June 19, 2020 the Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse Committee On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 1, 2021 the Honorable Shelley Moore Capito 172 Russell Senate

June 1, 2021 The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito The Honorable Mike Crapo 172 Russell Senate Office Building 239 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable John Barrasso The Honorable Cory Booker 307 Dirksen Senate Office Building 717 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 The Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse 530 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Senators Capito, Barrasso, Whitehouse, Crapo, and Booker: We write to express our support for the American Nuclear Infrastructure Act (ANIA) and to encourage you to reintroduce and advance the legislation. The innovative programs established in this bill support currently operating nuclear reactors and the next generation of reactor technologies. ANIA would direct the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to continue to modernize its regulatory review processes. Efficiencies in the environmental review process and reviewing new license applications will help enable nuclear energy to deploy at a rapid enough scale to support decarbonization. In addition, preemptively reviewing U.S. Department of Energy sites for demonstration reactors can help companies partner with the National Labs to test out innovative concepts, including advanced methods of manufacturing and construction. Awarding prizes to first mover companies supports competition, but also recognizes the challenges of being first through the licensing process when using innovative technologies. The targeted credit program to preserve the existing nuclear fleet, the foundation of our nation’s low carbon electricity, allows plants to continue decreasing operating costs without prematurely shutting down. Advanced nuclear, due to its dispatchable and high temperature attributes, can also be used to decarbonize other energy sectors. -

Appointments to the Legislature Under the Rhode Island Separation Of

Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Fri Dec 13 10:20:44 2019 Citations: Bluebook 20th ed. Sheldon Whitehouse, Appointments by the Legislature under the Rhode Island Separation of Powers Doctrine: The Hazards of the Road Less Traveled, 1 Roger Williams U. L. Rev. 1 (1996). ALWD 6th ed. Sheldon Whitehouse, Appointments by the Legislature under the Rhode Island Separation of Powers Doctrine: The Hazards of the Road Less Traveled, 1 Roger Williams U. L. Rev. 1 (1996). APA 6th ed. Whitehouse, S. (1996). Appointments by the Legislature under the Rhode Island Separation of Powers Doctrine: The Hazards of the Road Less Traveled. Roger Williams University Law Review, 1, 1-30. Chicago 7th ed. Sheldon Whitehouse, "Appointments by the Legislature under the Rhode Island Separation of Powers Doctrine: The Hazards of the Road Less Traveled," Roger Williams University Law Review 1 (1996): 1-30 McGill Guide 9th ed. Sheldon Whitehouse, "Appointments by the Legislature under the Rhode Island Separation of Powers Doctrine: The Hazards of the Road Less Traveled" (1996) 1 Roger Williams U L Rev 1. MLA 8th ed. Whitehouse, Sheldon. "Appointments by the Legislature under the Rhode Island Separation of Powers Doctrine: The Hazards of the Road Less Traveled." Roger Williams University Law Review, 1, 1996, p. 1-30. HeinOnline. OSCOLA 4th ed. Sheldon Whitehouse, 'Appointments by the Legislature under the Rhode Island Separation of Powers Doctrine: The Hazards of the Road Less Traveled' (1996) 1 Roger Williams U L Rev 1 Provided by: Roger Williams University School of Law Library -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -

GUIDE to the 117Th CONGRESS

GUIDE TO THE 117th CONGRESS Table of Contents Health Professionals Serving in the 117th Congress ................................................................ 2 Congressional Schedule ......................................................................................................... 3 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) 2021 Federal Holidays ............................................. 4 Senate Balance of Power ....................................................................................................... 5 Senate Leadership ................................................................................................................. 6 Senate Committee Leadership ............................................................................................... 7 Senate Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................. 8 House Balance of Power ...................................................................................................... 11 House Committee Leadership .............................................................................................. 12 House Leadership ................................................................................................................ 13 House Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................ 14 Caucus Leadership and Membership .................................................................................... 18 New Members of the 117th -

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

Congressional Record—Senate S4894

S4894 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE July 14, 2021 good military strategy for China and Cardin Johnson Romney [Rollcall Vote No. 263 Ex.] Carper Kaine Rosen YEAS—90 Russia, but the budget doesn’t support Casey Kelly Rounds that strategy. As a result, I am worried Cassidy King Sanders Baldwin Grassley Peters that deterrence will fail maybe today Collins Klobuchar Schatz Barrasso Hassan Portman or maybe 5 years from now, and when Coons Leahy Schumer Bennet Heinrich Reed Cornyn Luja´ n Shaheen Blumenthal Hickenlooper Risch it does, the cost will be much higher Cortez Masto Manchin Sinema Blunt Hirono Romney than any investment we would make Crapo Markey Smith Booker Hoeven Rosen today. Daines McConnell Stabenow Boozman Hyde-Smith Rounds Duckworth Merkley Tester Braun Inhofe Rubio We have made a sacred compact with Durbin Moran Thune Brown Kaine Sanders our servicemembers. We tell them that Feinstein Murkowski Toomey Burr Kelly Sasse we will take care of them and take care Fischer Murphy Van Hollen Cantwell Kennedy Schatz of their families. We do that very well, Gillibrand Murray Warner Capito King Schumer Grassley Ossoff Warnock Cardin Klobuchar Scott (SC) but we also tell them that we will give Hassan Padilla Warren Carper Leahy Shaheen them the tools to defend the Nation Heinrich Peters Whitehouse Casey Lee Sinema and to come home safely, but we are Hickenlooper Portman Wicker Cassidy Luja´ n Smith Hirono Reed Wyden Collins Lummis Stabenow not holding up that end of the bargain. Hyde-Smith Risch Young Coons Manchin Sullivan With this proposed budget and the Cornyn Markey Tester prospects of further cuts, we are failing NAYS—27 Cortez Masto Marshall Thune to give them the resources they need. -

Meeting Matrix Meeting Committee Time Office / Intro Member / Staff / Office Participants 8:00 AM House Overview: 2247 Rayburn House Office Building

Meeting Matrix Meeting Committee Time Office / Intro Member / Staff / Office Participants 8:00 AM House Overview: 2247 Rayburn House Office Building 8:30 AM Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-UT) 8:30 AM Kirk Jowers doTerra International OPEN TO ALL PARTICIPANTS 8:45 AM Rep. Erik Paulsen (R-MN) 8:45 AM Jim Hyde Balchem Corporation OPEN TO ALL PARTICIPANTS 8:50 AM Rep. Brett Guthrie (R-KY) 8:50 AM Tobe Cohen DSM Nutritional Products OPEN TO ALL PARTICIPANTS 9:00 AM Rep. Andy Harris (R-MD) 9:00 AM Kristen Blanchard Nutramax Laboratories Consumer Care Inc. OPEN TO ALL PARTICIPANTS 9:10 AM Rep. Tony Cárdenas (D-CA) 9:10 AM Michelle Stout Amway/Nutrilite OPEN TO ALL PARTICIPANTS 9:20 AM Rep. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) 9:20 AM Heather Granato Informa OPEN TO ALL PARTICIPANTS 9:30 AM Rep. Rob Bishop (R-UT) 9:30 AM Bryan Kirkland Innophos, Inc OPEN TO ALL PARTICIPANTS 10:00 AM Robert Latta (OH-05) EC 10:00 AM 2448 Rayburn Rachel Schwegman, Senior LA Team 8 Kurt Schrader (OR-05) EC 10:00 AM 2431 Rayburn Stephen Holland, Legislative Counsel Team 9 Ben Ray Lujan (NM-3) EC 10:00 AM 2231 Rayburn Rep. Ben Ray Lujan, Kim Espinoza, LA Team 16 David Schweikert (AZ-06) WM 10:00 AM 2059 Rayburn Cami Lepire, LA Team 14 Jim Renacci (OH-16) WM 10:00 AM 328 Cannon Shane Hand, LC Team 3 Tom Reed (NY-23) WM 10:00 AM 2437 Rayburn Logan Hoover, LA Team 11 Ron Kind (WI-3) WM 10:00 AM 1502 Longworth Rep. -

Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress

Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION AND FORESTRY BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Pat Roberts, Kansas Debbie Stabenow, Michigan Mike Crapo, Idaho Sherrod Brown, Ohio Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont Richard Shelby, Alabama Jack Reed, Rhode Island Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Sherrod Brown, Ohio Bob Corker, Tennessee Bob Menendez, New Jersey John Boozman, Arkansas Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota Pat Toomey, Pennsylvania Jon Tester, Montana John Hoeven, North Dakota Michael Bennet, Colorado Dean Heller, Nevada Mark Warner, Virginia Joni Ernst, Iowa Kirsten Gillibrand, New York Tim Scott, South Carolina Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts Chuck Grassley, Iowa Joe Donnelly, Indiana Ben Sasse, Nebraska Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota John Thune, South Dakota Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota Tom Cotton, Arkansas Joe Donnelly, Indiana Steve Daines, Montana Bob Casey, Pennsylvania Mike Rounds, South Dakota Brian Schatz, Hawaii David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland Luther Strange, Alabama Thom Tillis, North Carolina Catherine Cortez Masto, Nevada APPROPRIATIONS John Kennedy, Louisiana REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC BUDGET Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Mitch McConnell, Patty Murray, Kentucky Washington Mike Enzi, Wyoming Bernie Sanders, Vermont Richard Shelby, Dianne Feinstein, Alabama California Chuck Grassley, Iowa Patty Murray, -

COVER STORY || INSIDE the SENATE the LOST SENATE If Senators Can't Get Along, How Can They Govern?

COVER STORY || INSIDE THE SENATE THE LOST SENATE If senators can't get along, how can they govern? hirty years ago this fall, Ted Kennedy was running for president, Robert Byrd ruled the Senate floor as majority leader and a boyish Max Baucus had already jumped ahead of his freshman class by securing a seat on the powerful Finance Committee. At West Point, Army Capt. Jack Reed resigned his commission to enter THarvard Law School. In Brooklyn, state Assemblyman Chuck Schumer, Flatbush’s version of a young Lyndon Johnson, prepared to run for the House. And in Louisville, Ky., Jefferson County Judge Mitch McConnell waited — consolidating power, speaking around the state, but always with an eye toward the Senate, where he had interned for his hero, Sen. John Sherman Cooper (R-Ky.), during the great civil rights debate of 1964. “That was when I first decided to try,” McConnell says. Change is a great constant in Congress: One generation is forever giving way to the next. But to look back 30 years at the Senate — when this reporter first came to Washington — is to see the last remnant of something now lost from American government. O C I T OLI By David Rogers John shinkle — P 54 POLITICO POLITICO 53 In 1979, a solid quarter of the senators had lived through the civil rights debate that elected senator — after years in the much larger House. so inspired McConnell. And in them, elements of the old Senate “club” still endured. Only a single row of lights was turned on in the ceiling — the Senate was not in Television had yet to intrude, preserving a greater intimacy and drawing senators session — and the Texan stood at the door, taking in the polished wooden desks to the floor to hear one another’s speeches. -

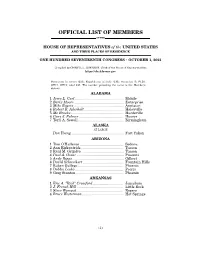

Official List of Members by State

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS • OCTOBER 1, 2021 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives https://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (220); Republicans in italic (212); vacancies (3) FL20, OH11, OH15; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Jerry L. Carl ................................................ Mobile 2 Barry Moore ................................................. Enterprise 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................. Phoenix 8 Debbie Lesko ............................................... -

CRPT-116Srpt19.Pdf

1 116TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 1st Session SENATE 116–19 R E P O R T ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCE OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE DURING THE 115TH CONGRESS PURSUANT TO Rule XXVI of the Standing Rules OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE MARCH 26, 2019.—Ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 89–010 WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 06:51 Mar 28, 2019 Jkt 089010 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 E:\HR\OC\SR019.XXX SR019 seneagle [115TH CONGRESS—COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP] COMMITTEE ON FINANCE ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman CHUCK GRASSLEY, Iowa RON WYDEN, Oregon MIKE CRAPO, Idaho DEBBIE STABENOW, Michigan PAT ROBERTS, Kansas MARIA CANTWELL, Washington MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN CORNYN, Texas ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey JOHN THUNE, South Dakota THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware RICHARD BURR, North Carolina BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia SHERROD BROWN, Ohio ROB PORTMAN, Ohio MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado PATRICK J. TOOMEY, Pennsylvania ROBERT P. CASEY, JR., Pennsylvania DEAN HELLER, Nevada MARK R. WARNER, Virginia TIM SCOTT, South Carolina CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri BILL CASSIDY, Louisiana SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, Rhode Island 1 CHRIS CAMPBELL, Staff Director 2 A. JAY KHOSLA, Staff Director 3 JEFFREY WRASE, Staff Director and Chief Economist 4 JOSHUA SHEINKMAN, Democratic Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEES HEALTH CARE PATRICK J. TOOMEY, Pennsylvania, Chairman CHUCK GRASSLEY, Iowa DEBBIE STABENOW, Michigan PAT ROBERTS, Kansas ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming MARIA CANTWELL, Washington JOHN THUNE, South Dakota THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware RICHARD BURR, North Carolina BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia SHERROD BROWN, Ohio ROB PORTMAN, Ohio MARK R. -

June 7, 2021 Dear Chairs Leahy, Van Hollen, and Shaheen, and Senators

June 7, 2021 Honorable Patrick J. Leahy Honorable Richard C. Shelby Chairman Vice Chairman Committee on Appropriations Committee on Appropriations United States Senate United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Honorable Chris Van Hollen Honorable Cindy Hyde-Smith Chairman Ranking Member Subcommittee on Financial Services Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government and General Government Committee on Appropriations Committee on Appropriations United States Senate United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Honorable Jeanne Shaheen Honorable Jerry Moran Chair Ranking Member Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Science, and Related Agencies Committee on Appropriations Committee on Appropriations United States Senate United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Dear Chairs Leahy, Van Hollen, and Shaheen, and Senators Shelby, Hyde-Smith, and Moran: On May 20, 2021, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 3237, the “Emergency Security Supplemental to Respond to January 6th Appropriations Act, 2021.” As the Senate considers its response to this legislation, we write on behalf of the Judicial Conference of the United States to urge the Senate to include in its bill the $157.5 million in H.R. 3237 for the Judiciary’s Court Security program. This funding is needed for security improvements to “harden” courthouses, for a security vulnerability program to increase judges’ safety, and to reimburse the Federal Protective Service (FPS) for upgrading aging exterior courthouse security cameras. In addition, we strongly Honorable Patrick J. Leahy Honorable Richard C. Shelby Honorable Chris Van Hollen Honorable Cindy Hyde-Smith Honorable Jeanne Shaheen Honorable Jerry Moran Page 2 support the $25.0 million in H.R. -

United States Senate TIM SCOTT, SOUTHCAROLINA ROBERTP

CHUCK GRASSLEY, IOWA, CHAIRMAN MIKE CRAPO IDAHO RON WYDEN OREGON PAT ROBERTS, KANSAS DEBBIESTABENOW, MICHIGAN MICHAELB.ENZIWYOMING MARIACANTWELL, WASHINGTON JOHNCORNYN, TEXAS ROBERTMENENDEZ, NEW JERSEY JOHN THUNE, SOUTHDAKOTA THOMAS R. CARPER DELAWARE RICHARD BURR, NORTH CAROLINA BENJAMIN L.CARDIN, MARYLAND ROB PORTMAN , OHIO SHERRODBROWN, OHIO PATRICKJ. TOOMEY, PENNSYLVANIA MICHAEL BENNET, COLORADO United States Senate TIM SCOTT, SOUTHCAROLINA ROBERTP. CASEY . , PENNSYLVANIA BILL CASSIDY LOUISIANA MARK WARNER VIRGINIA COMMITTEEON FINANCE JAMES LANKFORD OKLAHOMA SHELDON WHITEHOUSE , RHODE ISLAND STEVE DAINES , MONTANA MAGGIEHASSAN, NEWHAMPSHIRE TODDYOUNG, INDIANA CATHERINECORTEZMASTO, NEVADA WASHINGTON, DC 20510-6200 BENSASSE, NEBRASKA KOLANDAVIS, STAFFDIRECTORANDCHIEFCOUNSEL JOSHUASHEINKMAN, DEMOCRATICSTAFFDIRECTOR December02, 2020 The Honorable William Barr Attorney General Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20530 The Honorable ChristopherA. Wray Director Federal Bureau of Investigation 935 PennsylvaniaAvenue, NW Washington, DC 20535 DearAttorney GeneralBarrandDirectorWray: I am writing to you concerning reports of Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) involvement with the Trump Administration's concerning relationship with Turkey's President, Recep Tayyip Erdoan. According to the New York Times, the FBI received requests from the White House to investigate Fethullah Gülen, a permanent U.S. resident and critic of President Erdoan, “ and look for ways to perhaps force him out of the United States. This report is particularly alarming given my ongoing investigation of whether President Trump's personal conflicts of interest drove him to personally interfere in U.S. policy in favor of President Erdoanblames Mr. Gülen for an attempted coup in2016, without producing public evidence for the claim . President Erdoan has also called Mr. Gülen a terrorist and has repeatedly sought his extradition.3 Reportedly, the request to the FBI to remove Mr.