There Ought to Be a Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

The Demolished Man Free

FREE THE DEMOLISHED MAN PDF Alfred Bester | 256 pages | 08 Jul 1999 | Orion Publishing Co | 9781857988222 | English | London, United Kingdom Demolition Man (film) - Wikipedia Demolition Man is a American science fiction action film directed by Marco Brambilla in his directorial debut. Stallone is John Spartan, a risk- taking police officer, who has a reputation The Demolished Man causing destruction The Demolished Man carrying out his work. After a failed attempt to rescue hostages from evil crime lord Simon Phoenix, The Demolished Man are both sentenced to be cryogenically frozen in Phoenix is thawed for a parole hearing inbut escapes. Society has changed and all crime has seemingly been eliminated. Unable to deal with a criminal as dangerous as Phoenix, The Demolished Man authorities awaken Spartan to help capture him again. The story makes allusions to many other works including Aldous Huxley 's dystopian novel Brave New World[6] and H. Wells 's The Sleeper Awakes. The film was released in the United States on October 8, Inpsychopathic career criminal The Demolished Man Phoenix kidnaps a busload of hostages and takes refuge in an abandoned building. LAPD Sergeant John Spartan runs a thermal scan of the building; finding no trace of the hostages, he leads an The Demolished Man assault to capture Phoenix. Phoenix sets off explosives to destroy the building; the hostages' corpses are later found in the rubble, and Phoenix claims Spartan knew about them and attacked anyway. Both men are sentenced to lengthy terms in the city's new "California Cryo-Penitentiary", a prison in which The Demolished Man are cryogenically frozen and exposed to subliminal rehabilitation techniques. -

Cartoon and the Cult of Reduction

Forced Perspectives: Cartoon and The Cult Of Reduction MARTINE LISA COROMPT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (by creative work and dissertation) August 2016 School of Art Faculty Of The Victorian College Of The Arts The University of Melbourne 2 FIG 1 Corompt, Martine Torrent – the endless storm 2015 still from the digital animation 3 4 ABSTRACT Summary Commencing with caricature and reductive imaging techniques, this research explores parallel tendencies evident within broader culture. The thesis argues this reductive predisposition became broader and more prominent during Modernism, the digital revolution of the 1990s, and is strongly manifest within various aspects of contemporary art and culture. Theorized as the ‘Cult of Reduction’ this tendency is both a cultural condition, and a studio methodology employed to create two dimensional projected animation and digital prints. Abstract Beginning with pictorial caricature as a historical predecessor to animation, the research attempted to find in caricature a meaningful methodology to provide a framework for two-dimensional animation. Incorporating digital processes with drawing and installation, reduction was understood and examined pictorially, temporally and materially. The thesis project considered caricature as a means of exploring pictorial representation as reduction, but soon recognized reduction had more broad implications, and parallel examples were discovered in areas such as economics, ecology lifestyle ideologies, as well as Fine art and design. While pictorial reduction was most obvious within Modernism, it also was resonant in less obvious ways within the digital art revolution of the 1990’s. It has been prevalent again in contemporary art as a ‘reductivist practice’ recognized by Mike Kelley’s essay ‘Foul Perfection: Thoughts on Caricature’ (1989). -

Stallone Fights Studio's Accounting Methods

Business Valuations: Stallone Fights Studio’s Accounting Methods Accounting issues take center stage in a recent dispute involving Sylvester Stallone's production company, Rogue Marble, and Warner Bros. Entertainment. The lawsuit charges Warner Bros. with breach of contract, unfair business practices and accounting fraud in connection with the revenues from the 1993 movie Demolition Man. Stallone seeks "full accounting" of revenues from the film, plus interest and damages. The suit doesn't yet specify damages, because Rogue Marble isn't "presently aware of the exact amounts of damages resulting" from the studio's alleged wrongdoing. However, the Oscar-nominated actor, writer and director — who's famous for his roles as Rocky Balboa and John Rambo — has a bigger fight in mind: His lawsuit alleges that "motion picture studios are notoriously greedy." And he wants them to account in a timely and open manner for amounts owed to actors, writers and filmmakers that are contingent on a film's performance. Here are the details of this high-profile case, along with an explanation of how its lessons about contingent consideration extend beyond Hollywood. Case Facts In 1992, Warner Bros. entered into an artist loan-out agreement with Rogue Marble for the services of Sylvester Stallone in Demolition Man, a sci-fi action film that also starred Wesley Snipes and Sandra Bullock. The loan-out agreement granted Rogue Marble certain percentages of the film's total defined gross after the amount exceed certain levels. Specifically, the contract granted: 15% of the gross when it exceeded $125 million, 17.5% when it exceeded $200 million, and 20% when it exceeded $250 million. -

Computer Algorithms As Persuasive Agents: the Rhetoricity of Algorithmic Surveillance Within the Built Ecological Network

COMPUTER ALGORITHMS AS PERSUASIVE AGENTS: THE RHETORICITY OF ALGORITHMIC SURVEILLANCE WITHIN THE BUILT ECOLOGICAL NETWORK Estee N. Beck A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Committee: Kristine Blair, Advisor Patrick Pauken, Graduate Faculty Representative Sue Carter Wood Lee Nickoson © 2015 Estee N. Beck All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair, Advisor Each time our students and colleagues participate online, they face invisible tracking technologies that harvest metadata for web customization, targeted advertising, and even state surveillance activities. This practice may be of concern for computers and writing and digital humanities specialists, who examine the ideological forces in computer-mediated writing spaces to address power inequality, as well as the role ideology plays in shaping human consciousness. However, the materiality of technology—the non-human objects that surrounds us—is of concern to those within rhetoric and composition as well. This project shifts attention to the materiality of non-human objects, specifically computer algorithms and computer code. I argue that these technologies are powerful non-human objects that have rhetorical agency and persuasive abilities, and as a result shape the everyday practices and behaviors of writers/composers on the web as well as other non-human objects. Through rhetorical inquiry, I examine literature from rhetoric and composition, surveillance studies, media and software studies, sociology, anthropology, and philosophy. I offer a “built ecological network” theory that is the manufactured and natural rhetorical rhizomatic network full of spatial, material, social, linguistic, and dynamic energy layers that enter into reflexive and reciprocal relations to support my claim that computer algorithms have agency and persuasive abilities. -

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This List Was Created to Make It Easier for Customers to Figure out What Type of NVRAM They Need for Each Machine

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This list was created to make it easier for customers to figure out what type of NVRAM they need for each machine. Please consult the product pages at www.pinitech.com for each type of NVRAM for further information on difficulty of installation, any jumper changes necessary on your board(s), a diagram showing location of the RAM being replaced & more. *NOTE: This list is meant as quick reference only. On Williams WPC and Sega/Stern Whitestar games you should check the RAM currently in your machine since either a 6264 or 62256 may have been used from the factory. On Williams System 11 games you should check that the chip at U25 is 24-pin (6116). See additional diagrams & notes at http://www.pinitech.com/products/cat_memory.php for assistance in locating the RAM on your board(s). PLUG-AND-PLAY (NO SOLDERING) Games below already have an IC socket installed on the boards from the factory and are as easy as removing the old RAM and installing the NVRAM (then resetting scores/settings per the manual). • BALLY 6803 → 6116 NVRAM • SEGA/STERN WHITESTAR → 6264 OR 62256 NVRAM (check IC at U212, see website) • DATA EAST → 6264 NVRAM (except Laser War) • CLASSIC BALLY → 5101 NVRAM • CLASSIC STERN → 5101 NVRAM (later Stern MPU-200 games use MPU-200 NVRAM) • ZACCARIA GENERATION 1 → 5101 NVRAM **NOT** PLUG-AND-PLAY (SOLDERING REQUIRED) The games below did not have an IC socket installed on the boards. This means the existing RAM needs to be removed from the board & an IC socket installed. -

Curriculum Vitae William C Carruth

Curriculum Vitae William C Carruth June 10, 2013 General Information University address: College of Motion Picture Arts College of Motion Picture Arts University Center Building A3100 Florida State University Tallahassee, Florida 32306-2350 Phone: 888/644-7728 E-mail address: [email protected] Professional Preparation 1969 Master's Degree, LONG BEACH CITY COLLEGE. Major: Psychology. 1967 Bachelor's Degree, Los Angeles City College. Major: Psychology. Postdegree Education and Training 2005 Pro Tools Version 9.0 for Tiger and Version 9.4 for Tiger. 2003 Post Production Techniques, Version 6.4. 2003 Pro Tools Productions Essentials, Version 6.4. 2003 Introduction to Pro Tools, Version 6.4. 1994 Avid Medial Composer 101. Professional Experience 2012–present Laboratory Assistant, College of Motion Picture Arts, Florida State University. 2009–2012 Assistant In (OPS), College of Motion Picture Arts, Florida State University. Vita for William C Carruth 2010–2011 Assistant In, College of Motion Picture Arts, Florida State University. 2005–2008 Assistant In, College of Motion Picture Arts, Florida State University. Teaching Courses Taught MFA Qualifying Project (FIL5962) Thesis Film Support (FIL3971) Advanced Workshop in Area of Specialization (FIL5636-L) Thesis Film (FIL4973) Preproduction and Production Planning (FIL5408) Film Editing (FIL5555-L) Production: Advanced Editing (FIL4567) MFA Thesis Production (FIL5977) Advanced Editing (FIL5568-L) Film Editing (FIL2552) Special Topics (FIL3932) Documentary Filmmaking (FIL3363) Documentary Filmmaking (FIL3231) Film Editing (FIL5257-L) Production: Advanced Editing (FIL4213) Research and Original Creative Work Original Creative Works Films Carruth, W. C. (Sound Editor). (2005). Into The West [TV Movie]. DreamWorks Television. Carruth, W. C. (Sound Editor). (2005). Suzanne's Dairy for Nicholas [TV Movie]. -

Manual Judge Dredd Pinball

Manual Judge Dredd Pinball Bally JUDGE DREDD pinball Planet motor assembly. Reference: 14-7985. Weight: 2 lb. $349.00. Quantity: Please enter a valid quantity. Please enter a valid. Home :: Pinball Machine Manuals :: Bally :: Bally Judge Dredd Manual. Printable version Bally Judge Dredd Manual Instant Download Version. $9.95 (€ 7.46). Shop for pinball parts, spare parts for pinball machines. Judge Dredd Operators Handbook, Bally - original Judge Dredd manual, Bally - original. €29.90 *. Visual Pinball is an amazing pinball emulator using PinMAME. The VPinball DLL This “.psrec” file is simply a recording of sounds instructions. The “.psrec” file. EPROM - new software for your game, U6, L7 Judge Dredd. EPROM Instruction card, Judge Dredd Judge Dredd Reproduction manual. Pinball parts and supplies. Glass · Greg Freres Classic Bally Framed Artwork · Hardware · Homebrew Pinball » · Cabinet Assemblies · Displays · Playfield. Manual Judge Dredd Pinball Read/Download In the manual on page 2-43 it says hswitch 67 is the left ramp entry. The photo pinside.com/pinball/forum/topic/judge-dredd-stays-on-free-play. See. Hd Judge Dredd Pinball Wallpaper Downloads Free/ Judge, Dredd, Pinball, judge judge dredd pinball right flippers won t work, judge dredd pinball manual. 4 piece set of ribbon cables for Bally JUDGE DREDD pinball machine. The PinSound board is compatible with the listed pinball machines. Indiana Jones: The Pinball Adventure. Information about PinSound with Judge Dredd. (1) · Judge Dredd (1) · Jungle Lord (2) · Jurassic Park (1) · Kings of Steel (1) · Lady Luck (1) · Laser War (1) · Last Action Hero (1) · Lethal Weapon 3 (1) · Lights. You will never find more PDF Pinball machines service manuals for this low price! With these service Bally-Midway Judge Dredd Operations & service manual. -

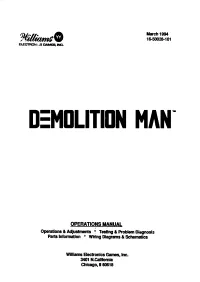

Demolition Man Tm

March 1994 1'(~- 16-50028-101 EU!CTRDNUS flNvlliB, INC. D:MOLITIDN MAN- OPERATIONS MANUAL . .• Operations & Adjustments ~ Testing & Problem Diagnosis Parts Information ° Wiring Diagrams & Schematics Wiiiiams El8ctronlcs Gmms, Inc. 3401 N.Califomla Chicago, 160618 ROM Jumper Chart.----.------. 1 11 M I 2M I 4M ROM I ~ I g~t I Country DIP Switch Chart SW4 Sw5 Sw6 Sw7 Sw8 American On On On On On !=1 On On Off On On Fi:e._~h On On On Off Off German On On On On Off $_Qanish On Off On On On SOLENOID I FLASHER TABLE pollnold Pllt Number Sol. Function - Solenoid Voltage Connectlonl Drive Drive Connedlonl Drive FIMhl1mp Type No. Type xllt Wire Plavfleld BICkbox C.blnlt II Pll!Yfllld B1ckbox Cabinet Color Pll!Yfllld Backbox 01 Ball Release High Power J107·3 OA'.l J130-1 Vio-Bm AE-26-1500 02 Bottom PoDDer H_jg_h Power J107-3 Oen _J_130-2 _.Y!o-Rect AE.:2.3:;800 _Q;t I Auto Plunoer .l:l!rlh Power J107·3 1"17A J130-4 Vio-Ora AE-23-800 04 1.QQ..PODllCll' 1-l!g_h Power J107-3 076 J130-5 Vio-Yel AE·28·1500 05 Oiverter Power Hl!ID Power J107-3 064 J130-6 Vio-Gm A-15943·1 06 Not Used H_jg_h Power OM Vlo-Blu 07 Knocker 1iJ1ID Power J101::! 068 J~ Vlo-Blk ~-23·8CX ...Ql. Not Used Hlah Power 070 Vlo-Grv 09 LaltSlimmbot LowPOWer J107·2 OAA ::JIV-1 ::S:m:;Bi ~200 10 R.Jg_ht Sl.!!!!l._shot Low Power J107·2 OAA J127·3 Bm-Red AE-26-1200 11 Left Jet Bumoer Low Power J107·2 054 J127·4 Bm-O_rg_ AE-26-1200 12 T®- Sllrui_shot Low Power ~07-2 l!'ill J127·5 Bm-Yel AE-26-1200 13 Right Jet Bumjljf Low Power -~07·2 )50 J127-6 Bm-Om AE-26-1200 14 i;Iect Low Power J107-2 )48 J127-7 Bm-Blu AE-26-1200 15 Dlverter Hold Low Power ~07-2 )46 J127·8 Bm·Vlo A-15943-1 16 Not Used Low Power 14- Bm~ 17 Claw Flasher Low Power .J1.U J106-5 J126-1 ,n ;,::>-_l_ Blk·Bm #906J1l #906lll 18 levato(~tor ~- ~26-2 lk· ~ed 14-7993 19 law Motor Le_! ~ 11 • J126-3 lk-4 Jrg 14-7992 1Q. -

Elliot Goldenthal

ELLIOT GOLDENTHAL COMPOSER AWARDS ASCAP Awards (2014) Founders Award ACADEMY AWARD WINNER (2003) FRIDA Best Music, Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2003) FRIDA Best Music, Original Song ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1997) MICHAEL COLLINS Best Music, Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1995) INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE: Best Music, Original Score THE VAMPIRE CHRONICLES GOLDEN GLOBE WINNER (2003) FRIDA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1997) MICHAEL COLLINS Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1995) INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE: Best Music, Original Score THE VAMPIRE CHRONICLES GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2008) ACROSS THE UNIVERSE Best Compilation Soundtrack Album for Motion Picture GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1997) A TIME TO KILL Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1996) BATMAN FOREVER Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD WINNER (2003) FRIDA Soundtrack Composer of the Year WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD WINNER (2003) FRIDA Best Original Soundtrack of the Year 15233 Ventura Boulevard, Suite 200, Sherman Oaks, California 91403 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 Goldenthal Page 1 of 4 ELLIOT GOLDENTHAL COMPOSER AWARDS (continued) WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD NOMINATION (2003) FRIDA Best Original Song Written for a Film WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD NOMINATION (2002) FINAL FANTASY: THE SPIRITS Best Original Song Written for a Film WITHIN MOTION PICTURES OUR SOULS AT NIGHT Ritesh Batra, dir. Netflix A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM Julie Taymor, dir. Londinium Films THE TEMPEST Julie Taymor, dir. Miramax Films PUBLIC ENEMIES Michael Mann, dir. Universal Pictures ACROSS THE UNIVERSE Julie Taymor, dir. Columbia Pictures S.W.A.T. Clark Johnson, dir. Columbia Pictures THE GOOD THIEF Neil Jordan, dir. -

Iris Pattern Recognition with a New Mathematical Model to Its Rotation Detection

Chapter 3 Iris Pattern Recognition with a New Mathematical Model to Its Rotation Detection Krzysztof Misztal, Emil Saeed, Jacek Tabor, and Khalid Saeed Abstract The work deals with the iris pattern recognition as one of the most popular automated biometric ways of individual identification. It is based on the acquired eye images in which we localize the region of interest – the iris. This extremely data-rich biometric identifier is stable throughout human life and well protected as internal part of the eye. Moreover, it is genetic independent, so that we can use it to identify or verify people among huge population. This chapter will present the human vision nature focusing on defects and diseases that change the surface information of the iris. Also will be shown the main stream and the historical background of mathematical research resulting in a new algorithm for automatic iris feature extraction. A special attention is paid to the method devel- oped to detect the iris rotation for accurate success rate under different destructive problems and environmental conditions. The obtained results after using the new mathematical model have proved the algorithm high success rate in iris pattern recognition. K. Misztal (*) AGH University of Science and Technology, Krako´w, Poland e-mail: [email protected] E. Saeed Medical University in Bialystok, Bialystok, Poland J. Tabor Jagiellonian University, Krako´w, Poland K. Saeed AGH University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Physics and Applied Computer Science, Al. Mickiewicza 30, Krako´w PL-30059, Poland e-mail: [email protected] K. Saeed and T. Nagashima (eds.), Biometrics and Kansei Engineering, 43 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-5608-7_3, # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2012 44 K. -

Williams WPC

Williams WPC From PinWiki Click to go back to the Williams solid state repair guides index (http://pinwiki.com/wiki/index.php?title=Williams_Repair_Guides) . Contents 1 Introduction 2 Game List 2.1 WPC (Alphanumeric) 2.2 WPC (Dot Matrix) 2.3 WPC FlipTronics I & II 2.4 WPC DCS Sound 2.5 WPC-S CPU 2.6 WPC-95 CPU 3 Technical Info 3.1 WPC Parts List Lookup 3.2 WPC System Generations 3.2.1 WPC CPU 3.2.2 WPC-S CPU 3.2.3 WPC-95 CPU 3.2.3.1 WPC-95 CPU Factory Modification 3.3 WPC Power/Driver Board Generations 3.3.1 WPC-089 Power/Driver Board 3.3.1.1 WPC Power/Driver Board Layout Errors 3.3.1.1.1 C9 Connection Error 3.3.1.1.2 J122/J124, pin 1 Connected to Board Ground 3.3.2 WPC-95 Power/Driver Board 3.4 WPC Dot Matrix Controller board 3.5 WPC Sound Boards 3.5.1 WPC pre-DCS Sound Board 3.5.2 WPC DCS Sound Board 3.5.3 WPC-95 AV Board 3.6 WPC FlipTronics I & II Boards 3.7 Miscellaneous WPC Boards 3.7.1 WPC 7 Opto Board (A-14977, A-15576, A-15595) 3.7.2 WPC 10 Opto Board (A-15430, A-18159, A-20246) 3.7.3 WPC 16 Opto Board (A-16998, A-17223) 3.7.4 Auxiliary 8-Driver Board (A-16100) 3.7.5 Attack from Mars "Strobe" Board (A-20669) 3.7.6 Trough opto boards 3.7.7 WH2O Chaser Lamp Board (A-15761) 3.7.8 CFTBL Chase Light II Board (A-15541) 3.7.9 High Current Driver Board (C-13963) 3.7.10 Bi-Directional Motor Board (A-15680) 3.7.11 Double Flipper Opto Switch Board (A-15894) 3.7.12 HSII & CFTBL Triac board (A-13088-2) 3.7.13 24 Inch Opto Board (A-15646) 3.7.14 TAF & TAFG High Power Board (A-15139) 3.7.15 TAF & TAFG Extra Flipper Power Supply (A-15416) 3.7.16 The Shadow Five Switch and Diode P.C.B.