Digitalcommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

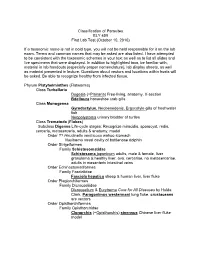

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Anti-Trichinella Antibodies in Breeding Pigs Farmed Under Controlled

Pozio et al. Parasites Vectors (2021) 14:417 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04920-1 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Animal welfare and zoonosis risk: anti-Trichinella antibodies in breeding pigs farmed under controlled housing conditions Edoardo Pozio1, Mario Celli2, Alessandra Ludovisi1, Maria Interisano1, Marco Amati1 and Maria Angeles Gómez‑Morales1* Abstract Background: Domesticated pigs are the main source of Trichinella sp. infections for humans, particularly when reared in backyards or free‑ranging. In temperate areas of southern Europe, most pigs are farmed under controlled housing conditions, but sows and sometimes fattening pigs have access to outdoors to improve animal welfare. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether outdoor access of breeding pigs farmed under controlled housing conditions can represent a risk for Trichinella sp. transmission when the farm is located in an agricultural area interspersed with wooded areas and badlands, where Trichinella spp. could be present in wildlife. Methods: Serum samples were collected from 63 breeding sows and one boar before and after their access to an open fenced area for 2 months and from 84 pigs that never had outdoor access. Samples were screened for anti‑Trich- inella antibodies by ELISA, and positive sera were confrmed using Western blot (Wb) excretory/secretory antigens. To detect Trichinella sp. larvae, muscle tissues from serologically positive and negative pigs were tested by artifcial digestion. Results: Thirteen (20.6%) sows and one boar tested positive with both ELISA and Wb. No larvae were detected in muscle samples of serologically positive and serologically negative pigs. Positive serum samples were then tested by Wb using crude worm extract as antigens. -

New Aspects of Human Trichinellosis: the Impact of New Trichinella Species F Bruschi, K D Murrell

15 REVIEW Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.78.915.15 on 1 January 2002. Downloaded from New aspects of human trichinellosis: the impact of new Trichinella species F Bruschi, K D Murrell ............................................................................................................................. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:15–22 Trichinellosis is a re-emerging zoonosis and more on anti-inflammatory drugs and antihelminthics clinical awareness is needed. In particular, the such as mebendazole and albendazole; the use of these drugs is now aided by greater clinical description of new Trichinella species such as T papuae experience with trichinellosis associated with the and T murrelli and the occurrence of human cases increased number of outbreaks. caused by T pseudospiralis, until very recently thought to The description of new Trichinella species, such as T murrelli and T papuae, as well as the occur only in animals, requires changes in our handling occurrence of outbreaks caused by species not of clinical trichinellosis, because existing knowledge is previously recognised as infective for humans, based mostly on cases due to classical T spiralis such as T pseudospiralis, now render the clinical picture of trichinellosis potentially more compli- infection. The aim of the present review is to integrate cated. Clinicians and particularly infectious dis- the experiences derived from different outbreaks around ease specialists should consider the issues dis- the world, caused by different Trichinella species, in cussed in this review when making a diagnosis and choosing treatment. order to provide a more comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment. SYSTEMATICS .......................................................................... Trichinellosis results from infection by a parasitic nematode belonging to the genus trichinella. -

Trichinella Nativa in a Black Bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2005 Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire D.E. Hill Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory, [email protected] H.R. Gamble National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.S. Zarlenga Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory & Bovine Functions and Genomics Laboratory C. Cross Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory J. Finnigan New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories, Concord Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Hill, D.E.; Gamble, H.R.; Zarlenga, D.S.; Cross, C.; and Finnigan, J., "Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire" (2005). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 2244. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/2244 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Veterinary Parasitology 132 (2005) 143–146 www.elsevier.com/locate/vetpar Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire D.E. Hill a,*, H.R. Gamble c, D.S. Zarlenga a,b, C. Coss a, J. Finnigan d a United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Animal and Natural Resources Institute, Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory, Building 1044, BARC-East, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA b Bovine Functions and Genomics Laboratory, Building 1044, BARC-East, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA c National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, USA d The Food Safety Microbiology Unit, New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories, Concord, NH, USA Abstract A suspected case of trichinellosis was identified in a single patient by the New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories in Concord, NH. -

Trichinella Britovi

Pozio et al. Parasites Vectors (2020) 13:520 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04394-7 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Diferences in larval survival and IgG response patterns in long-lasting infections by Trichinella spiralis, Trichinella britovi and Trichinella pseudospiralis in pigs Edoardo Pozio1, Giuseppe Merialdi2, Elio Licata3, Giacinto Della Casa4, Massimo Fabiani1, Marco Amati1, Simona Cherchi1, Mattia Ramini2, Valerio Faeti4, Maria Interisano1, Alessandra Ludovisi1, Gianluca Rugna2, Gianluca Marucci1, Daniele Tonanzi1 and Maria Angeles Gómez‑Morales1* Abstract Background: Domesticated and wild swine play an important role as reservoir hosts of Trichinella spp. and a source of infection for humans. Little is known about the survival of Trichinella larvae in muscles and the duration of anti‑ Trichinella antibodies in pigs with long‑lasting infections. Methods: Sixty pigs were divided into three groups of 20 animals and infected with 10,000 larvae of Trichinella spiralis, Trichinella britovi or Trichinella pseudospiralis. Four pigs from each group were sacrifced at 2, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months post‑infection (p.i.) and the number of larvae per gram (LPG) of muscles was calculated. Serum samples were tested by ELISA and western blot using excretory/secretory (ES) and crude antigens. Results: Trichinella spiralis showed the highest infectivity and immunogenicity in pigs and larvae survived in pig mus‑ cles for up to 2 years p.i. In these pigs, the IgG level signifcantly increased at 30 days p.i. and reached a peak at about 60 days p.i., remaining stable until the end of the experiment. In T. britovi-infected pigs, LPG was about 70 times lower than for T. -

Morphology, Life Cycle, Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella Spiralis

Paper No. : 08 Biology of Parasitism Module : 26 Morphology, Life Cycle, Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Neeta Sehgal Head, Department of Zoology, University of Delhi Paper Coordinator: Dr. Pawan Malhotra ICGEB, New Delhi Content Writer: Dr. Rita Rath Dyal Singh College, University of Delhi Content Reviewer: Prof. Virender Kumar Bhasin Department of Zoology, University of Delhi 1 Biology of Parasitism ZOOLOGY Morphology, Life Cycle and Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella Description of Module Subject Name ZOOLOGY Paper Name Biology of Parasitism- ZOOL OO8 Module Name/Title Morphology, Life Cycle, Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella Module Id 26; Morphology, Life Cycle, Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis Keywords Trichinosis, pork worm, encysted larva, striated muscle , intestinal parasite Contents 1. Learning Outcomes 2. History 3. Geographical Distribution 4. Habit and Habitat 5. Morphology 5.1. Adult 5.2. Larva 6. Life Cycle 7. Pathogenicity 7.1. Diagnosis 7.2. Treatment 7.3. Prophylaxis 8. Phylogenetic Position 9. Genomics 10. Proteomics 11. Summary 2 Biology of Parasitism ZOOLOGY Morphology, Life Cycle and Pathogenicity and Prophylaxis of Trichinella 1. Learning Outcomes This unit will help to: Understand the medical importance of Trichinella spiralis. Identify the male and female worm from its morphological characteristics. Explain the importance of hosts in the life cycle of Trichinella spiralis. Diagnose the symptoms of the disease caused by the parasite. Understand the genomics and proteomics of the parasite to be able to design more accurate diagnostic, preventive, curative measures. Suggest various methods for the prevention and control of the parasite. Trichinella spiralis (Pork worm) Classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Nematoda Class: Adenophorea Order: Trichocephalida Superfamily: Trichinelloidea Genus: Trichinella Species: spiralis 2. -

Trichinellosis Outbreak Due to Wild Boar Meat Consumption in Southern

Turiac et al. Parasites & Vectors (2017) 10:107 DOI 10.1186/s13071-017-2052-5 LETTERTOTHEEDITOR Open Access Trichinellosis outbreak due to wild boar meat consumption in southern Italy Iulia Adelina Turiac1,2, Maria Giovanna Cappelli2, Rita Olivieri3, Raffaele Angelillis3, Domenico Martinelli2, Rosa Prato2* and Francesca Fortunato2 Abstract We report a Trichinella britovi outbreak investigated during February-March 2016 in southern Italy. The source of infection was meat from infected wild boars that were illegally hunted and, hence, not submitted to post-mortem veterinary inspection. Thirty persons reported having eaten raw dried homemade sausages; five cases of trichinellosis were confirmed. Wild game meat consumers need to be educated about the risk for trichinellosis. Keywords: Trichinella britovi, Trichinellosis, Italy, Wild boar meat, Zoonosis Letter to the Editor presence of Trichinella, as per the EU legislation, and con- In the European countries, the wildlife and domestic sumed as raw dried homemade sausages. reservoirs of Trichinella spp. still pose a risk for humans, A 36 year-old hunter was admitted to the “Casa Sollievo leading to outbreaks. Wild carnivore mammals are of della Sofferenza” Hospital, San Giovanni Rotondo city particular importance since a large number of hunted on 25 January 2016, suffering from fever (temperature animals escape veterinary control [1]. According to the 40–41 °C), myalgia, facial and periorbital swelling, epidemiological data the European Centre for Disease diarrhoea, vomiting, abdominal pain and night sweating. Prevention and Control (ECDC), trichinellosis is most These symptoms were developed 20 days before hospi- prevalent in eastern Europe but also in Italy and Spain talisation. Laboratory analysis showed marked eosinophilia where outbreaks were reported in the past 10 years [2]. -

Comparative Genomics of the Major Parasitic Worms

Comparative genomics of the major parasitic worms International Helminth Genomes Consortium Supplementary Information Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 Contributions from Consortium members ..................................................................................... 5 Methods .................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Sample collection and preparation ................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Data production, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (WTSI) ........................................................................ 12 DNA template preparation and sequencing................................................................................................. 12 Genome assembly ........................................................................................................................................ 13 Assembly QC ................................................................................................................................................. 14 Gene prediction ............................................................................................................................................ 15 Contamination screening ............................................................................................................................ -

Trichinellosis Surveillance — United States, 2002–2007

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report www.cdc.gov/mmwr Surveillance Summaries December 4, 2009 / Vol. 58 / No. SS-9 Trichinellosis Surveillance — United States, 2002–2007 Department Of Health And Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR CONTENTS The MMWR series of publications is published by Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Disease Control Introduction .............................................................................. 2 and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Methods ................................................................................... 2 Services, Atlanta, GA 30333. Results ...................................................................................... 2 Suggested Citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Title]. Surveillance Summaries, [Date]. MMWR 2009;58(No. SS-#). Discussion................................................................................. 5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Conclusion ................................................................................ 7 Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH References ................................................................................ 7 Director Appendix ................................................................................. 8 Peter A. Briss, MD, MPH Acting Associate Director for Science James W. Stephens, PhD Office of the Associate Director for Science Stephen B. Thacker, MD, MSc Acting Deputy Director for Surveillance, Epidemiology, -

Feral Swine Disease Control in China

2014 International Workshop on Feral Swine Disease and Risk Management By Hongxuan He Feral swine diseases prevention and control in China HONGXUAN HE, PH D PROFESSOR OF INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY, CHINESE ACADEMY OF SCIENCES EXECUTIVE DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF NATIONAL RESEARCH CENTER FOR WILDLIFE DISEASES COORDINATOR OF ASIA PACIFIC NETWORK OF WILDLIFE BORNE DISEASES CONTENTS · Feral swine in China · Diseases of feral swine · Prevention and control strategies · Influenza in China Feral swine in China 4 Scientific Classification Scientific name: Sus scrofa Linnaeus Common name: Wild boar, wild hog, feral swine, feral pig, feral hog, Old World swine, razorback, Eurasian wild boar, Russian wild boar Feral swine is one of the most widespread group of mammals, which can be found on every continent expect Antarctica. World distribution of feral swine Reconstructed range of feral swine (green) and introduced populations (blue). Not shown are smaller introduced populations in the Caribbean, New Zealand, sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere. Species of feral swine Now ,there are 4 genera and 16 species recorded in the world today. Western Indian Eastern Indonesian genus genus genus genus Sus scrofa scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa davidi sibiricus vittatus meridionalis Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa algira cristatus ussuricus Sus scrofa Attila Sus scrofa Sus scrofa leucomystax nigripes Sus scrofa Sus scrofa riukiuanus libycus Sus scrofa Sus scrofa majori taivanus Sus scrofa moupinensis Feral swine in China Feral swine has a long history in China. About 10,000 years ago, Chinese began to domesticate feral swine. Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China oracle bone inscriptions of “猪” in Different font of “猪” Shang Dynasty Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China The carving of pig in Han Dynasty Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China In ancient time, people domesticated pig in “Zhu juan”. -

Immunoproteomic Analysis of the Excretory-Secretory Products Of

Wang et al. Parasites & Vectors (2017) 10:579 DOI 10.1186/s13071-017-2522-9 RESEARCH Open Access Immunoproteomic analysis of the excretory-secretory products of Trichinella pseudospiralis adult worms and newborn larvae Yang Wang1†, Xue Bai1†, Haichao Zhu1†, Xuelin Wang1, Haining Shi2, Bin Tang1, Pascal Boireau1,3, Xuepeng Cai4,5, Xuenong Luo5, Mingyuan Liu1,6* and Xiaolei Liu1* Abstract Background: The nematode Trichinella pseudospiralis is an intracellular parasite of mammalian skeletal muscle cells and exists in a non-encapsulated form. Previous studies demonstrated that T. pseudospiralis could induce a lower host inflammatory response. Excretory-secretory (ES) proteins as the most important products of host-parasite interaction may play the main functional role in alleviating host inflammation. However, the ES products of T. pseudospiralis early stage are still unknown. The identification of the ES products of the early stage facilitates the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of the immunomodulation and may help finding early diagnostic markers. Results: In this study, we used two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE)-based western blotting coupled with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS/MS) to separate and identify the T. pseudospiralis adult worms ES products immunoreaction-positive proteins. In total, 400 protein spots were separated by 2-DE. Twenty-eight protein spots were successfully identified using the sera from infected pigs and were characterized to correlate with 12 different proteins of T. pseudospiralis, including adult-specific DNase II-10, poly-cysteine and histidine-tailed protein isoform 2, serine protease, serine/threonine-protein kinase ULK3, enolase, putative venom allergen 5, chymotrypsin-like elastase family member 1, uncharacterized protein, peptidase inhibitor 16, death-associated protein 1, deoxyribonuclease II superfamily and golgin-45. -

1Hfo Lichtarge Lab 2006

Pages 1–7 1hfo Evolutionary trace report by report maker July 28, 2010 4.3.1 Alistat 6 4.3.2 CE 6 4.3.3 DSSP 6 4.3.4 HSSP 7 4.3.5 LaTex 7 4.3.6 Muscle 7 4.3.7 Pymol 7 4.4 Note about ET Viewer 7 4.5 Citing this work 7 4.6 About report maker 7 4.7 Attachments 7 1 INTRODUCTION From the original Protein Data Bank entry (PDB id 1hfo): Title: The structure of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor from trichinella spiralis. CONTENTS Compound: Mol id: 1; molecule: migration inhibitory factor; chain: a, b, c, d, e, f; engineered: yes 1 Introduction 1 Organism, scientific name: Trichinella Spiralis; 1hfo contains a single unique chain 1hfoA (113 residues long) and 2 Chain 1hfoA 1 its homologues 1hfoF, 1hfoD, 1hfoC, 1hfoE, and 1hfoB. 2.1 Q9Y063 overview 1 2.2 Multiple sequence alignment for 1hfoA 1 2.3 Residue ranking in 1hfoA 1 2.4 Top ranking residues in 1hfoA and their position on the structure 1 2.4.1 Clustering of residues at 25% coverage. 1 2 CHAIN 1HFOA 2.4.2 Overlap with known functional surfaces at 2.1 Q9Y063 overview 25% coverage. 2 2.4.3 Possible novel functional surfaces at 25% From SwissProt, id Q9Y063, 98% identical to 1hfoA: coverage. 4 Description: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor like protein. Organism, scientific name: Trichinella spiralis (Trichina worm). 3 Notes on using trace results 5 Taxonomy: Eukaryota; Metazoa; Nematoda; Enoplea; Trichocepha- 3.1 Coverage 5 lida; Trichinellidae; Trichinella.