Performing Remediation: the Minstrel, the Camera, and the Octoroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile Season 19-20 Media Release

2019-20: GENERATIONS Brenden Jacobs-Jenkins/ Lynn Nottage/ Paula Vogel FOR IMMEDIATE MEDIA RELEASE: Profile Theatre Press Contact: Jen Mitas, Marketing Consultant [email protected] 503-804-2402 Profile Theatre’s 2019-20 Season Celebrates the Voices and Visions of Three Playwrights Across Generations Lynn Nottage, Paula Vogel and Brenden Jacobs-Jenkins PORTLAND, OREGON. May 20, 2019- PROFILE THEATRE’S next season will fea- ture three of America’s most widely celebrated contemporary playwrights: Branden Jacobs-Jenkins (b. 1984), Lynn Nottage (b. 1964), and Paula Vogel (b. 1951). Profile Theatre is one of only three theaters in the country to dedicate their season to an in-depth exploration of a playwright’s vision, using that unique vision as a lens to broaden perspectives on our shared world. Now, in an innovation that deploys Pro- file’s mission to unique effect, we present Generations: two seasons of plays from three of America’s most beloved playwrights whose plays dramatize life, labor and death in the United States and beyond from three different generational vantage points. These visionaries are all connected through the prizes and programs that have shaped them. A gifted playwright, Vogel mentored a generation of playwrights, including Lynn Nottage, who studied with Vogel at Brown. Jacobs-Jenkins was the Paula Vogel Playwright-in-Residence at the Vineyard Theatre, and was on the Su- san Smith Blackburn committee that awarded the prize to Nottage for Sweat. All Pulitzer Prize nominated (or winning), all heralded for the beauty of their writing, their innovative theatricality and deep humanity, Vogel, Nottage and Jacobs-Jenkins’ work stands as a testament to the brilliance of American theatre. -

The Champ Readies for Belmont Breeders= Cup

TUESDAY, JUNE 2, 2015 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here THE CHAMP READIES FOR BELMONT GLENEAGLES, FOUND TO BYPASS EPSOM GI Kentucky Derby and GI Preakness S. winner The Coolmore partners= dual Guineas winner American Pharoah (Pioneerof the Nile) registered his last Gleneagles (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) and Group 1-winning filly serious work before Saturday=s GI Belmont S. under Found (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) are no longer under cloudy skies Monday at consideration for Saturday=s Churchill Downs. The bay G1 Epsom Derby, and both covered five panels in will target mile races at 1:00.20 (video) with Royal Ascot. Martin Garcia in the irons Gleneagles was removed shortly after the from the Classic at renovation break. Monday=s scratching stage Churchill clocker John and will head to the G1 St. Nichols recorded 1/8-mile James=s Palace S. on the opening day of the Royal fractions in :13, :25 meeting June 16. Found, (:12), :36.60 (11.60) and who has been second in :48.60 (:12). He galloped Gleneagles winning the Irish both starts this year out six furlongs in 1:13, 2000 Guineas including the G1 Irish 1000 seven-eighths in 1:26 and Racing Post Photo Guineas May 24, will a mile in 1:39.60. contest the G1 Coronation Baffert noted how S. June 19. Found would have had to be supplemented pleased he was with the to the Derby at a cost of ,75,000. Coolmore and American Pharoah work later in the morning. trainer Aidan O=Brien are expected to be represented in Horsephotos AEverything went really the Derby by G3 Chester Vase scorer Hans Holbein well today,@ Hall of Fame (GB) (Montjeu {Ire}), owned in partnership with Teo Ah trainer Bob Baffert said outside Barn 33. -

Replaying and Rediscovering the Octoroon

Article Replaying and Rediscovering The Octoroon Merrill, Lisa and Saxon, Theresa Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/17558/ Merrill, Lisa and Saxon, Theresa ORCID: 0000-0002-2129-2570 (2017) Replaying and Rediscovering The Octoroon. Theatre Journal, 69 (2). ISSN 0192-2882 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/tj.2017.0021 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk 1 Replaying and Rediscovering The Octoroon Lisa Merrill and Theresa Saxon "[W]hen one is considering the crimes of slavery, the popular theater is as central as the courthouse."1 Saidiya Hartman For over one hundred and fifty years, productions and adaptations of Irish playwright Dion Boucicault's explosive 1859 melodrama, The Octoroon, have reflected differing and sometimes contentious meanings and messages about race and enslavement in a range of geographic locations and historical moments. In this melodrama, set on a plantation in Louisiana, audiences witness the drama of Zoe Peyton, a mixed-race white-appearing heroine who learns after the sudden death of her owner/father, that she is relegated to the condition of "chattel property" belonging to the estate, since she was born of a mother who had herself been enslaved.2 Rather than submit to a new master, having been sold at auction, Zoe poisons herself and dies, graphically, on stage. -

NL-Spring-2020-For-Web.Pdf

RANCHO SAN ANTONIO Boys Home, Inc. 21000 Plummer Street, Chatsworth, CA 91311 (818) 882-6400 Volume 38 No. 1 www.ranchosanantonio.org Spring 2020 God puts rainbows in the clouds so that each of us - in the dreariest and most dreaded moments - can see a possibility of hope. -Maya Angelou A REFLECTION FROM BROTHER JOHN CONNECTING WITH OUR COMMUNITY I would like to share with you a letter from a parent: outh develop a sense of identity and value “Dear All of You at Rancho, Ythrough culture and connections. To increase cultural awareness and With the simplicity of a child, and heart full of sensitivity within our gratitude and appreciation of a parent…I thank Rancho community, each one of you, for your concern and giving of Black History Month yourselves in trying to make one more life a little was celebrated in Febru- happier… ary with a fun and edu- I know they weren’t all happy days nor easy days… cational scavenger hunt some were heartbreaking days… “give up” days… that incorporated impor- so to each of you, thank you. For you to know even tant historical facts. For entertainment, one of our one life has breathed easier because you lived, this very talented staff, a professional saxophone player, is to have succeeded. and his bandmates played Jazz music for our youth Your lives may never touch my son’s again, but I during our celebratory dinner. have faith your labor has not been in vain. And to each one of you young men, I shall pray, with ACTIVITIES DEPARTMENT UPDATE each new life that comes your way… may wisdom guide your tongue as you soothe the hearts of to- ancho’s Activities Department developed a morrow’s men. -

“Brownsville Song (B-Side for Tray)” a New Play by KIMBER LEE Directed by PATRICIA Mcgregor

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER CASTING ANNOUNCEMENT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE SHELDON BEST, SUN MEE CHOMET, LIZAN MITCHELL, CHRIS MYERS, TALIYAH WHITAKER TO BE FEATURED IN THE LCT3/LINCOLN CENTER THEATER NEW YORK PREMIERE PRODUCTION OF “brownsville song (b-side for tray)” A new play by KIMBER LEE Directed by PATRICIA McGREGOR 6 WEEKS ONLY! SATURDAY, OCTOBER 4 THROUGH SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 16 OPENING NIGHT, MONDAY, OCTOBER 20 AT THE CLAIRE TOW THEATER Sheldon Best, Sun Mee Chomet, Lizan Mitchell, Chris Myers and Taliyah Whitaker will comprise the cast of the upcoming LCT3/Lincoln Center Theater New York premiere production of brownsville song (b-side for tray), a new play by Kimber Lee. The production, to be directed by Patricia McGregor, will begin performances Saturday, October 4, running for six weeks only through Sunday, November 16 at the Claire Tow Theater (150 West 65 Street). Opening night is Monday, October 20. brownsville song (b-side for tray) moves fluidly through time as the family of Tray (Sheldon Best), a spirited 18 year-old whose life is cut short, navigate their grief and find hope together. Playwright KIMBER LEE’s plays include fight and tokyo fish story. Center Theatre Group recently presented the world premiere of her play different words for the same thing in Los Angeles at the Kirk Douglas Theatre. Lee’s work has also been presented by the Lark Play Development Center, Page 73, Hedgebrook, Seven Devils, the Bay Area Playwrights Festival, REPRESENT!, Playwrights Festival ACT/Seattle, Great Plains Theatre Conference, Southern Rep and Mo`olelo. Lee’s play fight received the 2010 Holland New Voices Award, and she has been a Lark Playwrights’ Workshop Fellow, a Dramatists Guild Fellow, and a Core Apprentice at The Playwrights’ Center. -

"I's Not So Wicked As I Use to Was:" the Interplay of Race and Dignity In

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons HON499 projects Honors Program Spring 2018 "I's Not So Wicked as I Use to Was:" The nI terplay of Race and Dignity in Nineteenth-Century American Drama and Blackface Minstrelsy Sam Volosky [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects Part of the Acting Commons, African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Volosky, Sam, ""I's Not So Wicked as I Use to Was:" The nI terplay of Race and Dignity in Nineteenth-Century American Drama and Blackface Minstrelsy" (2018). HON499 projects. 16. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects/16 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in HON499 projects by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “I’s Not So Wicked as I Use to Was:” The Interplay of Race and Dignity in Nineteenth-Century American Drama and Blackface Minstrelsy By Sam Volosky At the origin of theatrical performance, theatre was used by the ancient Greeks as an efficacious tool to enact social change within their communities. Playwrights used tragedy and comedy in order to sway their audiences so that they might vote in one direction or the other on matters such as war, government, and social structure. -

An Octoroon by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins

AN OCTOROON BY BRANDEN JACOBS-JENKINS DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. AN OCTOROON.indd 1 1/26/2015 3:15:39 PM AN OCTOROON Copyright © 2015, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of AN OCTOROON is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for AN OCTOROON are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. -

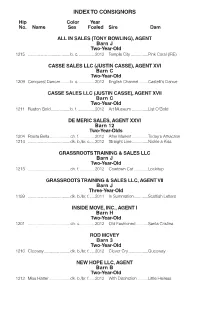

INDEX to CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam ALL IN SALES (TONY BOWLING), AGENT Barn J Two-Year-Old 1215 ................................. ......b. c. ...............2012 Temple City ................Pink Coral (IRE) CASSE SALES LLC (JUSTIN CASSE), AGENT XVI Barn C Two-Year-Old 1209 Conquest Dancer .........b. c. ...............2012 English Channel ........Castelli's Dance CASSE SALES LLC (JUSTIN CASSE), AGENT XVII Barn C Two-Year-Old 1211 Ruston Gold ..................b. f. ................2012 Art Museum ...............List O'Gold DE MERIC SALES, AGENT XXVI Barn 12 Two-Year-Olds 1204 Rosita Bella ...................ch. f. ..............2012 After Market ...............Today's Attraction 1214 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ....2012 Straight Line ...............Nickle a Kiss GRASSROOTS TRAINING & SALES LLC Barn J Two-Year-Old 1213 ................................. ......ch. f. ..............2012 Cowtown Cat .............Lockitup GRASSROOTS TRAINING & SALES LLC, AGENT VII Barn J Three-Year-Old 1199 ................................. ......dk. b./br. f. .....2011 In Summation .............Scottish Letters INSIDE MOVE, INC., AGENT I Barn H Two-Year-Old 1201 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2012 Old Fashioned ...........Santa Cristina ROD MCVEY Barn 3 Two-Year-Old 1216 Cleeway ........................dk. b./br. f. .....2012 Clever Cry ..................Queeway NEW HOPE LLC, AGENT Barn B Two-Year-Old 1212 Miss Hatter ....................dk. b./br. f. .....2012 With Distinction -

By Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Ph.D. Professor of History Norfolk State University

By Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Ph.D. Professor of History Norfolk State University American Beacon April 24, 1834 American Beacon April 26, 1834 Southern Argus January 10, 1859 Southern Argus, January 24, 1855 Southern Argus, January 15, 1859 Southern Argus January 17, 1859 Southern Argus January 10, 1859 Southern Argus September 15, 1859 Southern Argus, January 17, 1855 Southern Argus March 7, 1855 Southern Argus January 13, 1855 Slavery was prosperous and economically important to the U.S., especially after the invention of the cotton gin In 1860 the South produced 7/8ths of the world's cotton. Cotton represented 57.5% of the value of all U.S. exports. 55% of enslaved people in the United States were employed in cotton production. Cotton Production in the South, 1820–1860 Cotton production expanded westward between 1820 and 1860 into Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, and western Tennessee. Source: Sam Bowers Hilliard, Atlas of Antebellum Southern Agriculture (Louisiana State University Press, 1984) pp. 67–71. Ownership of Enslaved people in the South was unevenly distributed 25% of white families owned slaves in 1860 Fell from 36% in 1830 Nearly half of slaveholders owned fewer than five 12% owned more than twenty slaves 1% owned more than fifty slaves Typical slave lived on a sizeable plantation As Pro-Slavery supporters continued to use the law to protect their “property,” Abolitionists employed all manner of strategies to persuade the American public and its leadership to end slavery. One of their first strategies was to unite groups of like- minded individuals to fight as a body. -

IMPINGE (NZ) 49 Bay Mare (Branded Nr Sh

Barn J Stables 29-36, 45-52, 61-64 On Account of EDINGLASSIE STUD, Muswellbrook (As Agent) Lot 600 IMPINGE (NZ) 49 Bay mare (Branded nr sh. off sh.) Foaled 2001 1 Nijinsky ...........................by Northern Dancer ... Caerleon ......................... SIRE Foreseer .................... by Round Table ........... GENEROUS (IRE) ..... Master Derby ............. by Dust Commander .... Doff the Derby ............... Margarethen .............. by Tulyar .................... Storm Bird .................. by Northern Dancer ... DAM Bluebird (USA) ................ Ivory Dawn ................ by Sir Ivor ................... IMCO RESOURCE (IRE) Saratoga Six ............... by Alydar .................... 1996 Sasimoto ....................... Mobcap ...................... by Tom Rolfe .............. GENEROUS (IRE) (1988). 5 wins, Ascot King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Diamond S., Gr.1. Sire of 995 rnrs, 652 wnrs, 45 SW, inc. SW Catella, etc. Sire of the dams of SW Gingernuts, Lion Tamer, Golan, Survived, Nahrain, Mourinho, We Can Say it Now, Proportional, Al Shemali, Mackintosh, Dandino, No Evidence Needed, Armure, Tartan Bearer, Essential Edge, Tungsten Strike, High Accolade, Black Moon, Vote Often, etc. 1st Dam IMCO RESOURCE (IRE), by Bluebird (USA). 2 wins at 2 at 1600m, Rome Premio Disco Rosso. Dam of 8 named foals, all raced, 5 winners, inc:- THAT'S NOT IT (g by Foreplay). 2 wins at 1100m, 1200m, $209,540, MVRC Red Anchor S., Gr 3, 2d VRC Moomba P., L. Impinge (f by Generous (Ire)). 3 wins. See below. 2nd Dam SASIMOTO, by Saratoga Six. 5 wins–3 at 2–1000m to 1400m, Milan Criterium Nazionale, L, Rome Premio Aniene, L, 3d Rome Criterium Femminile, L. Half- sister to NOTEBOOK. Dam of 11 foals, 8 to race, 7 winners, inc:- Blue Shift. 8 wins 1000m to 1408m, Rome Premio Nipissing. -

The "Tragic Octoroon" in Pre-Civil War Fiction

JULES ZANGER SouthernIllinois University,Edwardsville Campus The "Tragic Octoroon" In Pre-Civil War Fiction ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT CHARACTERS OF PRE-CIVIL WAR ABOLITIONIST fictionwas the "tragicoctoroon." Presented first in the earliestantislavery novel, The Slave (1836), the characterappeared in more than a dozen other works.' By the time the most importantof these works-Uncle Tom's Cabin and The Octoroon-were written,the characterhad ac- quired certain stereotypicqualities and had come to appear in certain stereotypicsituations. Brieflysummarized, the "tragicoctoroon" is a beautifulyoung girl who possessesonly the slightestevidences of Negro blood, who speaks with no trace of dialect, who was raised and educated as a white child and as a lady in the household of her father,and who on her paternal side is descendedfrom "some of the best blood in the 'Old Dominion.'" In her sensibilityand her vulnerabilityshe resembles,of course, the conven- tional ingenue "victim" of sentimentalromance. Her condition is radi- callychanged when, at her father'sunexpected death, it is revealed thathe has failed to free her properly.She discoversthat she is a slave; her person is attachedas propertyby her father'screditors. Sold into slavery, she is victimized,usually by a lower-class,dialect-speaking slave dealer or overseer-often,especially after the Fugitive Slave Act, a Yankee- who attemptsto violate her; she is loved by a high-bornyoung Northerner 1 Among the most readily available of these works are R. Hildreth, The Slave (1836); J. H. Ingraham, Quadroone (1840); H. W. Longfellow, The Quadroon Girl (1842); Mrs. E.D.E.N. Southworth, Retribution (1840); E.C. Pierson, Cousin Franck's Household (1842); H. -

How Mixed-Race Americans Navigated the Racial Codes of Antebellum America

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses, 2020-current The Graduate School 5-7-2020 Under cover of lightness: How mixed-race Americans navigated the racial codes of Antebellum America Alexander Brooks Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029 Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Brooks, Alexander, "Under cover of lightness: How mixed-race Americans navigated the racial codes of Antebellum America" (2020). Masters Theses, 2020-current. 48. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029/48 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Under Cover of Lightness: How Mixed-Race Americans Navigated the Racial Codes of Antebellum America Alex Brooks A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2020 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Rebecca Brannon Committee Members/ Readers: Gabrielle Lanier David Owusu-Ansah Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Miscegenation 3. North 4. Upper South 5. Lower South 6. 1850s Turbulence 7. Liberia 8. Conclusion ii Abstract This thesis investigates the way people of mixed “racial” ancestry—known as mulattoes in the 18th and 19th centuries—navigated life in deeply racially divided society. Even understanding “mulatto strategies” is difficult because it is to study a group shrouded in historical ambiguity by choice.