A Special Report on Concussion in Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BC485779 S 3K 21 LEDDURE RASHAD BAUMAN and Case No 22 VERONICA BAUMAN, His Wife; JOHN W

1 GIRARDI I KEESE FILED SUPERIORCOURTOFCAUFOR.NIA 2 THOMAS V. GIRARDI, Bar No. 36603 COUNTVOFL05A.NGELES 1126 Wilshire Boulevard 3 Los Angeles, California 90017 MAY 3 1 2012 Telephone: (213)977-0211 4 ;e.ExecutiveOflicer/Cleric Facsimile: (213)481-1554 ., Deputy 5 '»Wesley RUSSOMANNO & BORRELLO, P.A. 6 Herman Russomanno (FloridaBar No. 240346)Pro Hac Vice ApplicationForthcoming 7 Robert Borrello (Florida BarNo. 764485) Pro Hac Vice Appliication Forthcoming 150 West Flagler Street - PH 2800 8 Miami, FL 33130 9 Telephone: (305) 373-2101 Facsimile: (305) 373-2103 10 11 GOLDBERG, PERSKY & WHITE, P.C. Jason E. Luckasevic (Pennsylvania Bar No. 85557) Pro Hac Vic^ Application Forthcoming 12 1030 Fifth Avenue 13 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 Telephone: (412) 471-3980 14 Facsimile: (412) 471-8308 XI m 15 Attorneysfor Plaintiffs *3s ^ f> fj *> ?0£3E3>35?"5> {/} to *3s _ "» 16 J? S * O 17 ^ 0"> o oa 9« »-«•oS•*» cj53 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF' CALIFORNIA to v*- O- *o »— ti fv) «o r- 18 o £5 m o CD ». COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES o o S ^ 19 ;• 01 m 20 a w BC485779 s 3K 21 LEDDURE RASHAD BAUMAN and Case No 22 VERONICA BAUMAN, his wife; JOHN W. BEASLEY and PATRICIA BEASLEY, his wife; 23 JEFF BLACKSHEAR; CARLTON BREWSTER; 2 jg*o trt a> 3> — • JOSEPH CAMPBELL; FRED H. COOK HI; COMPLAINT FOR DAMAGES 3? si 8! < 24 COREY V. CROOM; PATRICK CUNNINGHAM ro -k ^ *•* o> 3>- 3C ^- 3E «• fi? a» »- 25 and DEBBIE CUNNINGHAM, his wife; 20 2t> cn rn •» «* TIMOTHY DANIEL; ENNIS R. DAVIS, II; DEMAND FOR JURY IrI^ 2 <= 2 v> o* o oo • "v o en 26 MICHAEL DAVIS and GWENDOLYN DAVIS, o o ae -a O •-* -J* ^J his wife; KEVIN DEVINE; ARNOLD FIELDS ~v. -

Illegal Procedure

Wendel: Illegal Procedure Published by SURFACE, 1990 1 Syracuse University Magazine, Vol. 6, Iss. 3 [1990], Art. 6 https://surface.syr.edu/sumagazine/vol6/iss3/6 2 Wendel: Illegal Procedure "Payton's perfect for Busch's 'Know When to former Iowa running back Ronnie Harmon (now Say When' campaign," Ki les says, taking a quick with the Buffalo Bills) and Paul Palmer, the 1986 glance at his side mirror and then cutting for day Heisman Trophy runner-up from Temple. light. "He doesn't drink himself and he's already Among those who testified at the Walters-Bloom out there making appearances on the race circuit." trial was Michael Franzese, a captain in the With a B.A. (1975) and law degree (1978) Colombo crime family, who said he invested from Syracuse University, Kiles is one of a half $50,000 in the agents' business and gave Walters dozen SU alumni who are deal-makers in the permission to use his name to enforce contracts world of sports. Kiles, once the agent for Orange wi th players. men football stars Bill Hurley and Art Monk, has Even though some, most notably NCAA a practice with two offices on M Street in Wash executive director Dick Schultz, said the convic ington. He represents several members of the tion sent a clear message to players and agents National Football League Redskins, and works alike, others maintain the court case merely with companies that want to serve as corporate scratched the surface of the sleazy deals cur sponsors for the 1992 Olympics and 1994 soccer From the public's rently going down in sports. -

Nfl) Retirement System

S. HRG. 110–1177 OVERSIGHT OF THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE (NFL) RETIREMENT SYSTEM HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 18, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–327 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska, Vice Chairman JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota TRENT LOTT, Mississippi BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas BILL NELSON, Florida OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine MARIA CANTWELL, Washington GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada MARK PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JIM DEMINT, South Carolina CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri DAVID VITTER, Louisiana AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARGARET L. CUMMISKY, Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel LILA HARPER HELMS, Democratic Deputy Staff Director and Policy Director CHRISTINE D. KURTH, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel PAUL NAGLE, Republican Chief Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on September 18, 2007 .................................................................... -

Framing and News Coverage of the NFL's Concussion Lawsuit in The

A Hit to the Head: Framing and News Coverage of the NFL’s Concussion Lawsuit in The New York Times and ESPN ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Honors Tutorial College Ohio University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from The Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism ____________________________________ By Kaitlin Coward May 2018 2 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism __________________________ Dr. Aimee Edmondson Associate Professor, Journalism Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism ___________________________ Cary Frith Interim Dean, Honors Tutorial College 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would never have been possible without Dr. Aimee Edmondson and all the guidance she provided throughout the past year. She worked to guide me through my research, keep me calm when things got stressful and push me to make my writing the best it could be. I truly do not know how this project would have to come to be without her. Several other people have helped me along the process as well, including Dr. Bernhard Debatin, who initially approved the idea behind this. I also want to give a special shoutout to everyone in The Post newsroom for listening to me ramble about concussions and letting me talk people’s ears off about social responsibility theory and more. You all made it so I was consistently excited about my project and gave me the belief that I could actually do this. I also want to thank those of you who took the time to read through and copy edit my chapters. -

(Expert Ties Ex-Player\222S Suicide to Brain Damage

Expert Ties Ex-Player’s Suicide to Brain Damage - New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/18/sports/football/18waters.html?ei=5... January 18, 2007 Expert Ties Ex-Player’s Suicide to Brain Damage By ALAN SCHWARZ Since the former National Football League player Andre Waters killed himself in November, an explanation for his suicide has remained a mystery. But after examining remains of Mr. Waters’s brain, a neuropathologist in Pittsburgh is claiming that Mr. Waters had sustained brain damage from playing football and he says that led to his depression and ultimate death. The neuropathologist, Dr. Bennet Omalu of the University of Pittsburgh, a leading expert in forensic pathology, determined that Mr. Waters’s brain tissue had degenerated into that of an 85-year-old man with similar characteristics as those of early-stage Alzheimer’s victims. Dr. Omalu said he believed that the damage was either caused or drastically expedited by successive concussions Mr. Waters, 44, had sustained playing football. In a telephone interview, Dr. Omalu said that brain trauma “is the significant contributory factor” to Mr. Waters’s brain damage, “no matter how you look at it, distort it, bend it. It’s the significant forensic factor given the global scenario.” He added that although he planned further investigation, the depression that family members recalled Mr. Waters exhibiting in his final years was almost certainly exacerbated, if not caused, by the state of his brain — and that if he had lived, within 10 or 15 years “Andre Waters would have been fully incapacitated.” Dr. -

FORG 325 Sports

FORG 325 Sports Spring 2019 • MWF 10-10:50 • Classroom: Instructor: John Alcorn • [email protected] • Seabury 110 Office hours: MWF 8:30-9:30 and 1:00-2:00; and by appointment An introduction to social science of sports. We will focus on motivations and behaviors in sports organizations and markets. We will compare and contrast collegiate and professional sports; individual and team sports; and sports contests among nation-states. Specific topics are: nature & nurture in athletic prowess, stakeholders (athletes, fans, owners, media, and sponsors), dysfunctions (bias, corruption, discrimination, doping, & violence), & governance (informal honor codes, and the human element in refereeing). An overarching question is: What are sports for? We will review answers from various disciplines in the liberal arts, and will try and develop our own. Students will conduct policy debates. Topics of debates will include: pay-for-play for collegiate athletes, performance-enhancing drugs, and subsidies for stadiums, and refereeing by technology. There will be guest visits by experts from the field, to be scheduled. We will have occasional discussions of ‘sports in the news’ (public controversies about our topics) in class and by forum posts at our course intranet (Moodle site). There will be workshops with educational technology specialists, to be scheduled. Enrollment is limited to 15 students. Course requirements: • Four papers or media projects. Papers should be 1,500 words each. Media projects may be blogs, podcasts, or videos. • Two presentations (in rotation) about the assigned materials. • A policy debate. • Class participation, consisting in regular attendance and discussion, and in attendance at supplementary public lectures, which are listed on the syllabus. -

Darrell Dess

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 28, No. 2 (2006) WHEN HAVING A BETTER RECORD DIDN'T MEAN HOME FIELD ADVANTAGE, Part Two By Andy Piascik With the NFL-AFL merger in 1966 and the advent of the Super Bowl, pro football's postseason began to grow larger. Neither the NFL or AFL addressed the long-standing problem of how better to determine the home team in their respective Championship Games, however. In fact, almost another decade would go by until necessary changes were made. Instead, both leagues continued with the rotation system that had ruled pro football's postseason since 1933. And as happened so many times previously, the teams that finished with the best regular season record in both leagues in 1966, the Packers and the Chiefs, had to go on the road in the title games. Bucking the odds clearly established over the previous 33 years, both won. Even when the NFL realigned in 1967 and enlarged the playoffs, the same system was left intact. Again, evidence that something was amiss was immediately apparent. That year, the Rams finished 11-1-2 and won the Coastal Division of the Western Conference on the basis of a head to head tie-breaker over the Colts, who also finished 11-1-2. In the West's Central Division, meanwhile, the Packers finished first at 9-4-1. Despite their superior record and even though they had beaten Green Bay in their regular season meeting, the Rams had to travel to Wisconsin to play the Western Conference Championship Game. After beating the Packers two weeks earlier in Los Angeles, the Rams lost and went home while the Packers went on to win the Super Bowl. -

The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What Is Being Done to Fix It

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Jessie O'Kelly Freshman Essay Award English 12-1-2019 The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What is Being Done to Fix it Bennett Perkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/englfea Part of the Neurology Commons Citation Perkins, B. (2019). The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What is Being Done to Fix it. Jessie O'Kelly Freshman Essay Award. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/englfea/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jessie O'Kelly Freshman Essay Award by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League 1 The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What is Being Done to Fix it Bennett Perkins University of Arkansas The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League 2 The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What is Being Done to Fix it Football has been a popular sport in America since the 1920s. With the sport being so popular, there are many levels ranging from high school to college to various professional leagues. According to Kathryn Heinze and Di Lu (2017), the National Football League, the most popular professional football league, is the biggest and most powerful sports league in the United States. In 2015, the estimated revenue was $13 billion (Heinze & Lu, 2017). -

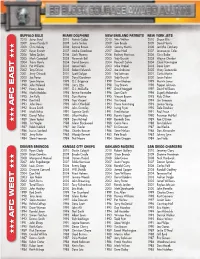

Afc East Afc West Afc East Afc

BUFFALO BILLS MIAMI DOLPHINS NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS NEW YORK JETS 2010 Jairus Byrd 2010 Patrick Cobbs 2010 Wes Welker 2010 Shaun Ellis 2009 James Hardy III 2009 Justin Smiley 2009 Tom Brady 2009 David Harris 2008 Chris Kelsay 2008 Ronnie Brown 2008 Sammy Morris 2008 Jerricho Cotchery 2007 Kevin Everett 2007 Andre Goodman 2007 Steve Neal 2007 Laveranues Coles 2006 Takeo Spikes 2006 Zach Thomas 2006 Rodney Harrison 2006 Chris Baker HHH 2005 Mark Campbell 2005 Yeremiah Bell 2005 Tedy Bruschi 2005 Wayne Chrebet 2004 Travis Henry 2004 David Bowens 2004 Rosevelt Colvin 2004 Chad Pennington 2003 Pat Williams 2003 Jamie Nails 2003 Mike Vrabel 2003 Dave Szott 2002 Tony Driver 2002 Robert Edwards 2002 Joe Andruzzi 2002 Vinny Testaverde 2001 Jerry Ostroski 2001 Scott Galyon 2001 Ted Johnson 2001 Curtis Martin 2000 Joe Panos 2000 Daryl Gardener 2000 Tedy Bruschi 2000 Jason Fabini 1999 Sean Moran 1999 O.J. Brigance 1999 Drew Bledsoe 1999 Marvin Jones 1998 John Holecek 1998 Larry Izzo 1998 Troy Brown 1998 Pepper Johnson 1997 Henry Jones 1997 O.J. McDuffie 1997 David Meggett 1997 David Williams 1996 Mark Maddox 1996 Bernie Parmalee 1996 Sam Gash 1996 Siupeli Malamala 1995 Jim Kelly 1995 Dan Marino 1995 Vincent Brown 1995 Kyle Clifton 1994 Kent Hull 1994 Troy Vincent 1994 Tim Goad 1994 Jim Sweeney AFC EAST 1993 John Davis 1993 John Offerdahl 1993 Bruce Armstrong 1993 Lonnie Young 1992 Bruce Smith 1992 John Grimsley 1992 Irving Fryar 1992 Dale Dawkins 1991 Mark Kelso 1991 Sammie Smith 1991 Fred Marion 1991 Paul Frase 1990 Darryl Talley 1990 Liffort Hobley -

A Sociological Perspective

0 CONFLICT OF INTERESTS IN SPORT AGENCIES AS REFLECTED IN CAMERON CROWE'S JERRY MAGUIRE MOVIE: A SOCIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE RESEARCH PAPER Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by NURUL AHMASIYAH A 320 040 424 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION FACULTY MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2009 1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Cameron Crowe's Jerry Maguire is the drama, comedy, romance and sport movie produced in United States of America. It was released on December, 13th, 1996 by Columbia Tri-Star Pictures in two discs which contained one hundred-thirty nine minutes of duration. It uses English and American Sign Language. In Jerry Maguire, there are some locations in some cities in United States of America, such as Arizona, Atlanta, Dallas, Manhattan, Odessa, Phoenix and also Texas. Thos movie (as an explanation of the author) is just a fictitious story. Before writing the story, the author made a kind of research by talking to businessmen, visiting big office and interviewing the hard workers. After that, a friend of him showed the picture from The Los Angeles Time, it was an old photo of a sport agent and a client, two stern-looking men in shirt and sunglasses. During the next view years with the help of sport attorney, Leigh Steinberg, he met and traveled with athletes and sport agents of all kind, and he began to develop the character of Jerry Maguire. Jerry Maguire is the sport agent working for Sport Management International (SMI) with seventy-two clients in his arm. -

2011 Momentum Magazine

2 0 1 0 Year in Review New Online Coach, Parent and Athlete Courses a Huge Hit AAU Mandates Double-Goal Coach® Training for All 50,000 Coaches PCA Trains 45,000 Coaches and Officials for Texas Schools Full-Scale Chicago Office Launched Triple-Impact Competitor™ Scholarship Program Expands Elevating PCA’s Game ooking back on PCA’s amazing 2010, I think las, Sacramento and Chicago, PCA elevated its of the book I just finished – Elevating Your game in 2010. LGame: Becoming a Triple-Impact Competitor What made it possible? (All quotes from – which addresses the question: Elevating Your Game.) How do athletes elevate their game when it matters most? • Effort as a Habit: “A Triple-Impact Competi- tor understands that setbacks are inevitable and From epic partnerships with the Amateur responds to them with renewed effort. He or she Athletic Union and Texas’ University Interscho- understands that success comes from effort over lastic League to the wonderful reception given time.” For the last 11 years PCA staff, board our new online courses, from the growth of our members, trainers and supporters have made ef- national Double-Goal Coach Awards and Triple- fort a habit! Impact Competitor Scholarships to our new model of local expansion now in place in Houston, Dal- • Teachable Spirit: “Having a Teachable Spirit is like being a sponge. A Triple-Impact Com- petitor is sponge-like, hungry to learn, con- stantly on the lookout for ideas, tools, any- thing that will make him or her better.” I once thought the first chapter of the PCA story was “getting smart” (followed by “building in- frastructure” and “going to scale”). -

Eagles by Jersey Number

EAGLES BY JERSEY NUMBER 1 Happy Feller, Nick Mick-Mayer, Tony Franklin, Gary Anderson, Mat Dave Archer, Chris Boniol, Donté Stallworth, Willie Reid, Jeremy McBriar, Cody Parkey, Cameron Johnston Maclin, Dorial Green-Beckham, Shelton Gibson, Josh McCown, 2 Joe Pilconis, Mike Michel, Mike Horan, Dean Dorsey, Steve DeLine, Jalen Reagor David Akers, Matt Barkley, Jalen Hurts 19 Roger Kirkman, Orrin Pape, Jim Leonard, Herman Bassman, Fritz 3 Roger Kirkman, Jack Concannon, Mark Moseley, Eddie Murray, Ferko, Tom Burnette, George Somers, Harold Pegg, Dan Berry, Todd France, Reggie Hodges, Nick Murphy, Mike Kafka, Mark Tom Dempsey, Guido Merkens, Troy Smith, Sean Morey, Carl Sanchez Ford, Michael Gasperson, Brandon Gibson, Mardy Gilyard, Greg Salas, Miles Austin, Paul Turner, Golden Tate, J.J. Arcega-Whiteside 4 Benjy Dial, Max Runager, David Jacobs, Dale Dawson, Bryan Barker, Tom Hutton, Mike McMahon, Kevin Kolb, Stephen Morris, 20 Alex Marcus, John Lipski, Clyde Williams, Howard Bailey, Pete Jake Elliott Stevens, Jim MacMurdo, Henry Reese, Elmer Hackney, Don Stevens, Bibbles Bawel, Jim Harris, Frank Budd, Leroy Keyes, 5 Joseph Kresky, Davey O’Brien, Roman Gabriel, Tom Skladany, John Outlaw, Leroy Harris, Andre Waters, Vaughn Hebron, Brian Dean May, Mark Royals, Jeff Feagles, Donovan McNabb Dawkins 6 Jim MacMurdo, Gary Adams, John Reaves, Spike Jones, Dan 21 James Zyntell, Les Maynard, Paul Cuba, John Kusko, Herschel Pastorini, Matt Cavanaugh, Bubby Brister, Jason Baker, Lee Stockton, Allison White, Chuck Cherundolo, William Boedeker, Johnson,