Frank Stella, Then and Now.” in Frank Stella: Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Barnett Newman's

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Art and Art History Faculty Research Art and Art History Department 2013 Barnett ewN man's “Sense of Space”: A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning Michael Schreyach Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/art_faculty Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Repository Citation Schreyach, M. (2013). Barnett eN wman's “Sense of Space”: A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning. Common Knowledge, 19(2), 351-379. doi:10.1215/0961754X-2073367 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art and Art History Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Art History Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES BARNETT NEWMAN’S “SENSE OF SPACE” A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning Michael Schreyach Dorothy Seckler: How would you define your sense of space? Barnett Newman: . Is space where the orifices are in the faces of people talking to each other, or is it not [also] between the glance of their eyes as they respond to each other? Anyone standing in front of my paint- ings must feel the vertical domelike vaults encompass him [in order] to awaken an awareness of his being alive in the sensation of complete space. This is the opposite of creating an environment. This is the only real sensation of space.1 Some of the titles that Barnett Newman gave to his paintings are deceptively sim- ple: Here and Now, Right Here, Not There — Here. -

Art and Politics: a Small History of Art for Social Change Since 1945 Free

FREE ART AND POLITICS: A SMALL HISTORY OF ART FOR SOCIAL CHANGE SINCE 1945 PDF Claudia Mesch | 224 pages | 15 Oct 2013 | I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd | 9781848851108 | English | London, United Kingdom 15 Influential Political Art Pieces | Widewalls What is political art? Is it different than the art itself and could it be the art beside the politics, as we know the political truth is the ruling mechanism over all aspects of humanity? From its beginnings, art is inseparable from the societies and throughout its history authors always reflected the present moment bringing the artistic truth to the general public. For Plato and Aristotle, mimesis - the act of artistic creation is inseparable from the notion of real world, in which art represents or rather disputes the various models of beauty, truth, and the good within the societal reality. Hence, position of the art sphere is semi- autonomous, as it is independent field of creation freed from the rules, function and norms, but on the other hand, art world is deeply connected and dependent from artistic productionways of curating and display as well as socio-economical conditions and political context. In times of big political changes, many art and cultural workers choose to reflect the context within their artistic practices and consequently to create politically and socially engaged art. Art could be connected to politics in many different ways, and the field of politically engaged art is rather broad and rich than a homogenous term reducible to political propaganda. There are many strategies to reach the state of political engagement in art and it includes the wide scale of artistic interventions from bare gestures to complex conceptual pieces with direct political engagement intended to factual political changes. -

The Creative Arts at Brandeis by Karen Klein

The Creative Arts at Brandeis by Karen Klein The University’s early, ardent, and exceptional support for the arts may be showing signs of a renaissance. If you drive onto the Brandeis campus humanities, social sciences, and in late March or April, you will see natural sciences. Brandeis’s brightly colored banners along the “significant deviation” was to add a peripheral road. Their white squiggle fourth area to its core: music, theater denotes the Creative Arts Festival, 10 arts, fine arts. The School of Music, days full of drama, comedy, dance, art Drama, and Fine Arts opened in 1949 exhibitions, poetry readings, and with one teacher, Erwin Bodky, a music, organized with blessed musician and an authority on Bach’s persistence by Elaine Wong, associate keyboard works. By 1952, several Leonard dean of arts and sciences. Most of the pioneering faculty had joined the Leonard Bernstein, 1952 work is by students, but some staff and School of Creative Arts, as it came to faculty also participate, as well as a be known, and concentrations were few outside artists: an expert in East available in the three areas. All Asian calligraphy running a workshop, students, however, were required to for example, or performances from take some creative arts and according MOMIX, a professional dance troupe. to Sachar, “we were one of the few The Wish-Water Cycle, brainchild of colleges to include this area in its Robin Dash, visiting scholar/artist in requirements. In most established the Humanities Interdisciplinary universities, the arts were still Program, transforms the Volen Plaza struggling to attain respectability as an into a rainbow of participants’ wishes academic discipline.” floating in bowls of colored water: “I wish poverty was a thing of the past,” But at newly founded Brandeis, the “wooden spoons and close friends for arts were central to its mission. -

The Surprising Tale of One of Frank Stella's Black Paintings

The Surprising Tale of One of Frank Stellaʼs Black Paintings - The New York Times 2/18/19, 1509 The Surprising Tale of One of Frank Stella’s Black Paintings By Ted Loos Feb. 17, 2019 At 82, the artist Frank Stella has done it all and isn’t terribly concerned what anyone thinks. He is matter-of-fact and unguarded, secure on his perch in the pantheon after two solo retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art. He can — and did — wear white house-slippers to an interview and photo shoot. Deal with it. Mr. Stella became art-famous not long after graduating from Princeton in 1958, and he has been lauded for achievements like his early Black Paintings, with their dazzling geometric rigor and their power to inspire statements like his “What you see is what you see.” His work evolved over the decades — the brightly colored Protractor series became a landmark of contemporary art, too, and eventually his work got sculptural and very big. His studio is now in the Hudson Valley, where he goes often to make pieces that require a lot of space, like “adjoeman” (2004), a stainless steel and carbon fiber sculpture weighing some 3,000 pounds that was once featured on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. But he and his wife, Harriet McGurk, a pediatrician, live in the same three-story house in Greenwich Village that he acquired in the late 1960s. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/17/arts/design/frank-stella-black-p…=package&version=highlights&contentPlacement=5&pgtype=sectionfront Page 1 of 13 The Surprising Tale of One of Frank Stellaʼs Black Paintings - The New York Times 2/18/19, 1509 It’s packed with art — there are many large, midcentury abstractions by friends, peers and those he admired when he started, including Jules Olitski, Hans Hoffman and Kenneth Noland. -

Dick Polich in Art History

ww 12 DICK POLICH THE CONDUCTOR: DICK POLICH IN ART HISTORY BY DANIEL BELASCO > Louise Bourgeois’ 25 x 35 x 17 foot bronze Fountain at Polich Art Works, in collaboration with Bob Spring and Modern Art Foundry, 1999, Courtesy Dick Polich © Louise Bourgeois Estate / Licensed by VAGA, New York (cat. 40) ww TRANSFORMING METAL INTO ART 13 THE CONDUCTOR: DICK POLICH IN ART HISTORY 14 DICK POLICH Art foundry owner and metallurgist Dick Polich is one of those rare skeleton keys that unlocks the doors of modern and contemporary art. Since opening his first art foundry in the late 1960s, Polich has worked closely with the most significant artists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. His foundries—Tallix (1970–2006), Polich of Polich’s energy and invention, Art Works (1995–2006), and Polich dedication to craft, and Tallix (2006–present)—have produced entrepreneurial acumen on the renowned artworks like Jeff Koons’ work of artists. As an art fabricator, gleaming stainless steel Rabbit (1986) and Polich remains behind the scenes, Louise Bourgeois’ imposing 30-foot tall his work subsumed into the careers spider Maman (2003), to name just two. of the artists. In recent years, They have also produced major public however, postmodernist artistic monuments, like the Korean War practices have discredited the myth Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC of the artist as solitary creator, and (1995), and the Leonardo da Vinci horse the public is increasingly curious in Milan (1999). His current business, to know how elaborately crafted Polich Tallix, is one of the largest and works of art are made.2 The best-regarded art foundries in the following essay, which corresponds world, a leader in the integration to the exhibition, interweaves a of technological and metallurgical history of Polich’s foundry know-how with the highest quality leadership with analysis of craftsmanship. -

The Face of NGA to Change with Barnett Newman Sculpture

MEDIA RELEASE 15 FEBRUARY 2018 THE FACE OF THE NGA TO CHANGE WITH BARNETT NEWMAN SCULPTURE The National Gallery of Australia is celebrating the installation of Barnett Newman’s ground- breaking sculpture, Broken Obelisk, outside the Gallery’s main entrance in Canberra. The display of this well-known, gravity-defying work reflects the dynamic and evolving face of Australia’s iconic national art institution and foreshadows American Masters, the NGA’s upcoming major exhibition of its unrivalled collection of 20th century American masterpieces, opening 24 August. ‘Barnett Newman is one of the most prominent figures in Abstract Expressionism’, said Gerard Vaughan, NGA Director. ‘We are thrilled by the generosity of the Barnett Newman Foundation in lending this extraordinary sculpture to the heart of Canberra. The NGA is world-famous for its collection of 20th century American art, and it is fitting that this iconic sculpture has transformed the entrance to the Gallery as a signpost to the great treasures of the New York school installed inside.’ With the installation of Broken Obelisk, the NGA aligns itself with its international counterparts in displaying one of the most significant works of modern sculpture. Broken Obelisk is one of four versions in existence. The first two sculptures, conceived in 1963 and produced in 1966–67, are on display at the Rothko Chapel, Houston and the University of Washington’s Red Square; the third version, made in 1969, takes pride of place in the open courtyard of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. A monumental sculpture created with rough weathering steel, Broken Obelisk represents the American artist at his best. -

Aria Amenities Fine Art Brochure

YOUR GUIDE TO EXPLORING THE Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation The first major permanent collection of art in Las Vegas to be integrated into a public space, the ARIA Fine Art Collection is one of the world’s largest and most ambitious corporate collections. The ARIA Fine Art Collection features work by acclaimed painters, sculptors and installation artists, including Maya Lin, Jenny Holzer, Nancy Rubins, Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Frank Stella, Henry Moore, James Turrell and Richard Long, among others. The ARIA Fine Art Collection encompasses a multitude of styles and media engaging visitors on a visual and intellectual level. Some were existing pieces, carefully chosen for their artistic value and cultural significance; others are site-specific installations for which the artist commanded their vision over the space. Fully integrated into the architecture and design of the ARIA Campus, guests can interact with important works of art in the living, breathing spaces of ARIA’s public areas, hotels and residential common spaces. From vibrant and ornate to intimate and serene, these works were strategically placed to fascinate and educate guests. For more information about the ARIA Fine Art Collection, please visit Aria.com/fineart. Please do not touch the artwork. 11 6 12 5 4 9 13 ADDITIONAL ATTRACTIONS TO CASINO ND LEVEL 7 10 PROMENADE ARIA Resort & Casino 3 8 A Lumia ARIA Resort & Casino, Main Entrance Twisting ribbons and large arcs of streaming water create bold, captivating “water sparks” at their intersections. Lumia is the first fountain to be lit, so the vibrant colors are visible during daylight. -

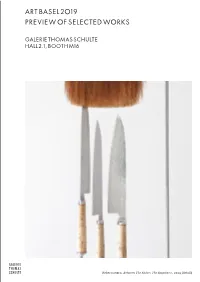

Art Basel 2019 Preview of Selected Works

ART BASEL 2019 PREVIEW OF SELECTED WORKS GALERIE THOMAS SCHULTE HALL 2.1, BOOTH M16 • Rebecca Horn, Between The Knives The Emptiness, 2014 (detail) Artists on view Also represented Contact Angela de la Cruz Dieter Appelt Galerie Thomas Schulte Hamish Fulton Alice Aycock Charlottenstraße 24 Rebecca Horn Richard Deacon 10117 Berlin Idris Khan David Hartt fon: +49 (0)30 2060 8990 Jonathan Lasker Julian Irlinger fax: +49 (0)30 2060 89910 Michael Müller Alfredo Jaar [email protected] Albrecht Schnider Paco Knöller www.galeriethomasschulte.de Pat Steir Allan McCollum Juan Uslé Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle Thomas Schulte Stephen Willats Robert Mapplethorpe PA Julia Ben Abdallah Fabian Marcaccio [email protected] Gordon Matta-Clark João Penalva Gonzalo Alarcón David Reed +49 (173) 66 46 623 Leunora Salihu [email protected] Iris Schomaker Katharina Sieverding Eike Dürrfeld Jonas Weichsel +49 (172) 30 89 074 Robert Wilson [email protected] Luigi Nerone +49 (172) 30 89 076 [email protected] Juliane Pönisch +49 (151) 22 22 02 70 [email protected] Galerie Thomas Schulte is very pleased to present at this year’s Art Basel recent works by Rebecca Horn, whose exhibition Body Fantasies will be on view at Basel’s Museum Tinguely during the time of the fair (until 22 September). Our booth will also feature works by Angela de la Cruz, Hamish Fulton, Idris Khan, Jonathan Lasker, Michael Müller, Albrecht Schnider, Pat Steir, Juan Uslé and Stephen Willats. This brochure represents a selection of the works at our booth. For further information and to learn more about works which are not shown here, please do not hesitate to contact us. -

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-To-Reel Collection Barnett Newman and Thomas Hess in Conversation, 1966

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection Barnett Newman and Thomas Hess in Conversation, 1966 MALE 1 ...these lectures. Before announcing today’s program, I would like to inform you that two weeks from today, the last program will consist of a lecture delivered by Professor William Rubin on the subject of color in modern American painting. One further announcement: I think many of you came here today fully expecting to find Harold Rosenberg as the other participant with Barnett Newman in the conversation. Unfortunately, Mr. Rosenberg was unable to come; he is teaching in the Midwest and was making a special trip to New York for this program, but at the very last moment something arose which made it impossible for him to be here. And so we were very grateful that Thomas Hess volunteered to take Harold Rosenberg’s place. And so [00:01:00] our subject today has been retitled, “Conversation with Hess and Newman.” Thomas Hess, writer and editor of Art News, is very well known to all of us. He has held this position on that important publication since 1949, having joined the staff of Art News just a few years before. He has always been considered a leading spokesman for and about the movement of new American painting which emerged after the war. He is an author of two very popular, well- known books on American art, one entitled Abstract Painting and the other a monograph on the work of Willem de Kooning. Aside from his editorial work on Art News, he is a frequent contributor to the New York [00:02:00] Times, the Saturday Review, Encounter, and numerous other publications. -

Abstraction: on Ambiguity and Semiosis in Abstract Painting

Abstraction: On Ambiguity and Semiosis in Abstract Painting Joseph Daws Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Visual Arts Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2013 2 Abstract This research project examines the paradoxical capacity of abstract painting to apparently ‘resist’ clear and literal communication and yet still generate aesthetic and critical meaning. My creative intention has been to employ experimental and provisional painting strategies to explore the threshold of the readable and the recognisable for a contemporary abstract painting practice. Within the exegetical component I have employed Damisch’s theory of /cloud/, as well as the theories expressed in Gilles Deleuze’s Logic of Sensation, Jan Verwoert ‘s writings on latency, and abstraction in selected artists’ practices. I have done this to examine abstract painting’s semiotic processes and the qualities that can seemingly escape structural analysis. By emphasizing the latent, transitional and dynamic potential of abstraction it is my aim to present a poetically-charged comprehension that problematize viewers’ experiences of temporality and cognition. In so doing I wish to renew the creative possibilities of abstract painting. 3 Keywords abstract, ambiguity, /cloud/, contemporary, Damisch, Deleuze, latency, transition, painting, passage, threshold, semiosis, Verwoert 4 Signed Statement of Originality The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature: Date: 6th of February 2014 5 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my Principal Supervisor Dr Daniel Mafe and Associate Supervisor Dr Mark Pennings and acknowledge their contributions to this research project. -

Miguel Abreu Gallery

miguel abreu gallery FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Exhibition: Pieter Schoolwerth Model as Painting Dates: May 21 – June 30, 2017 Reception: Sunday, May 21, 6 – 8PM Miguel Abreu Gallery is pleased to announce the opening on Sunday, May 21st, of Model as Painting, Pieter Schoolwerth’s sixth solo exhibition at the gallery. The show will be held at both our 88 Eldridge and 36 Orchard Street locations. One of the clear characteristics of our digital age is that in it all things, bodies even are generally suspended from their material substance. This increasingly spectral state of affairs is the effect of mostly invisible forces of abstraction that can be associated with the digitization of more and more aspects of experience. We as living beings are now confronting a structural split between the substance of things and their virtual double. To speak concretely, one can point to everyday phenomena such as coffee without caffeine, or food without fat, for example, but also to money without currency, love without bodies, and soon following, to painting without paint, and art without art… In Model as Painting, Pieter Schoolwerth attempts to reverse the above described techno-cultural trend by producing a series of ‘in the last instance’ paintings, in which the stuff of paint itself reappears at the very end only of a complex, multi-media effort to produce a figurative picture. As such, paint here is not immediately used to build up an image from the ground up, if you will, one brush stroke at a time, but rather it arrives only to mark the painting after it has been fully formed and output onto canvas.