Philosophy of Law in the Arctic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Actas Del Vi Simposio De La Red Latinoamericana De Estudios Sobre Imagen, Identidad Y Territorio

ACTAS DEL VI SIMPOSIO DE LA RED LATINOAMERICANA DE ESTUDIOS SOBRE IMAGEN, IDENTIDAD Y TERRITORIO “ESCENARIOS DE INQUIETUD. CIUDADES, POÉTICAS, POLÍTICAS” 14, 15 Y 16 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2016 MICAELA CUESTA M. FERNANDA GONZÁLEZ MARÍA STEGMAYER (COMPS.) 2 Cuesta, Micaela Actas del VI Simposio de la Red Latinoamericana de estudios sobre Imagen, Identidad y Territorio : escenarios de inquietud : ciudades, poéticas, políticas / Micaela Cuesta ; María Fernanda González ; María Stegmayer. - 1a ed compendiada. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Departamento de Publicaciones de la Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad de Buenos Aires. Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani - UBA, 2016. Libro digital, PDF Archivo Digital: descarga y online ISBN 978-987-3810-27-5 1. Identidad. 2. Imagen. 3. Actas de Congresos. I. González, María Fernanda II. Stegmayer, María III. Título CDD 306 3 ÍNDICE Presentación .............................................................................................................................. 5 Ciudades y memorias Sesión de debates I: Cuerpo y espacio Ciudades performativas: Teatralidad, memoria y experiencia..................................................... 11 Lorena Verzero Fioravante e o vazio: o desenho como estratégia de ausência................................................... 21 Eduardo Vieira da Cunha Percepción geográfica del espacio y los cuatro elementos: Reflexión sobre una interfaz entre fenomenología y astrología......................................................................................................... -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Page numbers in italic refer to tables, and those in bold to figures. accretionary orogens, defined 23 Namaqua-Natal Orogen 435-8 Africa, East SW Angola and NW Botswana 442 Congo-Sat Francisco Craton 4, 5, 35, 45-6, 49, 64 Umkondo Igneous Province 438-9 palaeomagnetic poles at 1100-700 Ma 37 Pan-African orogenic belts (650-450 Ma) 442-50 East African(-Antarctic) Orogen Damara-Lufilian Arc-Zambezi Belt 3, 435, accretion and deformation, Arabian-Nubian Shield 442-50 (ANS) 327-61 Katangan basaltic rocks 443,446 continuation of East Antarctic Orogen 263 Mwembeshi Shear Zone 442 E/W Gondwana suture 263-5 Neoproterozoic basin evolution and seafloor evolution 357-8 spreading 445-6 extensional collapse in DML 271-87 orogenesis 446-51 deformations 283-5 Ubendian and Kibaran Belts 445 Heimefront Shear Zone, DML 208,251, 252-3, within-plate magmatism and basin initiation 443-5 284, 415,417 Zambezi Belt 27,415 structural section, Neoproterozoic deformation, Zambezi Orogen 3, 5 Madagascar 365-72 Zambezi-Damara Belt 65, 67, 442-50 see also Arabian-Nubian Shield (ANS); Zimbabwe Belt, ophiolites 27 Mozambique Belt Zimbabwe Craton 427,433 Mozambique Belt evolution 60-1,291, 401-25 Zimbabwe-Kapvaal-Grunehogna Craton 42, 208, 250, carbonates 405.6 272-3 Dronning Mand Land 62-3 see also Pan-African eclogites and ophiolites 406-7 Africa, West 40-1 isotopic data Amazonia-Rio de la Plata megacraton 2-3, 40-1 crystallization and metamorphic ages 407-11 Birimian Orogen 24 Sm-Nd (T DM) 411-14 A1-Jifn Basin see Najd Fault System lithologies 402-7 Albany-Fraser-Wilkes -

World Heritage Cultural Landscapes a Handbook for Conservation and Management

World Heritage papers26 World Heritage Cultural Landscapes A Handbook for Conservation and Management World Heritage Cultural Landscapes A Handbook for Conservation and Management Nora Mitchell, Mechtild Rössler, Pierre-Marie Tricaud (Authors/Ed.) Drafting group Nora Mitchell, Mechtild Rössler, Pierre-Marie Tricaud Editorial Assistant Christine Delsol Contributors Carmen Añón Feliú Alessandro Balsamo* Francesco Bandarin* Disclaimer Henry Cleere The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of Viera Dvoráková the authors and are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not Peter Fowler commit the Organization. Eva Horsáková Jane Lennon The designations employed and the presentation of material in this Katri Lisitzin publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever Kerstin Manz* on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, Nora Mitchell territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delim- Meryl Oliver itation of its frontiers or boundaries. Saúl Alcántara Onofre John Rodger Published in November 2009 by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre Mechtild Rossler* Anna Sidorenko* The publication of this volume was financed by the Netherlands Herbert Stovel Fund-in-Trust. Pierre-Marie Tricaud Herman van Hooff* Augusto Villalon World Heritage Centre Christopher Young UNESCO (* UNESCO staff) 7, place de Fontenoy 75352 Paris 07 SP France Coordination of the World Heritage Paper Series Tel. : 33 (0)1 45 68 15 71 Vesna Vujicic Lugassy Fax: 33 (0)1 45 68 55 70 Website: http://whc.unesco.org -

Acta 15 Pass

00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 1 CATHOLIC SOCIAL DOCTRINE AND HUMAN RIGHTS 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 2 Address The Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences Casina Pio IV, 00120 Vatican City Tel.: +39 0669881441 – Fax: +39 0669885218 E-mail: [email protected] 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 3 THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Acta 15 CATHOLIC SOCIAL DOCTRINE AND HUMAN RIGHTS the PROCEEDINGS of the 15th Plenary Session 1-5 May 2009 • Casina Pio IV Edited by Roland Minnerath Ombretta Fumagalli Carulli Vittorio Possenti IA SCIEN M T E IA D R A V C M A S A O I C C I I A F I L T I V N M O P VATICAN CITY 2010 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 4 The opinions expressed with absolute freedom during the presentation of the papers of this plenary session, although published by the Academy, represent only the points of view of the participants and not those of the Academy. 978-88-86726-25-2 © Copyright 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, photocopying or otherwise without the expressed written permission of the publisher. THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES VATICAN CITY 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 5 His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 6 Participants in the conference hall of the Casina Pio IV 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 7 Participants of the 15th Plenary Session 00_Prima Parte_Acta15:PrimaParte-Acta917/02/1008:35Pagina8 His Holiness Benedict XVI with the Participants of the 15th Plenary Session 00_Prima Parte_Acta 15:Prima Parte-Acta9 17/02/10 08:35 Pagina 9 CONTENTS Address of the Holy Father to the Participants......................................... -

Ai-/Ais-Richtersveld Transfrontier Park “Since This Spectacular Area Is Undeveloped and There Is So Much to Explore, You Feel As If No One Else Has Ever Been Here

/Ai-/Ais-Richtersveld Transfrontier Park “Since this spectacular area is undeveloped and there is so much to explore, you feel as if no one else has ever been here. That the park is yours alone to discover.” Wayne Handley, Senior Ranger, /Ai-/Ais Richtersveld Republic of Namibia Transfrontier Park, Ministry of Environment and Tourism Ministry of Environment and Tourism Discover the /Ai-/Ais Richtersveld 550 metres above. Klipspringer bound up the cliffs and moun- Transfrontier Park tain chats drink from pools left behind from when the river last Experience wilderness on a scale unimaginable. Stand at the edge flowed. Ancient rock formations and isolation add to the sense of of the largest natural gorge in Africa, and the second-largest can- timelessness and elation that mark this challenging hike. yon in the world, the Fish River Canyon. Revel in the dramatic views from Hell’s Corner where it is almost possible to imagine For 4x4 enthusiasts, drives along the rugged eastern rim of the the dramatic natural forces that shaped the canyon. Today the canyon afford stunning views across the canyon from Hell’s /Ai-/Ais Richtersveld Transfrontier Park protects a vast area that Corner and Sulphur Springs vantage points. One hundred ki- crosses the South African border to encompass one of the richest lometres further south, another more leisurely route winds botanical hot spots in the world, the Succulent Karoo biome. along the edge of the Orange River, where masses of water are framed by towering black mountains. Strewn with immense boulders, the bed of the Fish River is also home to one of the most exhilarating adventures in Southern Everywhere there are rare plants, including 100 endemic suc- Africa, the five-day, 90-kilometre Fish River Canyon hiking trail, culents and over 1 600 other plant species, illusive rare animals, for which you need a hiking permit. -

Nomadic Desert Birds

Nomadic Desert Birds Bearbeitet von W. Richard J Dean 1. Auflage 2003. Buch. x, 185 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 540 40393 7 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 1010 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Chemie, Biowissenschaften, Agrarwissenschaften > Biowissenschaften allgemein > Terrestrische Ökologie Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. CHAPTER 1 Introduction There are two basic strategies for coping with life in the desert: (1) to be res- ident and sedentary and by behavioural or physiological tactics able to withstand extremes of heat and cold, lack of water and fluctuations in the availability of food and plant cover, or (2) to be a migrant, and to oppor- tunistically or seasonally move to where these resources are available. For at least one group of animals, the avifauna, both strategies have their advan- tages and disadvantages (Andersson 1980). For sedentary, resident species the advantages are an intimate knowledge of the patch in which they live,and for some a permanent home, but the quality of life in the patch is variable, and there is no escape from stochastic weather events that may temporarily transform the patch into a place where making a living becomes very hard indeed. For species that move, the advantages are to be able to find a patch where resources are at least in reasonable supply,even though there are asso- ciated costs – the energetic costs of moving and maintaining water balance (Maclean 1996), the difficulties of finding patches that offer such resources, increased competition at the patches and the lack of a permanent territory and/or pair bond. -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

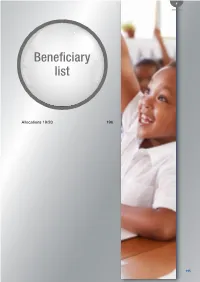

Beneficiary List

F Beneciary list Beneciary list Allocations 19/20 196 National Lotteries Commission Integrated Report 2019/2020 195 ALLOCATIONS 19/20 Date Sector Province Proj No. Name Amount 11-Apr-19 Arts GP 73807 CHILDREN’S RIGHTS VISION (SA) 701 899,00 15-Apr-19 Arts LP M12787 KHENSANI NYANGO FOUNDATION 2 500 000,00 15-Apr-19 Sports GP 32339 United Cricket Board 2 000 800,00 23-Apr-19 Arts EC M12795 OKUMYOLI DEVELOPMENT CENTER 283 000,00 23-Apr-19 Arts KZN M12816 CARL WILHELM POSSELT ORGANISATION 343 000,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12975 MANYAKATANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 200 000,00 24-Apr-19 Arts WC M13008 ACTOR TOOLBOX 286 900,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12862 QUEEN OF RAIN ORPHANAGE HOME 321 005,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12941 GO BACK TO OUR ROOTS 351 025,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12835 LAEVELD NATIONALE KUNSTEFEES 1 903 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities FS M12924 HAND OF HANDS 5 000 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities KZN M13275 SIPHILISIWE 5 000 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities EC M13275 SIPHILISIWE 5 000 000,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13031 ABAFAZI BENGOMA 184 500,00 30-Apr-19 Arts WC M12945 HOOD HOP AFRICA 330 360,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13046 BORN TWO PROSPER 340 884,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13021 SA INDUSTRIAL THEATRE OF DISABILITY 1 509 500,00 30-Apr-19 Arts EC M12850 NATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 3 000 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports MP M12841 Flying Birds Handball Club 126 630,00 30-Apr-19 Sports KZN M12879 Ferry Stars Football Club 128 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports WC M12848 Blakes Rugby Football Club 147 961,00 30-Apr-19 Sports WC M12930 Riverside Golf Club 200 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports MP M12809 Mpumalanga Rugby -

Rastros2 Do Sem-Nome Que O Diga3

! MANUAL TEÓRICO-PRÁTICO DE ARTES DRÁSTICAS TOMO VIII DO EXPERIENCIAR VOLUME II1 ENSAIOS CAPIROTOS 2014 1 Obragem do Grupo de Pesquisa Modernidade e Cultura (GPMC) / Instituto de Pesquisa e Planejamento Urbano e Regional (IPPUR) / Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). !2 CAPUT DO MANUAL Artes drásticas, neste Manual, são artes ditas não positivas no sentido hegeliano, ou seja, que escapam a qualquer plano de legitimação ou valoração determinada heteronomamente pelo poder instituído ou praticado. Artes drásticas, assim, a esses poderes, ou às suas concernentes razões apolíneas, não se constituem como artes lícitas. São inúteis. Rabiscos, garatujas, ruídos sem sentido ou lógica. Paradoxalmente, aqui são valoradas como desúteis, como artes que não afirmam e nem operam premidas por quaisquer exigências externas de eficiência _prazos, urgências, medidas, precisão, forma padrão_, mas que primam pelas afectações poiéticas que possam suscitar. São artes que se manifestam em sua drasticidade, na pura superfície de seu expressar-se e no tempo de um presente que nunca se presentifica, enquanto evidenciação de devires sem início ou fim ou trajetória ou direção fixas. São artes do revolucionar-se, de um obrar louco que inventa em suas criações as próprias e momentâneas regras de seu obrar. São artes cujas criações são sempre e necessariamente de múltiplos e difusos autores, mesmo quando agenciadas por um único indivíduo, persona que se faz singular nesse próprio obrar. São artes que, assim !3 sendo, autorizam-se ao roubo explícito e escancarado como modo poiético próprio. !4 ! !5 I RASTROS2 DO SEM-NOME QUE O DIGA3 ou PISTAS ou DESNORTEAMENTOS ou PRA NÃO DIZER QUE NÃO FALAMOS DE FLORES ou RASTROS DO SEM-NOME QUE O DIGA é um dos ENSAIOS CAPIROTOS que constituem o VOLUME II do TOMO VIII “DO EXPERIENCIAR”, do MANUAL TEÓRICO-PRÁTICO DE ARTES DRÁSTICAS. -

Contemporary Perspectives on Natural Law

1 CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVES ON NATURAL LAW 2 [Dedication/series information/blank page] 3 CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVES ON NATURAL LAW NATURAL LAW AS A LIMITING CONCEPT 4 [Copyright information supplied by Ashgate] 5 CONTENTS Note on the sources and key to abbreviations and translations Introduction Part One The Concept of Natural Law 1. Ana Marta González. Natural Law as a Limiting Concept. A Reading of Thomas Aquinas Part Two Historical Studies 2. Russell Hittinger. Natural Law and the Human City 3. Juan Cruz. The Formal Foundation of Natural Law in the Golden Age. Vázquez and Suárez’s case 4. Knud Haakonssen. Natural Law without Metaphysics. A Protestant Tradition 5. Jeffrey Edwards. Natural Law and Obligation in Hutcheson and Kant 6. María Jesús Soto–Bruna. Spontaneity and the Law of Nature. Leibniz and the Precritical Kant 7. Alejandro Vigo. Kant’s Conception of Natural Right 8. Montserrat Herrero. The Right of Freedom Regarding Nature in G. W. F. Hegel’s Philosophy of Right 6 Part Three Controversial Issues about Natural Law 9. Alfredo Cruz. Natural Law and Practical Philosophy. The Presence of a Theological Concept in Moral Knowledge 10. Alejandro Llano. First Principles and Practical Philosophy 11. Christopher Martin. The Relativity of Goodness: a Prolegomenon to a Rapprochement between Virtue Ethics and Natural Law Theory 12. Urbano Ferrer. Does the Naturalistic Fallacy Reach Natural Law? 13. Carmelo Vigna. Human Universality and Natural Law Part Four Natural Law and Science 14. Richard Hassing. Difficulties for Natural Law Based on Modern Conceptions of Nature 15. John Deely. Evolution, Semiosis, and Ethics: Rethinking the Context of Natural Law 16. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Ideas y Valores ISSN: 0120-0062 Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Departamento de Filosofía. Valenzuela-Vermehren, Luis Creating Justice in an emerging world the natural Law basis of francisco de vitoria's political and international thought Ideas y Valores, vol. LXVI, no. 163, 2017, January-April, pp. 39-64 Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Departamento de Filosofía. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/ideasyvalores.v66n163.49770 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=80955008002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/ideasyvalores.v66n163.49770 Creating Justice in an Emerging World The Natural Law Basis of Francisco de Vitoria’s Political and International Thought • La creación de la justicia en un mundo naciente El fundamento iusnaturalista del pensamiento político e internacional de Francisco de Vitoria Luis Valenzuela-Vermehren* Universidad Católica de Temuco - Temuco - Chile Artículo recibido el 19 de febrero del 2015; aprobado el 20 de abril del 2016. * [email protected] Cómo citar este artículo: mla: Valenzuela-Vermehren, L. “Creating Justice in an Emerging World. The Natural Law Basis of Francisco de Vitoria’s Political and International Thought.” Ideas y Valores 66.163 (2017): 39-64. apa: Valenzuela-Vermehren, L. (2017). Creating Justice in an Emerging World. The Natural Law Basis of Francisco de Vitoria’s Political and International Thought.Ideas y Valores, 66 (163), 39-64. -

Wilderness and Human Communities

Wilderness and Human Communities s Proceedings from the / TTlr smms UNLNERNESS coNGXASS trt lllt *rrf* P ort Elizabeth. South Africa Edited by Vance G. Martin and Andrew Muir A Fulcrum Publishing Golden, Colorado Copyright @ 2004 The International'Wilderness Leadership (\7ILD) Foundadon Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data \(orld'l7ilderness Congress (7th : 2007 : Port Elizabeth, South Africa) 'Wilderness and human communities : the spirit of the 21st century: proceedings from the 7th \7orld \Tilderness Congress, Port Elizabeth, South Africa I edited by Vance G. Martin and Andrew Muir. P.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55591-855-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. \Tilderness areas-Alrica- Congresses. 2.'\Tilderness areas-Congresses. 3. Nature conservation- Citizen participation-Congresses. I. Martin, Vance. II. Muir, Andrew. III. Title. QH77.435W67 2001 333.78'2r6-d22 2004017590 Printed in the United States of America 098755432r A Fulcrum Publishing The \7ILD Foundation 16100 Thble Mountain Parkway, Suite 300 P O. Box 1380 Golden, Colorado, USA 80403 Ojai, California,USA93023 (800) 992-2908 . (303) 277-1623 (805) 640-0390 'Fax (805) 640-0230 www.fulcrum-boolc.com [email protected] ' www.wild.org *1, .1q1r:a411- t rrr.,rrtr.qgn* Table of Contents vii The Port Elizabeth Accord of the 7rh Vorld Vilderness Congress ix Foreword The 7th \Vorld\Vildemess Congres Renms tu lts Roots in,4frica Andrew Muir xi Introduction \Vild Nature-A Positiue Force Vance G. Martin xiii Acknowledgmenm xv Editort Notes rviii Invocation-A Plea for Africa Baba Credo Mutwa IN Houon. oF IAN Pr-AyeR, FownEn oF THE .l7rrorRNpss \7op.r"o CoNcnrss 3 Umadoh-A Great Son of South Africa The Honorable Mangosuthu Buthelezi, MP 7 \ilTilderness-The Spirit of the 21st Century Ian Player PrRsprcrwrs eNo Rrponts pnou ARotxn tnn t07oRtt 17 The Global Environment Faciliryt Commitment to 'Wilderness Areas Mohamed T.