FX Swaps and Forwards: Missing Global Debt?1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 1256 and Foreign Currency Derivatives

Section 1256 and Foreign Currency Derivatives Viva Hammer1 Mark-to-market taxation was considered “a fundamental departure from the concept of income realization in the U.S. tax law”2 when it was introduced in 1981. Congress was only game to propose the concept because of rampant “straddle” shelters that were undermining the U.S. tax system and commodities derivatives markets. Early in tax history, the Supreme Court articulated the realization principle as a Constitutional limitation on Congress’ taxing power. But in 1981, lawmakers makers felt confident imposing mark-to-market on exchange traded futures contracts because of the exchanges’ system of variation margin. However, when in 1982 non-exchange foreign currency traders asked to come within the ambit of mark-to-market taxation, Congress acceded to their demands even though this market had no equivalent to variation margin. This opportunistic rather than policy-driven history has spawned a great debate amongst tax practitioners as to the scope of the mark-to-market rule governing foreign currency contracts. Several recent cases have added fuel to the debate. The Straddle Shelters of the 1970s Straddle shelters were developed to exploit several structural flaws in the U.S. tax system: (1) the vast gulf between ordinary income tax rate (maximum 70%) and long term capital gain rate (28%), (2) the arbitrary distinction between capital gain and ordinary income, making it relatively easy to convert one to the other, and (3) the non- economic tax treatment of derivative contracts. Straddle shelters were so pervasive that in 1978 it was estimated that more than 75% of the open interest in silver futures were entered into to accommodate tax straddles and demand for U.S. -

Interest Rate Options

Interest Rate Options Saurav Sen April 2001 Contents 1. Caps and Floors 2 1.1. Defintions . 2 1.2. Plain Vanilla Caps . 2 1.2.1. Caplets . 3 1.2.2. Caps . 4 1.2.3. Bootstrapping the Forward Volatility Curve . 4 1.2.4. Caplet as a Put Option on a Zero-Coupon Bond . 5 1.2.5. Hedging Caps . 6 1.3. Floors . 7 1.3.1. Pricing and Hedging . 7 1.3.2. Put-Call Parity . 7 1.3.3. At-the-money (ATM) Caps and Floors . 7 1.4. Digital Caps . 8 1.4.1. Pricing . 8 1.4.2. Hedging . 8 1.5. Other Exotic Caps and Floors . 9 1.5.1. Knock-In Caps . 9 1.5.2. LIBOR Reset Caps . 9 1.5.3. Auto Caps . 9 1.5.4. Chooser Caps . 9 1.5.5. CMS Caps and Floors . 9 2. Swap Options 10 2.1. Swaps: A Brief Review of Essentials . 10 2.2. Swaptions . 11 2.2.1. Definitions . 11 2.2.2. Payoff Structure . 11 2.2.3. Pricing . 12 2.2.4. Put-Call Parity and Moneyness for Swaptions . 13 2.2.5. Hedging . 13 2.3. Constant Maturity Swaps . 13 2.3.1. Definition . 13 2.3.2. Pricing . 14 1 2.3.3. Approximate CMS Convexity Correction . 14 2.3.4. Pricing (continued) . 15 2.3.5. CMS Summary . 15 2.4. Other Swap Options . 16 2.4.1. LIBOR in Arrears Swaps . 16 2.4.2. Bermudan Swaptions . 16 2.4.3. Hybrid Structures . 17 Appendix: The Black Model 17 A.1. -

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: Analysing the Super-Senior Swap Element

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: analysing the Super-Senior Swap element Nicoletta Baldini * July 2003 Basic Facts In a typical cash flow securitization a SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) transfers interest income and principal repayments from a portfolio of risky assets, the so called asset pool, to a prioritized set of tranches. The level of credit exposure of every single tranche depends upon its level of subordination: so, the junior tranche will be the first to bear the effect of a credit deterioration of the asset pool, and senior tranches the last. The asset pool can be made up by either any type of debt instrument, mainly bonds or bank loans, or Credit Default Swaps (CDS) in which the SPV sells protection1. When the asset pool is made up solely of CDS contracts we talk of ‘synthetic’ Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs); in the so called ‘semi-synthetic’ CDOs, instead, the asset pool is made up by both debt instruments and CDS contracts. The tranches backed by the asset pool can be funded or not, depending upon the fact that the final investor purchases a true debt instrument (note) or a mere synthetic credit exposure. Generally, when the asset pool is constituted by debt instruments, the SPV issues notes (usually divided in more tranches) which are sold to the final investor; in synthetic CDOs, instead, tranches are represented by basket CDSs with which the final investor sells protection to the SPV. In any case all the tranches can be interpreted as percentile basket credit derivatives and their degree of subordination determines the percentiles of the asset pool loss distribution concerning them It is not unusual to find both funded and unfunded tranches within the same securitisation: this is the case for synthetic CDOs (but the same could occur with semi-synthetic CDOs) in which notes are issued and the raised cash is invested in risk free bonds that serve as collateral. -

Ice Crude Oil

ICE CRUDE OIL Intercontinental Exchange® (ICE®) became a center for global petroleum risk management and trading with its acquisition of the International Petroleum Exchange® (IPE®) in June 2001, which is today known as ICE Futures Europe®. IPE was established in 1980 in response to the immense volatility that resulted from the oil price shocks of the 1970s. As IPE’s short-term physical markets evolved and the need to hedge emerged, the exchange offered its first contract, Gas Oil futures. In June 1988, the exchange successfully launched the Brent Crude futures contract. Today, ICE’s FSA-regulated energy futures exchange conducts nearly half the world’s trade in crude oil futures. Along with the benchmark Brent crude oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil and gasoil futures contracts, ICE Futures Europe also offers a full range of futures and options contracts on emissions, U.K. natural gas, U.K power and coal. THE BRENT CRUDE MARKET Brent has served as a leading global benchmark for Atlantic Oseberg-Ekofisk family of North Sea crude oils, each of which Basin crude oils in general, and low-sulfur (“sweet”) crude has a separate delivery point. Many of the crude oils traded oils in particular, since the commercialization of the U.K. and as a basis to Brent actually are traded as a basis to Dated Norwegian sectors of the North Sea in the 1970s. These crude Brent, a cargo loading within the next 10-21 days (23 days on oils include most grades produced from Nigeria and Angola, a Friday). In a circular turn, the active cash swap market for as well as U.S. -

Tax Treatment of Derivatives

United States Viva Hammer* Tax Treatment of Derivatives 1. Introduction instruments, as well as principles of general applicability. Often, the nature of the derivative instrument will dictate The US federal income taxation of derivative instruments whether it is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset is determined under numerous tax rules set forth in the US (see discussion of section 1256 contracts, below). In other tax code, the regulations thereunder (and supplemented instances, the nature of the taxpayer will dictate whether it by various forms of published and unpublished guidance is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset (see discus- from the US tax authorities and by the case law).1 These tax sion of dealers versus traders, below). rules dictate the US federal income taxation of derivative instruments without regard to applicable accounting rules. Generally, the starting point will be to determine whether the instrument is a “capital asset” or an “ordinary asset” The tax rules applicable to derivative instruments have in the hands of the taxpayer. Section 1221 defines “capital developed over time in piecemeal fashion. There are no assets” by exclusion – unless an asset falls within one of general principles governing the taxation of derivatives eight enumerated exceptions, it is viewed as a capital asset. in the United States. Every transaction must be examined Exceptions to capital asset treatment relevant to taxpayers in light of these piecemeal rules. Key considerations for transacting in derivative instruments include the excep- issuers and holders of derivative instruments under US tions for (1) hedging transactions3 and (2) “commodities tax principles will include the character of income, gain, derivative financial instruments” held by a “commodities loss and deduction related to the instrument (ordinary derivatives dealer”.4 vs. -

An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming John Jackson Ada Li Asani Sarkar Patricia Zobel Staff Report No. 557 March 2012 Revised October 2012 FRBNY Staff REPORTS This paper presents preliminary fi ndings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily refl ective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming, John Jackson, Ada Li, Asani Sarkar, and Patricia Zobel Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 557 March 2012; revised October 2012 JEL classifi cation: G12, G13, G18 Abstract This paper examines the over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives (IRD) market in order to inform the design of post-trade price reporting. Our analysis uses a novel transaction-level data set to examine trading activity, the composition of market participants, levels of product standardization, and market-making behavior. We fi nd that trading activity in the IRD market is dispersed across a broad array of product types, currency denominations, and maturities, leading to more than 10,500 observed unique product combinations. While a select group of standard instruments trade with relative frequency and may provide timely and pertinent price information for market partici- pants, many other IRD instruments trade infrequently and with diverse contract terms, limiting the impact on price formation from the reporting of those transactions. -

The Feasibility of Farm Revenue Insurance in Australia

THE FEASIBILITY OF FARM REVENUE INSURANCE IN AUSTRALIA Miranda P.M. Meuwissen1, Ruud B.M. Huirne1, J. Brian Hardaker1/2 1 Department of Economics and Management, Wageningen Agricultural University, The Netherlands 2 Graduate School of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of New England, Australia ABSTRACT Arrow (1965) stated that making markets for trading risk more complete can be socially beneficial. Within this perspective, we discuss the feasibility of farm revenue insurance for Australian agriculture. The feasibility is first discussed from an insurer's point of view. Well-known problems of moral hazard, adverse selection and systemic risk are central. Then, the feasibility is studied from a farmer’s point of view. A simulation model illustrates that gross revenue insurance can be both cheaper and more effective than separate price and yield insurance schemes. We argue that due to the systemic nature of price and yields risks within years and the positive correlation between years, some public- private partnership for reinsurance may be necessary for insurers to enter the gross revenue insurance market. Pros and cons of alternative forms of a public-private partnership are discussed. Once insurers can deal with the systemic risk problem, we conclude that there are opportunities for crop gross revenue insurance schemes, especially if based on area yields and on observed spot market prices. For insurance schemes to cover individual farmer’s yields and prices, we regard the concept of coinsurance as crucial. With respect to livestock commodities, we argue that yields are difficult to include in an insurance scheme and we propose aspects of further research in the field of price and rainfall insurance. -

The Federal Government's Use of Interest Rate Swaps and Currency

The Federal Government’s Use of Interest Rate Swaps and Currency Swaps John Kiff, Uri Ron, and Shafiq Ebrahim, Financial Markets Department • Interest rate swaps and currency swaps are swap agreement is a contract in which contracts in which counterparties agree to two counterparties arrange to exchange exchange cash flows according to a pre-arranged cash-flow streams over a period of time A according to a pre-arranged formula. Two formula. In its capacity as fiscal agent for the federal government, the Bank of Canada has of the most common swap agreements are interest rate carried out swap agreements since fiscal year swaps and currency swaps. In an interest rate swap, counterparties exchange a series of interest payments 1984/85. denominated in the same currency; in a currency • The government uses these swap agreements to swap, counterparties exchange a series of interest pay- obtain cost-effective financing, to fund its foreign ments denominated in different currencies. There is exchange reserves, and to permit flexibility in no exchange of principal in an interest rate swap, but a managing its liabilities. principal payment is exchanged at the beginning and • To minimize its exposure to counterparty credit upon maturity of a currency-swap agreement. risk, the government applies strict credit-rating The swaps market originated in the late 1970s, when criteria and conservative exposure limits based on simultaneous loans were arranged between British a methodology developed by the Bank for and U.S. entities to bypass regulatory barriers on the International Settlements. movement of foreign currency. The first-known foreign currency swap transaction was between the World • Between fiscal 1987/88 and 1994/95, the Bank and IBM in August 1981 and was arranged by government used domestic interest rate swaps to Salomon Brothers (Das 1994, 14–36). -

European Tracker of Financing Measures

20 May 2020 This publication provides a high level summary of the targeted measures taken in the United Kingdom and selected European jurisdictions, designed to support businesses and provide relief from the impact of COVID-19. This information has been put together with the assistance of Wolf Theiss for Austria, Stibbe for Benelux, Kromann Reumert for Denmark, Arthur Cox for Ireland, Gide Loyrette Nouel for France, Noerr for Germany, Gianni Origoni, Grippo, Capelli & Partners for Italy, BAHR for Norway, Cuatrecasas for Portugal and Spain, Roschier for Finland and Sweden, Bär & Karrer AG for Switzerland. We would hereby like to thank them very much for their assistance. Ropes & Gray is maintaining a Coronavirus resource centre at www.ropesgray.com/en/coronavirus which contains information in relation to multiple geographies and practices with our UK related resources here. JURISDICTION PAGE EU LEVEL ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 UNITED KINGDOM ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 IRELAND .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

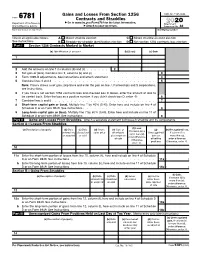

Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to for the Latest Information

Gains and Losses From Section 1256 OMB No. 1545-0644 Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form6781 for the latest information. 2020 Department of the Treasury Attachment Internal Revenue Service ▶ Attach to your tax return. Sequence No. 82 Name(s) shown on tax return Identifying number Check all applicable boxes. A Mixed straddle election C Mixed straddle account election See instructions. B Straddle-by-straddle identification election D Net section 1256 contracts loss election Part I Section 1256 Contracts Marked to Market (a) Identification of account (b) (Loss) (c) Gain 1 2 Add the amounts on line 1 in columns (b) and (c) . 2 ( ) 3 Net gain or (loss). Combine line 2, columns (b) and (c) . 3 4 Form 1099-B adjustments. See instructions and attach statement . 4 5 Combine lines 3 and 4 . 5 Note: If line 5 shows a net gain, skip line 6 and enter the gain on line 7. Partnerships and S corporations, see instructions. 6 If you have a net section 1256 contracts loss and checked box D above, enter the amount of loss to be carried back. Enter the loss as a positive number. If you didn’t check box D, enter -0- . 6 7 Combine lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Short-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 40% (0.40). Enter here and include on line 4 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. See instructions . 8 9 Long-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 60% (0.60). Enter here and include on line 11 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. -

Securitization of Insurance Liabilities

RECORD OF SOCIETY OF ACTUARIES 1995 VOL. 21 NO. 2 SECURITIZATION OF INSURANCE LIABILITIES Instructors: HANS B!2HLMANN* SAMUEL H. COX Recorder: SAMUEL H. COX Securitization of insurance liabilities allows capital to enter insurance markets more efficiently by establishing insurance-based securities. The mortgage market has been securitized, and it may be possible to make a similar market for insurance liabilities. This should be of interest to actuaries working in reinsurance (the Chicago Board of Trade options are in direct competition with property and casualty reinsurers), investments, or financial management. MR. SAMUEL H. COX: I'm from Georgia State University. This session is on securifiza- tion of insurance risk. Hans Biihlmann is the main instructor for this teaching session. Hans will give a presentation on some ideas about securifization of insurance risk. In the second period I'll give some specific examples from the Chicago Board of Trade's insur- ance futures and options. A third period will allow for discussion. Hans is visiting us from the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, where he is a professor of mathematics. He is also former president of the Institute and former dean of faculty. He serves on the board of Swiss Re and is involved in a number of other activities in the actuarial profession in Europe. With that brief introduction, I'll turn it over to Professor Bfihlmarm. MR. HANS BIJHLMANN: A symposium will beheld next week at Georgia State University. It is about alternative risk transfers, alternative in the sense that, until now, risk transfers in insurance have typically been done through the channel of reinsurance. -

DEPARTMENT of the TREASURY Determination of Foreign Exchange

This document has been submitted to the Office of the Federal Register (OFR) for publication and is pending placement on public display at the OFR and publication in the Federal Register. The document may vary slightly from the published document if minor editorial changes have been made during the OFR review process. Upon publication in the Federal Register, the regulation can be found at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/fr/, www.regulations.gov, and at www.treasury.gov. The document published in the Federal Register is the official document. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Determination of Foreign Exchange Swaps and Foreign Exchange Forwards under the Commodity Exchange Act AGENCY: Department of the Treasury, Departmental Offices. ACTION: Notice of Proposed Determination. SUMMARY: The Commodity Exchange Act (―CEA‖), as amended by Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (―Dodd-Frank Act‖), authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury (―Secretary‖) to issue a written determination exempting foreign exchange swaps, foreign exchange forwards, or both, from the definition of a ―swap‖ under the CEA. The Secretary proposes to issue a determination that would exempt both foreign exchange swaps and foreign exchange forwards from the definition of ―swap,‖ in accordance with the relevant provisions of the CEA and invites comment on the proposed determination, as well as the factors supporting such a determination. DATES: Written comments must be received on or before [INSERT DATE THAT IS 30 DAYS AFTER PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER], to be assured of consideration. ADDRESSES: Submission of Comments by mail: You may submit comments to: Office of Financial Markets, Department of the Treasury, 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue N.W., Washington, DC, 20220.