Reputational Sanctions in China's Securities Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Netizens, Nationalism, and the New Media by Jackson S. Woods BA

Online Foreign Policy Discourse in Contemporary China: Netizens, Nationalism, and the New Media by Jackson S. Woods B.A. in Asian Studies and Political Science, May 2008, University of Michigan M.A. in Political Science, May 2013, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2017 Bruce J. Dickson Professor of Political Science and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Jackson S. Woods has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of September 6, 2016. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Online Foreign Policy Discourse in Contemporary China: Netizens, Nationalism, and the New Media Jackson S. Woods Dissertation Research Committee: Bruce J. Dickson, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Dissertation Director Henry J. Farrell, Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Committee Member Charles L. Glaser, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Committee Member David L. Shambaugh, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2017 by Jackson S. Woods All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments The author wishes to acknowledge the many individuals and organizations that have made this research possible. At George Washington University, I have been very fortunate to receive guidance from a committee of exceptional scholars and mentors. As committee chair, Bruce Dickson steered me through the multi-year process of designing, funding, researching, and writing a dissertation manuscript. -

Mizuho China Business Express Economic Journal (No

October 27, 2017 Mizuho Bank (China), Ltd. Advisory Division ―The macroeconomy― Mizuho China Business Express Economic Journal (No. 72) Summary Though China’s real GDP growth rate slowed slightly to +6.8% y-o-y in July–September, it remained above the 2017 government’s target of ‘around +6.5%.’ Xi Jinping unveiled his ‘Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’ at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. In his report, Xi Jinping said that after the Party had finished building a moderately prosperous society in all respects by 2020, a two-step approach should be taken (the first step from 2020 to 2035 and the second step from 2035 onwards) to build China into a ‘great modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious, and beautiful’ by the middle of the century. 1. September’s economic indicators improved on the previous month ・ Growth slowed to +6.8% over July–September ・ Production, investment and consumption all accelerated ・ The floor space of residential buildings sold grew at a slower y-o-y pace for the first time since March 2015 ・ Imports and exports both improved ・ CPI growth slowed while PPI growth accelerated ・ Net new loans and total social financing both increased 2. Topics: The economic policy position revealed at the National Congress ・ A change in the ‘principal contradiction facing Chinese society’ ・ Building a ‘great modern socialist country’ by the middle of the century - 1 - 1. September’s economic indicators improved on the previous month ・Growth slowed to +6.8% over July–September On October 19, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) announced that China’s real GDP growth rate had hit +6.8% in July–September, down from the +6.9% recorded in April–June (from here on, all figures refer to ‘same- period previous-year’ growth unless otherwise specified). -

2020 Annual Report Contents

2020 Annual Report Contents ABOUT US CORPORATE GOVERNANCE i Five-Year Summary 116 Corporate Governance Report 1 Introduction 131 Changes in the Share Capital and ’ 2 Business Performance at a Glance Shareholders Profile Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management 4 Chairman’s Statement 134 and Employees 152 Report of the Board of Directors and MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS Significant Events 170 Report of the Supervisory Committee 8 Customer Development 14 Technology-Powered Business Transformation FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 20 Business Analysis 20 Performance Overview 172 Independent Auditor’s Report 23 Life and Health Insurance Business 179 Consolidated Income Statement 32 Property and Casualty Insurance Business 180 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive 38 Investment Portfolio of Insurance Funds Income 181 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 44 Banking Business 183 Consolidated Statement of Changes In Equity 54 Asset Management Business 184 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 60 Technology Business 185 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 68 Analysis of Embedded Value 79 Liquidity and Capital Resources 85 Risk Management OTHER INFORMATION 100 Sustainability 327 Ping An Milestones 113 Prospects of Future Development 328 Honors and Awards 329 Glossary 332 Corporate Information Cautionary Statements Regarding Forward-Looking Statements To the extent any statements made in this Report contain information that is not historical, these statements are essentially forward- looking. These forward-looking statements include but are not limited to projections, targets, estimates and business plans that the Company expects or anticipates may or may not occur in the future. Words such as “potential”, “estimates”, “expects”, “anticipates”, “objective”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “will”, “may”, “should”, variations of these words and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. -

Central China Securities Co., Ltd

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Central China Securities Co., Ltd. (a joint stock company incorporated in 2002 in Henan Province, the People’s Republic of China with limited liability under the Chinese corporate name “中原證券股份有限公司” and carrying on business in Hong Kong as “中州證券”) (Stock Code: 01375) ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2017 The board (the “Board”) of directors (the “Directors”) of Central China Securities Co., Ltd. (the “Company”) hereby announces the audited annual results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 December 2017. This annual results announcement, containing the full text of the 2017 annual report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcements of annual results and have been reviewed by the audit committee of the Company. The printed version of the Company’s 2017 annual report will be dispatched to the shareholders of the Company and available for viewing on the website of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited at www.hkexnews.hk, the website of the Shanghai Stock Exchange at www.sse.com.cn and the website of the Company at www.ccnew.com around mid-April 2018. -

Annual Report

2018 Annual Report Annual Report HUA XIA BANK CO., LIMITED 2018 HUA XIA BANK CO., LIMITED HUA XIA BANK CO., Address: Hua Xia Bank Mansion, 22 Jianguomennei Street, Dongcheng District, Beijing Postal code: 100005 Tel: 010-85238570 010-85239938 Fax: 010-85239605 Website: www.hxb.com.cn CONTENTS 3 Message from Chairman for the Annual Report 2018 5 Message from President for the Annual Report 2018 6 Important Notice 7 Section I Definitions 8 Section II Company Profile and Major Financial Indicators 13 Section III Business Overview 16 Section IV Discussion and Analysis of Operations 53 Section V Significant Events 64 Section VI Details of Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders 74 Section VII Preference Shares 78 Section VIII Basic Information on Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management Members and Employees 89 Section IX Corporate Governance 94 Section X Financial Statements 95 Section XI List of Documents for Inspection 96 Written Confirmation of the Annual Report 2018 by Directors and Senior Management Members of Hua Xia Bank Co., Limited 98 Auditor’s Report 2018 Annual Report Hua Xia Bank Co., Limited Chairman of the Board: Li Minji 2 Message from Chairman for the Annual Report 2018 MESSAGE FROM CHAIRMAN FOR THE ANNUAL REPORT 2018 In 2018, China started to act on the guiding principles Hereby, I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to of the 19th CPC National Congress and celebrated the the public, shareholders, senior management and entire staff 40th anniversary of reform and opening-up, while Hua Xia on behalf of our Party Committee and the Board of Directors. -

Xi Jinping's Economic Policy in the Run-Up to the 19Th Party Congress

Xi Jinping’s Economic Policy in the Run-up to the 19th Party Congress: The Gift from Donald Trump Barry Naughton In the run-up to the 19th Party Congress in the fall of 2017, Xi Jinping has a strong interest in sustaining three narratives: the Chinese economy is growing stably, economic reform is moving forward, and a rising China is playing a more important role on the global scene. Xi has a good chance of sustaining all three of these narratives to his domestic audience, in part because of the valuable gift given him by the new U.S. president, Donald Trump. While we do not know the specific mental calculus being made by Xi Jinping, it is reasonable to assume that he is giving great attention to preparations for the 19th Party Congress, to be held in October or November of 2017. For Xi, there is much at stake. While his reelection as first party secretary is a foregone conclusion, the composition of the leadership group is still undetermined. According to the recently established norms of the Chinese Communist Party, only two of the seven current standing committee members—Xi himself and premier Li Keqiang—will continue on to the next standing committee. Whether Xi will respect the recent norms of leadership selection (per Alice Miller’s “three rules” for the selection of Standing Committee members) is not yet known.1 Without doubt, the choice of the other five members will determine the extent to which Xi succeeds in consolidating power and whether—if he chooses—Xi will be able to elevate his personal power above the institutional norms of the Communist Party. -

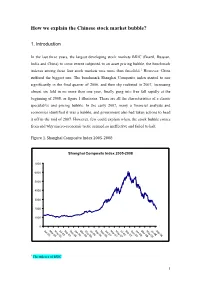

How We Explain the Chinese Stock Market Bubble?

1 However, China ese stock market bubble? pricing bubble, the benchmark oping stock markets BRIC (Brazil,cketed Russian, in 2007, increasing aracteristics of a classic ets rose more than threefold. tent subjected to an asset How we explain the Chin ment also had taken actions to head ly 2007, many a financial analysts and rter of 2006, and then sky ro 1. Introduction strates. These are all the ch ould explainso ineffective where th eand stock failed bubble to halt. comes In the last three years, the largest devel India and China) to some ex indexes among these four stock mark suffered the biggest one. The benchmark Shanghai Composite index started to rise significantly in the final qua almost six fold in no more than one year, finally gang into free fall rapidly at the beginning of 2008, as figure 1 illu speculative and pricing bubble. In the ear Sep‐08 economics identified it was a bubble, and govern Jul‐08 Shanghai Composite Index 2005-2008 May‐08 it off in the mid of 2007. However, few c Mar‐08 from and why macro-economic tactic seemed Jan‐08 Nov‐07 1 Sep‐07 Figure 1. Shanghai Composite Index 2005‐2008 Jul‐07 May‐07 Mar‐07 Jan‐07 7000 Nov‐06 Sep‐06 6000 Jul‐06 5000 May‐06 Mar‐06 4000 Jan‐06 Nov‐05 3000 Sep‐05 Jul‐05 2000 May‐05 Mar‐05 1000 0 Jan‐05 1 The indexes of BRIC Since the movement of stock prices is caused by the actions of investors, asset pricing bubbles ultimately have to be traced back to the beliefs of investors. -

Shenzhen Textile (Holdings) Co., Ltd. 2019 Annual Report March 2020

Shenzhen Textile (Holdings) Co., Ltd. 2019 Annual Report March 2020 I. Important Notice, Table of Contents and Definitions The Board of Directors , Supervisory Committee, All Directors, Supervisors and Senior executives of the Company hereby guarantees that there are no misstatement, misleading representation or important omissions in this report and shall assume joint and several liability for the authenticity, accuracy and completeness of the contents hereof. Mr.Zhu Jun, The Company leader, Mr. He Fei, Person in charge of accounting works, Ms. Mu Linying,the person in charge of the accounting department (the person in charge of the accounting )hereby confirm the authenticity and completeness of the financial report enclosed in this annual report. All the directors attended the board meeting for the review of this Report. I. Concerning the forward-looking statements with future planning involved in the Report, they do not constitute a substantial commitment for investors, investors should be cautious with investment risks . II. The company has the macroeconomic risks, market competition risks and raw material risks. Investors are advised to pay attention to investment risks. For details, please refer to the possible risk factors that the company may face in the “IX Prospects for the future development of the company" in the “Section IV Discussion and Analysis of Business Operation”. III. The company to remind the majority of investors,Securities Time, China Securities Journal, Securities Daily, Shanghai Securities News , Hongkong Commercial Daily and Juchao Website(http://www.cninfo.com.cn) are the media for information disclosure appointed by the Company, all information under the name of the Company disclosed on the above said media shall prevail, and investors are advised to exercise caution of investment risks. -

Annual Report 2010

Stock Code: 2628 Annual Report 2010 Annual Report 2010 The Company is a life insurance company established in Beijing, China on 30 June 2003 according to the Company Law of the People’s Republic of China. The Company was successfully listed on the New York Stock Exchange, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and the Shanghai Stock Exchange on 17 and 18 December 2003, and 9 January 2007, respectively. The Company’s registered capital is RMB28,264,705,000. The Company is the largest life insurance company in China’s life insurance market. Our distribution network, comprising exclusive agents, direct sales representatives, and dedicated and non-dedicated agencies, is the most extensive one in China. The Company is one of the largest institutional investors in China, and through its controlling shareholding in China Life Asset Management Company Limited, the Company is the largest insurance asset management company in China. The Company also has controlling shareholding in China Life Pension Company Limited. Our products and services include individual life insurance, group life insurance, accident and health insurance. The Company is a leading provider of individual and group life insurance, annuity products and accident and health insurance in China. As at the end of 31 December 2010, the Company had nearly 129 million individual and group life policies and annuities, and long-term health insurance policies in force. We also provide both individual and group accident and short-term health insurance policies and services. China Life Insurance Company -

Announcement of Results for the Year Ended December 31, 2020

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 6066) ANNOUNCEMENT OF RESULTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The board of directors of CSC Financial Co., Ltd. (the “Company”) hereby announces the consolidated results of the Group for the year ended December 31, 2020. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2020 annual report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcements of annual results. The printed version of the Company’s 2020 annual report will be dispatched to the shareholders of the Company and available for viewing on the website of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited at www.hkexnews.hk and the website of the Company at www.csc108.com by the end of April 2021. By order of the Board CSC Financial Co., Ltd. Wang Changqing Chairman Beijing, the PRC, March 31, 2021 As at the date of this announcement, the executive Directors of the Company are Mr. WANG Changqing and Mr. LI Geping; the non-executive Directors of the Company are Mr. -

方大集团股份有限公司 CHINA FANGDA GROUP CO., LTD. Semi

方大集团股份有限公司 CHINA FANGDA GROUP CO., LTD. Semi-Annual Report 2007 Important Statement The Board of Directors and the directors of the Company guarantee that there are no significant omissions, fictitious or misleading statements carried in the Report and we will accept individual and joint responsibilities for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the Report. This report has been examined and adopted by the 20th meeting of the 4th term of Board. Mr. Wen Simei, the independent director absent the meeting for business engagement, he entrusted independent director Zhen Xueding to exercise his right of voting and issued the independent opinions. The other directors all presented the meeting. The Financial Statement carried in the Semi-annual Report was not audited. Mr. Xiong Jianming, the Chairman of Board, and Mr. Lin Kebin, the Chief Financial Officer declare: the Financial Report carried in this report is authentic and completed. This report was prepared both in English and Chinese. Should there be any conflict in understanding, the Chinese version shall prevail. Definitions The following terms are defined to the companies goes after them unless otherwise stated. the Company : China Fangda Group Co., Ltd. The Group: the Company and its subsidiaries Fangda Decoration: Shenzhen Fangda Decoration Engineering Co., Ltd. Fangda Yide: Fangda Yide New Material Co., Ltd. Fangda Aluminium: Jiangxi Fangda New-type Aluminium Co., Ltd. Fangda Guoke: Shenzhen Fangda Guoke Electri-Optical Technical Co., Ltd. Fangda Automatic: Shenzhen Fangda Automatic System Co., Ltd. Fangda New Materials: Fangda New Materials (Jiangxi) Co., Ltd. HK Junjia: Hong Kong Junjia Group Co., Ltd. Banglin: Shenzhen Banglin Technology Development Co., Ltd. -

Radomir Tylecote

Ownership and Innovation in Chinese Solar Photovoltaic Firms: An Analysis of the Effects of State, Private, and Foreign Shareholding on Patenting Performance Radomir Tylecote Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives licence. Researchers are free to copy, distribute or transmit the thesis on the condition that they attribute it, that they do not use it for commercial purposes and that they do not alter, transform or build upon it. For any reuse or redistribution, researchers must make clear to others the licence terms of this work. 1 Abstract This thesis is a quantitative study of the effect of ownership – by state, private and foreign shareholdings – on innovation by China’s solar photovoltaic (PV) firms. Using the country’s solar PV industry, I seek to explain the impact of proportions of these different types of shareholding (and within the state category shareholding by central, provincial, and municipal governments) on innovative capacity. This capacity is measured by firms’ rates and qualities of patenting. As Chinese economic growth falters, amid the “re-shoring” of certain manufacturing capabilities, the role of the state, and whether it is helping or hindering its economy’s – and Chinese firms’ – technological upgrading, is a vital question. This is particularly true in high-tech sectors, including solar PV, which the Chinese government deems essential for the country’s continuing economic growth. Through the solar PV industry, we investigate the role of the state, and how it is helping or hindering Chinese companies’ innovation.