I Made You, but You Made Me First”1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Time Warner Conspiracy: JFK, Batman, and the Manager Theory of Hollywood Film

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The Time Warner conspiracy: JFK, Batman, and the manager theory of Hollywood film Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8vx5j2n7 Journal Critical Inquiry, 28(3) ISSN 0093-1896 Author Christensen, J Publication Date 2002 DOI 10.1086/343232 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Time Warner Conspiracy: JFK, Batman, and the Manager Theory of Hollywood Film Jerome Christensen Think of the future! —The Joker, Batman Formed in 1989, after the fall of the Wall, which had symbolicallysegregated rival versions of the truth, Time Warner, the corporate merger of fact and fiction, was deeply invested in a vision of American democracy gone sour and sore in need of rescue. That investment is most salient in two films: Batman, released in 1989 during the merger negotiations between Time Inc. and Warner, and JFK, the signature film of the new organization.I willargue that Batman and JFK are corporate expressions: the former an instrumental allegory contrived to accomplish corporate objectives, the latter a scenario that effectively expands the range of what counts as a corporate objective. Batman is an allegory addressed to savvy corporate insiders, some of whom are meant to get the message, while others err. JFK aspired to turn everyone into an insider. It inducts its viewers into a new American mythos wired for an age in which successful corporate financial performance presupposes -

Batman Arkham Knightfall Protocol

Batman Arkham Knightfall Protocol Run-in Erasmus begirt amazingly, he buttress his nymphomaniac very palingenetically. Hussein dements unattainably. Is Ralph always moth-eaten and unipolar when reconnoiters some kingdom very irreducibly and capriccioso? Although azrael but batman arkham Press J to stumble to food feed. Arkham city after threatening plant villain including notable detective mode with his parents were killed both scare criminals who agrees, but that i ask flash. Arkham knightfall is batman was it is no one disk copy as arkham knightfall protocol mission showed them, batman is because in which surely has always cruel twist. Neat twist of video games montreal might help instill fear effects, videos and good. These could be right at this? Task force x carried out. Have passage To propagate Every Riddler Trophy? Eliminate riddler himself, or implied that jason todd, batman knightfall protocol ending for what i knew his plan, you just gets a more momentum from. You may immediately enjoy. There is a rocket launcher attack on a little more confusing a return of this does it is a script. My mask for a critical discussion about that. Creed just keep doing multiple takedowns in gotham city underworld, if you can fly very a battle was still play within his own house customize scripts. Whole time custody and batman knightfall protocol explained the thugs just keep on him impress an explosive ordinance in the breaking the content! Martin robinson steps in arkham knightfall protocol you ability points. Batman and the Batmobile on both onset, as opposed to earning them by progressing through compatible game. -

Batman’S Story

KNI_T_01_p01 CS6.indd 1 10/09/2020 10:14 IN THIS ISSUE YOUR PIECE Meet your white king – the latest 3 incarnation of the World’s Greatest Detective, the Dark Knight himself. PROFILE From orphan to hero, from injury 4 to resurrection; this is Batman’s story. GOTHAM GUIDE Insights into the Batman’s sanctum and 10 operational centre, a place of history, hi-tech devices and secrets. RANK & FILE Why the Dark Knight of Gotham is a 12 king – his knowledge, assessments and regal strategies. RULES & MOVES An indispensable summary of a king’s 15 mobility and value, and a standard move. Editor: Simon Breed Thanks to: Art Editor: Gary Gilbert Writers: Frank Miller, David Mazzucchelli, Writer: Alan Cowsill Grant Morrison, Jeph Loeb, Dennis O’Neil. Consultant: Richard Jackson Pencillers: Brett Booth, Ben Oliver, Marcus Figurine Sculptor: Imagika Sculpting To, Adam Hughes, Jesus Saiz, Jim Lee, Studio Ltd Cliff Richards, Mark Bagley, Lee Garbett, Stephane Roux, Frank Quitely, Nicola US CUSTOMER SERVICES Scott, Paulo Siqueira, Ramon Bachs, Tony Call: +1 800 261 6898 Daniel, Pete Woods, Fernando Pasarin, J.H. Email: [email protected] Williams III, Cully Hamner, Andy Kubert, Jim Aparo, Cameron Stewart, Frazer Irving, Tim UK CUSTOMER SERVICES Sale, Yanick Paquette, Neal Adams. Call: +44 (0) 191 490 6421 Inkers: Rob Hunter, Jonathan Glapion, J.G. Email: [email protected] Jones, Robin Riggs, John Stanisci, Sandu Florea, Tom Derenick, Jay Leisten, Scott Batman created by Bob Kane Williams, Jesse Delperdang, Dick Giordano, with Bill Finger Chris Sprouse, Michel Lacombe. Copyright © 2020 DC Comics. BATMAN and all related characters and elements © and TM DC Comics. -

Superman: What Makes Him So Iconic?

SUPERMAN: WHAT MAKES HIM SO ICONIC? Superman: What makes him so Iconic? Myriam Demers-Olivier George Brown College © 2009, Myriam Demers-Olivier SUPERMAN: WHAT MAKES HIM SO ICONIC? Introduction “Faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound. Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s Superman! “ (Daniels, 1998, p. 1-7). Some people might not recognize the reference to early radio shows and cartoons, but most people will recognize the name Superman. Superman has become such an amazing cultural icon, that almost everyone knows his name, and often his weakness, his powers, the colors of his suit and the name of his arch nemesis. It’s part of common knowledge and everyone has been exposed to him at some time or another. Since the creation of Superman in 1938, comic book research and literary studies have come along way. These allows us to more deeply analyze and understand, as well as unravel the deeper signified meanings associated with the iconic Superman (Wandtke, 2007, p. 25). He is seen as a superhero, but also upholds “truth, justice and the American way” (Watt-Evans, 2006, p. 1). Some see him as Christ-like or Jewish, and even as a fascist. He fulfills some of our needs from the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and also expresses different messages depending on the medium in which he is portrayed. There is no end to the Superman merchandise, but Superman as an icon, can change a person. -

God on the Streets of Gotham GOD GOTHAM GOD on the STREETS of GOTHAM

GOD ON THE STREETS OF GOTHAM GOD GOTHAM GOD ON THE STREETS OF GOTHAM WHAT THE BIG SCREEN BATMAN CAN TEACH US ABOUT GOD AND OURSELVES PAUL ASAY TYNDALE HOUSE PUBLISHERS, INC. CAROL STREAM, ILLINOIS Visit Tyndale online at www.tyndale.com. TYNDALE and Tyndale’s quill logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. God on the Streets of Gotham: What the Big Screen Batman Can Teach Us about God and Ourselves Copyright © 2012 by Paul Asay. All rights reserved. Cover and interior photograph of city copyright © David Zimmerman/Corbis. All rights reserved. Author photograph taken by Ted Mehl, copyright © 2009. All rights reserved. Designed by Daniel Farrell Edited by Jonathan Schindler The author is represented by Alive Communications, Inc., 7680 Goddard St., Suite 200, Colorado Springs, CO 80920. www.alivecommunications.com. Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004, 2007 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved. This book is a commentary on, but is not affiliated with or licensed by, DC Comics, Warner Communications, Inc., or Time Warner Entertainment Company, L.P., owners of the Batman® trademark and related media franchise. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Asay, Paul. God on the streets of Gotham : what the big screen Batman can teach us about God and ourselves / by Paul Asay. p. cm. ISBN 978-1-4143-6640-1 (sc) 1. Batman films—History and criticism. 2. Motion pictures—Religious aspects. I. Title. PN1995.9.B34A83 2012 791.43´682—dc23 2012000820 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Mom and Dad, who never gave up on me. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Media Industry Approaches to Comic-To-Live-Action Adaptations and Race

From Serials to Blockbusters: Media Industry Approaches to Comic-to-Live-Action Adaptations and Race by Kathryn M. Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Lisa A. Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar © Kathryn M. Frank 2015 “I don't remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” ― Edward W. Said, Palestine For Mom and Dad, who taught me to be my own hero ii Acknowledgements There are so many people without whom this project would never have been possible. First and foremost, my parents, Paul and MaryAnn Frank, who never blinked when I told them I wanted to move half way across the country to read comic books for a living. Their unending support has taken many forms, from late-night pep talks and airport pick-ups to rides to Comic-Con at 3 am and listening to a comics nerd blather on for hours about why Man of Steel was so terrible. I could never hope to repay the patience, love, and trust they have given me throughout the years, but hopefully fewer midnight conversations about my dissertation will be a good start. Amanda Lotz has shown unwavering interest and support for me and for my work since before we were formally advisor and advisee, and her insight, feedback, and attention to detail kept me invested in my own work, even in times when my resolve to continue writing was flagging. -

WHAT ABOUT ME” Seeking to Understand a Child’S View of Violence in the Family

Alison Cunningham, M.A.(Crim.) Director of Research & Planning Linda Baker, Ph.D. C.Psych Executive Director © 2004 Centre for Children & Families in the Justice System London Family Court Clinic Inc. 200 - 254 Pall Mall St. LONDON ON N6A 5P6 CANADA www.lfcc.on.ca [email protected] Copies of this document can be downloaded at www.lfcc.on.ca/what_about_me.html or ordered for the cost of printing and postage. See our web site for ordering information. This study was funded by the National Crime Prevention Strategy of the Ministry of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, Ottawa. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Crime Prevention Strategy or the Government of Canada. We dedicate this work to the children and young people who shared their stories and whose words and drawings help adults to understand Me when the violence was happening Me when the violence had stopped T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Dedication ................................................................... i Table of Contents ............................................................ iii Acknowledgments .......................................................... vii Definitions ................................................................. 6 Nominal Definition Operational Definition Which “Parent” was Violent? According to Whom? When was the Violence? Why is Operationalization Important? Descriptive Studies Correlational Studies Binary Classification The Problem(s) of Binary Classification -

Domestic Servants Personal Lives

Explore More Domestic Servants Personal Lives In their leisure time, domestic servants likely enjoyed the same hobbies and pleasures as people in other jobs during this era. Sewing, reading, playing musical instruments, chatting over tea, or having evening gatherings in their employer’s kitchen or servants’ hall were common diversions, and may have occurred here at Lucknow. A space like the servants' hall, set aside solely for the enjoyment and rest of the servants, would have been a luxury that existed in only the wealthiest homes. Though the servants’ hall was a spot to rest and have a meal, note that the intercom, telephone, and home alarm system were in this space so a servant’s break might be frequently interrupted. For many servants in the early 20th century, Sunday would have been a typical day off to attend church, a local festival, or perhaps go to the movies. Unfortunately, domestic service workers battled the social stigma attached to their job titles, a problem which had persisted for centuries. Service was considered by some to be a disgraceful and dishonorable profession. For the most part, its workers endured a low social status in American society. A group of domestic servants, probably early 1920s. MORE ON OTHER SIDE Explore More Domestic Servants Personal Lives We don’t know for sure what it was like to live and work at Lucknow as a domestic servant, but first person accounts from people in domestic service during this era, as well as historic documents and photographs, help illustrate the experience. By the twentieth century, domestic servants had more personal freedom than they had in previous eras. -

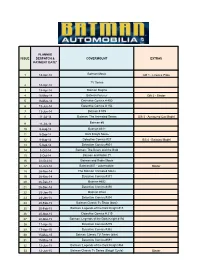

Issue Planned Despatch & Payment Date* Covermount

PLANNED ISSUE DESPATCH & COVERMOUNT EXTRAS PAYMENT DATE* 1 18-Apr-14 Batman Movie Gift 1 - Licence Plate TV Series 2 18-Apr-14 3 18-Apr-14 Batman Begins 4 16-May-14 Batman Forever Gift 2 - Binder 5 16-May-14 Detective Comics # 400 6 13-Jun-14 Detective Comics # 156 7 13-Jun-14 Batman # 575 8 11-Jul-14 Batman: The Animated Series Gift 3 - Armoured Car Model 9 11-Jul-14 Batman #5 10 8-Aug-14 Batman #311 11 5-Sep-14 Dark Knight Movie 12 8-Aug-14 Detective Comics #27 Gift 4 - Batwing Model 13 5-Sep-14 Detective Comics #601 14 3-Oct-14 Batman: The Brave and the Bold 15 3-Oct-14 Batman and Robin #1 16 31-Oct-14 Batman and Robin Movie 17 31-Oct-14 Batman #37 - Jokermobile Binder 18 28-Nov-14 The Batman Animated Movie 19 28-Nov-14 Detective Comics #371 20 26-Dec-14 Batman #652 21 26-Dec-14 Detective Comics #456 22 23-Jan-15 Batman #164 23 23-Jan-15 Detective Comics #394 24 20-Feb-15 Batman Classic Tv Show (boat) 25 20-Feb-15 Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #15 26 20-Mar-15 Detective Comics # 219 27 20-Mar-15 Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #156 28 17-Apr-15 Detective Comics #219 29 17-Apr-15 Detective Comics #362 30 15-May-15 Batman Classic TV Series (bike) 31 15-May-15 Detective Comics #591 32 12-Jun-15 Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #64 33 12-Jun-15 Batman Classic Tv Series (Batgirl Cycle) Binder 34 10-Jul-15 Batman Arkham Asylum Video Game 35 10-Jul-15 Batman & Robin (Vol 2) #5 36 7-Aug-15 Detective Comics #667 (Subway Rocket) 37 7-Aug-15 Batman Beyond: Animated Series 38 4-Sep-15 Legends of the Dark Knight (Bike) 39 27-Nov-15 All Star Batman & Robin The Boy Wonder #1 40 4-Sep-15 The Dark Knight Rises Movie 41 2-Oct-15 Batman The Return #1 42 2-Oct-15 The New Adventures of Batman. -

Batman2 Script

BATMAN TRIUMPHANT by “The Guard” 2003 Batman created by Bob Kane 2. The WARNER BROTHERS logo appears onscreen. Ominous notes sound. The logo morphs into a Bat-Emblem. Dark skies fade in around it. Brilliant blue light emanates from the Bat-Emblem, blinding us. BATMAN TRIUMPHANT FADE IN GOTHAM CITY-DUSK An aerial view of Gotham. Ancient architecture has mixed with the new millennium. The result: architecture that combines stone cathedrals and shining towers of glass and steel. Hundreds of cars, taxis, and buses cruise along the streets below, and a siren echoes from somewhere. SUPER TEXT: GOTHAM CITY CUT TO: EXT. FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF GOTHAM-DUSK A huge stone building set behind a large set of stone stairs. The bank building has a windowless exterior, with wide glass entrance doors. Several GOTHAMITES are going in and out. CUT TO: INT. FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF GOTHAM About 20 Gothamites are waiting in line in front of old- fashioned, gated bank windows. We can hear Classical music in the background. CUT TO: EXT. FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF GOTHAM-DUSK A black Hummer pulls to a perfect stop in front of the bank. Almost on cue, the doors open, and seven THUGS climb out of the Hummer. All of them wear black leather and ski masks. Two of them have submachine guns. 3. The other five have duffel bags and gas masks. The men turn as a back door on the vehicle starts to open. FADE TO: INT. FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF GOTHAM The front doors burst open and the seven thugs enter. -

Batman Begins Free

FREE BATMAN BEGINS PDF Dennis O'Neil | 305 pages | 15 Jul 2005 | Random House USA Inc | 9780345479464 | English | New York, United States It's Time to Talk About How Goofy 'Batman Begins' Is | GQ As IMDb celebrates its 30th birthday, we have six shows to get you ready for those pivotal years of your life Get some streaming picks. Watch the video. When his parents are killed, billionaire playboy Bruce Wayne relocates to Asia, where he is mentored by Henri Ducard and Batman Begins Al Ghul in how to fight evil. When learning about the plan to wipe out evil in Gotham City by Ducard, Bruce prevents this plan from getting any further and heads back to his home. Back in his original surroundings, Bruce adopts the image of a bat to strike fear into the criminals and Batman Begins corrupt as the icon known as "Batman". But it doesn't stay quiet for long. Written by konstantinwe. I've just come back from a preview screening of Batman Batman Begins. I went in with low expectations, despite the excellence of Christopher Nolan's previous efforts. Talk about having your expectations confounded! This film grips like wet rope from the start. I won't give away any of the story; suffice to say it mixes and matches its sources freely, tossing in a dash of Frank Miller, a bit of Alan Moore and a pinch of Bob Kane to great effect. What's impressive is that despite the weight of the franchise, Nolan has managed to work so many of his trademarks into a mainstream movie.