Education Guide – Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Giopulos Files on Campus

Peter Giopulos Collection Artist Files Box A-B Folder # 1 – Art on Campus intro Folder # 2 – Art Walk Map Folder # 3 – Web Art Bill Stewart Folder # 4 – Art on Campus (A) Ansel Adams Samuel Marcus Adler George Gustave Adomeit Ahlgren, Roy B Charles Curtis Adams Frank Milton Armington Milton Clark Avery Folder # 5 – Josef Albers Folder # 6 – Mari Alexander Folder # 7 – Architecture on campus Folder # 8 – Harry Bertoia Folder # 9 – Art on campus (B) Otto Henry Bacher Federico Fiori Barocci Norman Arthur Bate Will Barnet Gustave Baumann Lester Beall Frank Weston Benson Thomas Hart Benton Alistair Bevington Sander Blondeel Milton Bond Walter H Cassebeer Borglum, Gutzon Philip Bornarth Charlotte Bowman Folder # 10 – Donald Bujnowski Doors Folder # 11 – Photo printed from collection Bujnowski 11 copies of 8x11 photographs of his work Box C-F Folder # 1 – Art on Campus C Robert Carter Walter H Cassebeer Wendell Castle John Channell Philip Cheney Ohi Chozaemon Carl Chiarenza John Scott Clubb Eugene C. Colby Robert Conge, Lila Copeland John Edwards Costigan James Crable Frank Craig Byron G Culver Folder # 2 – Augustus Wall Callcott Folder # 3 – Hans Christensen Folder # 4 – Art on campus [D-F] Henry Golden Dearth Henry De Maine Jose De Rivera David Dickinson Mitsui Eiichi Alejandro Fernandez Robert Fergerson Richard Aberle Florsheim Emil Fuchs Folder # 5 – Eisenhower dresses & Paintings in stage – Physical plant Folder # 6 – Harold (Hal) Foster Folder # 7 – Donald J Forsythe Box G-L Folder # 1 – Dan Kiley Folder # 2 – Art on Campus (G-H) Emil Ganso Moton Garchik Charles Dana Gibson Arthur Eric Rowton Gill Janet Goldner Nancy Gong Marion Greenwood Emile Albert Gruppe, Folder # 3 – Gordon Grant Folder # 4 – Gordon, Stanley Folder # 5 – Art on Campus (H) Silvanus G. -

Oral History Interview with Michael W. Monroe

Oral history interview with Michael W. Monroe Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Michael W. Monroe AAA.monroe18 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Michael W. Monroe Identifier: AAA.monroe18 Date: 2018 January 22-March 1 Creator: Monroe, Michael W. (Interviewee) Herman, Lloyd E. Extent: 8 Items (sound files (3 hr., 59 min.) Audio; digital, wav) 71 Pages (Transcript) Language: English . Digital Digital Content: Oral history interview with Michael W. Monroe, -

Craft Alliance Center for Art and Design Records (S0439)

PRELIMINARY INVENTORY S0439 (SA0010, SA2390, SA2492, SA2714, SA3035, SA3068, SA3103, SA3633, SA3958) CRAFT ALLIANCE CENTER FOR ART AND DESIGN RECORDS This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center- St. Louis. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Introduction Approximately 58 cubic feet The Craft Alliance is a non-profit, cultural and educational organization which promotes the production, enjoyment, and understanding of the crafts. The records include budgets, bylaws, correspondence, exhibition schedules, Education Center program schedules, newsletters, scrapbooks, and photographs. Donor Information The records were donated to the University of Missouri by Mrs. Norman Morse on January 29, 1971 (Accession No. SA0010). Additions were made on April 7, 1981 by a representative of the Craft Alliance (Accession No. SA2930); November 2, 1982 by Mary Colton (Accession No. SA2492); September 11, 1985 by Wilda Swift (Accession No. SA2714); December 1, 1991 by Barbara Jedda (Accession No. SA3035); June 24, 1992 by Barbara Jedda (Accession No. SA3068); December 28, 1992 by Barbara Jedda (Accession No. SA3103); September 7, 2005 by Alexi Glynias (Accession No. SA3633); July 12, 2011 by Barbara Jedda (Accession No. SA3958); August 14, 2020 by Mark Witzling (Accession No. SA4474); August 26, 2020 by Mark Witzling (Accession No. SA4479). Copyright and Restrictions The Donor has given and assigned to the State Historical Society of Missouri all rights of copyright which the Donor has in the Materials and in such of the Donor’s works as may be found among any collections of Materials received by the Society from others. -

Craft in America Mission Statement 3

CRAFT INeducators AMERICA guide: memory Sam Maloof, Double Rocker, Gene Sasse Photo 1 contents introduction Craft in America Mission Statement 3 Craft in America, Inc. 3 Craft in America: The Series 3 Viewing the Series 3 Ordering the DVD and Companion Book 3 Audience 3 Craft in America Educator Guides 4 How to Use the Guides 4 Scope and Sequence 4 themes Fragments 5 Roots 12 Hand to Home 19 Worksheets 26 Additional Web Resources 36 Credits & Copyright 37 2 educator guide information Craft in America, Inc. Craft In America Inc. is a non-profit organization dedicated to the exploration of craft in the United States and its impact on our nation’s cultural heritage. The centerpiece of the company’s efforts is the production of a nationally broadcast television documentary series celebrating American craft and the artists who bring it to life. The project currently includes a three-part television documentary series supported by CRAFT IN AMERICA: Expanding Traditions, a nationally touring exhibition of exceptional craft objects, as well as a companion book, and a comprehensive Web site. Carol Sauvion is the founder and director of Craft in America. Craft in America Mission Statement The mission of Craft in America is to document and advance original handcrafted work through programs in all media made accessible to all Americans. Craft in America: The Series Craft in America’s nationally broadcast PBS documentary series seeks to celebrate craft by honoring the artists who create it. In three episodes entitled Memory, Landscape and Community, Craft in America television viewers will travel throughout the United States visiting America’s premier craft artists in their studios to witness the creation of hand- made objects, and into the homes, businesses and public spaces where functional art is employed and celebrated. -

Acknowledgments from the Authors

Makers: A History of American Studio Craft, by Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf, published by University of North Carolina Press. Please note that this document provides a complete list of acknowledgments by the authors. The textbook itself contains a somewhat shortened list to accommodate design and space constraints. Acknowledgments from the Authors The Craft-Camarata Frederick Hürten Rhead established a pottery in Santa Barbara in 1914 that was formally named Rhead Pottery but was known as the Pottery of the Camarata (“friends” in Italian). It was probably connected with the Gift Shop of the Craft-Camarata located in Santa Barbara at that time. Like his pottery, this book is not an individual achievement. It required the contributions of friends of the field, some personally known to the authors, but many not, who contributed time, information and funds to the cause. Our funders: Windgate Charitable Foundation / The National Endowment for the Arts / Rotasa Foundation / Edward C. Johnson Fund, Fidelity Foundation / Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund / The Greenberg Foundation / The Karma Foundation / Grainer Family Foundation / American Craft Council / Collectors of Wood Art / Friends of Fiber Art International / Society of North American Goldsmiths / The Wood Turning Center / John and Robyn Horn / Dorothy and George Saxe / Terri F. Moritz / David and Ruth Waterbury / Sue Bass, Andora Gallery / Ken and JoAnn Edwards / Dewey Garrett / and Jacques Vesery. The people at the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design in Hendersonville, N.C., administrators of the book project: Dian Magie, Executive Director / Stoney Lamar / Katie Lee / Terri Gibson / Constance Humphries. Also Kristen Watts, who managed the images, and Chuck Grench of the University of North Carolina Press. -

Five-Year Report

five-year report Letter From the Board Chair Dear Friends, he 5th anniversary of our new home interdisciplinary mix, from workshops and is an extraordinary moment for the tours to performances and screenings. Museum of Arts and Design. With a Growing our permanent collection three- dynamic roster of exhibitions and fold, under Holly and David’s leadership, allows programs planned, a loyal base of us to offer richer and deeper exhibitions for our friends and supporters and new visitors. Encompassing traditional forms of Lewis Kruger leadership at the helm, we couldn’t craftsmanship, including works made in clay, chairman, board of trustees; be more excited about all that we glass, wood, metal and fiber, as well as works museum of have ahead. Together with our of art and design created with innovative new arts and design dedicated board, so many important donors, materials and processes, the collection now Tour 8,000-strong base of loyal members and our establishes a bridge between legendary craft talented staff, it has been a remarkable process figures and a new generation of makers. to build not just a new building, but a new It is fully digitized and can be accessed online institution. I want to thank Holly Hotchner, who by our global community as well as through led the Museum for 16 years before stepping innovative in-gallery formats, as so many down this spring, and our chief curator David of you have experienced. McFadden, who will be retiring at the end of Our robust special exhibition program this year after a 16-year tenure; as well as my has transformed traditional ideas about craft, fellow members of our board trustees, especially including a series of critically acclaimed Jerome A. -

Kilns • Kiln Kits

.o . ,~° D J D 0 o • • • ° °/ ~p "m s i°e ° e -4" v P # ,I °o B* • t WF, STWqlDqDID CEI AMIC, SlIIDIDILY COMIDA Y IDn-i tluuees Vau-ie/ies iJf tonne ,;nn-e Clays!* So when you come to us for clay, be ready with the specifics! We can supply you with a clay which will suit your most exacting needs. WESTWOOD CERAMIC SUPPLY CO. 14400 LOMITAS AVE.. CITY OF INDUSTRY. CALIF. 91"744 THROWING ON THE Decorating POTTER'S Throwing Potter's Pottery on the Wheel with Clay, NH£F'L Potter's Projects Slip & Glaze Wheel edited by by Thomas Sellers Thomas Sellers by F. Carlton Ball This beautifully illustrated book ex- A complete manual on how to use The projects in this handbook pro- the potter's wheel. Covers all basic vide step-by-step instruction on a plores many easy methods of deco- rating pottery with clay, slip and steps from wedging clay to making wide variety of special throwing specific shapes. Clearly describes techniques, with each project demon- glaze. Those who lack skill and confidence in drawing and painting every detail using step-by-step photo strated by an accomplished crafts- technique. Includes section on selec- man. Bells, bird houses and feeders, will find special pleasure in discov- ering the easily executed decorating tion of the proper wheel and acces- musical instruments, teapots, and a text in many you'll techniques devised by this master sory tools. Used as animals are just a few items colleges and schools. 80 pages $4.00 find presented. -

CRAFT in Americacommunity: Show Me

CRAFT IN AMERICAcommunity: show me Preview Craft forms known to us to today would not exist if it were not for the artists. For thousands of years they have carried on tradi- tions; some remain true to long established practice while others add their own twist. In this section of Educator Guide: Com- munity, students will learn that artists such as Mary Jackson and instructors at craft schools like Penland School of Craft have an innate desire to share what they have learned. Artists and schools like these function with the understanding that in order for craft traditions to exist in the future, they must share what they know. They must teach others. Featured Artists Penland School of Craft (fiber/Community) Mary Jackson (basket maker/Memory) Related Artists Mira Nakashima (wood/Landscape) Denise Wallace (jewelry/Community) 1 contents show me Introduction 5 Penland School of Craft 6 Mary Jackson 7 The Craft Connection 8 Craft in Action 9 Craft in the Classroom 10 Make 11 Worksheets 12 Additional Web Resources 36 Credits & Copyright 37 2 education guide information Craft in America, Inc. Craft In America Inc. is a non-profit organization dedicated to the exploration of craft in the United States and its impact on our nation’s cultural heritage. The centerpiece of the company’s efforts is the production of a nationally broadcast television documentary series celebrating American craft and the artists who bring it to life. The project currently includes a three-part television documentary series supported by CRAFT IN AMERICA: Expanding Traditions, a nationally touring exhibition of exceptional craft objects, as well as a companion book, and a comprehensive Web site. -

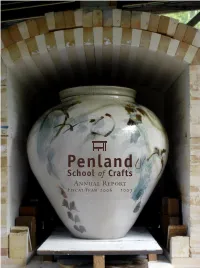

Fiscal Year 2007 Annual Report (PDF)

Penland School of Crafts Annual Report Fiscal Year 2006 – 2007 Penland’s Mission The mission of Penland School of Crafts is to support individual and artistic growth through craft. The Penland Vision Penland’s programs engage the human spirit which is expressed throughout the world in craft. Penland enriches lives by teaching skills, ideas, and the value of the handmade. Penland welcomes everyone—from vocational and avocational craft practitioners to interested visitors. Penland is a stimulating, transformative, egalitarian place where people love to work, feel free to experiment, and often exceed their own expectations. Penland’s beautiful location and historic campus inform every aspect of its work. Penland’s Educational Philosophy Penland’s educational philosophy is based on these core ideas: • Total immersion workshop education is a uniquely effective way of learning. • Close interaction with others promotes the exchange of information and ideas between individuals and disciplines. • Generosity enhances education—Penland encourages instructors, students, and staff to freely share their knowledge and experience. • Craft is kept vital by preserving its traditions and constantly expanding its boundaries. Cover Information Front cover: this pot was built by David Steumpfle during his summer workshop. It was glazed and fired by Cynthia Bringle in and sold in the Penland benefit auction for a record price. It is shown in Cynthia’s kiln at her studio at Penland. Inside front cover: chalkboard in the Pines dining room, drawing by instructor Arthur González. Inside back cover: throwing a pot in the clay studio during a workshop taught by Jason Walker. Title page: Instructors Meg Peterson and Mark Angus playing accordion duets during an outdoor Empty Bowls dinner. -

Jeannine Falino's CV

JEANNINE FALINO Curator, writer, and lecturer examining the intersection of design, craft and society CURATORIAL PROJECTS Exhibition Curator Curator, Betty Cooke: The Circle and The Line, Walters Art Museum. Exhibition forthcoming fall 2021; catalogue forthcoming September 2020. Curator, Gilded Chicago: Portraits of an Era, The Richard H. Driehaus Museum. A companion exhibition to Beauty’s Legacy, Gilded Age Portraiture in America, focusing on prominent Chicago citizens and the portraits they commissioned to advance their social standing and proclaim their affluence. September 2018 to January 2019 Curator, New York Silver, Then and Now, Museum of the City of New York. Twenty-four metalsmiths, artists, and designers create new works inspired by the Museum’s renowned collection of New York silver. June 2017 to May 2018 Curator, L’Affichomania: The Passion for French Posters, The Richard H. Driehaus Museum, Chicago, Illinois. Five grand masters of the medium (Jules Chéret, Eugène Grasset, Théophile- Alexandre Steinlen, Alphonse Mucha, Henri de Toulouse Lautrec) are featured, with one gallery devoted to performances advertised in this new art form, and accompanied by Acoustiguide script. For catalogue, see publications. February 2017 to January 2018 Curator, What Would Mrs. Webb Do? A Founder’s Vision, Museum of Arts and Design, New York. Focus on Aileen Osborn Webb as an advocate and philanthropist in American craft. September 2014 to February 2015 Co-curator, Gilded New York, Design, Fashion & Society, Museum of the City of New York. Exhibition devoted to luxury goods and paintings in New York’s gilded age. For catalogue, see publications. March 2012 to May 2017 Co-curator, Crafting Modernism: Midcentury American Art and Design, Museum of Arts and Design, New York. -

James Gros See Page 2

era Publi calton of the American Crafts Council James Gros See page 2 Second Class Postage Paid at New York, NY and at Additional Mailing Office . ... - ".-.- . _. _._.- ._-_._--_._._----_._-------- CRAFT WORLD of Craft Horizons ACC NEWS Vol. XXXVIII No.4 Rose Slivka, Safari Off Editor-in-Chief Patricia Dandignac , OPEN to Africa Managing Editor Michael Lauretano, DOOR Fertility dolls and ceremonial Art Director Samuel Scherr masks, metalsmithing and pot Edith Dugmore, tery-these are some highlights Assistant Editor As of the April issue, you may of "The Art and Tradition of Michael McTwigan, have noticed that I revised the Editorial Assistant West Africa," a three-week tour heading of this column from of Senegal, Ghana, Togo, and Ni Isa bella Brandt, " Open Windows" to " Open Editorial Assistant geria (August 2-27, 1978, and Door," since I felt strongly that Anita Chmiel, January 7-31,1979). Sponsored Advertising Department the ncw and proper direction of by ACC and Art Safari, Inc., the the American Crafts Council tour is led by Art Safari codirec Editorial Board should invite an easy access to Junius Bird tor James Gross and fiber artist Jean Delius Arline Fi sc h the flow of information and ideas, Eleanor Dickinson. For the Au Persis Grayson not only within the U.S. but also gust tour contact, posthaste: 1924-1978 Robert Beverly Hale abroad. An open door is an invi Steven Adler, 800-223-0694, toll Lee Hall tation to exchange and growth. frce; or write ACC/ Art Safari. Pol ly Lada-Mocarski Another equally significant Jean Delius, jcweler and associate Harvey Littleton change is this month's CRAFT professor at New York State Col Ben Ra eburn HORIZONS with its section of lege at Oswego, died suddenly Ed Rossbach CRAFT WORLD. -

Oral History Interview with Thomas Gentille, 2009 August 2-5

Oral history interview with Thomas Gentille, 2009 August 2-5 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Thomas Gentille on 2009 August 2. The interview took place in New York, NY, and was conducted by Ursula Ilse-Neuman for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Thomas Gentille and Ursula Ilse-Neuman have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview PROLOGUE [added by Thomas Gentille after the interview]: [Film director Michelangelo] Antonioni once told [Mark] Rothko: "Your paintings are like my films - they're about nothing . with precision." [From Jeffrey Weiss, "Temps Mort: Rothko and Antonioni," in Mark Rothko, ed. Oliver Wick (New York: Skira, 2008).] URSULA ILSE-NEUMAN: This is Ursula Ilse-Neuman interviewing Thomas Gentille at his home on East 64th Street in New York [NY] on August 2, 2009. I’m conducting this interview for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This is disc number one. Thomas, you have been one of the leaders in the field of American studio jewelry since the late 1950s. You also have been especially revered and honored in Europe.