Of Lunchcounter and Soda Jerk Operatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restaurants, Owners, Locations, and Concepts

PART ONE Restaurants, Owners, Locations, and Concepts The Concept of B. Cafe´ B. Cafe´ is a Belgian-themed bistro offering a wide variety of beer and a cuisine that is a Belgian and American fusion. B. Cafehasthree´ owners, Skel Islamaj, John P. Rees, and Omer Ipek. Islamaj and Ipek are from Belgium, and Rees is Ameri- can. The owners felt that there was a niche in New York for a restaurant with a Belgian theme. Out of all the restaurants in New York, only one or two offered this type of concept, and they were doing well. Since two of the owners grew up in Belgium, they were familiar and comfortable with both Belgian food and beer. Today B. Cafe´ offers over 25 Bel- gian brand beers, and the list is growing. Courtesy of B. Cafe´ LOCATION B. Cafe´ is located on 75th Street in finding the right place. They came restaurant whose owner offered to New York City. The owners looked across the location after checking sell. According to owner Islamaj, for a location for two years before the area and finding a brand-new going with a building that held 2 ■ Part One Restaurants, Owners, Locations, and Concepts occupancy as a restaurant was ‘‘a and journalism community. Their ■ They cannot estimate their good way to control cost.’’ They preopening marketing consisted percentage of profit (it is 0 did some renovations and adapted of contacting old connections, percent so far), as the cafe´ what already existed. which landed them an article in a opened three weeks prior to newspaper. -

Nothing Could Be Finer Than a Garden State Diner

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Contact: PATRICK MURRAY This poll was conducted by the 732-263-5858 (office) Monmouth University Polling Institute 732-979-6769 (cell) [email protected] 400 Cedar Avenue West Long Branch, NJ 07764 For immediate release: www.monmouth.edu/polling Wednesday February 13, 2008 NOTHING COULD BE FINER THAN A GARDEN STATE DINER 2-in-3 New Jerseyans visit a diner monthly; Many prefer the flashier restaurant-style establishments What could be more Jersey than eating in a diner? They’re everywhere in the Garden State. And perhaps that’s why many of us slide into a booth at least once a month to order up a burger or omelet from a waitress who invariably calls us “Hun”. The latest Monmouth University/New Jersey Monthly Poll found that 29% of state residents eat out at a New Jersey diner at least once a week and another 38% visit a local diner one to three times a month. Another 23% visit one only occasionally and just 10% of New Jerseyans claim to have never set foot in a diner. Garden State men (73%) are somewhat more likely than women (60%) to be monthly patrons. There are some interesting regional differences in diner patronage. South Jerseyans are the state’s diner mavens – 78% of residents in the southern counties visit at least once a month, compared to 67% in North Jersey and 56% in Central Jersey. While diners tend to be thought of as breakfast or brunch establishments, most patrons say their favorite time of day to have a diner meal is in the evening. -

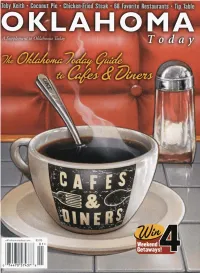

The Oklahoma Today Guide to Cafes & Diners

AMlRIcAN Around the Comer 11 S, Broadway 341-5414 Bennigan's 1150 E. 2nd 341-8860 Bunny's Onion Burgers 733 W. Danforth Rd. 216-9580 Deltsr C& 3301 S Boukvard 341-0400 .GoMieL Patio GiD 5 E 9th 348-1555 Henry Hudson's ?&2100 E. 2nd Street 359-6707 Hillbillee's Cafe 206 E. Highway 66 Arcadia, OK 396-2666 Home Plate Hot Dogs 122 East 2nd Street 340-2777 Jimmy's Egg 2621 & &adway 3110-6611 Jahnnie's Charcoal Broiler 33 E 33rd h t 348-3214 &B Spc~eGrin 70 112 E 15th Wt 715-9090 Plaza Grill 930 E. 2nd Street w-4722 ~AR-B-Q Cannon Bar-B-Q 2925 E. Waterloo Rd. 340-1161 Firehouse - vbegue 617 S. Bmadway 340-6107 Jby43&d'1555 S, Kelly 340-2144 - m'sRib 216 S. Santa Fe Avenue 340-7427 CHIMER Blue Moon Chinese 1320 S. g'-dway 340-3871 Caf6 De Taipei 603 S. Broadway 216-9968 China Stat 1601 S. ,adway 348-2788 China Wok 1315 E. Danforth 341-2329 Dot Wo Chinese Seahod 64E. 33rd 341-2878 Hunan House 2nd & Santa Fe 330-1668 Mandarin Express 511 S. Broadway 341-8337 Marbo Chinese 1708 E. 2nd Street 341-8816 Panda House Chinese 1803 S. Broadway 348-6300 W o Chinme 16317 N,Santa kAm 359-2012 CDNTINENTAL Wt! 501501 S. &dd 359-1501 Panera Bread 1472 S. Bryant Ave. 844-5525 DELI Cafe Broadway 108 South Broadway 348-7887 Coyote Coffee Co. 1710E. 2nd Street 359-2293 Founrain Oaks Station 201 Meline Dr. 33Q-5101 Hobby's Hoagies 222 S. -

Lafayette Restaurant Guide

An Opinionated Resident’s Guide to Food and Miscellaneous Other Items in Lafayette, West Lafayette and Environs By Kay Widdows July 2013 Food and Drink. Note: there has been a veritable explosion of new restaurants and bars in Lafayette and West Lafayette in the last couple of years. New places are being added all the time, so not being on the list might just mean that a place is new – not that it’s not worth checking out. Pubs/Pub Food/Breweries The Black Sparrow – (765) 429-0405, 223 Main Street, Downtown Lafayette. Primarily a bar and a music venue but food is served (tapas-style appetizers, pizza, salads). Comprises two nicely restored rooms in an historic building. Casual. Bar features a very good selection of regional microbrewery beers, usually about six or seven taps that alternate. Menu selections are creative; the goat cheese and fig pizza is great. Managed by the spouse of Kate, a manager at the LBC. Good people. Chumley’s - (765) 420-9372, 122 N 3rd St., Lafayette Sports-type bar downtown with huge beer selection (50 beers on tap including 3 Floyds, Peoples, Goose Island) and so-so food. Very crowded Thursday nights, and very loud after about 9 PM. Lafayette Brewing Company – (765) 742-2591, 622 Main St., Downtown Lafayette. Pub food including burgers, salads, sandwiches and dinner specials. Beer selections change frequently and there’s always a lot of choice. Recent IPA’s have been outstanding. Sandwiches around 6-7 dollars, entrées in the 10-12 dollar range. Staff will customize entrées if you ask them. -

Soft Drink from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Soft drink From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A glass of cola served with ice cubes A soft drink (also called soda, pop, coke,[1] soda pop, fizzy drink, seltzer, mineral,[2] lolly water[3] or carbonated beverage) is abeverage that typically contains carbonated water, a sweetener and a flavoring. The sweetener may be sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, fruit juice, sugar substitutes (in the case of diet drinks) or some combination of these. Soft drinks may also contain caffeine, colorings, preservatives and other ingredients. Soft drinks are called "soft" in contrast to "hard drinks" (alcoholic beverages). Small amounts of alcohol may be present in a soft drink, but the alcohol content must be less than 0.5% of the total volume[4][5] if the drink is to be considered non-alcoholic.[6] Fruit juice, tea and other such non- alcoholic beverages are technically soft drinks by this definition but are not generally referred to as such. Soft drinks may be served chilled or at room temperature, and some, such as Dr Pepper, can be served warm.[7] Contents [hide] 1 History o 1.1 Carbonated drinks o 1.2 Soda fountain pioneers o 1.3 Soda fountains vs. bottled sodas o 1.4 Soft drink bottling industry . 1.4.1 Automatic production of glass bottles . 1.4.2 Home-Paks and vending machines 2 Production o 2.1 Soft drink production o 2.2 Ingredient quality . 2.2.1 Potential alcohol content 3 Producers 4 Health concerns o 4.1 Obesity and weight-related diseases o 4.2 Dental decay o 4.3 Hypokalemia o 4.4 Soft drinks related to bone density and bone loss o 4.5 Sugar content o 4.6 Benzene o 4.7 Pesticides in India o 4.8 Kidney stones 5 Government regulation o 5.1 Schools o 5.2 Taxation o 5.3 Bans 6 See also 7 References 8 External links History[edit] This section needs additional citations for verification. -

Retrospect Peter Szende and Heather Rule Thompson's Spa: the Most Famous Lunch Counter in the World

Retrospect Employees (1928) Thompson’s Spa: The Most Famous Lunch Counter in the World Peter Szende and Heather Rule The legacy of Charles Eaton began with a little of mineral water, which had been pioneered in the bit of luck. In 1882, while walking along Washing- Belgian town of Spa and then popularized in Amer- ton Street in downtown Boston, he passed a vacant ican resorts such as Saratoga Springs, New York. building that seemed to be a good site for a new By 1895, there were more than 100,000 soda business serving non-alcoholic beverages. In short fountains in the nation, and the soft-drink empires order, he emerged with the lease. As an ironic twist, of Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola were rapidly emerg- his new ‘temperance saloon’ would be located on ing. The Bulletin of Pharmacy declared soda “the the former site of the first tavern in Boston, which great American drink.” Charles Eaton recognized had been licensed to Samuel Cole in 1633. this movement early and capitalized on it. His idea The naming of Thompson’s Spa was deliberate. of a non-alcoholic bar was immediately successful Eaton wanted to avoid the obvious joke his last name and the company began to turn a profit after only might incur as a restaurant, so he decided to use six months. Although beverages eventually became his wife’s maiden name, Thompson. He also hoped a secondary product, they remained a significant to invoke the idea of the health restoring qualities part of the business, with soda drinks alone gener- Fall 2012 | Boston Hospitality Review 33 ating over $50,000 annually during the early years. -

The One & Only* Smoked Goat Burger* Poppin' Jalapeño

THE ONE & ONLY* STUFFED AVOCADO Our beef burger topped with aged white cheddar Grilled avocado half stuffed with chorizo, queso dip, pimento cheese, bacon and caramelized onions ...............$11.95 and pico de gallo, served with fried tortilla chips .................. $7.95 (Flour or Corn Chips Available) SMOKED GOAT BURGER* NACHOS Our beef burger topped with smoked Corn chips, chorizo, queso, pico de gallo, goat cheese, bacon and a pepper jelly ............................. $12.95 fresh jalapeños, black beans, * chipotle-lime sour cream and scallions ...............................$9.95 POPPIN’ JALAPEÑO Our beef burger topped with jalapeño bacon, ELOTES house-made ranch, pepper-jack cheese, and a jalapeño and cream cheese fritter .......................... $12.95 Roasted corn on the cob brushed with mayo, rolled in cotija cheese, and dusted in cayenne-paprika ........$4.95 GREASY SPOON* CHIPS & DIP Our beef burger topped with American cheese, sliced onion, tomato, lettuce, pickles and house sauce .........................$11.95 Choose one of the following: Pico ...................................................................................$3.95 * Guacamole or Queso ..........................................................$5.95 BIG TRUCK Queso with Chorizo .............................................................$6.95 Our beef burger topped with pimento mac and cheese, bacon BBQ sauce, (Flour or Corn Chips Available) bacon, tobacco onions and scallions ............................... $12.95 DIRTY SOUTH NACHOS * Sweet potato -

Spice Level Especially If You Have Certain Medical Conditions

THE ONE & ONLY* STUFFED AVOCADO Beef burger topped with aged white cheddar Grilled avocado half stuffed with chorizo, queso dip, pimento cheese, bacon and caramelized onions ...............$11.95 and pico de gallo, served with fried tortilla chips .................. $7.95 (Flour or Corn Chips Available) SMOKED GOAT BURGER* NACHOS Beef burger topped with smoked Corn chips, chorizo, queso, pico de gallo, goat cheese, bacon and a pepper jelly ............................. $12.95 fresh jalapeños, black beans, * chipotle-lime sour cream and scallions ...............................$9.95 POPPIN’ JALAPEÑO Beef burger topped with jalapeño bacon, ELOTES house-made ranch, pepper-jack cheese, fresh jalapeño and a jalapeño and cream cheese fritter .......................... $12.95 Roasted corn on the cob brushed with mayo, rolled in cotija cheese, and dusted in cayenne-paprika ........$4.95 GREASY SPOON* CHIPS & DIP Beef burger topped with American cheese, sliced onion, tomato, lettuce, pickles and house sauce .........................$11.95 Choose one of the following: Pico ...................................................................................$3.95 * Guacamole or Queso ..........................................................$5.95 BIG TRUCK Queso with Chorizo .............................................................$6.95 Beef burger topped with pimento mac and cheese, bacon BBQ sauce, (Flour or Corn Chips Available) bacon, tobacco onions and scallions ............................... $12.95 DIRTY SOUTH NACHOS * Sweet potato chips -

English As a Second Language Podcast ESL Podcast 618 – Eating

English as a Second Language Podcast www.eslpod.com ESL Podcast 618 – Eating at a Casual Restaurant GLOSSARY something the matter with – a problem or issue with something; something that isn’t right or correct * Is something the matter with your leg? You’re walking strangely. how to put this – a phrase used when one is uncomfortable because one wants to say something that might hurt another person’s feelings or be awkward * I don’t know how to put this, but you should know that you don’t look very good when you wear orange or yellow colors. diner – a restaurant that serves informal, inexpensive meals * This diner serves great fried chicken and mashed potatoes. hole in the wall – a business, restaurant, or store that doesn’t look very nice and is not fancy * I know this place looks like a hole in the wall, but it has very good service. mom and pop – referring to a small business owned by a married couple or a small family * As a teenager, Ross spent each summer working in a mom and pop grocery store down the street from his house. it’s the (something) that counts – a phrase used to show that one particular thing is what really matters or what is really important, and nothing else is as important as that one thing * It’s too bad you didn’t like his gift, but it’s the thought that counts. Wasn’t it a nice surprise that he remembered your birthday? ambiance – environment; the way that a place looks and how it feels to be there * We could improve the store’s ambiance by changing the lighting and hanging some plants from the ceiling. -

The 2017 Beverage Marketing Directory Copyright Notice

About this demo This demonstration copy of The Beverage Marketing Directory – PDF format is designed to provide an idea of the types and depth of information and features available to you in the full version as well as to give you a feel for navigating through The Directory in this electronic format. Be sure to visit the Features section and use the bookmarks to click through the various sections and of the PDF edition. What the PDF version offers: The PDF version of The Beverage Marketing Directory was designed to look like the traditional print volume, but offer greater electronic functionality. Among its features: · easy electronic navigation via linked bookmarks · the ability to search for a company · ability to visit company websites · send an e-mail by clicking on the link if one is provided Features and functionality are described in greater detail later in this demo. Before you purchase: Please note: The Beverage Marketing Directory in PDF format is NOT a database. You cannot manipulate or add to the information or download company records into spreadsheets, contact management systems or database programs. If you require a database, Beverage Marketing does offer them. Please see www.bmcdirectory.com where you can download a custom database in a format that meets your needs or contact Andrew Standardi at 800-332-6222 ext. 252 or 740-314-8380 ext. 252 for more information. For information on other Beverage Marketing products or services, see our website at www.beveragemarketing.com The 2017 Beverage Marketing Directory Copyright Notice: The information contained in this Directory was extensively researched, edited and verified. -

Keedy's Breakfast Special

BREAKFAST (SERVED ALL DAY) LUNCHEONS ONE EGG ANY STYLE .....................................................................................6.55 WITH BACON, SAUSAGE LINK OR HAM ................................................8.75 HAMBURGERS COUNTRY FRIED STEAK .............................................................................. 13.90 WITH CORNED BEEF HASH OR SAUSAGE PATTY ................................9.80 (Known as a “Keedy’s Fix”) FRIED CHICKEN ............................................................................................. 13.40 TWO EGGS ANY STYLE ..................................................................................7.85 (SERVED WITH MAYONNAISE, RELISH, LETTUCE, ONION & TOMATO & POTATO CHIPS) STEAK SANDWICH (CHOICE RIB EYE) ..................................................... 14.95 WITH BACON, SAUSAGE LINK OR HAM .............................................10.80 SPLIT SANDWICHES AND BASKET $1.25 EXTRA PORK CHOPS ................................................................................................... 13.95 HAMBURGER ........................................................................................... 7.95 WITH CORNED BEEF HASH OR SAUSAGE PATTY ..............................10.80 FISH AND CHIPS ............................................................................................. 12.85 CHEESEBURGER ..................................................................................... 8.30 DICED HAM AND EGGS ................................................................................10.80 -

Fix the Pumps

Copyright Copyright © 2009 by Darcy S. O’Neil. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passage for purpose of reviews) without the prior permission of Darcy S. O’Neil. Written and Designed by Darcy S. O’Neil Cover Art by Craig Mrusek ISBN-13: 978-9-81175-904-8 Designed with Corel Ventura Darse Diggity Dog Publication 19 Appel Street London, Ontario, Canada N5Y 1R1 email: [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction. 1 Serving Egg Drinks. 68 How It All Got Started. 4 Soda Acidulants. 74 Soda Controversy. 9 Acid Phosphates . 74 Soda Replaces the Cocktail. 12 Lactic Acid . 79 Soda Health & Hygiene. 14 Citric and Tartaric Acid . 80 Pop vs Soda . 17 Vinegar. 81 The Soda Jerk. 18 Druggists’ Sundries . 82 From Bartender to Soda Jerk . 20 Aromatic Elixir . 85 Talk Like a Soda Jerk . 23 Aromatic Spirit of Ammonia. 86 Types of Soda . 27 Elixir of Calisaya . 87 Ice Drinks . 28 Colouring . 88 Mead & Root Beer. 29 Notes on Ingredients. 90 Ginger Ale . 30 The Last Gulp. 96 Lemon Soda . 32 Soda’s Influence on the Cocktail . 97 Cream Soda . 32 Wanted: Soda Jerks . 101 Crush . 33 Recipe Conventions. 103 Chocolate Soda . 34 Fountain Recipes . 103 Phosphates. 35 Extracts & Essences . 104 Cola . 36 Lactarts . 40 Syrup & Drink Recipes . 113 Hot Soda . 40 Base Syrups . 114 Egg Drinks . 41 Compound Syrups . 120 Milkshakes . 43 Phosphate Syrups. 125 Malts . 44 Lactart Syrups .