Mastering Metering 7 Simple and Powerful Techniques That I Use to Nail My Exposure in Wildlife Photography (And You Can Totally Do It Too!)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Metering on a DSLR

Getting more from your Camera Topic 4 - Introduction to Metering on a DSLR Learning Outcomes In this lesson, we will look at another important feature on a DSLR camera called “Metering Mode”. By the end of this lesson, you will have a better idea of the role that metering plays when thinking about exposure in your photography. Page | 1 Introduction to Metering on a DSLR Introduction to Metering “Metering Mode” may also be called “Camera Metering”, “Exposure Metering” or even “Metering”. One of the things that might have already frustrated you is a scenario in which some photographs come out too bright or, in some cases, too dark. By understanding the metering modes, you will be better equipped to tackle this. Let us first talk about what metering is, before moving on to see how it works and how you can use your understanding of it, to enhance your photography. 1) What is Metering? Metering, in its simplest meaning, is basically how your camera determines what the correct shutter speed and aperture should be, depending on the amount of light that goes into the camera and the sensitivity of the sensor. In the age of digital technology, we are fortunate enough that every DSLR camera is built with an integrated light meter. This device is clever in that it automatically measures the reflected light and determines the optimal exposure. It’s important to look at the most common metering modes that are found in digital cameras today: 1. Matrix Metering (Nikon), also known as Evaluative Metering (Canon) 2. Center-weighted Metering 3. -

EXIF: a Format Is Worth a Thousand Words

NATIONAL LAW ENFORCEMENT AND CORRECTIONS TECHNOLOGY CENTER A program of the Office of Justice Programs’ National Institute of Justice From Winter 2007 TechBeat TECH b • e • a • t Dedicated to Reporting Developments in Technology for Law Enforcement, Corrections, and Forensic Sciences EXIF: A Format Is Worth A Thousand Words he National Center for Missing & Exploited Children if they are used only to open the file. If, however, these T revealed in a June 2005 study that 40 percent of arrest- programs are used to modify an image, they can destroy ed child pornography possessors had both sexually the Exif data. victimized children and were in possession of child pornog- The most important data may be the thumbnail image raphy. Due in part to the increasing prevalence of child exploitation and pornography, the digital photograph has linked to the photograph. Thumbnails are saved in their now become a fixture in gathering and examining forensic own hidden file (a thumbs.db file placed in folders con- evidence in such cases. taining images on the computer), and changes to an image may not always transfer to the corresponding Investigators who frequently handle child pornogra- thumbnail. If an original image is wiped from a disk using phy cases usually have (or know where to access) the a program such as Secure Clean™ or BCWipe®, the thumb- tools and the knowledge to obtain evidence associated nail may still be available. Officers have encountered situ- with contraband images. Nevertheless, law enforcement ations in which the victim’s or perpetrator’s face was officers who do not handle these cases on a regular basis blurred or concealed in the full image, but the thumbnail may be unaware of the important data that can be depicted an older version that revealed the obscured derived from digital images. -

Understanding Metering and Metering Modes

Understanding Metering and Metering Modes Every modern DSLR has something called “Metering Mode”, also known as “Camera Metering”, “Exposure Metering” or simply “Metering”. Knowing how metering works and what each of the metering modes does is important in photography, because it helps photographers control their exposure with minimum effort and take better pictures in unusual lighting situations. In this understanding metering modes article, I will explain what metering is, how it works and how you can use it for your digital photography. What is Metering? Metering is how your camera determines what the correct shutter speed and aperture should be, depending on the amount of light that goes into the camera and the ISO. Back in the old days of photography, cameras were not equipped with a light “meter”, which is a sensor that measures the amount and intensity of light. Photographers had to use hand-held light meters to determine the optimal exposure. Obviously, because the work was shot on film, they could not preview or see the results immediately, which is why they religiously relied on those light meters. Today, every DSLR has an integrated light meter that automatically measures the reflected light and determines the optimal exposure. The most common metering modes in digital cameras today are: 1. Matrix Metering (Nikon), also known as Evaluative Metering (Canon) 2. Center-weighted Metering 3. Spot Metering Some Canon EOS models also offer “Partial Metering”, which is similar to Spot Metering, except the covered area is larger (approximately 8% of the viewfinder area near the center vs 3.5% in Spot Metering). -

Intro to Digital Photography.Pdf

ABSTRACT Learn and master the basic features of your camera to gain better control of your photos. Individualized chapters on each of the cameras basic functions as well as cheat sheets you can download and print for use while shooting. Neuberger, Lawrence INTRO TO DGMA 3303 Digital Photography DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY Mastering the Basics Table of Contents Camera Controls ............................................................................................................................. 7 Camera Controls ......................................................................................................................... 7 Image Sensor .............................................................................................................................. 8 Camera Lens .............................................................................................................................. 8 Camera Modes ............................................................................................................................ 9 Built-in Flash ............................................................................................................................. 11 Viewing System ........................................................................................................................ 11 Image File Formats ....................................................................................................................... 13 File Compression ...................................................................................................................... -

Nikon D5100: from Snapshots to Great Shots

Nikon D5100: From Snapshots to Great Shots Rob Sylvan Nikon D5100: From Snapshots to Great Shots Rob Sylvan Peachpit Press 1249 Eighth Street Berkeley, CA 94710 510/524-2178 510/524-2221 (fax) Find us on the Web at www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education Copyright © 2012 by Peachpit Press Senior Acquisitions Editor: Nikki McDonald Associate Editor: Valerie Witte Production Editor: Lisa Brazieal Copyeditor: Scout Festa Proofreader: Patricia Pane Composition: WolfsonDesign Indexer: Valerie Haynes Perry Cover Image: Rob Sylvan Cover Design: Aren Straiger Back Cover Author Photo: Rob Sylvan Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact permissions@ peachpit.com. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks All Nikon products are trademarks or registered trademarks of Nikon and/or Nikon Corporation. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. -

E-300 Advanced Manual

E-300AdEN-Cover 04.10.22 11:43 AM Page 1 Basic operations DIGITDIGITALAL CAMERA Things to know before shooting http://www.olympus.com/ Selecting the right mode for shooting conditions ADVANCED MANUAL ADVANCED ADADVANCEDVANCED MANUMANUALAL Shinjuku Monolith, 3-1 Nishi-Shinjuku 2-chome, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan Various shooting functions Focusing functions Two Corporate Center Drive, PO Box 9058, Melville, NY 11747-9058, U.S.A. Tel. 1-631-844-5000 Exposure, image and color Technical Support (USA) 24/7 online automated help: http://www.olympusamerica.com/E1 Phone customer support: Tel. 1-800-260-1625 (Toll-free) Playback Our phone customer support is available from 8 am to 10 pm (Monday to Friday) ET Customizing the settings/ E-Mail: [email protected] functions of your camera Olympus software updates can be obtained at: http://www.olympus.com/digital Printing Premises: Wendenstrasse 14-18, 20097 Hamburg, Germany Transferring images to a Tel. +49 40 - 23 77 3-0 / Fax +49 40 - 23 07 61 computer Goods delivery: Bredowstrasse 20, 22113 Hamburg, Germany Letters: Postfach 10 49 08, 20034 Hamburg, Germany Appendix European Technical Customer Support: Please visit our homepage http://www.olympus-europa.com or call our TOLL FREE NUMBER*: 00800 - 67 10 83 00 Information for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom * Please note some (mobile) phone services/provider do not permit access or request an additional prefix to +800 numbers. For all not listed European Countries and in case that you can’t get connected to ● Thank you for purchasing an Olympus digital camera. -

A Simple Guide to Help You Learn Your Camera So You Can Enjoy Your Time Outdoors

Low Light Wildlife & Nature Photography A simple guide to help you learn your camera so you can enjoy your time outdoors T RENT SIZEMORE PHOTOGRAPHY Introduction ABOVE: ISO 500 - ƒ/5.0 - 1/200s In order to understand how to Dark clouds, shadows, and dim lights all make for difficult exposures that expose correctly in low light can push the limits of your camera and lens. There is always a situations, you’ll need to compromise between enough light to freeze the action through shutter understand the three aspects of exposure and how far you can push speed and keeping an ISO with an acceptable level of noise and grain. each one to your camera’s limits. By grasping the concepts of exposure in low lighting or difficult lighting situations, you’ll be able to cameras are great at exposing but gives more preference to what’s get the “correct” exposure for any correctly for most scenes you’ll in the center of the scene. If you scene you may encounter. I say encounter, but when you can have something really bright on the “correct” because nothing is set in manually expose using each of the edges of the scene, center-weighted stone. There may be a technically camera settings, you’ll be able to can be helpful for a better exposure. correct exposure for a given scene, fine-tune the exposure to take but you can creatively expose to get advantage of the different attributes Spot metering only measures a the image you want. When you of the light you see. -

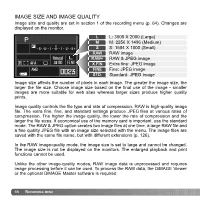

IMAGE SIZE and IMAGE QUALITY Image Size and Quality Are Set in Section 1 of the Recording Menu (P

IMAGE SIZE AND IMAGE QUALITY Image size and quality are set in section 1 of the recording menu (p. 64). Changes are displayed on the monitor. L L: 3008 X 2000 (Large) M M: 2256 X 1496 (Medium) S S: 1504 X 1000 (Small) RAW RAW image RAW+ RAW & JPEG image X.FIN Extra fine: JPEG image FINE Fine: JPEG image STD. Standard: JPEG image Image size affects the number of pixels in each image. The greater the image size, the larger the file size. Choose image size based on the final use of the image - smaller images are more suitable for web sites whereas larger sizes produce higher quality prints. Image quality controls the file type and rate of compression. RAW is high-quality image file. The extra fine, fine, and standard settings produce JPEG files at various rates of compression. The higher the image quality, the lower the rate of compression and the larger the file sizes. If economical use of the memory card is important, use the standard mode. The RAW & JPEG option creates two image files at one time, a large RAW file and a fine quality JPEG file with an image size selected with the menu. The image files are saved with the same file name, but with different extensions (p. 126). In the RAW image-quality mode, the image size is set to large and cannot be changed. The image size is not be displayed on the monitors. The enlarged playback and print functions cannot be used. Unlike the other image-quality modes, RAW image data is unprocessed and requires image processing before it can be used. -

(DSLR) Cameras

Optimizing Radiometric Fidelity to Enhance Aerial Image Change Detection Utilizing Digital Single Lens Reflex (DSLR) Cameras Andrew D. Kerr and Douglas A. Stow Abstract Our objectives are to analyze the radiometric characteris- benefits of replicating solar ephemeris (Coulter et al., 2012, tics and best practices for maximizing radiometric fidel- Ahrends et al., 2008), specific shutter and aperture settings ity of digital single lens reflex (DSLR) cameras for aerial (Ahrends et al., 2008, Lebourgeois et al., 2008), using RAW image-based change detection. Control settings, exposure files (Deanet al., 2000, Coulter et al., 2012, Ahrends et al., values, white balance, light metering, ISO, and lens aper- 2008, Lebourgeois et al., 2008), vignetting abatement (Dean ture are evaluated for several bi-temporal imagery datasets. et al., 2000), and maintaining intra-frame white balance (WB) These variables are compared for their effects on dynamic consistency (Richardson et al., 2009, Levin et al., 2005). range, intra-frame brightness variation, acuity, temporal Through this study we seek to identify and determine how consistency, and detectability of simulated cracks. Test- to compensate and account for, the photometric aspects of im- ing was conducted from a terrestrial, rather than airborne age capture and postprocessing with DSLR cameras, to achieve platform, due to the large number of images collected, and high radiometric fidelity within and between digital multi- to minimize inter-image misregistration. Results point to temporal images. The overall goal is to minimize the effects of exposure biases in the range of −0.7 or −0.3EV (i.e., slightly these factors on the radiometric consistency of multi-temporal less than the auto-exposure selected levels) being preferable images, inter-frame brightness, and capture of images with for change detection and noise minimization, by achiev- high acuity and dynamic range. -

Operating Instructions Q Operating Instructions

EXPOSURE METER Operating Instructions q Operating instructions SAFETY PRECAUTIONS This manual uses the following safety labels for AWARNING and ACAUTION that you must follow. /b WARNING Indicates hazards or unsafe practices that can result in severe personal injurry or death. ACAUTION Indicates hazards or unsafe practices that can rresult in personal injury or damage to your L-308Bll exposure meter. (CAUTIONI Indicates an operation note or limitation you must use. Please read the notes to avoi d an incorrect L-308BII operation. NOTE(S) Provides the reference information and related functions that are useful for your L-308Bll operations. /bA WARNING &ZAUTlON CONTENTS SAFETY PRECAUTIONS .......................................................................................... i CONTENTS .................................................................................................................... ii 1. Parts Designations ...................................................................................... 2. Display ................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 LCD panel .................................................................................................................................. 2 3. Mode Selection ................................................................................................ 3 3.1 Switching between incident light metering and reflected light metering ........... 3 3.2 How to fit the Lumidisc ........................................................................................................................ -

(EXIF) File Headers in Digital Evidence Analysis Special Agent Paul Alvarez Air Force Office of Special Investigations, Computer Investigations and Operations

International Journal of Digital Evidence Winter 2004, Volume 2, Issue 3 Using Extended File Information (EXIF) File Headers in Digital Evidence Analysis Special Agent Paul Alvarez Air Force Office of Special Investigations, Computer Investigations and Operations Abstract An obstacle in any Child Pornography (CP) investigation is the investigator’s ability to determine whether the pictures in question have been altered. Because of the court ruling in Ashcroft v. Free Speech, many agents are asked on the stand if they can prove the pictures they recovered were altered in any way. If the picture doesn’t match any known CP hashes, then it can be very difficult to prove they are untouched. One way an investigator may be able determine if a picture is authentic is through extraction of metadata. In the case of digital pictures, they may contain EXIF headers that can help the investigator to verify the authenticity of a picture. Introduction In the Supreme Court case of John D. Ashcroft, United States Attorney General v. The Free Speech Coalition, the court ruled that modified pictures (pictures that were edited, morphed or created to look like child pornography) were protected under the First Amendment of the Constitution [1]. The court felt that because a real child was not harmed the pictures are protected by the freedom of speech. This may create additional hurdles for investigators. With the use of hash databases compiled by law enforcement, it is possible to find previously identified CP on digital media. But how can we verify the remaining pictures? What if the person under investigation was taking pictures of a victim not previously identified by law enforcement? One way to help verify the authenticity of a picture is through the use of metadata. -

INSTRUCTIONS 2 MODE D'emploi 33 BEDIENUNGSANLEITUNG 65 INSTRUCCIONES 97 129 2 WARNING CONTENTS 3 Read This Manual Carefully Before Using Your Camera

INSTRUCTIONS 2 MODE D'EMPLOI 33 BEDIENUNGSANLEITUNG 65 INSTRUCCIONES 97 129 2 WARNING CONTENTS 3 Read this manual carefully before using your camera. Indicates circumstances under which Names of parts 2. Exposure mode button ..............16 mishandling resulting from ignoring this symbol could result in personal injury or property Camera Body................................4 [ A ] Aperture Preferred Auto ....17 damage. Camera Body/LCD Panel ..............5 [ S ] Shutter Speed Preferred Auto Viewfinder Display........................6 ..................................................18 KEEP THE BATTERIES AWAY FROM FIRE. NEVER TRY TO DISASSEMBLE, RECHARGE, OR SHORT-CIRCUIT BATTERIES. Using the strap ................................6 [ M ] Manual Exposure ..............19 Diopter adjustment ..........................7 Flash photography KEEP THE BATTERIES OUT OF THE REACH OF CHILDREN. IF A CHILD Loading and checking the batteries ..7 in the Manual Exposure mode....20 SWALLOWS A BATTERY, CONTACT A DOCTOR IMMEDIATELY. Loading the film ..............................8 [ ] Exposure Compensation ........22 NEVER ATTEMPT TO DISASSEMBLE THE CAMERA; IT CONTAINS A HIGH- Taking pictures [ ] Spot Metering ..................24 VOLTAGE CIRCUIT. IF THE INTERNAL PARTS OF THE CAMERA ARE Programmed Auto (FULL AUTO)..9 [ ] Selftimer/ EXPOSED DUE TO DROPPING OR DAMAGE, REMOVE THE BATTERIES [] Remote Control(Optional) ....25 IMMEDIATELY TO PREVENT FURTHER USAGE. Focus Lock ................................10 Unloading the film ..........................10 [ ]