FINAL-AMICUS-BRIEF.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

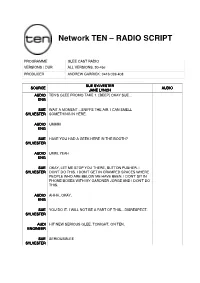

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT PROGRAMME GLEE CAST RADIO VERSIONS / DUR ALL VERSIONS. 30-45s PRODUCER ANDREW GARRICK: 0416 026 408 SUE SYLVESTER SOURCE AUDIO JANE LYNCH AUDIO TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] OKAY SUE… ENG SUE WAIT A MOMENT…SNIFFS THE AIR. I CAN SMELL SYLVESTER SOMETHING IN HERE. AUDIO UMMM ENG SUE HAVE YOU HAD A GEEK HERE IN THE BOOTH? SYLVESTER AUDIO UMM, YEAH ENG SUE OKAY, LET ME STOP YOU THERE, BUTTON PUSHER. I SYLVESTER DON'T DO THIS. I DON'T GET IN CRAMPED SPACES WHERE PEOPLE WHO ARE BELOW ME HAVE BEEN. I DON'T SIT IN PHONE BOXES WITH MY GARDNER JORGE AND I DON'T DO THIS. AUDIO AHHH..OKAY. ENG SUE YOU DO IT. I WILL NOT BE A PART OF THIS…DISRESPECT. SYLVESTER AUDI HIT NEW SERIOUS GLEE. TONIGHT, ON TEN. ENGINEER SUE SERIOUSGLEE SYLVESTER Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT FINN HUDSON SOURCE AUDIO CORY MONTEITH FEMALE TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. THANKS. HI AUSTRALIA, IT'S FINN HUSON HERE, HUDSON FROM TEN'S NEW SHOW GLEE. FEMALE IT'S REALLY GREAT, AND I CAN ONLY TELL YOU THAT IT'S FINN COOL TO BE A GLEEK. I'M A GLEEK, YOU SHOULD BE TOO. HUDSON FEMALE OKAY, THAT'S PRETTY GOOD FINN. CAN YOU MAYBE DO IT AUDIO WITH YOUR SHIRT OFF? ENG FINN WHAT? HUDSON FEMALE NOTHING. AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY… HUDSON FEMALE MAYBE JUST THE LAST LINE AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. UMM. GLEE – 730 TONIGHT, ON TEN. SERIOUSGLEE HUDSON FINN OKAY. -

1 Nominations Announced for the 19Th Annual Screen Actors Guild

Nominations Announced for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Ceremony will be Simulcast Live on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2013 on TNT and TBS at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) LOS ANGELES (Dec. 12, 2012) — Nominees for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® for outstanding performances in 2012 in five film and eight primetime television categories as well as the SAG Awards honors for outstanding action performances by film and television stunt ensembles were announced this morning in Los Angeles at the Pacific Design Center’s SilverScreen Theater in West Hollywood. SAG-AFTRA Executive Vice President Ned Vaughn introduced Busy Philipps (TBS’ “Cougar Town” and the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® Social Media Ambassador) and Taye Diggs (“Private Practice”) who announced the nominees for this year’s Actors®. SAG Awards® Committee Vice Chair Daryl Anderson and Committee Member Woody Schultz announced the stunt ensemble nominees. The 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® will be simulcast live nationally on TNT and TBS on Sunday, Jan. 27 at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) from the Los Angeles Shrine Exposition Center. An encore performance will air immediately following on TNT at 10 p.m. (ET)/7 p.m. (PT). Recipients of the stunt ensemble honors will be announced from the SAG Awards® red carpet during the tntdrama.com and tbs.com live pre-show webcasts, which begin at 6 p.m. (ET)/3 p.m. (PT). Of the top industry accolades presented to performers, only the Screen Actors Guild Awards® are selected solely by actors’ peers in SAG-AFTRA. -

Sexting Gone Wild: Who’S Doing It and Why for Me

Ohr Chadash 14 Ohr Chadash 15 14A | SEPTEMBER 8, 2010 | ST. LOUIS JEWISH LIGHT | Visit WWW. STLJEWISHLIGHT.COM Visit WWW. STLJEWISHLIGHT.COM | ST. LOUIS JEWISH LIGHT | SEPTEMBER 8, 2010 | 15A Sexting gone wild: who’s doing it and why for me. Take a dirty picture,” sing Taio Cruz and Katie, who attends Lafayette High School. ed on the Internet or passed around among BY AKRITI PANTHI Ke$ha in their hit song, “Picture.” Researchers have formed their own conclu- peers. The prevalence of sexting in the modern sions about this new trend. According to www. “Sexting is inappropriate because you never world could contribute to its rodale.com, Debby know what the other person could do with your any teens continue to feel pressured to appeal, but some teens see Herbenick, associate picture. Most of my friends send sexts to people try drinking, drugs, and sex, but recently M other motivations to sext. director of the Center that they do not know that well,” said Joe, 16, a new trend has been in fashion: sexting. “I think most people are curi- for Sexual Health who goes to Parkway Central High. The majority of us are familiar with alcohol, ous about what sexting really is. Promotion at Indiana According to www.wiredsaftey.org, expert drugs, and sex, but what exactly is sexting? I know I was when I began State University, said, Parry Aftab, a lawyer who specializes in Internet “Sexting is all about getting the nude pictures. doing it. My friends would “Sexting can be a form and privacy issues claims on ABC News, said, Without the pictures it is just dirty talk, and always say that they felt really of identity exploration “44 percent of the high school boys that we those pictures surely stimulate more senses,” dirty doing it, but it was enjoy- and expression. -

Cast Members from FOX's New Musical Comedy Series GLEE to Ring the NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell

Cast Members From FOX's New Musical Comedy Series GLEE to Ring The NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell ADVISORY, Sep 29, 2009 (GlobeNewswire via COMTEX News Network) -- What: Cory Monteith and Amber Riley from FOX's new musical comedy series, GLEE, will preside over the NASDAQ Closing Bell to celebrate the show's first season pick-up. GLEE airs on Wednesday's at 9:00-10:00 PM ET/PT on FOX. Where: NASDAQ MarketSite - 4 Times Square - 43rd & Broadway - Broadcast Studio When: Wednesday, September 30th 2009 at 3:45 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. ET Contacts: Elissa Johansmeier Vice President, Publicity & Corporate Communications Fox Broadcasting Company phone: 212-556-2567 email: [email protected] NASDAQ MarketSite: Jolene Libretto (646) 441-5220 [email protected] Feed Information: The Closing Bell is available from 3:50 p.m. to 4:05 p.m. on AMC-3/C-3 (ul 5985V; dl 3760H). The feed can also be found on Ascent fiber 1623. If you have any questions, please contact Jolene Libretto at (646) 441-5220. Radio Feed: An audio transmission of the Closing Bell is also available from 3:50 p.m. to 4:05 p.m. on uplink IA6 C band / transponder 24, downlink frequency 4180 horizontal. The feed can be found on Ascent fiber 1623 as well. Webcast: A live webcast of the NASDAQ Closing Bell will be available at: http://www.nasdaq.com/about/marketsitetowervideo.asx Photos: To obtain a high-resolution photograph of the Market Close, please go to http://www.nasdaq.com/reference/marketsite_events.stm and click on the market close of your choice. -

CINE MEJOR ACTOR JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake

CINE MEJOR ACTOR JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) MEJOR ACTRIZ SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) MEJOR ACTOR DE REPARTO MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey - "THE LOVELY BONES" (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa - "INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS" (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MEJOR ACTRIZ DE REPARTO PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark - "INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS" (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MEJOR ELENCO AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. J.T. -

Glee, Flash Mobs, and the Creation of Heightened Realities

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction University Libraries Publications and Scholarship University Libraries 9-20-2016 Glee, Flash Mobs, and the Creation of Heightened Realities Elizabeth Downey Mississippi State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/ul-publications Recommended Citation Downey, Elizabeth M. "Glee, Flash Mobs, and the Creation of Heightened Realities." Journal of Popular Film & Television, vol. 44, no. 3, Jul-Sep2016, pp. 128-138. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/ 01956051.2016.1142419. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Libraries Publications and Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Glee and Flash Mobs 1 Glee, Flash Mobs, and the Creation of Heightened Realities In May of 2009 the television series Glee (Fox, 2009-2015) made its debut on the Fox network, in the coveted post-American Idol (2002-present) timeslot. Glee was already facing an uphill battle due to its musical theatre genre; the few attempts at a musical television series in the medium’s history, Cop Rock (ABC, 1990) and Viva Laughlin (CBS, 2007) among them, had been overall failures. Yet Glee managed to defeat the odds, earning high ratings in its first two seasons and lasting a total of six. Critics early on attributed Glee’s success to the popularity of the Disney Channel’s television movie High School Musical (2006) and its subsequent sequels, concerts and soundtracks. That alone cannot account for the long-term sensation that Glee became, when one acknowledges that High School Musical was a stand-alone movie (sequels notwithstanding). -

Glee’ Contributed by Benjy Maor Source: by Jay Michaelson from the Jewish Daily Forward

CHILDREN The Four ‘Sons’ as Characters From ‘Glee’ Contributed by Benjy Maor Source: By Jay Michaelson from the Jewish Daily Forward As it happens, the four Jewish characters in McKinley High School’s glee club map quite neatly onto the four children of the Passover Seder, and the way each of them performs his or her Jewishness shines a different light on American Jewish identity, and on the themes of the Passover holiday. Rachel Berry (Lea Michele) is the “Wise Child” — to a fault. She endlessly touts her Jewishness in one way or another, from Barbra Streisand songs to protests at Christmastime. She is also an irritating control freak, just like the unctuous Wise Child, who asks annoying, detailed questions about the statutes, laws and ordinances that God has commanded. The Haggadah obviously wants us to praise this kid, but most years I just want to slap him. Just like Rachel, he’s a know-it-all and a drama queen. “Look at me!” the Wise Child brags, just as Rachel does. Look how smart and good I am! Like Rachel in her goody-two-shoes sweaters, the Wise Child is intolerable. Rachel is a quintessential Jewish stereotype — smart, Semitic-looking, Magen-David-wearing — and yet she performs her Jewishness in the same way she performs her many solos on the show: in your face, turned up to 11. The Wise Child is the same way. Noah “Puck” Puckerman (Mark Salling) is the “Wicked Child.” His is the most original of the Jewishnesses on “Glee,” contradicting every stereotype that Rachel serves to uphold. -

50 Police Officers Arrested in Child Porn Raids | Daily Mail Online

Feedback Like 2.5m Friday, Mar 27th 2015 11PM 45°F 2AM 40°F 5-Day Forecast Home U.K. News Sports U.S. Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Columnists Latest Headlines News Arts Headlines Pictures Most read News Board Wires Login New York hails its Had killer Alps pilot Passengers were Third American Two crew members Why can't airlines 'You only hear the heroes after off-duty just been dumped? doomed by post victim in in the cockpit at seize control of screams in the final 50 police officers arrested in Site Web Enter your search child porn raids open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com child porn raids Fifty police officers across the UK have been arrested as part of a crackdown on suspected paedophiles who pay to access child pornography websites, detectives revealed today. The officers were among 1,300 people arrested on suspicion of accessing or downloading indecent images of children - some as young as five - from US-based Internet sites. Thirty-five men were arrested in London this morning as part of the investigation - codenamed Operation Ore - following raids on 45 addresses across the capital. Of the 50 policemen identified, eight have been charged to date and the remainder bailed pending further inquiries. Scotland Yard said none of those arrested today was a policeman. At a press conference at Scotland Yard today, Jim Gamble, assistant chief constable of the National Crime Squad, said he was not surprised at the number of police officers among the suspects. -

The Glee Cast: Inspiring Gleek Mania (USA Today Lifeline Biographies) Online

7PIW6 [Ebook pdf] The Glee Cast: Inspiring Gleek Mania (USA Today Lifeline Biographies) Online [7PIW6.ebook] The Glee Cast: Inspiring Gleek Mania (USA Today Lifeline Biographies) Pdf Free Felicity Britton audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2810425 in Books 21st Century 2012-08-01Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.60 x .40 x 6.20l, .70 Binding: Library Binding112 pages | File size: 29.Mb Felicity Britton : The Glee Cast: Inspiring Gleek Mania (USA Today Lifeline Biographies) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Glee Cast: Inspiring Gleek Mania (USA Today Lifeline Biographies): 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. This is a fascinating look at the story behind the making of the series of `Glee' and the cast members ...By D. FowlerWilliam McKinley High School's glee club was loaded with a bunch of outcasts. Where else would you find an overweight diva, a "super-talented nerd," a gay loner, a wheelchair-bound boy, and a jock? Throw in a smattering of other losers and what do you come up with? `Glee' of course. If you've ever watched the series, you surely have your favorites among the cast and undoubtedly look forward to seeing them in the next episode. Perhaps all of us can relate to one or another of them as we travel through high school or recall our days there. Co-creator and executive producer, Ryan Murphy, claims that he "wanted to give voices to people who don't have voices."If you've wowed over the glee club's renditions of songs such as Joanne Osborne's "One of Us" or "The Only Exception" by Paramore, you'll definitely want to know about the people behind the voices. -

Hollywood Live Auction's Holiday Extravaganza Live Auction Event

Welcome to Hollywood Live Auction’s Holiday Extravaganza Live Auction event weekend. We have assembled an incredible collection of rare iconic movie props and costumes featuring items from film, television and music icons including John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Christopher Reeve, Michael Jackson, Don Johnson and Kirk Douglas. From John Wayne’s Pittsburgh costume, Michael Jackson’s deed and signed check to The Neverland Ranch, signed Billie Jean lyrics and signed, stage worn Fedora from the HIStory Tour, James Brown’s stage worn jumpsuit, Marilyn Monroe’s gold high heels, Christopher Reeve’s Superman costume, Steve McQueen’s Enemy of the People costume, Robert Redford’s The Natural costume, Kirk Douglas’ Top Secret Affair costume, Johnny Depp’s Blow costume, Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas’ Miami Vice costumes, and many more! Also from the new Immortals starring Mickey Rourke, bring home some of the most detailed costumes and props from the film! If you are new to our live auction events and would like to participate, please register online at HollywoodLiveAuctions.com to watch and bid live. If you would prefer to be a phone bidder and be assisted by one of staff members, please call us to register at (866) 761-7767. We hope you enjoy Hollywood Live Auctions’ Holiday Extravaganza event and we look forward to seeing you on March 24th – 25th for Hollywood Live Auctions’ Auction Extravaganza V. Special thanks to everyone at Premiere Props for their continued dedication in producing these great events. Have fun and enjoy the weekend! Sincerely, Dan Levin Executive VP Marketing Premiere Props 128 Sierra Street El Segundo, CA 90245 Terms & Conditions The following terms and conditions constitute the only terms and conditions under which Premiere Props will offer for sale and sell the property described in the Catalog. -

Table of Contents

table of contents hello, i love you: introduction ix can’t fight this feeling: the origins ofglee 1 this is how we do it: the making of glee 14 you’re the one that i want: principal players matthew morrison (will schuester) 22 lea michele (rachel berry) 24 cory monteith (finn hudson) 26 dianna agron (quinn fabray) 28 jane lynch (sue sylvester) 30 jayma mays (emma pillsbury) 32 amber riley (mercedes jones) 33 chris colfer (kurt hummel) 35 jenna ushkowitz (tina cohen-chang) 37 kevin mchale (artie abrams) 38 mark salling (noah “puck” puckerman) 40 jessalyn gilsig (terri schuester) 41 iqbal theba (principal figgins) 43 patrick gallagher (ken tanaka) 45 heather morris (brittany) 46 naya rivera (santana lopez) 48 harry shum jr. (mike chang) 49 dijon talton (matt rutherford) 51 josh sussman (jacob ben israel) 52 season one: may 2009–june 2010 1.01 “pilot” 53 director’s cut differences 57 the evolution of glee: script differences 62 1.02 “showmance” 65 famous people who were in glee clubs 66 q&a: jennifer aspen as kendra giardi 69 1.03 “acafellas” 73 josh groban 74 01_DSBintro_2.indd 5 7/16/10 2:42:44 PM whit hertford as dakota Stanley 75 victor garber as will’s father 76 debra monk as will’s mother 78 john lloyd young as henri st. pierre 79 1.04 “preggers” 82 mike o’malley as burt hummel 83 q&a: stephen tobolowsky as sandy ryerson 85 1.05 “the rhodes not taken” 91 kristin chenoweth as april rhodes 93 gleek speak: amanda kind 96 1.06 “vitamin d” 99 show choirs versus glee clubs 104 1.07 “throwdown” 104 gleek speak: RPing glee 109 1.08 “mash-up”