The Gissing Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clevedon Court Y7/2010

Clevedon Court Car Park Clevedon Gradiometer survey 2009 YCCCART 2010 / 7 North Somerset HER 47514 YATTON, CONGRESBURY CLAVERHAM AND CLEEVE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH TEAM General editor: Vince Russett Clevedon Court from a 1922 Ward Lock guidebook to Clevedon . Image from Wikimedia Commons 1 Contents 1 Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Site location 5 Land use and geology 6 Historical & archaeological context 7 Survey objectives 8 Methodology 9 Results 10 Recommendations for further work 11 Appendices - Site survey records 2 1. Abstract YCCCART has agreed with the Heritage Lottery Fund to undertake a project over two years commencing May 2009 to a) Establish the extent of the Congresbury Romano British pottery. b) Undertake electronic surveys to establish additional features on Cadbury hill fort, Congresbury and its environs. c) Enable the equipment to be used by Community Archaeology in North Somerset teams to identify new archaeological sites / additional features in North Somerset. This survey provided an excellent learning opportunity for the survey team and also resulted in identification of a potential target site (building?) of interest to Mr David Fogden 2. Acknowledgements A Heritage Lottery Grant enabled the purchase, by YCCCART, of a Bartington Gradiometer 601 without which this survey could not have been undertaken. This survey was carried out at the request of Mr David Fogden, Administrator of the house, and provided YCCCART with a good training opportunity. We are also most grateful to David for providing us with his results and allowing us to publish his drawings. The authors are grateful for the hard work by the members of YCCCART in performing the survey. -

Clevedon Mercury

The Clevedonian Spring 2012 Issue No. 05 PageIn 2 this edition A View from the Chair Group Report - Footpaths Group Page 3 Group Reports Environment Group Local History Group Page 4 Group Report - Conservation Group Page 5 Coming Shortly Page 6 Redeveloping Christchurch Page 7 A Fishy Tale Page 8 Farewell Clevedon Mercury What’s in a Name? Page 9 Doris Hatt - Local Artist Derek Lilly’s Word Search Page 10 & 11 Volunteering for Clevedon Page 12 Clevedon Down Under Page 13 Curzon Centenary Page 14 Clevedon’s Weather Station Society Publications Page 15 Entertainment in Clevedon Page 16 When We Were Very Young Page 17 Branch Line Page 18 Postcard from Clevedon Collector’s Lot Page 19 Military Chest Notice Board Page 20 Members’ Photograph Gallery Artist’s Attic The views expressed are those of the authors, and may or may not represent those of the Society. www.clevedon-civic-society.org.uk/ A VIew from The Chair Report by Hugh Stebbing Environment Group GrouP REporTs Report by Bob Hardcastle (Tel. 871633) elcome to this edition of The those who “make it happen” and ensure We hope that the Bandstand can be WClevedonian. I’m sure that once we don’t just get along by accident. because more civic minded members restored in this current year as this was again you’ll find stories and reports of the public are picking up litter our intended Jubilee project when we of interest. Hopefully, too, you’ll be This edition carries a Notice about the themselves in order to keep their town contacted NSC about the repair work impressed by the range of topics and will Extraordinary General Meeting on 13th In this Diamond Jubilee year we have he Group started its working party looking tidy. -

Download Somerset

Somerset by G.W. Wade and J.H. Wade Somerset by G.W. Wade and J.H. Wade Produced by Dave Morgan, Beth Trapaga and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. [Illustration: A MAP OF THE RAILWAYS OF SOMERSET] [Illustration: THE PINNACLES, CHEDDAR] SOMERSET By G.W. WADE, D.D. and J.H. WADE, M.A. _With Thirty-two Illustrations and Two Maps_ page 1 / 318 "Upon smooth Quantock's airy ridge we roved." London Methuen & Co 36 Essex St. Strand [Illustration: Hand drawn Routes of the Somerset & Dorset Railway] PREFACE The general scheme of this Guide is determined by that of the series of which it forms part. But a number of volumes by different writers are never likely to be quite uniform in character, even though planned on the same lines; and it seems desirable to explain shortly the aim we have had in view in writing our own little book. In our accounts of places of interest we have subordinated the historical to the descriptive element; and whilst we have related pretty fully in the Introduction the events of national importance which have taken place within the county, we have not devoted much space to family histories. We have made it our chief purpose to help our readers to see for themselves what is best worth seeing. If, in carrying out our design, we appear to have treated inadequately many interesting country seats, our excuse must be that such are naturally not very accessible to the ordinary tourist, whose needs we have sought to supply. And if churches and church architecture seem to receive undue attention, it may be page 2 / 318 pleaded that Somerset is particularly rich in ecclesiastical buildings, and affords excellent opportunities for the pursuit of a fascinating study. -

The Historical Journal HENRY HALLAM REVISITED

The Historical Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS Additional services for The Historical Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here HENRY HALLAM REVISITED MICHAEL BENTLEY The Historical Journal / Volume 55 / Issue 02 / June 2012, pp 453 473 DOI: 10.1017/S0018246X1200009X, Published online: 10 May 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X1200009X How to cite this article: MICHAEL BENTLEY (2012). HENRY HALLAM REVISITED. The Historical Journal, 55, pp 453473 doi:10.1017/S0018246X1200009X Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © Cambridge University Press doi:./SXX HENRY HALLAM REVISITED MICHAEL BENTLEY University of St Andrews ABSTRACT. Although Henry Hallam (–) is best known for his Constitutional History of England () and as a founder of ‘whig’ history, to situate him primarily as a mere critic of David Hume or as an apprentice to Thomas Babington Macaulay does him a disservice. He wrote four substantial books of which the first, his View of the state of Europe during the middle ages (), deserves to be seen as the most important; and his correspondence shows him to have been integrated into the contemporary intelligentsia in ways that imply more than the Whig acolyte customarily portrayed by commentators. This article re-situates Hallam by thinking across both time and space and depicts a significant historian whose filiations reached to Europe and North America. It proposes that Hallam did not originate the whig interpretation of history but rather that he created a sense of the past resting on law and science which would be reasserted in the age of Darwin. -

Clevedon Skyline Circular Walk Clevedon Is

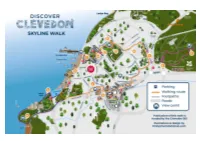

Skyline Walk Clevedon offers some spectacular views of town, coast and channel. This walk starts in the Alexandra road area. If you are driving, please park considerately. Make your way into the park known as Pier Copse. Take the steps up from in front of the kiosk and admire the views from the terrace above. STOP 1. The Sunset Terrace. After the end of the First World War an Austrian howitzer was given to Clevedon as a war relic. For many years it was located at the top end of 1 Pier Copse overlooking Clevedon’s beautiful Grade 1 listed Pier. Nowadays the terrace is a popular spot for enjoying sunsets and views of the grade 1 listed Pier and the Bristol Channel. The old gun is long gone. STOP 2. Drop down onto the seafront, turn left and walk along the promenade towards the Bandstand. This was built in 1887 to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. After passing the famously windswept yew tree and a pebbly beach you soon come to Salthouse Fields, where salt was panned in years gone by and, on the other side of the sea wall, Clevedon’s famous Marine Lake, the largest infinity pool in the world! 2 The direct route takes you from the Salthouse fields to Victoria Road and Point 5 The longer route now follows Poets’ Walk, which is well signposted. So, at the end of the promenade, start to climb the broad steps in front of you, beside the Salthouse Pub. After the first few steps, turn right along the wide path through the trees - still above the Marine Lake. -

Trades. [Somerset

698 F'AR TRADES. [SOMERSET. FARMERS continued. Collins Henry John, Coxley, Wells. Oorp J. Barton St. David, Taunton Clothier Waiter M. Lamyat, Bath Collins Herbert H. Knighton Sutton, Carp, Thomas, Rock house, Stoney Coaker Mrs. Franci.s W. Whitcomb, Stowey, Bristol Stratton, Bath Carton Denham,Sherborne (Dorset) Collins john, The Firs, Higher Corp Waiter, Sticklinch, West Pen-<,- Coaker Henry, Queen Camel, Bath Horton, Ilminster nard. Glastonbury Coate Robert & Son, Sedgemoor, Collins John, 'l'imberscombe, Taunton Corp William Henry, Sutt.an, Bath. Burrowbridge, Bridgwater Collins John Gritton, Wellow, Bath Cossinll F~ancis, Pitney, Langport. Coate Charles Dare, Helland, North Collins John William, Stonehouse, Cossins Samuel, Littleton, Somerton ) Curry, Taunton Mudfo·rd road, Yeovil Cottey John, Churchinford, Honiton Coate Rt. Geo. Broomfield, Bridgwatr Collins Saml. Moorlinch, Bridgwater Cottey Samuel, Curland, Taunton Coa.te Sidney, Stathe, Burrowbridge, Collins Thomas, Chaves Folly, Farm- Cattle Frank & Ernest, Milton, Wes- Bridgwater borough, Bath ton-super-Mare Cobb Henry, Blagdon, Bdstol Collins W, Cheddon Fitzpaine,Tauntn Cattle Henry, Moore lane, Clevedon Cobden H. Burst Bridge ho.Martock Collins W. Colc Style, Pitcombe, Bath Cattle J. Chelvey crt. Chelvey, Bristol Qock John, Clewer, Cheddar Collins Wltr. Nth. Brewham, Bruton Cattle Thomas, Havyatt, West Pen· Cock John, Wick, Lympsham,Weston- Collins William, Selwood, Frame nard, Glastonbury super-Mare Collins Wm.Wyke Champflower,Brutn Cottltj William, Binegar, Bath Cock Thomas, Priors wood, Taunton Colthurst A. Wt:>st end, Nailsea, Brstl Cotton Robert W. Coxbridge, West Cockram Frederick & John, Bickham, Oomer & Co. Mark, Highbridge Pennard, Glastonbury Timberscombe, Taunton Comer E. Blackford, Cheddar Couch Fdk.Wm.(dairy),Halse, Tauntn Cockram William, Culver street, Sto- Corner Mrs. -

Autumn 2012 Issue No

The Clevedonian Autumn 2012 Issue No. 06 In this edition LIvery Trip To London Page 2 A View from the Chair Group Report - Footpaths Group Page 3 Group Reports Environment Group Local History Group Page 4 Group Report - Conservation Group Coming Shortly Page 5 Livery Trip to London Page 6, 7 & 8 Rebuilding Clevedon Pier Page 9 Whiteladies Cottage Page 10 & 11 After Hugh Stebbing’s interesting Picnic at Clevedon Court February talk about the London Page 12 Livery Companies he offered to Entertainment in Clevedon take a group on a visit to the City of Page 13 London for a walk around the area. Transition Clevedon Page 14 The Four Brothers Page 15 Society Publications See page five for Wendy Moore’s Page 16 detailed account of the trip Neighbourhood Watch What’s in a Name Derek Lilly’s Wordsearch Page 17 Branch Line Page 18 Postcard from Clevedon Collector’s Lot Page 19 Military Chest Don’t Believe Everything You See! Page 20 Members’ Photograph Gallery Artist’s Attic The views expressed are those of the authors, and may or may not represent those of the Society. www.clevedon-civic-society.org.uk/ A View from The Chair Report by Hugh Stebbing Environment Group GrouP REporTs an it really be that we’re rapidly Meanwhile 2012 has seen an equally Planning Groups as well Report by Bob Hardcastle (Tel. 871633) Capproaching the end of another interesting programme both in the as with North Somerset year? Autumn winds and rain and Society and through those issues where Council. But I do sense to working with the Council in preparing Our regular monthly working party has increasing numbers of adverts for our opinions and experience have there’s more that can the Stage 2 submission. -

Tickenham, Where the Court Was Inspected. Tickenham Court

34 Thirty-third Annual Meeting . cess of demolition had been going on for at least 1200 years, it was no wonder that other remains besides Roman things were found. The Rev. H. H. Winwood suggested that the discovery Mr. Earle made, some time ago, might throw some light on the matter. The destruction might have taken place between the departure of the Romans and the incoming of the Saxons. That would give them a sort of approximate idea. The Rev. Dr. Hardman, Lecturer of Yatton Church, next gave some notes on that building, as printed in Part II. Mr. Green said he missed the western gallery that was in the church when they visited it twenty years ago. It was a fine example, and was put up by Lysons, the antiquary. It was so perfect an imitation of ancient work that it even deceived antiquaries as to its date. Dr. Hardman said the gallery had been removed. The President having thanked Dr. Hardman, next called upon Mr. J. Morland who read a paper on “ A Roman road between Glastonbury and Street.” Mr. Morland’s paper will be found in Part II. The Rev. H. H. Winwood objected to the name Roman as applied in this case, but time being very short there was unfortunately no discussion. The President having thanked Mr. Morland, called on Mr. George, who read a short biographical notice of Judge Choke of Long Ashton. The Chairman having thanked Mr. George for his paper, the meeting then terminated, soon after ten o’clock. The morning was fine, and a large party assembled at the Public Hall at ten o’clock. -

Tidal Reach CLEVEDON • NORTH SOMERSET

Tidal Reach CLEVEDON • NORTH SOMERSET Tidal Reach CLEVEDON • NORTH SOMERSET A stunning contemporary house with breath taking views across the Bristol channel Entrance hall • Kitchen/dining/sitting room Drawing room • Utility room • W/C Master bedroom suite with dressing room and en-suite bathroom Bedroom 2 with en-suite bathroom • Bedroom 3 with en-suite Bedroom 4 with en-suite shower room • Study/bedroom 5 Swimming pool • Gym • Shower/Changing Room Plant room • Garage • Large terrace Bristol 15 miles • M5 (J20) 2 miles • Bristol Airport 12 miles Nailsea & Backwell Railway Station 7.5 miles Bristol Temple Meads Railway Station 14 miles (All distances are approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation Tidal reach is situated in an elevated position at the end of a private no through road. There are commanding views over the Bristol Channel to the Welsh Hills as well as Clevedon Pier and beyond. Tidal Reach is within a short distance, about 0.3 of a mile, of the popular and fashionable Hill Road area where there is a selection of a number of shops including restaurants and boutiques. The town centre provides a comprehensive range of shops including supermarkets and banks. The Mall at Cribbs Causeway is about 14 miles. Lovely walks along the Coastal Path including Poet’s Walk. Sailing and fi shing on Chew Valley Lake. Walking and riding over the Mendip Hills. Racing at Bath and Wincanton. -

Clevedon Court

CLEVEDON COURT After 1066, the Manor of Clevedon was granted to Matthew Mortagne whose family probably changed their name to de Clevedon before the middle of the twelfth century. By 1296, the manor was held by John de Clevedon. It is thought he built the house incorporating the mid-thirteenth century tower into the battlements. Edmund de Clevedon died in 1376 and his second wife Alice was entitled to a third of her late husband’s income for the rest of her life. There are four medieval court rolls relating to this period in the British Library, dated 1321, 1389, 1390 and 1397. The rolls give a fascinating insight to life in fourteenth century Somerset although there is little about the house or garden. The Dower Document which is attached to the 1389 roll, states Alice’s assets: And there is also there one dovecote that is worth per annum 5s. Item 1/3 part of the lord’s mill and worth per annum 15s 61/2d. Item one garden called west garden that is worth per annum 18d. Item 1 virgate price 10d. Item 1.3 part of pasture in the park worth 20d. Item 1.3 part of a wood on Northdon containing 10 acres price [per?] acre at present 6s 8d if sold and Item 1.3 part of a wood on Calso containing 2 acres 1 rood price [er?] acre 2s_ _ _ pasture none which [is] of no value. In the fourteenth century, the de Clevedon’s would have spoken French, the villagers Middle English while important documents were written in Latin. -

Bibliography Sources for Further Reading May 2011 National Trust Bibliography

Bibliography Sources for further reading May 2011 National Trust Bibliography Introduction Over many years a great deal has been published about the properties and collections in the care of the National Trust, yet to date no single record of those publications has been established. The following Bibliography is a first attempt to do just that, and provides a starting point for those who want to learn more about the properties and collections in the National Trust’s care. Inevitably this list will have gaps in it. Do please let us know of additional material that you feel might be included, or where you have spotted errors in the existing entries. All feedback to [email protected] would be very welcome. Please note the Bibliography does not include minor references within large reference works, such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica, or to guidebooks published by the National Trust. How to use The Bibliography is arranged by property, and then alphabetically by author. For ease of use, clicking on a hyperlink will take you from a property name listed on the Contents Page to the page for that property. ‘Return to Contents’ hyperlinks will take you back to the contents page. To search by particular terms, such as author or a theme, please make use of the ‘Find’ function, in the ‘Edit’ menu (or use the keyboard shortcut ‘[Ctrl] + [F]’). Locating copies of books, journals or specific articles Most of the books, and some journals and magazines, can of course be found in any good library. For access to rarer titles a visit to one of the country’s copyright libraries may be necessary. -

Clevedon Court Access Statement

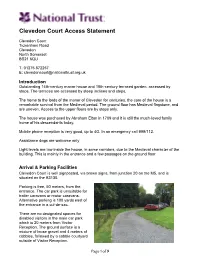

Clevedon Court Access Statement Clevedon Court Tickenham Road Clevedon North Somerset BS21 6QU T: 01275 872257 E: [email protected] Introduction Outstanding 14th-century manor house and 18th-century terraced garden, accessed by steps. The terraces are accessed by steep inclines and steps. The home to the lords of the manor of Clevedon for centuries, the core of the house is a remarkable survival from the Medieval period. The ground floor has Medieval flagstone, and are uneven. Access to the upper floors are by steps only. The house was purchased by Abraham Elton in 1709 and it is still the much-loved family home of his descendants today. Mobile phone reception is very good, up to 4G. In an emergency call 999/112. Assistance dogs are welcome only Light levels are low inside the house, in some corridors, due to the Medieval character of the building. This is mainly in the entrance and a few passages on the ground floor. Arrival & Parking Facilities Clevedon Court is well signposted, via brown signs, from junction 20 on the M5, and is situated on the B3130. Parking is free, 50 meters, from the entrance. The car park is unsuitable for trailer caravans or motor caravans. Alternative parking is 100 yards east of the entrance in a cul-de-sac. There are no designated spaces for disabled visitors in the main car park which is 20 meters from Visitor Reception. The ground surface is a mixture of loose gravel and 4 meters of cobbles, followed by a cobble courtyard outside of Visitor Reception.