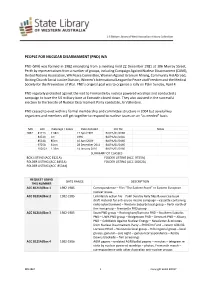

PEOPLE FOR NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT (PND) WA PND (WA) was formed in 1982 emanating from a meeting held 22 December 1981 at 306 Murray Street, Perth by representatives from a number of groups, including Campaign Against Nuclear Disarmament (CANE), United Nations Association, WA Peace Committee, Women Against Uranium Mining, Community Aid Abroad, Uniting Church Social Justice Division, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the Medical Society for the Prevention of War. PND’s original goal was to organise a rally on Palm Sunday, April 4. PND regularly protested against the visit to Fremantle by nuclear powered warships and conducted a campaign to have the US military base at Exmouth closed down. They also assisted in the successful election to the Senate of Nuclear Disarmament Party candidate, Jo Vallentine. PND ceased to exist within a formal membership and committee structure in 2004 but several key organizers and members still get together to respond to nuclear issues on an “as needed” basis. MN ACC meterage / boxes Date donated CIU file Notes 2867 8121A 2.38m 17 April 1991 BA/PA/01/0166 8451A 1m 1996 BA/PA/01/0166 8534A 85cm 16 April 2009 BA/PA/01/0166 9725A 61cm 28 December 2011 BA/PA/01/0166 10202A 1.36m 14 January 2016 BA/PA/01/0166 SUMMARY OF CLASSES BOX LISTING (ACC 8121A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 9725A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 8451A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 10202A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 8534A) REQUEST USING DATE RANGE DESCRIPTION THIS NUMBER ACC 8121A/Box 1 1982-1985 Correspondence – File; “The Eastern Front” re Eastern European nuclear