30-Lockley (Otozoum)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oldest Known Dinosaurian Nesting Site and Reproductive Biology of the Early Jurassic Sauropodomorph Massospondylus

Oldest known dinosaurian nesting site and reproductive biology of the Early Jurassic sauropodomorph Massospondylus Robert R. Reisza,1, David C. Evansb, Eric M. Robertsc, Hans-Dieter Suesd, and Adam M. Yatese aDepartment of Biology, University of Toronto Mississauga, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6, Canada; bRoyal Ontario Museum, Toronto, ON M5S 2C6, Canada; cSchool of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, 4811 QLD, Australia; dDepartment of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013; and eBernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research, University of the Witwatersrand, Wits 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa Edited by Steven M. Stanley, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, and approved December 16, 2011 (received for review June 10, 2011) The extensive Early Jurassic continental strata of southern Africa clutches and recognition of the earliest known dinosaurian nesting have yielded an exceptional record of dinosaurs that includes complex at the Rooidraai locality. scores of partial to complete skeletons of the sauropodomorph Massospondylus, ranging from embryos to large adults. In 1976 an Results incomplete egg clutch including in ovo embryos of this dinosaur, Our work at the Rooidraai locality has yielded multiple in situ the oldest known example in the fossil record, was collected from clutches of eggs as well as fragmentary eggshell and bones, all from a road-cut talus, but its exact provenance was uncertain. An exca- a 2-m-thick interval of muddy siltstone 25 m from the top of the vation program at the site started in 2006 has yielded multiple in Lower Jurassic Upper Elliot Formation (“Stormberg Group,” situ egg clutches, documenting the oldest known dinosaurian Karoo Supergroup) (11). -

Download the Article

A couple of partially-feathered creatures about the The Outside Story size of a turkey pop out of a stand of ferns. By the water you spot a flock of bigger animals, lean and predatory, catching fish. And then an even bigger pair of animals, each longer than a car, with ostentatious crests on their heads, stalk out of the heat haze. The fish-catchers dart aside, but the new pair have just come to drink. We can only speculate what a walk through Jurassic New England would be like, but the fossil record leaves many hints. According to Matthew Inabinett, one of the Beneski Museum of Natural History’s senior docents and a student of vertebrate paleontology, dinosaur footprints found in the sedimentary rock of the Connecticut Valley reveal much about these animals and their environment. At the time, the land that we know as New England was further south, close to where Cuba is now. A system of rift basins that cradled lakes ran right through our region, from North Carolina to Nova Scotia. As reliable sources of water, with plants for the herbivores and fish for the carnivores, the lakes would have been havens of life. While most of the fossil footprints found in New England so far are in the lower Connecticut Valley, Dinosaur Tracks they provide a window into a world that extended throughout the region. According to Inabinett, the By: Rachel Marie Sargent tracks generally fall into four groupings. He explained that these names are for the tracks, not Imagine taking a walk through a part of New the dinosaurs that made them, since, “it’s very England you’ve never seen—how it was 190 million difficult, if not impossible, to match a footprint to a years ago. -

The Origin and Early Evolution of Dinosaurs

Biol. Rev. (2010), 85, pp. 55–110. 55 doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00094.x The origin and early evolution of dinosaurs Max C. Langer1∗,MartinD.Ezcurra2, Jonathas S. Bittencourt1 and Fernando E. Novas2,3 1Departamento de Biologia, FFCLRP, Universidade de S˜ao Paulo; Av. Bandeirantes 3900, Ribeir˜ao Preto-SP, Brazil 2Laboratorio de Anatomia Comparada y Evoluci´on de los Vertebrados, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘‘Bernardino Rivadavia’’, Avda. Angel Gallardo 470, Cdad. de Buenos Aires, Argentina 3CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cient´ıficas y T´ecnicas); Avda. Rivadavia 1917 - Cdad. de Buenos Aires, Argentina (Received 28 November 2008; revised 09 July 2009; accepted 14 July 2009) ABSTRACT The oldest unequivocal records of Dinosauria were unearthed from Late Triassic rocks (approximately 230 Ma) accumulated over extensional rift basins in southwestern Pangea. The better known of these are Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis, Pisanosaurus mertii, Eoraptor lunensis,andPanphagia protos from the Ischigualasto Formation, Argentina, and Staurikosaurus pricei and Saturnalia tupiniquim from the Santa Maria Formation, Brazil. No uncontroversial dinosaur body fossils are known from older strata, but the Middle Triassic origin of the lineage may be inferred from both the footprint record and its sister-group relation to Ladinian basal dinosauromorphs. These include the typical Marasuchus lilloensis, more basal forms such as Lagerpeton and Dromomeron, as well as silesaurids: a possibly monophyletic group composed of Mid-Late Triassic forms that may represent immediate sister taxa to dinosaurs. The first phylogenetic definition to fit the current understanding of Dinosauria as a node-based taxon solely composed of mutually exclusive Saurischia and Ornithischia was given as ‘‘all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of birds and Triceratops’’. -

Surface Geology Wind/Bighorn River Basin Wyoming and Montana

WYOMING STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Plate I Thomas A. Drean, State Geologist Wind/Bighorn Basin Plan II - Available Groundwater Determination Technical Memorandum Surface Geology - Wind/Bighorn River Basin SWEET GRASS R25E R5E R15E R30E R10E R20E MONTANA Mm PM Jsg T7S KJ !c Pp Jsg KJ water Qt Surface Geology Ti ! Red Lodge PM DO PM PM Ts Ts p^r PM N ^r DO KJ DO !c Wind/Bighorn River Basin Tts Mm water Mm Ti Ti ^r DO Kmt Ti LOCATION MAP p^r ^r ^r Qt WYOMING Wyoming and Montana Kf Qt Ti p^r !c p^r PM 0 100 250 Miles Tts ^r PM DO Ti Jsg MD Ts Ti MzPz Kmv !Pg Qt compiled DO DO Tts Ts Taw DO DO DO water Qt Kc PM ^r Twl Qt Ob O^ by ^r Mm DO !c MD MONTANA Thr Ti Kc Qr Klc p^r Kmv Kc : # Ts ^r : O^ Nikolaus Gribb, Brett Worman, # Ts # water : PM Taw # Kf : PM !cd : Ket Qb Taw Qu Twp Thr # Ki Twl 345 P$Ma : Thr O^ Qa KJg Tfu : Jsg ^r Qu : :: # Kl (! KJk : Qr Qls Tomas Gracias, and Scott Quillinan Qb : Thr Ts Taw # Tfu 37 PM Kft: : # :: T10S Qls # Thr : # ^r Kc (! Kft Kmt # :::::: p^r :: : Qu KJk Kc MD Taw DO Qu # p^r Qg :: Km KJ WYOMING Taw Ti : Kl 2012 Thr : Qb # # # Qg : water DO Qls ::: !c !Pg !cd MDO water water Kc Qa :::::: :: Kmt ::: : Twl 90 : Ti Ts Qu Qa Qg Kmv !Pcg Mm KJk : Qg : 212 : Qu Qg £¤ Kmv KJ ¨¦§ Tts Taw p^r ^r # Kl : Kf Kf 338 Ob !cd Qu Qu Ttp # (! : : : p^r ::: !Pg O^ MD P$Ma Thr : Qa # DO Km Qls 343 ^r Qls Taw : Qb Qg Qls Qa Km Jsg water (! : Qb # !cd ^r Kc BighornLake : MD # Taw Qa Qls Qt MD A′ MD MD Qg Twl !Pg Qu Qb Tii # Twp ^r water MzPz Qg Tfu Kl ::: Taw Taw Twp Qls : Qt Kmv Qa Ob P$Ma : Thr Qa # Tcr ^r water Qa Kft # Qt O^ -

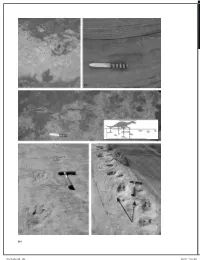

A New Sauropodomorph Ichnogenus from the Lower Jurassic of Sichuan, China Fills a Gap in the Track Record

Historical Biology An International Journal of Paleobiology ISSN: 0891-2963 (Print) 1029-2381 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ghbi20 A new sauropodomorph ichnogenus from the Lower Jurassic of Sichuan, China fills a gap in the track record Lida Xing, Martin G. Lockley, Jianping Zhang, Hendrik Klein, Daqing Li, Tetsuto Miyashita, Zhongdong Li & Susanna B. Kümmell To cite this article: Lida Xing, Martin G. Lockley, Jianping Zhang, Hendrik Klein, Daqing Li, Tetsuto Miyashita, Zhongdong Li & Susanna B. Kümmell (2016) A new sauropodomorph ichnogenus from the Lower Jurassic of Sichuan, China fills a gap in the track record, Historical Biology, 28:7, 881-895, DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2015.1052427 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2015.1052427 Published online: 24 Jun 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 95 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ghbi20 Download by: [University of Alberta] Date: 23 October 2016, At: 09:07 Historical Biology, 2016 Vol. 28, No. 7, 881–895, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2015.1052427 A new sauropodomorph ichnogenus from the Lower Jurassic of Sichuan, China fills a gap in the track record Lida Xinga*, Martin G. Lockleyb, Jianping Zhanga, Hendrik Kleinc, Daqing Lid, Tetsuto Miyashitae, Zhongdong Lif and Susanna B. Ku¨mmellg aSchool of the Earth Sciences and Resources, China University -

Dinotracks.Indb 358 1/22/16 11:23 AM Dinosaur Tracks in Eolian Strata: New Insights Into Track Formation, Walking Kinetics and Trackmaker Behavior 18

358 DinoTracks.indb 358 1/22/16 11:23 AM Dinosaur Tracks in Eolian Strata: New Insights into Track Formation, Walking Kinetics and Trackmaker Behavior 18 David B. Loope and Jesper Milàn Dinosaur tracks are abundant in wind-blown hooves of the bison deformed soft, laminated sediment – the Mesozoic deposits, but the nature of loose eolian sand perfect medium to preserve recognizable tracks. The next makes it difficult to determine how they are preserved. This windstorm buried the tracks. Today, the thick cover of grasses also raises the questions: Why would dinosaurs be walking protects the land surface so well that there are no soft, lami- around in dune fields in the first place? And, if they did go nated sediments for cattle to step on. And, if any tracks were, there, why would their tracks not be erased by the next wind somehow, to get formed, no moving sediment would be avail- storm? able to bury them. Mesozoic eolian sediments around the world, which have been the focus of a number of case studies Introduction in recent years, preserve the tracks of dinosaurs that walked on actively migrating sand dunes. This chapter summarizes Most dunes today form only in deserts and along shore- the known occurrences of dinosaur tracks in Mesozoic eo- lines – the only sandy land surfaces that are nearly devoid of lian strata and discusses their unique modes of preservation plants. Normally plants slow the wind at the ground surface and the anatomical and behavioral information about the enough that sand will not move even when the plant cover trackmakers that can be deduced from them. -

The Anatomy and Phylogenetic Relationships of Antetonitrus Ingenipes (Sauropodiformes, Dinosauria): Implications for the Origins of Sauropoda

THE ANATOMY AND PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF ANTETONITRUS INGENIPES (SAUROPODIFORMES, DINOSAURIA): IMPLICATIONS FOR THE ORIGINS OF SAUROPODA Blair McPhee A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of the Witwatersrand, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. Johannesburg, 2013 i ii ABSTRACT A thorough description and cladistic analysis of the Antetonitrus ingenipes type material sheds further light on the stepwise acquisition of sauropodan traits just prior to the Triassic/Jurassic boundary. Although the forelimb of Antetonitrus and other closely related sauropododomorph taxa retains the plesiomorphic morphology typical of a mobile grasping structure, the changes in the weight-bearing dynamics of both the musculature and the architecture of the hindlimb document the progressive shift towards a sauropodan form of graviportal locomotion. Nonetheless, the presence of hypertrophied muscle attachment sites in Antetonitrus suggests the retention of an intermediary form of facultative bipedality. The term Sauropodiformes is adopted here and given a novel definition intended to capture those transitional sauropodomorph taxa occupying a contiguous position on the pectinate line towards Sauropoda. The early record of sauropod diversification and evolution is re- examined in light of the paraphyletic consensus that has emerged regarding the ‘Prosauropoda’ in recent years. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to express sincere gratitude to Adam Yates for providing me with the opportunity to do ‘real’ palaeontology, and also for gladly sharing his considerable knowledge on sauropodomorph osteology and phylogenetics. This project would not have been possible without the continued (and continual) support (both emotionally and financially) of my parents, Alf and Glenda McPhee – Thank you. -

And Early Jurassic Sediments, and Patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic

and Early Jurassic sediments, and patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic PAUL E. OLSEN AND tetrapod transition HANS-DIETER SUES Introduction parent answer was that the supposed mass extinc- The Late Triassic-Early Jurassic boundary is fre- tions in the tetrapod record were largely an artifact quently cited as one of the thirteen or so episodes of incorrect or questionable biostratigraphic corre- of major extinctions that punctuate Phanerozoic his- lations. On reexamining the problem, we have come tory (Colbert 1958; Newell 1967; Hallam 1981; Raup to realize that the kinds of patterns revealed by look- and Sepkoski 1982, 1984). These times of apparent ing at the change in taxonomic composition through decimation stand out as one class of the great events time also profoundly depend on the taxonomic levels in the history of life. and the sampling intervals examined. We address Renewed interest in the pattern of mass ex- those problems in this chapter. We have now found tinctions through time has stimulated novel and com- that there does indeed appear to be some sort of prehensive attempts to relate these patterns to other extinction event, but it cannot be examined at the terrestrial and extraterrestrial phenomena (see usual coarse levels of resolution. It requires new fine- Chapter 24). The Triassic-Jurassic boundary takes scaled documentation of specific faunal and floral on special significance in this light. First, the faunal transitions. transitions have been cited as even greater in mag- Stratigraphic correlation of geographically dis- nitude than those of the Cretaceous or the Permian junct rocks and assemblages predetermines our per- (Colbert 1958; Hallam 1981; see also Chapter 24). -

Appendix 1 – Environmental Predictor Data

APPENDIX 1 – ENVIRONMENTAL PREDICTOR DATA CONTENTS Overview ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Climate ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Hydrology ................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Land Use and Land Cover ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Soils and Substrate .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Topography .............................................................................................................................................................................. 10 References ................................................................................................................................................................................ 12 1 OVERVIEW A set of 94 potential predictor layers compiled to use in distribution modeling for the target taxa. Many of these layers derive from previous modeling work by WYNDD1, 2, but a -

) Baieiicanjizseum

)SovitatesbAieiicanJizseum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 1901 JULY 22, 1958 Coelurosaur Bone Casts from the Con- necticut Valley Triassic BY EDWIN HARRIS COLBERT1 AND DONALD BAIRD2 INTRODUCTION An additional record of a coelurosaurian dinosaur in the uppermost Triassic of the Connecticut River Valley is provided by a block of sandstone bearing the natural casts of a pubis, tibia, and ribs. This specimen, collected nearly a century ago but hitherto unstudied, was brought to light by the junior author among the collections (at present in dead storage) of the Boston Society of Natural History. We are much indebted to Mr. Bradford Washburn and Mr. Chan W. Wald- ron, Jr., of the Boston Museum of Science for their assistance in mak- ing this material available for study. The source and history of this block of stone are revealed in brief notices published at the time of its discovery. The Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History (vol. 10, p. 42) record that on June 1, 1864, Prof. William B. Rogers "presented an original cast in sand- stone of bones from the Mesozoic rocks of Middlebury, Ct. The stone was probably the same as that used in the construction of the Society's Museum; it was found at Newport among the stones used in the erec- tion of Fort Adams, and he owed his possession of it to the kindness of Capt. Cullum." S. H. Scudder, custodian of the museum, listed the 1 Curator of Fossil Reptiles and Amphibians, the American Museum of Natural History. -

Sequence Stratigraphic Expression of Flexural Subsidence: Middle

SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHIC EXPRESSION OF FLEXURAL SUBSIDENCE: MIDDLE JURASSIC TWIN CREEK LIMESTONE, WYOMING, U.S.A. by BOLTON HOWES (Under the Direction of Steve Holland) ABSTRACT In southwestern Wyoming, the Bajocian to Callovian Twin Creek Limestone records the incipient deposition on a foreland basin in the Sundance Seaway. The sequence stratigraphy of the Twin Creek Limestone is described in the Wyoming Range of southwestern Wyoming, and the geometry of the foreland basin is described mathematically based on estimates flexural rigidity of the underlying crust and the subsidence caused by a thrust load in central Idaho. Four depositional sequences are described. These sequences are correlated to the Bighorn Basin based on existing biostratigraphic correlations and descriptions of the sequence stratigraphic architecture of Middle Jurassic strata in the Bighorn Basin. Modeling of the flexural subsidence of the foreland basin indicates that to account for the geometry of the foreland basin some form of long-wavelength subsidence must be superimposed on the flexural subsidence associated with the thrust load in central Idaho. INDEX WORDS: carbonate rocks; Jurassic; foreland basin; sequence stratigraphy SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHIC EXPRESSION OF FLEXURAL SUBSIDENCE: MIDDLE JURASSIC TWIN CREEK LIMESTONE, WYOMING, U.S.A. By BOLTON HOWES B.A., Macalester College, 2015 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2017 © 2017 Bolton Howes All Rights Reserved SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHIC EXPRESSION OF FLEXURAL SUBSIDENCE: MIDDLE JURASSIC TWIN CREEK LIMESTONE, WYOMING, U.S.A. by BOLTON HOWES Major Professor: Steven M. Holland Committee: L. Bruce Railsback David S. -

Earliest Jurassic U-Pb Ages from Carbonate Deposits in the Navajo Sandstone, Southeastern Utah, USA Judith Totman Parrish1*, E

https://doi.org/10.1130/G46338.1 Manuscript received 3 April 2019 Revised manuscript received 10 July 2019 Manuscript accepted 11 August 2019 © 2019 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Published online 4 September 2019 Earliest Jurassic U-Pb ages from carbonate deposits in the Navajo Sandstone, southeastern Utah, USA Judith Totman Parrish1*, E. Troy Rasbury2, Marjorie A. Chan3 and Stephen T. Hasiotis4 1 Department of Geological Sciences, University of Idaho, P.O. Box 443022, Moscow, Idaho 83844, USA 2 Department of Geosciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York 11794, USA 3 Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah, 115 S 1460 E, Room 383, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112-0102, USA 4 Department of Geology, University of Kansas, 115 Lindley Hall, 1475 Jayhawk Boulevard, Lawrence, Kansas 66045-7594, USA ABSTRACT with the lower part of the Navajo Sandstone New uranium-lead (U-Pb) analyses of carbonate deposits in the Navajo Sandstone in across a broad region from southwestern Utah southeastern Utah (USA) yielded dates of 200.5 ± 1.5 Ma (earliest Jurassic, Hettangian Age) to northeastern Arizona (Blakey, 1989; Hassan and 195.0 ± 7.7 Ma (Early Jurassic, Sinemurian Age). These radioisotopic ages—the first re- et al., 2018). The Glen Canyon Group is under- ported from the Navajo erg and the oldest ages reported for this formation—are critical for lain by the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation, understanding Colorado Plateau stratigraphy because they demonstrate that initial Navajo which includes the Black Ledge sandstone (e.g., Sandstone deposition began just after the Triassic and that the base of the unit is strongly Blakey, 2008; Fig.