Arxiv:1810.11411V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 26 Oct 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zheng31sympa.Pdf

Proceedings of the Combustion Institute Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 31 (2007) 1215–1222 www.elsevier.com/locate/proci High temperature ignition and combustion enhancement by dimethyl ether addition to methane–air mixtures q Zheng Chen, Xiao Qin, Yiguang Ju *, Zhenwei Zhao, Marcos Chaos, Frederick L. Dryer Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA Abstract The effects of dimethyl ether (DME) addition on the high temperature ignition and burning properties of methane–air mixtures were studied experimentally and numerically. The results showed that for a homo- geneous system, a small amount of DME addition to methane resulted in a significant reduction in the high temperature ignition delay. The ignition enhancement effect by DME addition was found to exceed that possible with equivalent amounts of hydrogen addition, and it was investigated by using radical pool growth and computational singular perturbation analysis. For a non-premixed methane–air system, it was found that two different ignition enhancement regimes exist: a kinetic limited regime and a transport limited regime. In contrast to the dramatic ignition enhancement in the kinetic limited regime, the ignition enhancement in the transport limited regime was significantly less effective. Furthermore, laminar flame speeds as well as Markstein lengths were experimentally measured for methane–air flames with DME addi- tion. The results showed that the flame speed increases almost linearly with DME addition. However, the Markstein length and the Lewis number of the binary fuel change dramatically at small DME concentra- tions. Moreover, comparison between experiments and numerical simulations showed that only the most recent DME mechanism well reproduced the flame speeds of both DME–air and CH4–air flames. -

Ethylene Glycol Dimethyl Ether.Pdf

SIGMA-ALDRICH sigma-aldrich.com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 4.0 Revision Date 03/14/2010 Print Date 09/08/2010 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : 1,2-Dimethoxyethane Product Number : 259527 Brand : Sigma-Aldrich Company : Sigma-Aldrich 3050 Spruce Street SAINT LOUIS MO 63103 USA Telephone : +18003255832 Fax : +18003255052 Emergency Phone # : (314) 776-6555 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview OSHA Hazards Flammable liquid, Target Organ Effect, Reproductive hazard Target Organs Liver, Kidney, Blood, Central nervous system, Female reproductive system., Male reproductive system. GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Danger Hazard statement(s) H225 Highly flammable liquid and vapour. H303 May be harmful if swallowed. H332 Harmful if inhaled. H360 May damage fertility or the unborn child. Precautionary statement(s) P201 Obtain special instructions before use. P210 Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces. - No smoking. P308 + P313 IF exposed or concerned: Get medical advice/attention. HMIS Classification Health hazard: 1 Chronic Health Hazard: * Flammability: 3 Physical hazards: 0 NFPA Rating Health hazard: 0 Fire: 3 Reactivity Hazard: 0 Potential Health Effects Inhalation May be harmful if inhaled. May cause respiratory tract irritation. Skin May be harmful if absorbed through skin. May cause skin irritation. Eyes May cause eye irritation. Sigma-Aldrich - 259527 Page 1 of 6 Ingestion May be harmful if swallowed. 3. COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Synonyms : Monoglyme Dimethylglycol mono-Glyme Ethylene glycol dimethyl ether Formula : C4H10O2 Molecular Weight : 90.12 g/mol CAS-No. EC-No. Index-No. Concentration Ethylene glycol dimethyl ether 110-71-4 203-794-9 603-031-00-3 - 4. -

Selective Carbonylation of Dimethyl Ether to Methyl Acetate on Ferrierite

Catalysis Communications 75 (2016) 28–31 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Catalysis Communications journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/catcom Short communication Selective carbonylation of dimethyl ether to methyl acetate on Ferrierite So Young Park a, Chae-Ho Shin b,JongWookBaea,⁎ a School of Chemical Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU), Suwon, Gyeonggi-do 440-746, Republic of Korea b Department of Chemical Engineering, Chungbuk National University (CNU), Cheongju, Chungbuk 361-763, Republic of Korea article info abstract Article history: Synthesis of methyl acetate (MA) by carbonylation of dimethyl ether (DME) was investigated using laboratory- Received 19 August 2015 made H-form Ferrierite (FER) zeolite with different Si/Al molar ratios. The synthesized H-FER with a Si/Al ratio of Received in revised form 6 November 2015 12 (FER(12)) revealed a higher DME conversion as well as MA selectivity. The observed higher catalytic perfor- Accepted 9 December 2015 mance on the FER(12) was mainly attributed to a higher ratio of Bronsted to Lewis acid sites as well as the higher Available online 10 December 2015 crystallinity with the less coke formation. The superior properties of the FER(12) having a higher ratio of Bronsted fi Keywords: to Lewis acid sites and crystallinity ef ciently suppressed the formation of inactive coke precursors. Carbonylation © 2015 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Dimethyl ether Methyl acetate Ferrierite Coke formation 1. Introduction can be finally regenerated by forming an adsorbed methyl group [12, 13]. Interestingly, the micropores of the H-form Ferrierite (H-FER), Carbonylation reaction of dimethyl ether (DME) with CO has been which has one-dimensional channels of 8-MR with perpendicularly largely investigated to selectively synthesize an important petrochemi- intersected channels of 10-MR structures, seem to be effective for cal intermediate or alternative clean fuels [1,2]. -

Combustion and Emissions Characteristics of a Compression-Ignition Engine Using Ammonia-DME Mixtures Christopher Wolfgang Gross Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 Combustion and emissions characteristics of a compression-ignition engine using ammonia-DME mixtures Christopher Wolfgang Gross Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Gross, Christopher Wolfgang, "Combustion and emissions characteristics of a compression-ignition engine using ammonia-DME mixtures" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12589. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12589 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Combustion and emissions characteristics of a compression- ignition engine using ammonia-DME mixtures by Christopher W. Gross A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Mechanical Engineering Program of Study Committee: Song-Charng Kong, Major Professor Terrence Meyer Stuart Birrell Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Christopher W. Gross, 2012. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents List of Figures ........................................................................................................................ -

CO2 Recycling to Dimethyl Ether: State-Of-The-Art and Perspectives

molecules Review CO2 Recycling to Dimethyl Ether: State-of-the-Art and Perspectives Enrico Catizzone 1,* ID , Giuseppe Bonura 2 ID , Massimo Migliori 1, Francesco Frusteri 2 and Girolamo Giordano 1 1 Department of Environmental and Chemical Engineering, University of Calabria, Via P. Bucci, 87036 Rende (CS), Italy; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (G.G.) 2 CNR-ITAE “Nicola Giordano”, Via S. Lucia Sopra Contesse 5, 98126 Messina, Italy; [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (F.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-098-449-6669 Received: 13 November 2017; Accepted: 22 December 2017; Published: 24 December 2017 Abstract: This review reports recent achievements in dimethyl ether (DME) synthesis via CO2 hydrogenation. This gas-phase process could be considered as a promising alternative for carbon dioxide recycling toward a (bio)fuel as DME. In this view, the production of DME from catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 appears as a technology able to face also the ever-increasing demand for alternative, environmentally-friendly fuels and energy carriers. Basic considerations on thermodynamic aspects controlling DME production from CO2 are presented along with a survey of the most innovative catalytic systems developed in this field. During the last years, special attention has been paid to the role of zeolite-based catalysts, either in the methanol-to-DME dehydration step or in the one-pot CO2-to-DME hydrogenation. Overall, the productivity of DME was shown to be dependent on several catalyst features, related not only to the metal-oxide phase—responsible for CO2 activation/hydrogenation—but also to specific properties of the zeolites (i.e., topology, porosity, specific surface area, acidity, interaction with active metals, distributions of metal particles, . -

Comparing Properties of Isomers

COMPARING PROPERTIES OF ISOMERS Sometimes there is more than one way to connect a given group of atoms into a molecular structure. Given the formula C2H6O, two different isomers are possible: methyl ether and ethanol. They have the same formula but different structures. The word, "isomer", is from the Greek, meaning "same things", referring to their identical content. However, isomers often have very different physical and biological properties. These two compounds have different physical properties, as you can see in the table below. compound melting pt, ° C boiling pt, ° C dimethyl ether -138 -25 ethanol -117 78 Remember, typical room temperature is about 25 °C. That means that at room temperature, dimethyl ether is a gas, because it is above its boiling point. Ethanol, on the other hand, is a liquid at room temperature. Ethanol at that temperature is well above its freezing point but has not yet reached its boiling point. Why is that? What is the origin for the differences in physical properties between these two, similar compounds, one of which is a gas at room temperature while the other is a liquid? Both contain carbon-hydrogen and carbon-oxygen bonds. The ethanol also contains a carbon-carbon bond and an oxygen-hydrogen bond. Certain bonds, or groups of bonds, confer specific behaviors on the compounds in which they are found. For instance, when an OH group is found in an organic compound, it can make the compound moderately acidic. It also makes the compound a little more likely to be a solid or liquid rather than a gas. -

Astrochemistry of Dimethyl Ether

A&A 445, 197–204 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20053651 & c ESO 2005 Astrophysics Astrochemistry of dimethyl ether Z. Peeters1, S. D. Rodgers2,S.B.Charnley2, L. Schriver-Mazzuoli3 ,A.Schriver3,J.V.Keane2, and P. Ehrenfreund1 1 Leiden Institute of Chemistry, PO Box 9502, 2300 RA, Leiden, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 2 Space Science and Astrobiology Division, NASA Ames Research Center, MS 245-3, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 3 Université P. et M. Curie, Department of Physical Chemistry, Case 22, 4 place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France Received 17 June 2005 / Accepted 31 August 2005 ABSTRACT Dimethyl ether (DME, CH3OCH3) is one of the largest organic molecules detected in the interstellar gas and shows high abundances in star- forming regions, known as hot molecular cores. The observed DME might be formed on grains or by secondary gas phase reactions from a precursor molecule, which in turn was sublimed into the gas phase from the grain surface. Studies on the stability and degradation pathways of DME therefore provide important constraints on the evolutionary cycle of large organic molecules and chemical pathways in the interstellar medium. We studied the UV photodestruction rate of DME in a solid argon matrix. DME was destroyed with a half-life of 54 seconds under laboratory conditions, which corresponds to 8.3 × 105 years in a dense cloud. We discuss the UV photochemistry of DME in the context of two issues: its formation mechanism and its chemistry in hot cores. Chemical models of shielded hot core regions indicate that UV photodestruction is relatively unimportant for DME, even by the internally-generated radiation field. -

Dimethyl Ether

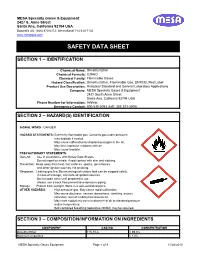

MESA Specialty Gases & Equipment 2427 S. Anne Street Santa Ana, California 92704 USA Domestic US: (866) 470-6372; International 714-434-7102 www.mesagas.com SAFETY DATA SHEET SECTION 1 – IDENTIFICATION Chemical Name: Dimethyl Ether Chemical Formula: C2H6O Chemical Family: Flammable Gases Hazard Classification: Dimethyl Ether, Flammable Gas, UN1033, Red Label Product Use Description: Analytical Standard and General Laboratory Applications Company: MESA Specialty Gases & Equipment 2427 South Anne Street Santa Ana, California 92704 USA Phone Number for Information: Infotrac Emergency Contact: 800-535-5053 (Int’l: 352-323-3500) SECTION 2 – HAZARD(S) IDENTIFICATION SIGNAL WORD - DANGER HAZARD STATEMENTS: Extremely flammable gas. Contains gas under pressure; may explode if heated. May cause suffocation by displacing oxygen in the air. May form explosive mixtures with air. May cause frostbite. PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS: General: Use in accordance with Safety Data Sheets. Do not ingest or inhale. Avoid contact with skin and clothing. Prevention: Keep away from heat, hot surfaces, sparks, open flames, and other ignition sources. No smoking. Response: Leaking gas fire: Do not extinguish unless leak can be stopped safely. In case of leakage, eliminate all ignition sources. Do not open valve until prepared to use. Always use a back flow preventative device in piping. Storage: Protect from sunlight. Store in a well-ventilated place. OTHER HAZARDS: High pressure gas. May cause rapid suffocation. May cause dizziness, nausea, drowsiness, vomiting, excess salivation, loss of mobility/consciousness. May react explosively even in absence of air at elevated pressure and/or temperature. Self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) may be required. SECTION 3 – COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS COMPONENT CAS NO. -

Dimethyl Sulfide-Dimethyl Ether and Ethylene Oxide-Ethylene Sulfide Complexes In- Vestigated by Fourier Transform Microwave Spectroscopy and Ab Initio Calculation

DIMETHYL SULFIDE-DIMETHYL ETHER AND ETHYLENE OXIDE-ETHYLENE SULFIDE COMPLEXES IN- VESTIGATED BY FOURIER TRANSFORM MICROWAVE SPECTROSCOPY AND AB INITIO CALCULATION YOSHIYUKI KAWASHIMA, YOSHIO TATAMITANI, TAKAYUKI MASE, Applied Chemistry, Kanagawa Institute of Technology, Atsugi, Japan; EIZI HIROTA, The Central Office, The Graduate University for Ad- vanced Studies, Hayama, Kanagawa, Japan. The ground-state rotational spectra of the dimethyl sulfide-dimethyl ether (DMS-DME) and the ethylene oxide and ethylene sulfide (EO-ES) complexes were observed by Fourier transform microwave spectroscopy, and a-type and c-type transitions were assigned for the normal, 34S, and three 13C species of the DMS-DME and a-type and b-type rotational transitions for the normal, 34S, and two 13C species of the EO-ES. The observed transitions were analyzed by using an S-reduced asymmetric-top rotational Hamiltonian. The rotational parameters thus derived for the DMS-DME were found consistent with a structure of Cs symmetry with the DMS bound to the DME by two C-H(DMS)—O and one S—H- C(DME) hydrogen bonds. The barrier height V 3 to internal rotation of the ”free” methyl group in the DME was determined to be 915.4 (23) cm−1, which is smaller than that of the DME monomer, 951.72 (70) cm−1,a and larger than that of the DME dimer, 785.4 (52) cm−1.b For the EO-ES complex the observed data were interpreted in the terms of an antiparallel Cs geometry with the EO bound to the ES by two C-H(ES)—O and two S—H-C(EO) hydrogen bonds. -

Dimethyl Ether, a Review of Production Processes and a Modeling of the Indirect Route

Liege University PROJ0012-1, 2019-2020 Dimethyl ether, A review of production processes and a modeling of the indirect route Cyril Fortin, Nicolas Gianfolcaro, Rachel Gonzalez, Justine Lohest, Antoine Lonneux, Pauline Mordant, Ariane Kesnelle Ndong Siliki, Thomas Peiffer, Romain Renson, Claire Schmitz Abstract Dimethyl ether (DME) can be considered as a potential substitute to traditional fuels and, thus, receives a great industrial interest. This paper exposes the two main DME production processes: the direct route, where DME is directly produced from syngas and the indirect route which involves the upstream methanol production. This paper also presents a modeled DME production plant (through indirect route) of a capacity of 116 kton/yr. This simulation was performed in Aspen Plus software using the UNIQUAC thermodynamic model. DME is produced tough the dehydration of methanol under g −Al2O3 catalyst in a adiabatic fixed-bed reactor. The proposed model allows to reach a DME yield and purity of respectively 93.1 % and 99.6 mol %. A cost analysis was performed. OPEX and CAPEX are evaluated to 66,987 k$/yr and 3,780 k$. The economical balance shows that benefices of the production plant widely depend on the price of the methanol feed stream. A life cycle analysis of the process shows a good agreement between the modeled process and Ecoinvent data base. A literature review was also performed to investigate other ways to produce DME. Improvements can be achieved within the indirect route. The literature review shows that using silica embedded g − Al2O3 or zeolite catalyst can enhance the DME conversion up to 86% and 94% respectively. -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,744,542 Martz Et Al

USOO5744542A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,744,542 Martz et al. 45 Date of Patent: Apr. 28, 1998 54 EMULSFERS AND THER USE IN WATER 5, 191012 3/1993 Markusch et al. ...................... 524/59 DSPERSIBLE POLY SOCYANATE 5, 1944.87 3/1993 Jacobs ............... ... 524/840 COMPOSITIONS 5,200,489 4/1993 Jacobs et al. 528/49 5202,377 4/1993 Thorne et al. .......................... 524,591 5,252,696 10/1993 Laas et al. ........ ........ 528/49 75 Inventors: Jonathan T. Martz, Shaler Township, 5296,160 3/1994 Tirpak et al. ..... ... 252/82.2 Allegheny County; Joseph M. Carney, 5,300,556 4/1994 Tirpak et al. .......................... 524/591 Reserve Township, Allegheny County; 5,331,039 7/1994 Blum et al. ....... ... 524/SO Robert E. Jennings, New Sewickley 5,373,050 12/1994 Morikawa et al. ..................... 524,591 Township, Beaver County; Karen D. 5,380,792 l/1995 Renk ....................................... 524840 Donnelly, Hampton Township, 5,387,367 2/1995 Haeberde et al. 252/182,22 Allegheny County, all of Pa. 5,389,718 2/1995 Potter et al. ............................ 524,591 5,389,720 2/1995 Markusch et al. ...................... 524,839 73 Assignee: PPG Industries, Inc., Pittsburgh, Pa. FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 21 Appl. No.: 744,566 20854.95 6/1993 Canada. 2088805 8/1993 Canada. 22 Filed: Nov. 6, 1996 63-2 16070 12/1989 Japan. 1-2 16070 4/1991 Japan. Related U.S. Application Data OTHER PUBLICATIONS 63 Continuation of Ser. No. 411253, Mar. 27, 1995, aban doned. Isocyanates, Organic; Encyclopedia of Chemical Technol ogy, vol. 13, pp. 789-817. -

Glycol Ether Guidance

Glycol Ethers Guidance (7/26/2005) “Glycol Ethers” is a hazardous air pollutant defined in Iowa Administrative Code (567) rule 22.100 as follows: 567 IAC 22.100, definition of “hazardous air pollutant”: Glycol Ethers2, except CAS #111-76-2, ethylene glycol mono-butyl ether, also known as EGBE or 2- Butoxyethanol 2 Includes mono- and di-ethers of ethylene glycol, diethylene glycol, and triethylene glycol R(OCH2CH2)n- OR’ where n=1, 2, or 3; R=alkyl or aryl groups; R’=R,H, or groups which, when removed, yield glycol ethers with the structure R(OCH2CH)n-OH. Polymers are excluded from the glycol category. There are literally thousands of compounds included in the glycol ethers category. The definition of glycol ethers in the Iowa Administrative Code is taken directly from 40 CFR 63.21, and is consistent with the definition for certain glycol ethers used in Toxics Release Inventory program. For this reason, the Iowa DNR suggests using the EPA document entitled “Toxics Release Inventory: List of Toxic Chemicals Within the Glycol Ethers Category (December 2000)” for a listing of glycol ethers. This document is available at http://www.epa.gov/ttn/atw/glycol2000.pdf. Common Glycol Ethers* Delisted Glycol Ethers Chemical Name CAS Number Chemical Name CAS Number Diethylene glycol dimethyl ether 111-96-6 111-76-2 Ethylene glycol mono-butyl Diethylene glycol monobutyl ether acetate 124-17-4 Delisted ether, also known as EGBE or 2- Diethylene glycol monobutyl ether 112-34-5 11/29/2004 Butoxyethanol Diethylene glycol monoethyl ether acetate 112-15-2