Re)Contextualising Audience Receptions of Reality TV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obituaries for Cookeville City Cemetery, Cookeville, Tn D

OBITUARIES FOR COOKEVILLE CITY CEMETERY, COOKEVILLE, TN & additional information D - G (Compiled by Audrey J. (Denny) Lambert for her website at: http://www.ajlambert.com ) Sources: Putnam County Cemeteries by Maurine Ensor Patton & Doris (Garrison) Gilbert; Allison Connections by Della P. Franklin, 1988; Boyd Family by Carol Bradford; Draper Families in America, 1964; census records; Putnam County Herald & Herald-Citizen obts; Tennessee DAR GRC report, S1 V067: City Cemetery Cookeville, Putnam Co., TN, 1954; names, dates and information obtained from tombstones and research by Audrey J. (Denny) Lambert and others. Office & Cemetery located at: 241 S Walnut Ave Cookeville, TN 38501 (931) 372-8086 GPS Coordinates: Latitude: 36.15947, Longitude: -85.50776 Earl Jefferson Dabbs b. 22 June 1901, TN – d. 11 March 1976, md on the 26th of May 1934 to Linnie Belle (Cleghorn) Dabbs, b. 29 July 1904 – d. 15 March 1971. Earl J. Dabbs, s/o William Jefferson Dabbs (1872-1947) & Nora Edna Williams (1882-1941). *See William Jefferson Dabbs Obt. (1910 census 1st Civil Dist., Cookeville Town, Railroad St., Putnam Co., TN: Dwl: 311 – William J. Dabbs is head of household, 37 yrs. old, TN (father born in VA, mother, TN), Occupation: Police Town, md 10 yrs. to Nora, 27 yrs. old, TN, 5 children born, 5 children living. Children: Earl J., 8 yrs. old; William H., 5 yrs. old; Balie C., 3 yrs. old; Mary A., 2 yrs. old & Peat J. Dabbs, 2/12 yrs. old. All born in TN). (1920 census 1st Civil Dist., Cookeville Town, Broad Street, Putnam Co., TN: Dwl: 515-151-176 - William J. -

Radio 2 Paradeplaat Last Change Artiest: Titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley

Radio 2 Paradeplaat last change artiest: titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley Moody Blue 10 2 David Dundas Jeans On 15 3 Chicago Wishing You Were Here 13 4 Julie Covington Don't Cry For Me Argentina 1 5 Abba Knowing Me Knowing You 2 6 Gerard Lenorman Voici Les Cles 51 7 Mary MacGregor Torn Between Two Lovers 11 8 Rockaway Boulevard Boogie Man 10 9 Gary Glitter It Takes All Night Long 19 10 Paul Nicholas If You Were The Only Girl In The World 51 11 Racing Cars They Shoot Horses Don't they 21 12 Mr. Big Romeo 24 13 Dream Express A Million In 1,2,3, 51 14 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 19 15 Champagne Oh Me Oh My Goodbye 2 16 10CC Good Morning Judge 12 17 Glen Campbell Southern Nights 15 18 Andrew Gold Lonely Boy 28 43 Carly Simon Nobody Does It Better 51 44 Patsy Gallant From New York to L.A. 15 45 Frankie Miller Be Good To Yourself 51 46 Mistral Jamie 7 47 Steve Miller Band Swingtown 51 48 Sheila & Black Devotion Singin' In the Rain 4 49 Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers Egyptian Reggae 2 1978 11 Chaplin Band Let's Have A Party 19 1979 47 Paul McCartney Wonderful Christmas time 16 1984 24 Fox the Fox Precious little diamond 11 52 Stevie Wonder Don't drive drunk 20 1993 24 Stef Bos & Johannes Kerkorrel Awuwa 51 25 Michael Jackson Will you be there 3 26 The Jungle Book Groove The Jungle Book Groove 51 27 Juan Luis Guerra Frio, frio 51 28 Bis Angeline 51 31 Gloria Estefan Mi tierra 27 32 Mariah Carey Dreamlover 9 33 Willeke Alberti Het wijnfeest 24 34 Gordon t Is zo weer voorbij 15 35 Oleta Adams Window of hope 13 36 BZN Desanya 15 37 Aretha Franklin Like -

Jason Newsted, Art and Loud

Jason Newsted: Art Out Loud By Juan Sagarbarria ! JUPITER, FL October 30, 2017 An energetic and highly amplified electronic rock music having a hard beat, that is how Merriam-Webster defines heavy metal. If there was a viable channel in which to personify this description, then Jason Newsted would surely be one of its embodiments. A six-time Grammy winner, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame artist, Newsted—also known as “Jasonic”—is the former bassist of the band that arguably bred the metal genre—Metallica. From 1986 to 2001, Newsted forged his name in the annals of rock history with his beefy, fast-paced, and at times, nostalgic bass lines, as Metallica took the world by storm. Eternal staples like “Enter Sandman,” “The Unforgiven,” “Nothing Else Matters,” “One,” and “Fuel,” are but a brief sampling of the songs that were hatched during Newsted’s tenure. By singing lead on a few songs during the band’s live performances and astounding countless audiences with his remarkable bass solos, Newsted stamped his musical footprint. He even took over lead vocals for a whole show at the Kentucky Speedway during the 1999 Summer Sanitarium Tour, while frontman James Hetfield recovered from injury—and fiercely delivered. “I got to join my favorite band,” Newsted remarks. “I got real, real f***** lucky and got to travel around the world five times. Just imagine being in a dreamlike state for 15 years—that is the only way I could sum up what the experience entailed. Suffice it to say, I had too much fun.” Upon meeting Newsted, my impression of him was that, although he did not have his characteristic long hair that flailed aggressively during his early days with Metallica, he is still as spirited as ever; a character’s character. -

COMUNICATO STAMPA NR. 07 a Gordevio Una Tre Giorninel Segno

Avegno, 25 luglio 2021 COMUNICATO STAMPA NR. 07 Le foto delle serate si trovano al seguente link: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/zwqce6h9fgktaxf/AACXZsvVoCAenY4jUB3C27SWa?dl=0 A Gordevio una tre giorni nel segno del Flower Power e dei mitici anni ’70. Per quanto riguarda la qualità delle proposte musicali il Vallemaggia Magic Blues ha mantenuto tutte le promesse della vigilia, anzi con qualcosina in più. Ora spazio alla tre giorni di Gordevio, quasi tutta nel segno del Flower Power e dei mitici anni ’70: “50 years - From Flower Power to Hard Rock”. Sul campetto aleggeranno gli spiriti di Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon e dei Thin Lizzy. La prima serata, “Let's celebrate John Lennon and Jimi Hendrix“ prevede un doveroso omaggio a John Lennon (a 41 anni dalla morte, a Jimi Hendrix (che ci ha lasciati 51 anni fa). Gli Instant Karma sono la prima John Lennon Tribute Band in Svizzera, nata a Lugano e attiva da tempo non solo in Ticino, ma anche nel resto della Svizzera e nella vicina penisola. Spesso si pensa a John Lennon come leader dei Beatles o come autore di grandi pezzi ormai ritenuti dei classici, come Imagine, Woman o Jealous Guy. L’intendo della band è invece quello di riproporre ad un vasto pubblico il repertorio di un artista poliedrico, che spazia attraverso vari generi e decenni. Così gli Instant Karma partono dai brani del Lennon solista, passando attraverso pezzi degli ultimi Beatles, energici e graffianti come Come together, per poi rendere omaggio al Rock’n’Roll degli anni 50, una delle grandi passioni di Lennon. -

Drummer Bracket Template

First Round Second Round Sweet 16 Elite 8 Final Four Championship Final Four Elite 8 Sweet 16 Second Round First Round Peter Criss-Kiss Robert Bourbon-Linkin Park Neal Sanderson-Three Days Grace Neal Sanderson-Three Days Grace Morgan Rose-Sevendust Morgan Rose-Sevendust Matt Sorem-GNR Paul Bostaph-Slayer Clown-Slipknot Charlie Benante-Anthrax Paul Bostaph-Slayer Paul Bostaph-Slayer Morgan Rose-Sevendust Clown-Slipknot Ray Luzier-KoRn Matt McDonough-Mudvayne Neal Peart-Rush Matt Cameron-Pearl Jam Ginger Fish-Manson Ray Luzier-KoRn Winner Matt Cameron-Pearl Jam Joey Kramer-Aerosmith Matt McDonough-Mudvayne Matt McDonough-Mudvayne Neal Peart-Rush Neal Peart-Rush Chad Gracey-Live Matt McDonough-Mudvayne Vinnie Paul-Pantera Neal Peart-Rush Sam Loeffler-Chevelle Lars Ulrich-Metallica Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Shannon Larkin-Godsmack Taylor Hawkins-Foo Roy Mayogra-Stone Sour Lars Ulrich-Metallica Taylor Hawkins-Foo Fighters Ben Anderson-Nothing More Jay Weinberg-Slipknot Jay Weinberg-Slipknot Ron Welty-Offspring Ron Welty-Offspring Alex Shelnett-ADTR Jay Weinberg-Slipknot Taylor Hawkins-Foo Fighters Butch Vig-Garbage Vinnie Paul-Pantera Tre Cool-Green Day Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Shannon Larkin-Godsmack Eric Carr-Kiss John Alfredsson-Avatar Tre Cool-Green Day Neal Peart-Rush Robb Rivera-Nonpoint Robb Rivera-Nonpoint Bill Ward-Black Sabbath Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Shannon Larkin-Godsmack Shannon Larkin-Godsmack Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Chris Adler-Lamb of God Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Neal Peart-Rush Vinnie Paul-Pantera Joey Jordison-Slipknot Sean Kinney-Alice -

OP 323 Sex Tips.Indd

BY PAUL MILES Copyright © 2010 Paul Miles This edition © 2010 Omnibus Press (A Division of Music Sales Limited) Cover and book designed by Fresh Lemon ISBN: 978.1.84938.404.9 Order No: OP 53427 The Author hereby asserts his/her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages. Exclusive Distributors Music Sales Limited, 14/15 Berners Street, London, W1T 3LJ. Music Sales Corporation, 257 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10010, USA. Macmillan Distribution Services, 56 Parkwest Drive Derrimut, Vic 3030, Australia. Printed by: Gutenberg Press Ltd, Malta. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Visit Omnibus Press on the web at www.omnibuspress.com For more information on Sex Tips From Rock Stars, please visit www.SexTipsFromRockStars.com. Contents Introduction: Why Do Rock Stars Pull The Hotties? ..................................4 The Rock Stars ..........................................................................................................................................6 Beauty & Attraction .........................................................................................................................18 Clothing & Lingerie ........................................................................................................................35 -

Episode 34: Catch a Kite 4 Air Date: September 11, 2019

Episode 34: Catch a Kite 4 Air Date: September 11, 2019 Cori Thomas: [00:00] I'm Cori Thomas, writer of the play Lockdown. This episode of Ear Hustle contains explicit language. Please be advised, this may not be for every listener. Discretion is advised. [00:11] [Footsteps on concrete backed by minimal music that fades out] Rahsaan “New York” Thomas: [00:16] Can you show Nigel the two signs you showed me today? [Tommy laughs] Tommy Wickerd: [00:24] Really? [Laughs] Nigel Poor: [00:24] [Inaudible] [From a distance] Did they get it? New York: [00:26] That’s the sign for bullshit. [All laugh] Nigel: [00:29] [Laughs] You think I'm not going to learn that one right away? Well everyone… Tommy: [00:31] I was all thinking Ear Hustle, right? Nigel: [00:34] [Still in the distance] I gotta admit that’s… 1 New York: [00:35] Teach us that! How do you do the Ear Hustle sign? Tommy: [00:36] Grab your ear, make an “H” and go twice. New York: [00:39] [In the distance] What after this? Just like this? Tommy: [00:40] “H” Nigel: [00:41] Oh. Tommy: [00:41] Ear. Hustle. That’s the sign for the day. [Laughs] [00:46] [Opening theme music begins] New York: [00:52] You are now tuned into Ear Hustle from PRX’s Radiotopia. I am Rahsaan “New York” Thomas, a resident of San Quentin State Prison in California. Nigel: [1:02] And I'm Nigel Poor. I've been working with the guys here at San Quentin for about eight years now. -

Mötley Crüe Successfully Moves for Dismissal of Suit Involving Copyright in “Too Fast for Love” Album Artwork

Mötley Crüe Successfully Moves for Dismissal of Suit Involving Copyright in “Too Fast for Love” Album Artwork October 15, 2012 by Jeffrey A. Wakolbinger On October 9, 2012, Judge Grady, in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, dismissed a copyright-infringement action against rock band Mötley Crüe for lack of personal jurisdiction.1 The suit was brought by Ron Toma, who owns copyrights in certain photographs of band members Vince Neil, Nikki Sixx, Mick Mars, and Tommy Lee. One of those photographs was a close up of singer Vince Neil’s waist area, featuring a prominent studded belt buckle (the “Belt Buckle Image”). The photograph was taken by Michael Pinter in 1981 and used as the cover artwork for Mötley Crüe’s debut album, “Too Fast for Love.” Toma acquired the copyright in that image in 2008 through assignment. In September 2011, he filed a complaint in the Northern District of Illinois 1 Toma v. Motley Crue, Inc., No. 11 C 6766 (N.D. Ill. Oct. 9, 2012). These materials have been prepared by Pattishall, McAuliffe, Newbury, Hilliard & Geraldson LLP for general informational purposes only. They are not legal advice. They are not intended to create, and their receipt by you does not create, an attorney-client relationship. against Motley Crue, Inc., alleging that the defendants infringed his copyright in the Belt Buckle Image by projecting it on screen during live performances. He later amended the complaint to add the band’s touring company, Red White & Crue, Inc, as a defendant. The only specific example of alleged infringement in the complaint is a link to a YouTube video showing live footage from a concert in Las Vegas, during which the Belt Buckle Image was displayed on a screen while the band performed the title track of the album. -

Grolier, Europe 1 Launch

FEBRUARY 12, 2000 Music Volume 17, Issue 7 £3.95 Gabrielleis on theRise, with her Go! Beat single bursting into the Eurochart Hot 100 this week as the Media® highest new entry. we tallerd M'ail.41:721_1_4C10 M&M chart toppers this week Grolier, Europe 1 launch 'Net venture Eurochart Hot 100 Singles by Emmanuel Legrand music -related offers and is presented Brunet, who has had a long career EIFFEL65 as "a free full -service portal for French in radio, and a stint in the music Move Your Body PARIS - Europe 1 Communication, one and European music" and a window forindustry as MD of BMG France in the (Bliss Co.) of Europe's leading radio groups, andnew talent and new musical trends. mid -'80s, says one of his goals with the European Top 100 Albums multimedia company Grolier Interac- MCity.fr managing Internet is to go back to the basics of tive-both part of Lagardere Group-director Claude Brunet radio, when the medium was a plat- SANTANA have established a major presence onsays the portal will be form for new talent. Supernatural theInternet with the February 2 open to all musical gen- Users will be able to (Arista) launch of MCity.fr, the first Frenchres with the aim of F.-access information on European Radio Top 50 music -only Internet portal, alongside "favouring creative, music and artists, use various services such as a directory of CHRISTINA AGUILERA 12 new on-line radio stations. quality music in partner- Designed by a team of 30 program-ship with all participants in the music 10,000 music sites, download music What A Girl Wants mers, DJs, producers and journalists,world-musicians, writers, producers,and also streamline the different 'Net (RCA) MCity.fr will provide a wide range oflabels, distributors and the media." continued on page 21 European Dance Traxx EIFFEL65 Move Your Body RAJARs reveal BBC boom (Bliss Co.) by Jon Heasman share of listening, compared to com- mercial radio's 46.7%, giving the BBC Inside M&M this week LONDON - The UK's commercial radio a 4.6% lead. -

All Audio Songs by Artist

ALL AUDIO SONGS BY ARTIST ARTIST TRACK NAME 1814 INSOMNIA 1814 MORNING STAR 1814 MY DEAR FRIEND 1814 LET JAH FIRE BURN 1814 4 UNUNINI 1814 JAH RYDEM 1814 GET UP 1814 LET MY PEOPLE GO 1814 JAH RASTAFARI 1814 WHAKAHONOHONO 1814 SHACKLED 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 20 FINGERS SHORT SHORT MAN 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 JAYS IN MY EYES 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO 3 THE HARDWAY ITS ON 360 FT GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU 360 FT JOSH PYKE THROW IT AWAY 3OH!3 STARSTRUKK ALBUM VERSION 3OH!3 DOUBLE VISION 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 3OH!3 AND KESHA MY FIRST KISS 4 NON BLONDES OLD MR HEFFER 4 NON BLONDES TRAIN 4 NON BLONDES PLEASANTLY BLUE 4 NON BLONDES NO PLACE LIKE HOME 4 NON BLONDES DRIFTING 4 NON BLONDES CALLING ALL THE PEOPLE 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 4 NON BLONDES SUPERFLY 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN 4 NON BLONDES MORPHINE AND CHOCOLATE 4 NON BLONDES DEAR MR PRESIDENT 48 MAY NERVOUS WRECK 48 MAY LEATHER AND TATTOOS 48 MAY INTO THE SUN 48 MAY BIGSHOCK 48 MAY HOME BY 2 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER GOOD GIRLS 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER EVERYTHING I DIDNT SAY 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER DONT STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER KISS ME KISS ME 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT WINDOW SHOPPER 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT AND JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 6400 CREW HUSTLERS REVENGE 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT A GREAT BIG WORLD FT CHRISTINA AGUILERA SAY SOMETHING A HA THE ALWAYS SHINES ON TV A HA THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS A LIGHTER SHADE OF BROWN ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON -

Complete Book of Witchcraft Was Born When One of the Cavemen Threw on a Skin and Antlered Mask and Played the Part of the Hunting God, Directing the Attack

INTRODUCTION Witchcraft is not merely legendary; it was, and is, real. It is not extinct; it is alive and prospering. Since the last laws against Witchcraft were repealed (as recently as the 1950s), Witches have been able to come out into the open and show themselves for what they are. And what are they? They are intelligent, community-conscious, thoughtful men and women of TODAY. Witchcraft is not a step backwards; a retreat into a more superstition-filled time. Far from it. It is a step forward. Witchcraft is a religion far more relevant to the times than the vast majority of the established churches. It is the acceptance of personal and social responsibility. It is acknowledgement of a holistic universe and a means towards a raising of consciousness. Equal rights; feminism; ecology; attunement; brotherly/sisterly love; planetary care—these are all part and parcel of Witchcraft, the old yet new religion. The above is certainly not what the average person thinks of in relation to "Witchcraft". No; the misconceptions are deeply ingrained, from centuries of propaganda. How and why these misconceptions came about will be examined later. With the spreading news of Witchcraft—what it is; its relevance in the world today—comes "The Seeker". If there is this alternative to the conventional religions, this modern, forward-looking approach to life known as "Witchcraft", then how does one become a part of it? There, for many, is the snag. General information on the Old Religion—valid information, from the Witches themselves—is available, but entry into the order is not. -

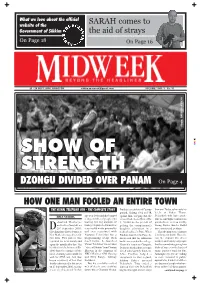

Midweek: Beyond the Headlines

20 - 26 Sept, 2006 111 What we love about the official website of the SARAH comes to Government of Sikkim the aid of strays On Page 18 On Page 16 20 - 26 SEPT, 2006, GANGTOK [email protected] VOLUME 1 NO. 3. Rs. 10 Photo: SARIKAH ATREYA Photo: SARIKAH K Y M SHOWSHOW OFOF C STRENGTHSTRENGTH DZONGU DIVIDED OVER PANAM On Page 4 HOW ONE MAN FOOLED AN ENTIRE TOWN THE VISHAL TELEFILMS CON - THE COMPLETE STORY Pradhan, a resident of Convoy than one. Today, as he cools his ground, Tadong, filed an FIR heels at Sadar Thana, RHEA SHARMA one year Debashish had conned against him, alleging that the Debashish will have ample a large number of people into accused had cheated him of Rs. time to contemplate on how his ebashish Mukherjee loaning him big amounts of 1, 78,800 on the pretext of grand scheme went so terribly arrived in Gangtok on money. He projected himself as getting the complainant’s wrong. Earlier than he would D 28th September 2005. a successful media personality daughter admission in a have anticipated, perhaps. Checking into Hotel Sernya at and even negotiated with medical college in Pune. When That the man was a charmer New Market, he stayed here for Nayuma Television for a Pradhan travelled to Pune, he is no longer in doubt. How else two days. This pattern was programming tie-up. With discovered that no admission can we explain the sheer repeated the next month and much fanfare he launched had been secured at the college.