The Cheka's Horrors and on a Raised Beach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Revolutionary Tribunals and the Origins of Terror in Early Soviet Russia

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Revolutionary Tribunals and the Origins of Terror in Early Soviet Russia AUTHORS Rendle, Matthew JOURNAL Historical Research DEPOSITED IN ORE 14 May 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/9361 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 Revolutionary tribunals and the origins of terror in early Soviet Russia* Matthew Rendle University of Exeter Abstract After the October Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks restructured Russia’s legal system, assigning the central role in targeting their enemies to revolutionary tribunals. Within months, however, this ‘revolutionary justice’ was marginalized in favour of the secret police (Cheka) and a policy of terror. This article utilizes the archives of three tribunals, contemporary writings, newspapers and memoirs to examine the tribunals’ investigations and trials, and their impact. It argues that the relative failure of tribunals paved the way for the terror that engulfed Russia by autumn 1918 and laid the foundations of the repressive Soviet state. On 24 November 1917, as part of a radical overhaul of Russia’s legal system, the Bolsheviks established revolutionary tribunals to deal with counter-revolutionary threats, profiteering, speculation, sabotage and other ‘political’ crimes. The definition of counter-revolution was deliberately vague; it could be any thought or action attacking the goals and achievements of the revolution as defined by the Bolsheviks. -

The Russian Revolutions: the Impact and Limitations of Western Influence

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 2003 The Russian Revolutions: The Impact and Limitations of Western Influence Karl D. Qualls Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Qualls, Karl D., "The Russian Revolutions: The Impact and Limitations of Western Influence" (2003). Dickinson College Faculty Publications. Paper 8. https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications/8 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Karl D. Qualls The Russian Revolutions: The Impact and Limitations of Western Influence After the collapse of the Soviet Union, historians have again turned their attention to the birth of the first Communist state in hopes of understanding the place of the Soviet period in the longer sweep of Russian history. Was the USSR an aberration from or a consequence of Russian culture? Did the Soviet Union represent a retreat from westernizing trends in Russian history, or was the Bolshevik revolution a product of westernization? These are vexing questions that generate a great deal of debate. Some have argued that in the late nineteenth century Russia was developing a middle class, representative institutions, and an industrial economy that, while although not as advanced as those in Western Europe, were indications of potential movement in the direction of more open government, rule of law, free market capitalism. Only the Bolsheviks, influenced by an ideology imported, paradoxically, from the West, interrupted this path of Russian political and economic westernization. -

Socialism in Europe and the Russian Revolution India and the Contemporary World Society Ofthefuture

Socialism in Europe and II the Russian Revolution Chapter 1 The Age of Social Change In the previous chapter you read about the powerful ideas of freedom and equality that circulated in Europe after the French Revolution. The French Revolution opened up the possibility of creating a dramatic change in the way in which society was structured. As you have read, before the eighteenth century society was broadly divided into estates and orders and it was the aristocracy and church which controlled economic and social power. Suddenly, after the revolution, it seemed possible to change this. In many parts of the world including Europe and Asia, new ideas about individual rights and who olution controlled social power began to be discussed. In India, Raja v Rammohan Roy and Derozio talked of the significance of the French Revolution, and many others debated the ideas of post-revolutionary Europe. The developments in the colonies, in turn, reshaped these ideas of societal change. ian Re ss Not everyone in Europe, however, wanted a complete transformation of society. Responses varied from those who accepted that some change was necessary but wished for a gradual shift, to those who wanted to restructure society radically. Some were ‘conservatives’, others were ‘liberals’ or ‘radicals’. What did these terms really mean in the context of the time? What separated these strands of politics and what linked them together? We must remember that these terms do not mean the same thing in all contexts or at all times. We will look briefly at some of the important political traditions of the nineteenth century, and see how they influenced change. -

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation J. MICHAEL WALLER "They write I'm the mafia's godfather. It was Vladimir Ilich Lenin who was the real organizer of the mafia and who set up the criminal state." -Otari Kvantrishvili, Moscow organized crime leader.l "Criminals Nave already conquered the heights of the state-with the chief of the KGB as head of a mafia group." -Former KGB Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin.2 Introduction As the United States and Russia launch a Great Crusade against organized crime, questions emerge not only about the nature of joint cooperation, but about the nature of organized crime itself. In addition to narcotics trafficking, financial fraud and racketecring, Russian organized crime poses an even greater danger: the theft and t:rafficking of weapons of mass destruction. To date, most of the discussion of organized crime based in Russia and other former Soviet republics has emphasized the need to combat conven- tional-style gangsters and high-tech terrorists. These forms of criminals are a pressing danger in and of themselves, but the problem is far more profound. Organized crime-and the rarnpant corruption that helps it flourish-presents a threat not only to the security of reforms in Russia, but to the United States as well. The need for cooperation is real. The question is, Who is there in Russia that the United States can find as an effective partner? "Superpower of Crime" One of the greatest mistakes the West can make in working with former Soviet republics to fight organized crime is to fall into the trap of mirror- imaging. -

HPSCI Testimony – Steve Hall I'm Happy to Be with You Here Today To

HPSCI Testimony – Steve Hall I’m happy to be with you here today to share my thoughts on Vladimir Putin’s Russia, gleaned from working in the CIA’s Clandestine Service for over 30 years. During my time at CIA, from when I started out as a line case officer through when I retired in 2015 as a member of the Senior Intelligence Service, most of my time and efforts were focused on Russia. I retired as the Chief of Central Eurasia Division, responsible for managing CIA’s Russian operations worldwide. I am not a trained Russian historian, nor am I an analyst. Rather, my views on Putin’s Russia come from my experiences as a former intelligence officer, and I believe this is an important perspective. Here’s why. I am often asked for my thoughts on who Putin really is, what makes him tick, how he thinks, is he really that much of a threat. My best response is that Vladimir Putin is first and foremost a Chekist, whose primary goal is the weakening of democracy in the United States and the West. The Cheka was the Lenin-era secret police, the precursor to the KGB – of which Putin was a member – as well as to the modern day Russian intelligence services. It was the Cheka and its successors that built and ran the Soviet system of concentration camps, the Gulag. It was the Cheka that executed thousands of its own citizens in the basement of the Lubyanka, its headquarters in Moscow. The history of the Russian intelligence services is one of unalloyed brutality. -

Comparing Terrors: State Terrorism in Revolutionary France and Russia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 Comparing Terrors: State Terrorism in Revolutionary France and Russia Anne Cabrié Forsythe College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Forsythe, Anne Cabrié, "Comparing Terrors: State Terrorism in Revolutionary France and Russia" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626669. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-f7fy-7w09 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparing Terrors: State Terrorism in Revolutionary France and Russia Anne Cabrie Forsythe Richmond, Virginia Bachelors of Arts, Mary Baldwin College, January 2006 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Lyon G. Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary January 2011 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Anne Cabrie Forsythe Approved by the Committee, December 2010 Committee Ch&fr Associate Professor Gail M. Bossenga, History The College of William and Mary James Pinckney Harrison Professor Frederick C. Corney, History The College of William and Mary Professor Carl J. Strikwerda, History Dean of the Faculty of Arts & Sciences The College of William and Mary n4~ Associate Professor Hiroshi Kitamura, History The College of William and Mary ABSTRACT PAGE This paper compares how the National Convention and the Sovnarkom were able to declare terror and how they operated each terror in terms of their definition of revolutionary justice. -

Senior Scholars Interwar Europe Fall 2019 Week 9

10/27/19 Stalinism in the Soviet Union Senior Scholars: Interwar Europe: • Developments since Bolshevik Revolution and end of Civil War WorkinG Out Modernity • Shift in agricultural and economic policy that began with First in the Midst of Crisis Five Year Plan (1928-32) • Stalin’s efforts to eliminate all possible rivals in society, state, Fall 2019 and party – purges of 1930s Prof. Kenneth F. Ledford [email protected] • Foreign policy and shifting attitude of Soviet Union to western 368-4144 democracies and to rise of fascism DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY HISTORY DEPARTMENT HISTORY DEPARTMENT Stalinism and the Soviet Union Stalinism and the Soviet Union Stalinism and the Soviet Union • Bolsheviks consolidated their now position after November • “War Communism • War Communism 1917 only after 4-5 years of bitter struggle – Political aspect • Structure of Government – Major and many-facetted Civil War – Economic aspect – Council of People’s Commissars – Intervention by Allies – Chairman, Vladimir Lenin – War with Poland – Commissar of National Minorities, Josef Stalin (Dzhugashvili) HISTORY DEPARTMENT HISTORY DEPARTMENT HISTORY DEPARTMENT Stalinism and the Soviet Union • Vladimir Lenin (Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov) – Born 1870 Simbirsk – Son of state official (school inspector) – Studied law at University of Kazan – In 1887, his elder brother, Alexander, was executed at age 21 for plotting to assassinate Tsar Alexander III – Became Marxist rather than Populist – Imprisoned 1896, Siberian exile for 3 years, then to Switzerland – Published Social -

The Okhrana and the Cheka: Continuity and Change

The Okhrana and the Cheka: Continuity and Change A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Amanda M. Ward August 2014 © 2014 Amanda M. Ward. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Okhrana and the Cheka: Continuity and Change by AMANDA M. WARD has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Steven M. Miner Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT WARD, AMANDA M., M.A., August 2014, History The Okhrana and the Cheka: Continuity and Change Director of Thesis: Steven M. Miner The most notorious aspect of the Soviet Union was its culture of secret policing that, through a series of state security agencies, carried out mass arrests, deportations, and executions. Since the collapse of the socialist state and the opening of the Soviet archives, the historical community has only begun to understand the full extent of crimes committed at the hands of the Cheka, and its successors, the OGPU, NKVD, and KGB. Yet, after tracing this repression to its origins, historical evidence indicates that Imperial Russia first cultivated this culture of secret policing and introduced many of the policing techniques the Bolsheviks later implement and further perfected. By the turn of the 20th century, the Okhrana – the Tsarist secret police – developed into a highly effective political police force which was, by and large, quite successful in penetrating underground revolutionary organizations, including Lenin’s Bolshevik party. -

Female Prisoners in Stalin's GULAG

Entremons. UPF Journal of World History. Número 10 (Setembre 2019) Nasha VEJ Female prisoners in Stalin’s GULAG – Conditions and survival strategies ■ Article] ENTREMONS. UPF JOURNAL OF WORLD HISTORY Universitat Pompeu Fabra | Barcelona Número 10 (Setembre 2019) www.entremons.org Female prisoners in Stalin’s GULAG – Conditions and survival strategies Nasha VEJ Master’s degree in History from the University of Southern Denmark [email protected] Abstract This article examines the conditions of female prisoners of GULAG labour camps and prisons during Stalin’s era and analyses the culture and survival strategies those prisoners developed. The source material consists mostly of memoirs, as well as a few letters provided by the Memorial Archive from Moscow. Its results show that women were less likely than men to get physically tortured or punished. Instead, psychological torture and humiliation were the most commonly used against female prisoners. However, they were more likely to be the victims of sexual assault, by either guards or fellow inmates. Men and women worked in many of the same fields of labour in the camps, but women were more likely to get light work, and to be genuinely proud of their work effort. The work environment was also the main place where the genders could interact, and build friendships and camp romances. The daily struggles of camp life, like getting enough food and acquiring light work, became the main focus and chief problem. To overcome the mental and physical hurdles of camp and prison life, they developed a series of survival strategies. These included telling each other stories, singing or reciting poetry. -

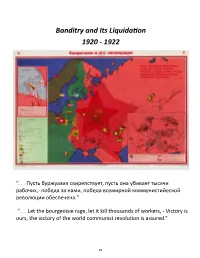

Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic Print, 64 X 102 Cm

Banditry and Its Liquidation 1920 - 1922 “. Пусть буржуазия свирепствует, пусть она убивает тысячи рабочих,- победа за нами, победа всемирной коммунистийеской революции обеспечена.” “. Let the bourgeoisie rage, let it kill thousands of workers, - Victory is ours, the victory of the world communist revolution is assured.” 62 Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic print, 64 x 102 cm. Compilers: A. N. de-Lazari and N. N. Lesevitskii Artist: S. R. Zelikhman Historical Background and Thematic Design The Russian Civil War did not necessarily end with the defeat of the Whites. Its final stage involved various independent bands of partisans and rebels that took advantage of the chaos enveloping the country and contin- ued to operate in rural areas of Ukraine, Tambov Province, the lower Volga, and western Siberia, where Bol- shevik authority was more or less tenuous. Their leaders were by and large experienced military men who stoked peasant hatred for centralized authority, whether it was German occupation forces, Poles, Moscow Bol- sheviks, or Jews. They squared off against the growing power of the communists, which is illustrated as series of five red stars extending over all four sectors. The red circle identifies Moscow as the seat of Soviet power, while the five red stars, enlarging in size but diminishing in color intensity as they move further from Moscow, represent the increasing strength of Communism in Russia during the years 1920-22. The stars also serve as symbolic shields, apparently deterring attacking forces that emanate from Poland, Ukraine, and the Volga region. The red flag with the gold emblem of the hammer-and-sickle in the upper hoist quarter, and the letters Р. -

GULAG the Zek People Foreword by Dr

GULAG The Zek people Foreword BY DR. Art Marianne Neerland Soleim The Nazi camp system is a central part of the research, dissemination and education at the Falstad Centre. The Soviet and Nazi camps were closely related. The two systems were established nearly at the same time and on the same continent. There were prisoners who experienced and described the camps in both systems. When you read the stories of those who survived the Gulag or the Holocaust, one is struck by the differences between the experiences of the victims rather than the differences between the two camp systems. Each story has its own unique qualities and each camp resulted in different types of horror for different types of people. In Germany, one could die of cruelty, in Russia of hopelessness. In Auschwitz you could die in the gas chamber, in Kolyma you could freeze to death in the snow. Nearly 30 million people passed through the vast Soviet prison camp system of Gulag in the period from 1917 to 1986. Several millions succumbed to the cold, food shortages and atrocities. Over the years the word “Gulag” has been the same as the system of slave labour in the Soviet Union, in all its forms and various camps: labour camps, punishment camps, criminal and political camps, women’s camps, children camps and transitional camps. Among the people who became victims of the Gulag system there were also some of the Soviet prisoners of war who had been in German captivity during the Second World War. Stalin considered all prisoners of war as traitors. -

The Soviet Concept of Law

Fordham Law Review Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 1 1938 The Soviet Concept of Law Vladimir Gsovski Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Vladimir Gsovski, The Soviet Concept of Law, 7 Fordham L. Rev. 1 (1938). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol7/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Soviet Concept of Law Cover Page Footnote Assistant in Foreign law, Library of Congress, Washington, D. C. The writer considers it to be his pleasant duty to express deep appreciation of the valuable guidance of Professor Walter B. Kennedy of Fordham law School in the preparation of this paper. Thanks to his generous advice and hearty cooperation the explanation of an intricate matter was brought before the American reader. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol7/iss1/1 FORDHAM LAW REVIEW VOLUME VII 1938 WOOLWORTH BUILDING NEW YORK 1938 Copyright 1938 By Fordham University Printed in U. S. A. The Heffernan Press Worcester, Mass., U. S. A. TABLE OF LEADING ARTICLES-AUTHORS FIDAN, IAnlTO.x R. The Scope of Mortgage Liens on Fixtures and Personal Property in New York ................................ 331 GsovsKI, VLADIMIR. The Soviet Concept of Law ...................