Full Transcript of the Archbishop's Presidential 2018 Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SA Police Gazette 1947

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently The resolution of this sampler has been reduced from the original on CD to keep the file smaller for download. South Australian Police Gazette 1947 Ref. AU5103-1947 ISBN: 978 1 921494 86 4 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by the South Australia Police Historical Society www.sapolicehistory.org Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

SA Police Gazette 1937

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently The resolution of this sampler has been reduced from the original on CD to keep the file smaller for download. South Australian Police Gazette 1937 Ref. AU5103-1937 ISBN: 978 1 921494 27 7 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by the South Australia Police Historical Society www.sapolicehistory.org Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

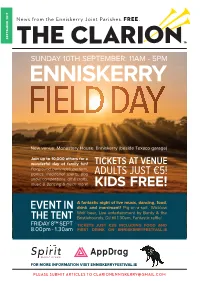

Pig-On-A-Spit, Wicklow Wolf Beer, Live Entertainment By

FREE september 2017 16 A fantastic night of live music, dancing, food, drink and merriment! Pig-on-a-spit, Wicklow Wolf beer, Live entertainment by Bunty & the Bristlehounds, DJ till 1.30am, Fantastic raffle! PLEASE SUBMIT ARTICLES TO [email protected] Powerscourt & Kilbride News Dear All, KILBRIDE NOTES The summer has flown by as usual and though Thank you to everyone who supported the “Strawberries & many people have been away on holiday etc Cream” event in the Rectory Marquee on the 9th July. This event there has been quite a bit of activity. Much of it was a great success. Many thanks to everyone who helped, those has centred around the parish marquee which is who donated raffle prizes and those who donated the strawberries erected at the start of summer each year in the and the cream. Rectory grounds. The marquee is used every Sunday for coffee after church in Powerscourt but is also the The next meeting of Kilbride Parish Select Vestry will be on 13th venue for a number of special events. September 2017. Kilbride Harvest Festival will be on Sunday, 2nd October at 10.00 am and the preacher will be Canon George On 9th July Kilbride Parish used it for a most enjoyable ‘strawberries Butler. Refreshments will follow in the Parish Room. The Church and cream’ fundraiser. The parish BBQ was held there on 15th will be decorated on Saturday 1st October at 10 am and fruit, July and a special reception following the baptism of Olive Mary vegetables and flowers would be gratefully received then. -

Patrick Comerford MU 130Th Anniversary P.17 – the Anglican Reformation P.19

JULY / AUGUST 2017 NEWSLINK The Magazine of the Church of Ireland United Dioceses of Limerick, Killaloe & Ardfert INSIDE Patrick Comerford MU 130th Anniversary p.17 – The Anglican Reformation p.19 GFS 140th Anniversary p.18 Tralee welcomes Rev Jim Stephens p.20 Key figures in the story of the Anglican Reformation depicted in a window in Trinity College, Cambridge, How can I keep from singing? p.2 from left (above): Hugh Latimer, Edward VI, Nicholas Ridley, Elizabeth I; (below): John Wycliffe, Erasmus, William Tyndale and Thomas Cranmer Bishop Kenneth writes p.3 Prayer Corner p.5 View from the Pew p.6 Archbishop Donald Caird p.6 Weddings are changing p.16 If the World were a Village p.33 Children’s Page p.38 including Methodist District News p. 32 1 ISSN. 0790-4517 www.limerick.anglican.org How can I keep from singing? by the Rev. Canon Liz Beasley ‘My life flows on in endless song, above earth’s lamentation, I hear the real, though far-off hymn that hails a new creation. Through all the tumult and the strife, I hear the music ringing; it finds an echo in my soul. How can I keep from singing?’ This is the first verse and chorus discovered that singing together at the Rectory has benefits beyond of hymn 103 in the Church of the merely practical ones of learning new hymns. We all feel better Ireland’s new hymnal, Thanks & after spending just an hour singing together. Singing lifts our spirits. Praise. It is also one of the hymns We have joined with one another in lifting our voices to God. -

20200214 Paul Loughlin Volume Two 2000 Hrs.Pdf

DEBATING CONTRACEPTION, ABORTION AND DIVORCE IN AN ERA OF CONTROVERSY AND CHANGE: NEW AGENDAS AND RTÉ RADIO AND TELEVISION PROGRAMMES 1968‐2018 VOLUME TWO: APPENDICES Paul Loughlin, M. Phil. (Dub) A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Professor Eunan O’Halpin Contents Appendix One: Methodology. Construction of Base Catalogue ........................................ 3 Catalogue ....................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. BASE PROGRAMME CATALOGUE CONSTRUCTION USING MEDIAWEB ...................................... 148 1.2. EXTRACT - MASTER LIST 3 LAST REVIEWED 22/11/2018. 17:15H ...................................... 149 1.3. EXAMPLES OF MEDIAWEB ENTRIES .................................................................................. 150 1.4. CONSTRUCTION OF A TIMELINE ........................................................................................ 155 1.5. RTÉ TRANSITION TO DIGITISATION ................................................................................... 157 1.6. DETAILS OF METHODOLOGY AS IN THE PREPARATION OF THIS THESIS PRE-DIGITISATION ............. 159 1.7. CITATION ..................................................................................................................... 159 Appendix Two: ‘Abortion Stories’ from the RTÉ DriveTime Series ................................ 166 2.1. ANNA’S STORY ............................................................................................................. -

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin MS 438 Miscellaneous

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin MS 438 Miscellaneous correspondence, speeches, papers and photographs of J.L.B. Deane (d.2012) rel. mainly to his contributions to the work of the General Synod and the Standing Committee, Pensions Board, Board of Education, Role of the Church Committee, Representative Church Body, and the Cork, Cloyne and Ross Diocesan Synod 1958-2014 From Canon J.L.B. Deane, Bandon, Co. Cork and his executors 1. Correspondence, speeches and papers 1-2. 25 January 1958 Two legal opinions obtained by J.L.B.D. from V.T.H. Delany, Faculty of Law, Queen's University, Belfast, rel. to the marriage of minors (5 ff, TS). 2a. 7 Feb. 1958 Letter from [Maj.] Charles Roberts, Treanlaur, Newport, Co. Mayo rel. to diocesan views in Tuam, Killala & Achonry about the possible election of a new bishop. 3. 16 May 1959 Letter from Sir Cecil Stafford King-Harman rel. to a bill in the General Synod to establish episcopal electoral colleges. 4-5. 24 & 28 Sept. Two letters from Charles Tyndall, Bishop of Derry, 1960 suggesting the centralising of church records and the revision of the official history of the Church of Ireland in preparation for celebrating the centenary of disestablishment. 6. 1962 Speech at the General Synod introducing the report of the Representative Church Body (13 ff, TS + explanatory MS note). 7-9. 1963 Three speeches on the Anglican Congress, Toronto (3ff, 10ff, 5 ff, TS) 10-12. 1, 3 & Oct. Correspondence with James McCann, Archbishop of 1963 Armagh, and Maurice Dobbin rel. to consideration by the Church of Ireland of "Mutual Responsibility and Interdependence in the Body of Christ", a document from the Toronto Congress, together with an explanatory note from J.L.B.D. -

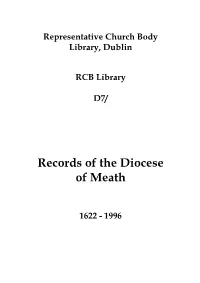

Records of the Diocese of Meath

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin RCB Library D7/ Records of the Diocese of Meath 1622 - 1996 2 MAIN RECORD GROUPS 1. Visitations and Rural Deanery Reports (1817-1977) 3 2. Records Relating to Bishops of Meath (1804-1995) 8 3. Records Relating to the Diocesan Clergy and Lay Readers (1850-1985) 12 4. Diocesan Synod Records (1870-1958) 15 5. Diocesan Council Records (1870-1970) 17 6. Maps and Plans (1692-20 th century) 20 7. Records Relating to Glebe Lands (1811-1905) 22 8. Legal Papers (1835-1940) 23 9. Accounts (1875-1976) 24 10. Papers of Individual Parishes (18 th century-20 th century) 26 11. Papers Relating to General Parochial Organisation (1870-1980) 35 12. Miscellaneous Diocesan Registry Papers (1686-1991) 38 13. Papers Relating to Diocesan Education (1866-1996) 49 14. Papers Relating to Diocesan Charities and Endowments (1811-1984) 55 15. Seals and Related Papers (1842-1978) 59 16. Photographs (19 th and 20 th century) 61 17. Diocesan Magazines (1885- 1974) 63 18. Copies, Notes and Extracts From Diocesan Records and Other Sources (17 th century-20 th century) 65 19. Papers of Canon John Healy 67 3 1/ Visitations and Rural Deanery Reports The visitations in the Meath diocesan collection are mostly from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, having survived in the diocesan registry after many others were transferred to the Public Record Office of Ireland (and not, therefore, destroyed in 1922). However the collection also includes one seventeenth-century return (D7/1/1A). As a result of the cataloguing process on the diocesan material carried out in the RCB Library, it was discovered to be in Marsh's Library, Dublin, where it had been transferred for safe keeping until reclaimed. -

Adelaide Hospital Annual Report for the Year Ended 31St December 1989

Adelaide Hospital annual report for the year ended 31st December 1989. the 150th year of the hospital. Item Type Report Authors Adelaide Hospital. Citation Adelaide Hospital. 1990. Adelaide Hospital annual report for the year ended 31st December 1989. the 150th year of the hospital. Dublin: Adelaide Hospital. Publisher Adelaide Hospital. Download date 25/09/2021 19:40:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10147/559491 Find this and similar works at - http://www.lenus.ie/hse Adelaide Hospital Annual Report 1989 , • I' 1\ (' '.1 , ~ I , I ~ ", , ~, ,. ~\ I • ADELAIDE HOSPITAL (INCORPORATED) PETER STREET, DUBLIN. 8 ANNUAL REPORT For the year ended 31st December, 1989 (The One·Hundred·and·Fiftieth Year at the Hospital) No/ice is hereby given that the SEVENTIETH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING will be held in the Board Room on TUESDAY, 8th MAY, 1990a13.45 p.m. /0 transact the following business: 1. Honorary Secretary to present the Board of. Management Report and Audited Accounts tor the year ended 31st December, 1989. 2. Election of Honorary Officers for ensuing twelve' months: President: Mr. R. Ian Morrison Vice·Presidents: The Right Hon. the Earl of Iveagh Dr. David M. Mitchell Mrs. H. R. Blakeney Mrs. B. Somerville· Large Mr. Vernon D. Harty Mrs. R. E. Boothman Mr. Basil E. Booth Mr. R. E. Fenelon Honorary Treasurer: Mr. R. D. Burry Honorary Secretaries: Dr. Ian M. Graham Mr. Ross Hinds 3; Re·election of Auditors. 4. Vote of thanks to all the staff and helpers of the hospital. ':As we have therefore opportunity, let us do good unto all men, especially unto them who are of the househofd of faith." Gaf, vi 10. -

301147 Autumn Newsletter 30/10/2014 13:36 Page 1

301147 Autumn Cover 30/10/2014 10:54 Page 1 Friends’ News Christ Church Cathedral Dublin ISSN 0791-2331 Vol. 32 No. 2 Autumn 2014 ¤3 301147 Autumn Cover 30/10/2014 10:54 Page 2 Friends’ News Christ Church Cathedral is published by The Friends of Christ Church Cathedral, The Chapter House, Christchurch Place, Dublin 8 The opinions expressed in this journal are those of the authors and need not represent the views of the Friends of Christ Church Cathedral. The Friends of Christ Church Cathedral support the work and worship of the cathedral. Membership is open to all Patron: Archbishop of Dublin: The Most Revd Dr Michael Jackson Chairperson: Dean of Christ Church: The Very Revd Dermot Dunne Vice-chairpersons: Residential Priest Vicar: The Revd Garth Bunting Archdeacon of Dublin: The Ven David Pierpoint Archdeacon of Glendalough: The Ven Ricky Rountree Honorary secretary: Kenneth Milne Honorary treasurer: David Bockett Honorary membership secretary: Patricia Sweetman and Eileen Kennedy Honorary editor: Lesley Rue Committee members: Brian Bradshaw Desmond Campbell Valerie Houlden Eileen Kennedy Ruth Kinsella Don Macaulay Patricia Sweetman Terence Read David Wynne Friends’ Office: Lesley Rue: 087 790 6062 [email protected] Membership applications to The Hon. Membership Secretary The Chapter House Christ Church Cathedral Christchurch Place Dublin 8 Minimum subscriptions: Within Ireland – ¤20 or Overseas – $35 Contributions of ¤250 and over may be tax refundable in Ireland and include five year membership of the Friends Friends are invited to give more if they can E-mail: [email protected] front cover: Portrait of Dean Des Harman, Sue Harman, (and her grandson), Olivia Bartlett (artist) with Dean Dermot Dunne. -

Churchof England

THE ORIGINAL CHURCH NEWSPAPER. ESTABLISHED IN 1828 Celebrating all THE Analysis things organic in of a September, p8 CHU RCHOF parish mission, ENGLAND p10 Newspaper NOW AVAILABLE ON NEWSSTAND FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 No: 6246 Calls for reconciliation as Scots vote ‘No’ CHURCH LEADERS issued statements this morning calling Alex Salmond for reconciliation after the No and below campaigners won the Scottish 5am News David Cameron independence referendum by a disappointing to many, will be this morning margin of 55 per cent to 45 per welcomed by all those who cent. believe that this country can In upbeat remarks SNP leader continue to be an example of Alex Salmond said he accepted how different nations can work the verdict and called on all together for the common good Scottish people to ‘follow suit in within one state.” accepting the democratic ver - Archbishop Justin Welby dict of the people of Scotland’. added: “This is a moment for Prime Minister David reconciliation and healing not Cameron said he was ‘delighted’ rejoicing or recrimination. with the result. “As I said during Some of the wounds opened up the campaign, it would have in recent months are likely to broken my heart to see our take time to heal on both sides United Kingdom come to an of the border.” end.” He said the close links He said it was now time for between the Church of Scot - the United Kingdom to come land, the Scottish Episcopal together and move forward, but Church and the Church of Eng - added that a vital part of that land meant they all have a con - would be a balanced settlement: tribution to make “not only to “Fair to people in Scotland and reflect on the lessons of the ref - importantly to everyone in Eng - erendum campaign but to land, Wales and Northern Ire - engage in delivering the radical land as well.” restructuring of the relationship He said that the matter had between Scotland and the rest now been settled for a genera - of the United Kingdom for tion, or perhaps for a lifetime. -

CNI News - July 28

CNI News - July 28 The essential brief on the Irish churches Dr Donald Caird is presented with a copy of his autobiography by the author, Aonghus Dwane. Also pictured is Nancy Caird. Biography of Archbishop Dr Donald Caird launched The former Archbishop of Dublin, Donald Caird, is the subject of a new biography which was launched in Christ Church Cathedral On Saturday evening. The launch took place in the context of the centenary celebrations of Cumann Gaelach na hEaglaise, the Irish Guild of the Church. The biography, titled Donald Caird: Church of Ireland Bishop: Gaelic Churchman: a Life and published by Columba Press, was launched by Mrs Justice Catherine Page 1 CNI News - July 28 McGuinness who described as “both scholarly and accessible”. The large crowd in attendance included Dr Caird and his wife Nancy who received a very warm welcome. He was presented with a copy of his biography by the author, Aonghus Dwane. Also present was the Archbishop of Armagh, the Most Revd Dr Richard At the launch of the new biography of Dr Donald Caird are Clarke and Dean Dermot Dunne, Aonghus Dwane (author), Mrs Justice another former Catherine McGuinness and Dáithí Ó Maolchoille. Archbishop of Dublin, Dr Walton Empey. This biography explores Dr Caird’s career from the earliest days. As Bishop of Limerick, Bishop of Meath and Kildare, and Archbishop of Dublin successively, Dr Caird enjoyed a distinguished career in the Church of Ireland. His lifelong interests in the Irish language and ecumenism mean he is well–known in wider Irish society. His time in office, particularly as Archbishop of Dublin in the mid–1980s to mid–1990s coincided with historic developments in the life of both Church and State, including the great “liberal agenda” debates on contraception, abortion and divorce in the Republic; the ordination of women to the priesthood in the Church of Ireland, and the developing peace process in Northern Ireland. -

Representative Church Body

CHURCH OF IRELAND THE REPRESENTATIVE CHURCH BODY REPORT 2020 The Representative Church Body – Report 2020 CONTENTS Page Representative Body – chairpersons and offices 5 Representative Body – membership 6 Committees of the Representative Body 8 Report on the year 2019 13 Financial and operational review 2019 20 Allocations budget provided for 2020 26 Investments and markets 30 Clergy remuneration and benefits 34 Clergy pensions 38 Property and trusts 39 Library and archives 44 Donations and bequests to the Church of Ireland 50 Miscellaneous and general 53 Resolutions recommended to the General Synod 54 Financial statements year ended 31 December 2019 55 APPENDICES Page A Extracts from the accounts of the Church of Ireland Theological 85 Institute for the year ended 30 June 2019 B Annualised fund performances – comparative total returns 87 C General Unit Trusts – financial statements and extracts from investment 88 manager’s reports for the six months ended 31 December 2019 D Environmental, Social and Governance Policy – integrating ESG into 99 investment decisions 2020 E RCB Climate Change Policy 2020 101 F The Church of Ireland Clergy Defined Contribution Pension Schemes 103 (NI and RI) – reports of the scheme trustees G The Church of Ireland Clergy Pensions Trustee DAC – report on the 105 Clergy Pensions Fund for the year ended 31 December 2019 H The Church of Ireland Pensions Board – funds administered by the 147 Board as delegated by the Representative Church Body I Archive of the Month 2019 155 J Accessions of archives and manuscripts