Benjamin Britten's Spring Symphony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Britten Spring Symphony Welcome Ode • Psalm 150

BRITTEN SPRING SYMPHONY WELCOME ODE • PSALM 150 Elizabeth Gale soprano London Symphony Chorus Alfreda Hodgson contralto Martyn Hill tenor London Symphony Orchestra Southend Boys’ Choir Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Spring Symphony, Op. 44* 44:44 For Soprano, Alto and Tenor solos, Mixed Chorus, Boys’ Choir and Orchestra Part I 1 Introduction. Lento, senza rigore 10:03 2 The Merry Cuckoo. Vivace 1:57 3 Spring, the Sweet Spring. Allegro con slancio 1:47 4 The Driving Boy. Allegro molto 1:58 5 The Morning Star. Molto moderato ma giocoso 3:07 Part II 6 Welcome Maids of Honour. Allegretto rubato 2:38 7 Waters Above. Molto moderato e tranquillo 2:23 8 Out on the Lawn I lie in Bed. Adagio molto tranquillo 6:37 Part III 9 When will my May come. Allegro impetuoso 2:25 10 Fair and Fair. Allegretto grazioso 2:13 11 Sound the Flute. Allegretto molto mosso 1:24 Part IV 12 Finale. Moderato alla valse – Allegro pesante 7:56 3 Welcome Ode, Op. 95† 8:16 13 1 March. Broad and rhythmic (Maestoso) 1:52 14 2 Jig. Quick 1:20 15 3 Roundel. Slower 2:38 16 4 Modulation 0:39 17 5 Canon. Moving on 1:46 18 Psalm 150, Op. 67‡ 5:31 Kurt-Hans Goedicke, LSO timpani Lively March – Lightly – Very lively TT 58:48 4 Elizabeth Gale soprano* Alfreda Hodgson contralto* Martyn Hill tenor* The Southend Boys’ Choir* Michael Crabb director Senior Choirs of the City of London School for Girls† Maggie Donnelly director Senior Choirs of the City of London School† Anthony Gould director Junior Choirs of the City of London School -

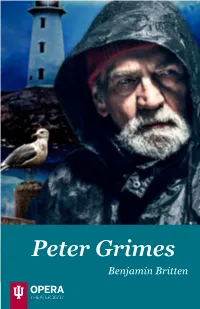

Peter Grimes Benjamin Britten

Peter Grimes Benjamin Britten THEATER 16/17 FOR YOUR INFORMATION Do you want more information about upcoming events at the Jacobs School of Music? There are several ways to learn more about our recitals, concerts, lectures, and more! Events Online Visit our online events calendar at music.indiana.edu/events: an up-to-date and comprehensive listing of Jacobs School of Music performances and other events. Events to Your Inbox Subscribe to our weekly Upcoming Events email and several other electronic communications through music.indiana.edu/publicity. Stay “in the know” about the hundreds of events the Jacobs School of Music offers each year, most of which are free! In the News Visit our website for news releases, links to recent reviews, and articles about the Jacobs School of Music: music.indiana.edu/news. Musical Arts Center The Musical Arts Center (MAC) Box Office is open Monday – Friday, 11:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. Call 812-855-7433 for information and ticket sales. Tickets are also available at the box office three hours before any ticketed performance. In addition, tickets can be ordered online at music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. Entrance: The MAC lobby opens for all events one hour before the performance. The MAC auditorium opens one half hour before each performance. Late Seating: Patrons arriving late will be seated at the discretion of the management. Parking Valid IU Permit Holders access to IU Garages EM-P Permit: Free access to garages at all times. Other permit holders: Free access if entering after 5 p.m. any day of the week. -

Press Information Eno 2013/14 Season

PRESS INFORMATION ENO 2013/14 SEASON 1 #ENGLISHENO1314 NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 CONTENTS Autumn 2013 4 FIDELIO Beethoven 6 DIE FLEDERMAUS Strauss 8 MADAM BUtteRFLY Puccini 10 THE MAGIC FLUte Mozart 12 SATYAGRAHA Glass Spring 2014 14 PeteR GRIMES Britten 18 RIGOLetto Verdi 20 RoDELINDA Handel 22 POWDER HeR FAce Adès Summer 2014 24 THEBANS Anderson 26 COSI FAN TUtte Mozart 28 BenvenUTO CELLINI Berlioz 30 THE PEARL FISHERS Bizet 32 RIveR OF FUNDAMent Barney & Bepler ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 3 FIDELIO NEW PRODUCTION BEETHoven (1770–1827) Opens: 25 September 2013 (7 performances) One of the most sought-after opera and theatre directors of his generation, Calixto Bieito returns to ENO to direct a new production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. Bieito’s continued association with the company shows ENO’s commitment to highly theatrical and new interpretations of core repertoire. Following the success of his Carmen at ENO in 2012, described by The Guardian as ‘a cogent, gripping piece of work’, Bieito’s production of Fidelio comes to the London Coliseum after its 2010 premiere in Munich. Working with designer Rebecca Ringst, Bieito presents a vast Escher-like labyrinth set, symbolising the powerfully claustrophobic nature of the opera. Edward Gardner, ENO’s highly acclaimed Music Director, 2013 Olivier Award-nominee and recipient of an OBE for services to music, conducts an outstanding cast led by Stuart Skelton singing Florestan and Emma Bell as Leonore. Since his definitive performance of Peter Grimes at ENO, Skelton is now recognised as one of the finest heldentenors of his generation, appearing at the world’s major opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and Opéra National de Paris. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

The Four Seasons I

27 Season 2013-2014 Friday, November 29, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, November 30, at 8:00 Sunday, December 1, at 2:00 Richard Egarr Conductor and Harpsichord Giuliano Carmignola Violin Vivaldi The Four Seasons I. Spring, Concerto in E major, RV 269 a. Allegro b. Largo c. Allegro II. Summer, Concerto in G minor, RV 315 a. Allegro non molto b. Adagio alternating with Presto c. Presto III. Autumn, Concerto in F major, RV 293 a. Allegro b. Adagio molto c. Allegro IV. Winter, Concerto in F minor, RV 297 a. Allegro non molto b. Largo c. Allegro Intermission 28 Purcell Suite No. 1 from The Fairy Queen I. Prelude II. Rondeau III. Jig IV. Hornpipe V. Dance for the Fairies Haydn Symphony No. 101 in D major (“The Clock”) I. Adagio—Presto II. Andante III. Menuetto (Allegretto)—Trio—Menuetto da capo IV. Vivace This program runs approximately 1 hour, 40 minutes. The November 29 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 3 Story Title 29 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra community itself. His concerts to perform in China, in 1973 is one of the preeminent of diverse repertoire attract at the request of President orchestras in the world, sold-out houses, and he has Nixon, today The Philadelphia renowned for its distinctive established a regular forum Orchestra boasts a new sound, desired for its for connecting with concert- partnership with the National keen ability to capture the goers through Post-Concert Centre for the Performing hearts and imaginations of Conversations. -

That to See How Britten Handles the Dramatic and Musical Materials In

BOOKS 131 that to see how Britten handles the dramatic and musical materials in the op- era is "to discover anew how from private pain the great artist can fashion some- thing that transcends his own individual experience and touches all humanity." Given the audience to which it is directed, the book succeeds superbly. Much of it is challenging and stimulating intellectually, while avoiding exces- sive weightiness, and at the same time, it is entertaining in the very best sense of the word. Its format being what it is, there are inevitable duplications of information, and I personally found the Garbutt and Garvie articles less com- pelling than the remainder of the book. The last two articles of Brett's, excel- lent as they are, also tend to be a little discursive, but these are minor reserva- tions. For anyone who cares for this masterwork of twentieth-century opera, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/4/3/131/1587210 by guest on 01 October 2021 or for Britten and his music, this book is obligatory reading. Carlisle Floyd Peter Grimes/Gloriana Benjamin Britten English National Opera/Royal Opera Guide 24 Nicholas John, series editor London: John Calder; New York: Riverrun Press, 1983 128 pages, $5.95 (paper) The English National Opera/Royal Opera Guides, small paperbacks with siz- able contents, are among the best introductions available to the thirty-plus operas published in the series so far. Each guide includes some essays by ac- knowledged authorities on various aspects of its subject, followed by a table of major musical themes, a complete libretto (original language plus transla- tion), a brief bibliography, and a discography. -

Proquest Dissertations

Benjamin Britten's Nocturnal, Op. 70 for guitar: A novel approach to program music and variation structure Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alcaraz, Roberto Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 13:06:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279989 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be f^ any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitlsd. Brolcen or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkl not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectk)ning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additkxial charge. -

The Magic Flute Programme

Programme Notes September 4th, Market Place Theatre, Armagh September 6th, Strule Arts Centre, Omagh September 10th & 11th, Lyric Theatre, Belfast September 13th, Millennium Forum, Derry-Londonderry 1 Welcome to this evening’s performance Brendan Collins, Richard Shaffrey, Sinéad of The Magic Flute in association with O’Kelly, Sarah Richmond, Laura Murphy Nevill Holt Opera - our first ever Mozart and Lynsey Curtin - as well as an all-Irish production, and one of the most popular chorus. The showcasing and development operas ever written. of local talent is of paramount importance Open to the world since 1830 to us, and we are enormously grateful for The Magic Flute is the first production of the support of the Arts Council of Northern Austins Department Store, our 2014-15 season to be performed Ireland which allows us to continue this The Diamond, in Northern Ireland. As with previous important work. The well-publicised Derry / Londonderry, seasons we have tried to put together financial pressures on arts organisations in Northern Ireland an interesting mix of operas ranging Northern Ireland show no sign of abating BT48 6HR from the 18th century to the 21st, and however, and the importance of individual combining the very well known with the philanthropic support and corporate Tel: +44 (0)28 7126 1817 less frequently performed. Later this year sponsorship has never been greater. I our co-production (with Opera Theatre would encourage everyone who enjoys www.austinsstore.com Company) of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore seeing regular opera in Northern Ireland will tour the Republic of Ireland, following staged with flair and using the best local its successful tour of Northern Ireland operatic talent to consider supporting us last year. -

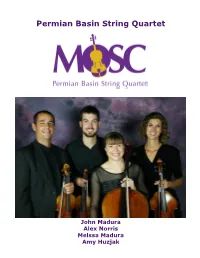

Permian Basin String Quartet

Permian Basin String Quartet John Madura Alex Norris Melssa Madura Amy Huzjak Described by the Odessa American as “a precise and authoritative sound” the Permian Basin String Quartet (PBSQ) is the resident quartet of the Midland-Odessa Symphony & Chorale and is comprised of the principal string players of the orchestra. The quartet members have developed a loyal audience and a reputation as a leading ensemble in the Permian Basin. The PBSQ has made recent appearances in Midland, Odessa, Abilene, Alpine, San Angelo, Big Spring, Lubbock, and Hobbs, NM. In 2015, the PBSQ was the featured guest artist on the Abilene Christian University (ACU) Tour as the soloists on Short Stories by Joel Puckett as well as gave the Texas premiers of several works by ACU visiting composer Hyunjoo Lee. In 2013 the PBSQ appeared in the Abilene Philharmonic Nocturne series as well as the Church of the Heavenly Rest Chamber series. The PBSQ frequently appears with the San Angelo State University Choir, has given masterclasses in Mexico and Lubbock, TX as well as appeared with Chamber Music Amarillo. In addition to performance, the PBSQ is very dedicated to music education. The PBSQ gives educational concerts at elementary schools in the Permian Basin throughout the year. In addition, the PBSQ serves as section coaches for several high school orchestras in the Permian Basin as well as the University of Texas-Permian Basin (UTPB) University Orchestra. The PBSQ has also partnered with UTPB as the faculty for the All-Region Summer Workshop as well as the Hartwick College Summer Festival in Oneonta, NY. -

Adventures Adventures

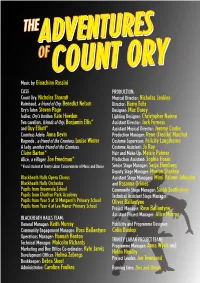

THEADVENTURESADVENTURES COUNTCOUNT ORYORY Music by Gioachino Rossini CAST: PRODUCTION: Count Ory: Nicholas Sharratt Musical Director: Nicholas Jenkins Raimbaud, a friend of Ory: Benedict Nelson Director: Harry Fehr Ory’s Tutor: Steven Page Designer: Max Dorey Isolier, Ory’s brother: Kate Howden Lighting Designer: Christopher Nairne Two cavaliers, friends of Ory: Benjamin Ellis* Assistant Director: Jack Furness and Guy Elliott* Assistant Musical Director: Jeremy Cooke Countess Adele: Anna Devin Production Manager: Rene (Freddy) Marchal Ragonde , a friend of the Countess: Louise Winter Costume Supervisor: Felicity Langthorne A lady, another friend of the Countess: Costume Assistant: Jo Ray Claire Barton* Hair and Make-Up: Maisie Palmer Alice, a villager: Zoe Freedman* Production Assistant: Sophie Horan *Vocal student at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance Senior Stage Manager: Sasja Ekenberg Deputy Stage Manager: Marian Sharkey Blackheath Halls Opera Chorus Assistant Stage Managers: Mimi Palmer-Johnston Blackheath Halls Orchestra and Rosanna Grimes Pupils from Greenvale School Community Stage Manager: Sarah Southerton Pupils from Charlton Park Academy Technical Assistant Stage Manager: Pupils from Year 5 at St Margaret’s Primary School Oliver Ballantyne Pupils from Year 4 at Lee Manor Primary School Project Manager: Rose Ballantyne Assistant Project Manager: Alice Murray BLACKHEATH HALLS TEAM: General Manager: Keith Murray Publicity and Programme Designer: Community Engagement Manager: Rose Ballantyne Colin Dunlop Operations Manager: Hannah Benton TRINITY LABAN PROJECT TEAM: Technical Manager: Malcolm Richards Programme Manager: Anna Wyatt and Marketing and Box Office Co-ordinator:Kyle Jarvis Helen Hendry Development Officer:Helma Zebregs Project Leader: Joe Townsend Bookkeeper: Debra Skeet Administrator: Caroline Foulkes Running time: 2hrs and 30mins We have been staging community operas at Blackheath WELCOME Halls since July 2007. -

Edward Grint Bass-Baritone

Edward Grint Bass-Baritone British bass-baritone Edward Grint studied at King’s College, Cambridge as a choral scholar, and at the International Benjamin Britten Opera School at the Royal College of Music. He has become sought after particularly as a performer of the baroque repertoire and engagements this season and next include appearances with Les Arts Florissants, Les Musiciens du Louvre, the Early Opera Company, La Nuova Musica and the Irish Baroque Orchestra. He is a prizewinner of the International Singing Competition for Baroque Opera, Pietro Antonio Cesti in Innsbruck, the London Handel Competition and won the Clermont Ferrand competition in France. On the operatic stage, Edward’s roles include POLYPHEMUS Acis and Galatea Opera Avignon, ARCAS Iphigenie en Aulide Theater an der Wien, ADONIS Venus and Adonis, AENEAS Dido and Aeneas Innsbruck Festival, FATHER AKITA in Neige by Catherine Kontz Grand Theatre Luxembourg and TEOBALDO Faramondo by Handel Göttingen Handel Festival. At the Royal College of Music, Edward performed COUNT ALMAVIVA Le Nozze di Figaro, SPLENDIANO Djamileh, MR DELANCEY Aqualung (World Premiere), as well as GARIBALDO Rodelinda, TIRENIO Il Pastor Fido and ISACIO Riccardo Primo London Handel Festival. Other roles performed include COLONEL Patience Musée D’Orsay, Paris, HOBSON Peter Grimes, MOTHER Die Sieben Tödsunden Cuenca Festival, THOAS Iphigenie en Tauride Euphonia, ZARETSKY Eugene Onegin Ryedale Festival, GUGLIELMO Cosi fan tutte for the Rye Festival, ACHILLA Giulio Cesare in Amsterdam and POLYPHEMUS Acis and Galatea with Laurence Cummings in London. In concert Edward has performed with many of the UK’s leading ensembles. Highlights include Bach and Kuhnau Cantatas with The King’s Consort Wigmore Hall, Bach St.