PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

En Letterkunde. Aanwinsten Van Anet

Taal- en letterkunde. Aanwinsten van SBA: 701618 Anet — Periode 2006/09 La correspondance commerciale franc¸aise / Liliane Bas ; Catherine Hesnard. — Paris : Nathan, 2005. — 159 p. — Semiotiek (Reperes` pratiques ; 26). — ISBN-10 2–09–183187–5 PLANTIJN–MEI: OK–Fra 837 REPE Face to face: portraits of the divine in early Christianity / Robin Margaret Jensen. — Minneapolis, Minn. : Fortress Press, Totemtaal / Martien Berben ; Ine Callebaut ; Marleen Colpin ; 2004. — 234 p., ill. — ISBN-10 0–8006–3678–3 ; e.a. — Mechelen : Wolters Plantyn, 2006. — 5 v. — Met ISBN-10 0–8006–6092–7 Werkboek; Spellingboek; Inleiding en evaluatie; UA–CST: RG 2138 D 44 Themahandleidingen en kopieerbladen; Audio-CD HA–BLS: HA–BLS 372.880.39 SO–TOTE 2006 Key terms semiotics / Bronwen Martin ; Felizitas Ringham. — Tekstboek 2A; Spellingboek 2; Werkboek 2A; Inleiding en London : Continuum, 2006. — 275 p. — evaluatie 2; Themahandleidingen en kopieerbladen 2 ISBN-10 0–8264–8456–5 HL–CH: 475.2 TOTE 2006 UHasselt: 800 MART 2006 HA–BLSL: HA–BLSL 372.880.39 G–TOTE 2006 Tekstboek 2A; Spellingboek 2; Werkboek 2A; Inleiding en Symbolen constructies: 597 universele symbolen / Inez evaluatie 2; Themahandleidingen en kopieerbladen 2A Michiels. — Leuven : Acco, 2006. — 176 p. — ISBN-10 90–334–5919–1 Speculum: de Romeinen in hun geschriften, Latijns leerboek KdG–SAW: 805.5 voor M.O. en N.O. / Jozef Bergmans ; F. Stacino. — 2 ed. — Antwerpen : Sikkel, 1967. — 426 p. Symboliek in de samenleving: een sociologie van de symbolen SBA: 701493 en van het symboliek denken / J.A. Ponsioen ; [medew.] P.J. Bouman. — Utrecht : Bijleveld, 1952. — 271 p. Driemaal taal / Marianne Bodde-Alderlieste ; Harry Paus ; UA–CST: UIA–B 10704 e.a. -

Conflict in the House of Refuge by Willem Frederik Hermans Emilia

153 “The war does not exist” (Inner) Conflict inThe House of Refuge by Willem Frederik Hermans Emilia de Feyter Received: 15.02.2018 – Accepted: 18.04.2018 Título / Titre / Titolo q “La guerra no existe”. Conflicto (interior) enThe House of Refuge de Willem Frederik Quand le narrateur de Willem Frederik Hermans découvre La Maison du Refuge, il Hermans dit: “La guerre n’existe pas (Hermans, 1952, 7)”. L’analyse suivante démontre que “La guerre n’existe pas”. Conflit (intérieur) dans The House of Refuge de Willem dans La Maison du Refuge, le conflit existe à plusieurs niveaux interdépendants. D’une Frederik Hermans part, il y a le conflit extérieur de la guerre, qui est inévitable et qui détruit la notion “La guerra non esiste”. Conflitto (interno) The House of Refuge di Willem Frederik illusionniste de l’ordre. Cette illusion d’ordre pourrait être représentée comme une Hermans utopie. De plus, il y a des oppositions spatiales, en conflit les unes avec les autres: la nature contre la culture et la sécheresse contre l’eau. D’autre part, le conflit intérieur dérange l’esprit du narrateur peu fiable, qui lutte avec le conflit psychologique de la pulsion de mort et qui a des pensées existentialistes et absurdes, qui s’isole de la Abstract / Resumen / Résumé / Riassunto société, qui essaie de changer son identité et qui nie que le la guerre existe. Cette en- quête sur le conflit contribue à la compréhension de ce que les soldats ont traversé When the narrator of Willem Frederik Hermans’ novella discovers The House of pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. -

Week 1 – WILLEM FREDERIK HERMANS, Zijn Leven En Werk Schrijver, Polemist, Enfant Terrible, Één Van De Grote Drie

Week 1 – WILLEM FREDERIK HERMANS, zijn leven en werk Schrijver, polemist, enfant terrible, één van De Grote Drie. Van 5-11 november staat Willem Frederik Hermans centraal. Wat weten we nog niet van hem? Wie was hij werkelijk? Wat waren zijn drijfveren? Wat maakte hem zo geniaal? Boeken – fictie Hermans, Willem Frederik - Au pair Pauline, een 19-jarige studente Frans en kunstgeschiedenis gaat als au pair naar Parijs waar zij eerst terecht komt bij een bizar advocatengezin en later wordt opgenomen door de kunstminnende familie van een steenrijke generaal. Hermans, Willem Frederik - Het behouden huis Een partizaan houdt zich in de Tweede Wereldoorlog schuil in een schijnbaar verlaten huis. Hermans, Willem Frederik - Conserve In de Amerikaanse mormonenstad Salt Lake City ontstaan religieuze en erotische complicaties in de relatie tussen twee dochters van een rijke mormoon en hun halfbroer. Hermans, Willem Frederik - Drie melodrama's : Conserve, De leproos van Molokaï, Hermans is hier geweest Hermans, Willem Frederik - Het evangelie van O. Dapper Dapper : een vervolg op De god denkbaar denkbaar de god Vanwege een biljartbal in zijn mond en een buitenmaatse duim stuit een schrijver op uiteenlopende problemen Hermans, Willem Frederik - De geur van een pasgestoomde deken : de beste poezenstukken Keuze van teksten over eigen en andermans poezen uit het werk van Hermans. Hermans, Willem Frederik - De god denkbaar, denkbaar de god Speels-experimenteel relaas van de zoektocht van een god naar zijn goddelijkheid. Hermans, Willem Frederik - Een heilige van de horlogerie De zoon van een naar Frankrijk geëmigreerde Nederlandse boer en een Franse vrouw komt na zijn studie filosofie niet aan de slag en verdient daarom de kost als klokkenopwinder in een leegstaand paleis. -

Tilburg University De Ernst Van Het Spel Rutten, Daan

Tilburg University De ernst van het spel Rutten, Daan Publication date: 2016 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Rutten, D. (2016). De ernst van het spel: Willem Frederik Hermans en de ethiek van de persoonlijke mythologie. Verloren. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. sep. 2021 De ernst van het spel Opgedragen aan Ger Rutten-Lentjes (1923-2010) en Adriana Goevaers-Zwaan (1922-2015), grootmoeders van de autonomie en de fantasie. Deze uitgave is mede tot stand gekomen dankzij de financiële steun van Stichting Jaap Harten Fonds, de J.E. Jurriaanse Stichting, Stichting dr. Hendrik Muller’s Vaderlandsch Fonds, Stichting Professor Van Winter Fonds en het Instituut voor Cultuurwetenschappelijk Onderzoek (icon) van de Universiteit Utrecht. Afbeelding op het omslag: portret van Willem Frederik Hermans uit 1951 door Emiel van Moerkerken. -

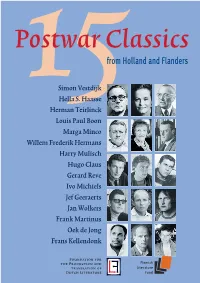

From Holland and Flanders

Postwar Classics from Holland and Flanders Simon Vestdijk 15Hella S. Haasse Herman Teirlinck Louis Paul Boon Marga Minco Willem Frederik Hermans Harry Mulisch Hugo Claus Gerard Reve Ivo Michiels Jef Geeraerts Jan Wolkers Frank Martinus Oek de Jong Frans Kellendonk Foundation for the Production and Translation of Dutch Literature 2 Tragedy of errors Simon Vestdijk Ivory Watchmen n Ivory Watchmen Simon Vestdijk chronicles the down- I2fall of a gifted secondary school student called Philip Corvage. The boy6–6who lives with an uncle who bullies and humiliates him6–6is popular among his teachers and fellow photo Collection Letterkundig Museum students, writes poems which show true promise, and delights in delivering fantastic monologues sprinkled with Simon Vestdijk (1898-1971) is regarded as one of the greatest Latin quotations. Dutch writers of the twentieth century. He attended But this ill-starred prodigy has a defect: the inside of his medical school but in 1932 he gave up medicine in favour of mouth is a disaster area, consisting of stumps of teeth and literature, going on to produce no fewer than 52 novels, as the jagged remains of molars, separated by gaps. In the end, well as poetry, essays on music and literature, and several this leads to the boy’s downfall, which is recounted almost works on philosophy. He is remembered mainly for his casually. It starts with a new teacher’s reference to a ‘mouth psychological, autobiographical and historical novels, a full of tombstones’ and ends with his drowning when the number of which6–6Terug tot Ina Damman (‘Back to Ina jealous husband of his uncle’s housekeeper pushes him into Damman’, 1934), De koperen tuin (The Garden where the a canal. -

Book Adaptation Rights Market 01 – 03.09.2017

BOOK ADAPTATION RIGHTS MARKET 01 – 03.09.2017 www.labiennale.org BOOK ADAPTATION RIGHTS MARKET 74. Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica La Biennale di Venezia Venice Book Adaptation The collaborators Director General Rights Market for the Book Adaptation Andrea Del Mercato Rights Market Consultant Erika Giorgianni Artistic Director of the Virginie Franz Elena Mantoan Cinema Department Chiara Marin Alberto Barbera Sara Mazzucchi Alessandro Mezzalira Head of the Nikolas Montaldi Cinema Department The team is pleased to present the 2nd edition of the Luigi Cuciniello Venice Production Bridge Book Adaptation Rights Market which will take place within the context of the 74th Venice International Film Festival. Venice Production Bridge Pascal Diot We never know whether a new concept would deal with people’s demands and thus we were Savina Neirotti more than happy when, after the first edition of last year, we received the publishers’ feedbacks. [email protected] www.labiennale.org It was the first time for them that, rather than focusing on one book, they were able to present their entire catalogues and, above all, they had the time to have in-depth conversations with the producers. Fostering long term relationship between them was our aim and we achieved it. Consequently, we decided to increase the number of publishers to 19 and to expand it beyond the European borders. This year, publishers from USA and Japan have joined our French, Spanish, Italian, Greek, Dutch, Belgian, English and German established publishing companies. We thank all those publishers who are presenting an incredibly wide range of novels, drama, children’s literature, genre fiction, short stories, comics, mangas, graphic novels, essays… suitable for cinema and audiovisual adaptations. -

Weg Met De Revolutie!

WEG MET DE REVOLUTIE! WF HERMANS ALLE VERHALEN I.indd 1 22-05-19 17:22 LITERAIRE BIBLIOTHEEK Deel 1 Gerard Reve, De duiding aller dingen. Gerard Reve in Elsevier. Elsevier over Gerard Reve (2007) Deel 2 Godfried Bomans, Genieten in een gekkenhuis. De beste stukken uit Elsevier (2011) Deel 3 Cees Nooteboom, Op reis. Alle verhalen uit Elsevier. Deel 1: 1957-1960 (2012) Deel 4 Cees Nooteboom, Op reis. Alle verhalen uit Elsevier. Deel 2: 1986-2007 (2013) Deel 5 André Malraux, Gevelde eiken. Gesprekken met Charles de Gaulle (2014) Deel 6 W.F. Hermans, Weg met de revolutie! Al zijn artikelen uit Elsevier Weekblad (2019) WF HERMANS ALLE VERHALEN I.indd 2 22-05-19 17:22 W.F. Hermans Weg met de revolutie! AL ZIJN ARTIKELEN UIT ELSEVIER WEEKBLAD WF HERMANS ALLE VERHALEN I.indd 3 22-05-19 17:22 Eerste druk: mei 2019 © Erven Willem Frederik Hermans © Uitgeverij EW Redactie: Marijke Brouwer en Tonny van Winssen Omslagontwerp: Peter ter Mors Boekverzorging: jooZt Mattheij Foto omslag: Freddy Rikken Druk en bindwerk: Wilco, Amersfoort Uitgeverij EW, Postbus 11, 1110 AA Diemen Bestellen: shop.elsevierweekblad.nl ISBN: 978 94 634 8064 2 NUR: 622 Elsevier is een geregistreerd merk van Elsevier B.V. en wordt gebruikt onder licentie. WF HERMANS ALLE VERHALEN I.indd 4 23-05-19 17:04 INHOUD Inleiding – Gerry van der List 9 In gesprek met mijzelf 29 De zitting 33 Tien herdersuurtjes 44 De verwaarloosde schrijver 50 Schichtig en nog luier 51 Een volk van knopjesdrukkers 60 Van duisternis tot licht, en terug 70 Het laatste woord over King Kong? 80 De jonge en -

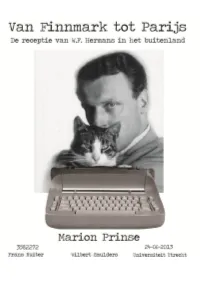

Bachelorscriptie3582272.Pdf

1.Inleiding “’’t Lot van de vertaler is niet te benijden”, zo schreef Hermans in 1980 in Magiërs en Vertalers.Hij schreef dit naar aanleiding van de vertaling ‘een kalkoentje champagne’, die de gerennomeerde vertaler John Vandenbergh van het Engelse ‘a snipe of champagne’ maakte. Een vondst waarvan Hermans onder de indruk was ‘want, groot liefhebber van de prikdrank in kwestie, kon ik niet begrijpen waarom de term “kalkoentje” mij totaal onbekend was. Ik heb het opgezocht in Van Dale. Het blijkt een flesje met een inhoud van 0,2 liter te zijn. Nou goed. Ik drink champagne nooit uit zulke kleine flesjes als Vandenbergh klaarblijkelijk. ’t Lot van de vertaler is niet te benijden.’ (Hermans aangehaald door Cunin) Cunin is de Franse vertaler van De donkere kamer van Damokles (La Chambre noire de Damoclès, 2006) en Nooit meer slapen (Ne plus jamais dormir, 2009). Cunin vertelt dat hij één keer op champagne is getrakteerd door zijn uitgeverij, namelijk na verschijning van de recensie van Milan Kundera over La Chambre noire de Damoclès in Le Monde. Opvallend is dat Hermans’ succes in het buitenland pas deze eeuw echt op gang is gekomen. In de Verenigde Staten werd The Darkroom of Damocles genomineerd voor het best vertaalde boek van 2008 (Leyman) en in Duitsland stond Die Dunkelkammer des Damokles in 2001 in de bestseller top 10. Ook de vertalingen van Nooit meer slapen konden rekenen op veel belangstelling. Hoe kan het dat Hermans nu ineens zoveel succes geniet in het buitenland? Waarom zijn eerdere vertalingen niet succesvol geworden? Komt het door de kwaliteit van de vertalingen, het gebrek aan belangstelling voor Nederlandse literatuur of wellicht door de eerdere bemoeienis van Hermans zelf? Hoe is de receptie van zijn werk precies verlopen? Dit zijn vragen die in mij opkwamen toen ik hoorde van deze opvallende ontwikkeling. -

(Inner) Conflict in the House of Refuge by Willem Frederik Hermans

Article “The War does not Exist”. (Inner) Conflict in The House of Refuge by Willem Frederik Hermans DE FEYTER, Emilia Reference DE FEYTER, Emilia. “The War does not Exist”. (Inner) Conflict in The House of Refuge by Willem Frederik Hermans. EU-topias, 2018, vol. 15, p. 153-161 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:133715 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 153 “The War does not Exist” (Inner) Conflict inThe House of Refuge by Willem Frederik Hermans Emilia de Feyter Received: 15.02.2018 – Accepted: 18.04.2018 Título / Titre / Titolo Quand le narrateur de Willem Frederik Hermans découvre La Maison du Refuge, il “La guerra no existe”. Conflicto (interior) enThe House of Refuge de Willem Frederik dit: “La guerre n’existe pas (Hermans, 1952, 7)”. L’analyse suivante démontre que Hermans dans La Maison du Refuge, le conflit existe à plusieurs niveaux interdépendants. D’une “La guerre n’existe pas”. Conflit (intérieur) dans The House of Refuge de Willem part, il y a le conflit extérieur de la guerre, qui est inévitable et qui détruit la notion Frederik Hermans illusionniste de l’ordre. Cette illusion d’ordre pourrait être représentée comme une “La guerra non esiste”. Conflitto (interno) inThe House of Refuge di Willem Frederik utopie. De plus, il y a des oppositions spatiales, en conflit les unes avec les autres: la Hermans nature contre la culture et la sécheresse contre l’eau. D’autre part, le conflit intérieur dérange l’esprit du narrateur peu fiable, qui lutte avec le conflit psychologique de la pulsion de mort et qui a des pensées existentialistes et absurdes, qui s’isole de la société, qui essaie de changer son identité et qui nie que le la guerre existe. -

The Aggressive Logic of Singularity: Willem Frederik Hermans1 Frans Ruiter, University of Utrecht, and Wilbert Smulders, University of Utrecht

The Aggressive Logic of Singularity: Willem Frederik Hermans1 Frans Ruiter, University of Utrecht, and Wilbert Smulders, University of Utrecht Abstract: Willem Frederik Hermans is considered to be one of the major Dutch authors of the twentieth century. In his novels ideals of every kind are unmasked, and his Weltanschauung leaves little room for pursuing a ‘good life’. Nevertheless, there seems to be one option left to him, namely literature. In his poetic essays he explains that literature has nothing to do with escapism, but offers a vital way of facing the bleak facts of life. Literary critics and scholars have commented extensively on his poetic ideas, but have never truly addressed the riddle Hermans’ œuvre confronts us with: what might be the value of writing in a world without values? In this article we will focus on this paradoxical problem, which could perhaps be characterized as one of ‘aesthetics of nihilism’. We argue that Hermans’ so-called autonomous and a-political literary position can certainly be interpreted as a form of commitment that goes far beyond literature. We will first give an overview of Hermans’ work. Subsequently we will reflect on the social and cultural status of literary autonomy. Our main aim is to analyze a critical text by Hermans which seems clear at first sight but actually is rather enigmatic: the compact, well- known essay Antipathieke romanpersonages (‘Unsympathetic Fictional Characters’).2 Keywords: Literary Autonomy, Alterity, Willem Frederik Hermans Singularity: to Spring a Leak in the Fullness… In his autobiographical story Het grote medelijden (The Great Compassion) Hermans’ alter ego Richard Simmilion says about the people who surround him, i.e. -

Fokas Holthuis

antiquariaat FOKAS HOLTHUIS DE SCHOONE JACHT catalogus 50 literatuur ∙ brieven ∙ varia with a section in english antiquariaat FOKAS HOLTHUIS Fokas Holthuis Paul Snijders Nick ter Wal Postbus 18604 NL – 2502 EP Den Haag telefoon 070 – 346 6020 www.fokas.nl [email protected] www.paulbooks.nl [email protected] KvK Haaglanden 10041294 BTW NL 8103.27.910.B01 Illustratie voorzijde: nummer 153 in deze catalogus. Illustratie achterzijde: nummer 97 in deze catalogus. LEVERINGSVOORWAARDEN * Prijzen zijn in euro’s * Verzendkosten zijn voor rekening van de koper * Betaling binnen 14 dagen op één van onze rekeningen * Wij behouden ons het recht voor pas te leveren na betaling Wij versturen wekelijks een nieuwsbrief met aanwinsten of lijstjes rondom een thema of auteur per e-mail. Abonneert u zich (gratis) onder ‘Nieuwsbrieven’ op onze website. 1-132 Nederlandse literatuur in handschriften, foto’s & bijzondere uitgaven 133-151 Eenmanstijdschriften & zeldzame periodieken 152-162 H.N. Werkman 163-170 De Zilverdistel 171-178 Kunera Pers 179-220 Mooi, mal of meesterlijk: boeken, handschriften & efemeer drukwerk 221-263 Treasures and curiosities: books, autographs & ephemera oktober 2010 1 AAFJES, Bertus Handgeschreven brief aan 'Beste Rein [Blijstra]'. 25,4 x 19,2 cm. Gelinieerd blocnotevel. Eén blad. Alleen recto. Gesigneerd 'Bertus Aafjes' en gedateerd 'Den Haag 4 Febr. 46'. 14 regels tekst. Plakbandresten aan bovenzijde (niet storend). € 25 * De schrijver wil zich bij redacteur Blijstra graag abonneren op Critisch Bulletin: 'Ik vind dat 1e nr. het lezenswaardigste wat er tot nu toe aan tijdschrift-nrs verscheen. Het abonnementsgeld laat zich dan wel verrekenen met het honorarium voor de bijdragen'. -

Schrijven Is Verbluffen Bibliografie Van De Verspreide Publicaties Van Willem Frederik Hermans

Schrijven is verbluffen Bibliografie van de verspreide publicaties van Willem Frederik Hermans Rob Delvigne en Frans A. Janssen bron Rob Delvigne en Frans A. Janssen, Schrijven is verbluffen. Bibliografie van de verspreide publicaties van Willem Frederik Hermans. Thomas Rap, Amsterdam 1996 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/jans037schr01_01/colofon.php © 2005 dbnl / Rob Delvigne & Frans A. Janssen i.s.m. 2 Schrijven is verbluffen Bibliografie van de verspreide publicaties van Willem Frederik Hermans 7 De Hollerithkaart (woord vooraf bij de eerste druk, 1972) 1 Dit boekje behelst een lijst van wat ik ooit heb bijgedragen aan kranten, tijdschriften en zo meer: verspreide publicaties. De samenstellers hopen dat hun opsomming van titels volledig is tot en met augustus 1972. Ik zou onwaarheid spreken als ik beweerde dat de vrucht van hun ijver mij bijzonder vrolijk gestemd heeft. Maar dit is mijn eigen schuld en niet de hunne. Had ik maar nooit in mijn leven iets opgeschreven dat ik later niet meer belangrijk zou vinden. Had ik maar altijd precies gezegd wat ik bedoelde! Deze catalogus ontrukt zelfs het alleronbeduidendste aan de vergetelheid. Doornroosjes die nooit meer wakker hadden moeten worden, krijgen de kans haar ogen op te slaan en wie weet wat welke aanbidders zullen menen daarin te kunnen lezen. Ik word doodmoe bij de gedachte dat deze of gene schriftgeleerde gewichtige maar foute exegeses zal weten te distilleren uit een terecht compleet vergeten verhaaltje, waarvan hij de titel en de plaats waar het afgedrukt staat gevonden heeft in deze bibliografie. Want dat is het, waarvoor de wijsneuzen haar zullen gebruiken: om het beter te weten dan ik.