Identifying Young People at Risk of Developing Psychosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia

Reward Processing Mechanisms of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Gregory P. Strauss, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Department of Psychology University of Georgia Disclosures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS & DISCLOSURES ▪ Receive royalties and consultation fees from ProPhase LLC in connection with commercial use of the BNSS and other professional activities; these fees are donated to the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. ▪ Last 12 Months: Speaking/consultation with Minerva, Lundbeck, Acadia What are negative symptoms and why are they important? Domains of psychopathology in schizophrenia Negative Symptoms ▪ Negative symptoms - reductions in goal-directed activity, social behavior, pleasure, and the outward expression of emotion or speech Cognitive Positive ▪ Long considered a core feature of psychotic disorders1,2 Deficits Symptoms ▪ Distinct from other domains of psychopathology (e.g., psychosis, disorganization) 3 ▪ Associated with a range of poor clinical outcomes (e.g., Disorganized Affective disease liability, quality of life, subjective well-being, Symptoms Symptoms recovery) 4-7 1. Bleuler E. [Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias]. Vertex Sep-Oct 2010;21(93):394-400. 2. Kraepelin E. Dementia praecox and paraphrenia (R. M. Barclay, Trans.). New York, NY: Krieger. 1919. 3. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. How many and which are the psychopathological dimensions in schizophrenia? Issues influencing their ascertainment. Schizophrenia research Apr 30 2001;49(3):269-285. 4. Fervaha G, Remington G. Validation of an abbreviated quality of life scale for schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol Sep 2013;23(9):1072-1077. 5. Piskulic D, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, et al. Negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Psychiatry research Apr 30 2012;196(2-3):220-224. -

The Clinical Presentation of Psychotic Disorders Bob Boland MD Slide 1

The Clinical Presentation of Psychotic Disorders Bob Boland MD Slide 1 Psychotic Disorders Slide 2 As with all the disorders, it is preferable to pick Archetype one “archetypal” disorder for the category of • Schizophrenia disorder, understand it well, and then know the others as they compare. For the psychotic disorders, the diagnosis we will concentrate on will be Schizophrenia. Slide 3 A good way to organize discussions of Phenomenology phenomenology is by using the same structure • The mental status exam as the mental status examination. – Appearance –Mood – Thought – Cognition – Judgment and Insight Clinical Presentation of Psychotic Disorders. Slide 4 Motor disturbances include disorders of Appearance mobility, activity and volition. Catatonic – Motor disturbances • Catatonia stupor is a state in which patients are •Stereotypy • Mannerisms immobile, mute, yet conscious. They exhibit – Behavioral problems •Hygiene waxy flexibility, or assumption of bizarre • Social functioning – “Soft signs” postures as most dramatic example. Catatonic excitement is uncontrolled and aimless motor activity. It is important to differentiate from substance-induced movement disorders, such as extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia. Slide 5 Disorders of behavior may involve Appearance deterioration of social functioning-- social • Behavioral Problems • Social functioning withdrawal, self neglect, neglect of • Other – Ex. Neuro soft signs environment (deterioration of housing, etc.), or socially inappropriate behaviors (talking to themselves in -

Introduction to Agitation, Delirium, and Psychosis Curriculum for Psychologists/Social Workers

FACILITATOR MANUAL ENGLISH-HAITI Introduction to Agitation, Delirium, and Psychosis Curriculum for Psychologists/Social Workers Introduction to Agitation, Delirium, and Psychosis Curriculum for Psychologists/Social Workers Partners In Health (PIH) is an independent, non-profit organization founded over twenty years ago in Haiti with a mission to provide the very best medical care in places that had none, to accompany patients through their care and treatment, and to address the root causes of their illness. Today, PIH works in fourteen countries with a comprehensive approach to breaking the cycle of poverty and disease — through direct health-care delivery as well as community-based interventions in agriculture and nutrition, housing, clean water, and income generation. PIH’s work begins with caring for and treating patients, but it extends far beyond to the transformation of communities, health systems, and global health policy. PIH has built and sustained this integrated approach in the midst of tragedies like the devastating earthquake in Haiti. Through collaboration with leading medical and academic institutions like Harvard Medical School and the Brigham & Women’s Hospital, PIH works to disseminate this model to others. Through advocacy efforts aimed at global health funders and policymakers, PIH seeks to raise the standard for what is possible in the delivery of health care in the poorest corners of the world. PIH works in Haiti, Russia, Peru, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Liberia Lesotho, Malawi, Kazakhstan, Mexico and the United States. For more information about PIH, please visit www.pih.org. Many PIH and Zanmi Lasante staff members and external partners contributed to the development of this training. -

Schizophrenia- What You Need to Know

SCHIZOPHRENIA- WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW BY CATHY CYWINSKI, MSW LCSW SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF SCHIZOPHRENIA • Hallucinations- false perception • Delusions –fixed false belief • Grossly Disorganized Speech and Behavior • Tend to dress and act in odd ways • Flat Affect SYMPTOMS • Hallucinations-can occur with any of the five senses: • Auditory hallucinations • Visual hallucinations • Tactile hallucinations • Olfactory hallucinations • Gustatory hallucinations SYMPTOMS • Bizarre delusion – this simply translated means a delusion regarding something that CANNOT possibly happen. • Nonbizarre delusion – this is a delusion regarding something that CAN possibly happen. COMMON TYPES OF DELUSIONS • Grandiose • Erotomanic • Religious • Delusions of Control • Persecutory • Referential SYMPTOMS • Disorganized Speech • Loose associations- may go from one topic to another with no clear logic • Tangentiality- answers to questions may be obliquely related or completely unrelated • Incoherence or word salad- speech may be so severely disorganized that it is nearly incomprehensible SYMPTOMS • Grossly disorganized behavior • A person may appear disheveled, may dress in an unusual manner (many layers of clothes on a hot day), or may display inappropriate sexual behavior. • Alogia-poverty of speech- brief, empty replies • Avolition- inability to initiate and persist in goal directed activates. The person may sit for long periods of time and show little interest in participating in work or social activities. • Catatonic motor behaviors- a marked decrease in reactivity to the environments. SYMPTOMS • Negative Symptoms • Affect flattening- a person’s face appearing immobile and unresponsive, with poor eye contact and reduced body language IS THERE SOMETHING TO FEAR • Myth: People with a severe mental illness are violent and unpredictable. • Fact: The vast majority of people with mental health problems are no more likely to be violent than anyone else. -

The Differential Diagnosis of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness And

Case Reports The Differential Diagnosis of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness and Cognitive Deficits in a Patient with Delirium, Schizophrenia and Possible Narcolepsy: A Case Report David R. Spiegel 1, Parker W. Babington 1, Ariane M. Abcarian 1, Christian De Filippo 1 Abstract Narcolepsy and schizophrenia are disorders which share common features of negative symptoms, excessive daytime sleepiness and cognitive deficits. Presented here is a case report of a fifty-nine year old man with a past medical history of schizophrenia who was evaluated for suspected symptoms of delirium. After an electroencephalogram was per- formed with surprising results, the patient’s differential diagnosis included schizophrenia with comorbid narcolepsy. We present emerging evidence that excessive daytime sleepiness and attentional deficits in both narcolepsy and schizo- phrenia may share a common pathophysiological pathway through orexin deficiency and its effects on the dopamine system. Finally, we discuss the potential for modafinil as a treatment for excessive daytime sleepiness and attentional problems in schizophrenia and narcolepsy. Key Words: Cognition, Schizophrenia, Sedation, Sleep, Dopamine Introduction The hallmarks of delirium as described by the Diagnostic including the positive symptoms of delusions, hallucina- and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, tions, disorganized speech and grossly disorganized or cata- Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) are a disturbance of conscious- tonic behavior, and negative symptoms such as flattened af- ness with reduced ability to focus, sustain or shift attention. fect, alogia and avolition (1). Patients with schizophrenia Also present is a change in cognition, such as memory defi- also have cognitive deficits, including poor attention span. cit, disorientation or language impairment, or a perceptual Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep onset disorders such disturbance. -

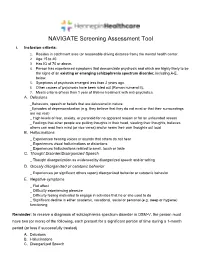

NAVIGATE Screening Assessment Tool

NAVIGATE Screening Assessment Tool I. Inclusion criteria: 1. Resides in catchment area (or reasonable driving distance from) the mental health center. 2. Age 15 to 40. 3. Has IQ of 70 or above. 4. Person has experienced symptoms that demonstrate psychosis and which are highly likely to be the signs of an existing or emerging schizophrenia spectrum disorder, including A-E, below. 5. Symptoms of psychosis emerged less than 2 years ago. 6. Other causes of psychosis have been ruled out (Roman numeral II). 7. Meets criteria of less than 1 year of lifetime treatment with anti-psychotics. A. Delusions _Behaviors, speech or beliefs that are delusional in nature _Episodes of depersonalization (e.g. they believe that they do not exist or that their surroundings are not real) _ High levels of fear, anxiety, or paranoid for no apparent reason or for an unfounded reason _ Feelings that other people are putting thoughts in their head, stealing their thoughts, believes others can read their mind (or vice versa) and/or hears their own thoughts out loud B. Hallucinations _ Experiences hearing voices or sounds that others do not hear _ Experiences visual hallucinations or distortions _ Experiences hallucinations related to smell, touch or taste C. Thought Disorder/Disorganized Speech _ Thought disorganization as evidenced by disorganized speech and/or writing D. Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior _ Experiences (or significant others report) disorganized behavior or catatonic behavior E. Negative symptoms _ Flat affect _ Difficulty experiencing pleasure _ Difficulty feeling motivated to engage in activities that he or she used to do _ Significant decline in either academic, vocational, social or personal (e.g. -

Negative Symptoms- an Update

Galore International Journal of Health Sciences and Research Vol.4; Issue: 1; Jan.-March 2019 Website: www.gijhsr.com Review Article P-ISSN: 2456-9321 Negative Symptoms- an Update Dr Pavithra P. Rao1, Dr Preethi Rebello2, Dr P. John Mathai3 1Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry. Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India. 2Senior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India. 3Professor. Department of Psychiatry, Jubilee Mission Medical College, East Fort Thrissur. Kerala. India. Corresponding Author: Dr P. John Mathai ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Negative symptoms (NS) are Negative Symptoms in psychiatry are deficits in abnormal absence of normal behaviour and experience and behavior that are attributed to experience, attributed to the loss of normal loss of functions of brain. Negative symptoms functions of the brain. The NS are defined have been conceptualized as the core aspect of as absence of experience/behaviour that schizophrenia and have been recognized as [1] important ever since the days of Griesinger, should have been present. They are Kraepelin and Bleuler. But over the years the general descriptive terms used for the significance of the negative symptoms was various clinical manifestations of the deleted and emphasis was placed almost diminished capacity for ordinary exclusively on positive symptoms. The return of behavioural functioning (behavioural negative symptoms in schizophrenia was deficits). [2] Though there are differences in inevitable. The five general categories of the language used to refer to NS such as, negative symptoms include avolition, deficits symptoms, defect state symptoms, anhedonia, affective blunting, alogia and type II symptoms, core symptoms, asociality. The subdomains of negative fundamental symptoms, primary symptoms symptoms are experience domain (avolition and and basic symptoms, there are definite anhedonia) and expressivity domain (affective [3-7] blunting and alogia). -

Deficits in Positive Reinforcement Learning and Uncertainty-Driven

Deficits in Positive Reinforcement Learning and Uncertainty-Driven Exploration Are Associated with Distinct Aspects of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Gregory P. Strauss, Michael J. Frank, James A. Waltz, Zuzana Kasanova, Ellen S. Herbener, and James M. Gold Background: Negative symptoms are core features of schizophrenia (SZ); however, the cognitive and neural basis for individual negative symptom domains remains unclear. Converging evidence suggests a role for striatal and prefrontal dopamine in reward learning and the exploration of actions that might produce outcomes that are better than the status quo. The current study examines whether deficits in reinforcement learning and uncertainty-driven exploration predict specific negative symptom domains. Methods: We administered a temporal decision-making task, which required trial-by-trial adjustment of reaction time to maximize reward receipt, to 51 patients with SZ and 39 age-matched healthy control subjects. Task conditions were designed such that expected value (probability ϫ magnitude) increased, decreased, or remained constant with increasing response times. Computational analyses were applied to estimate the degree to which trial-by-trial responses are influenced by reinforcement history. Results: Individuals with SZ showed impaired Go learning but intact NoGo learning relative to control subjects. These effects were most pronounced in patients with higher levels of negative symptoms. Uncertainty-based exploration was substantially reduced in individuals with SZ and selectively correlated with clinical ratings of anhedonia. Conclusions: Schizophrenia patients, particularly those with high negative symptoms, failed to speed reaction times to increase positive outcomes and showed reduced tendency to explore when alternative actions could lead to better outcomes than the status quo. -

Basic Considerations for Understanding, Diagnosing and Treating Symptoms of Primary Non-Dementia Psychosis in Older Adults

Geriatric Nursing 40 (2019) 220À224 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geriatric Nursing journal homepage: www.gnjournal.com GAPNA Section Basic considerations for understanding, diagnosing and treating symptoms of primary non-dementia psychosis in older adults Melodee Harris, PhD, APRN, GNP-BC, AGPCNP-BCa,*, Karen Devereaux Melillo, FAANP, PhD, FGSA, A-GNP-Cb, Linda J. Keilman, DNP, GNP-BC, FAANPc, George Byron Peraza-Smith, DNP, ARNP, GNP-BC, NP-C, CNE, GS-C, FAANd, Shirley Duane, CSRN, FNP-C, GS-C, CNRN,FNP-Ce, Marcia Walmer, DNP, RN, PMHNP-BC, LCSWf, Tamatha Arms, PhDc, DNP, PMHNP-BC, NP-Cg, Sharon Bronner, DNP, MSN, APRN, GNP-BC, ACHPNh, Cecilia A Nwogu, DNP, GNP-BC, PMHNPi, Amy M. Lewitz, MS, APRN, PMHCNS/BCj, Pamela Z. Cacchione, PhD, CRNP, BC, FGSA, FAANk a University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, College of Nursing, 4301 West Markham Street Slot #529, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA b Solomont School of Nursing, Zuckerberg College of Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Health and Social Sciences Building, Suite 200, 113 Wilder St., Office 215, Lowell, MA 01854-3058, USA c Michigan State University, College of Nursing, 1355 Bogue Street, A126 Life Science Building, East Lansing, MI 48824-1317, USA d United States University, 7675 Mission Valley Road, San Diego, CA 92108, USA e UBMD, Erie County Medical Center, 462 Grider Street, Buffalo, NY 14216, USA f University of Missouri- Kansas City, School of Nursing and Health Studies, Kansas City, MO 64108, USA g UNCW CHHS School of Nursing, McNeil office 2034A, Wilmington, NC, USA h Optum Care Supportive Care, One Penn Plaza 8th Floor, New York, NY 10119, USA i Adult Health Consultant of Atlanta Inc, 1941 Lancaster DR., Conyers, GA 30013, USA j Private Practice, 6942 N. -

Is Voice a Marker for Autism Spectrum Disorder? a Systematic Review

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/046565; this version posted June 24, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. TITLE: “Is voice a marker for autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Riccardo Fusaroli1, Anna Lambrechts2, Dan Bang1,3,4, Dermot M Bowler2, Sebastian B Gaigg2 1. The Interacting Minds Centre, Aarhus University, Jens Christian Skous Vej 4, Building 1483, 8000 Aarhus, DK 2. Autism Research Group, City University London, Northampton Square, London EC1V 0HB 3. Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, Institute of Neurology, University College London, 12 Queen Square, London WC1N 3BG, UK 4. Calleva Research Centre for Evolution and Human Sciences, Magdalen College, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 4AU, United Kingdom RUNNING TITLE: Vocal Production in ASD Number of text pages: 28 Number of tables: 5 Number of figures: 6 Number of Supplementary Materials: 1 Corresponding author: Riccardo Fusaroli, e-mail: [email protected], tel: +45 28890881, address: Jens Christian Skous vej 2, 8000 Aarhus Denmark Grant sponsor: Interacting Minds Center; Grant ID: Clinical Voices. The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/046565; this version posted June 24, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Lay Abstract: Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are reported to speak in distinctive ways. Distinctive vocal production should be better understood as it can affect social interactions and social development and could represent a non- invasive marker for ASD. -

Voice Patterns in Schizophrenia: a Systematic Review and Bayesian Meta-Analysis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/583815; this version posted September 26, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made Running title: VOICE IN availableSCHIZOPHRENIA: under aCC-BY-NC-ND REVIEW 4.0 International AND license META. -ANALYSIS Voice Patterns in Schizophrenia: A systematic Review and Bayesian Meta-Analysis Parola Albertoa, Simonsen Arndisb,c, Bliksted Vibekeb,c, Fusaroli Riccardoc,d a Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Italy b Psychosis Research Unit - Department of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University, Denmark c The Interacting Minds Center - School of Culture and Society, Aarhus University, Denmark d Department of Linguistics, Semiotics and Cognitive Science – School of Communication and Culture, Aarhus University, Denmark Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Alberto Parola, Dipartimento di Psicologia, Via Verdi 10, 10123 Turin (Italy). Phone number: +390116703065 Fax number: +39 0118159039 E-mail: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/583815; this version posted September 26, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 2 VOICE IN SCHIZOPHRENIA: REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS Abstract Voice atypicalities have been a characteristic feature of schizophrenia since its first definitions. They are often associated with core negative symptoms such as flat affect and alogia, and with the social impairments seen in the disorder. -

A Symptom-Based Approach to Treatment of Psychosis in Autism Spectrum Disorder* Victoria Bell†, Henry Dunne†, Tharun Zacharia, Katrina Brooker and Sukhi Shergill

BJPsych Open (2018) 4, 1–4. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2017.2 Short report A symptom-based approach to treatment of psychosis in autism spectrum disorder* Victoria Bell†, Henry Dunne†, Tharun Zacharia, Katrina Brooker and Sukhi Shergill Summary The optimal management of autism with psychosis remains Copyright and usage unclear. This report describes a 22-year-old man with autism and © The Royal College of Psychiatrists 2018. This is an Open Access psychosis who was referred to a tertiary-level specialist psych- article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons osis service, following a 6-year history of deterioration in mental Attribution-NonCommerical-NoDerivatives licence (http://crea- health starting around the time of sitting GCSE examinations and tivecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non- an episode of bullying at school. We describe the individualised commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any symptom-based approach that was effective in his treatment. medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press Declaration of interest must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a The authors declare no conflict of interest. derivative work. Knowledge of both autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and psychosis and investigate the co-occurrence of symptoms.9 The focus on clari- has developed within spectrum constructs. Despite the long history fying the diagnosis may be based on clinician preference or a way of of association between these disorders, there is often little clinician managing complexity, yet this may prove to be an obstacle in the awareness of how to assess and treat psychosis when it coexists with advancement of the formulation and treatment of the difficult ASD.