03 Thor Lake Project DAR Description of Local Communities and Socio-Economic Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Land Claims and the Future of Archaeology in the Northwest Territories, Canada Thomas D

17 Native Land Claims and the Future of Archaeology in the Northwest Territories, Canada Thomas D. Andrews Charles D. Arnnold Elisa J. Hart Margaret M. Bertulli The settlement of comprehensive land claims is ushering in major changes in the manage ment of land and resources in the Northwest Territories, including heritage resources. This chap ter summarizes the progress that has been made in completing land claims, anticipates the impact that the claims will have on the way archaeological research is conducted, and discusses how the Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) is responding to these changes. Suggestions for dealing with the current social and political setting in the design and implementation of archaeological projects are also presented. OUTLINE OF NATIVE LAND CLAIMS IN THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES In the early 1970s, the Government of Canada established a comprehensive claims policy to guide negotiations with Native groups in settling Aboriginal interests in lands that they tradition ally occupied. Although the Northwest Territories has its own legislative assembly and its own bureaucracy to administer most of the business of government, the Government of Canada has the sole responsibility for settling Aboriginal land claims in the Northwest Territories. The Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Territories are the Inuit, the Dene, the Cree, and the Metis. The Inuit include the Inuvialuit of the Beaufort Sea and Amundson Gulf areas of the west ern Arctic, who, in 1984, were the first Aboriginal group in the Northwest Territories to settle a land claim with the Government of Canada (see Figure 1). In May, 1993, the Inuit of the eastern Arctic, an area commonly referred to as “Nunavut” signed a final agreement on a land claim. -

Tłı̨chǫ Łeagia Ts'ı̨ı̨lı̨ Kǫ (TLTK)

Tłıchǫ̨ Łeagia Ts’ıı̨ l̨ ı ̨ Kǫ (TLTK) 2017 Behchokǫ̀ Homelessness Needs Assessment Report of Survey Results March 2018 Funded in part by the Government of Canada's Homelessness Partnering Strategy’s Innovative Solutions to Homelessness The opinions and interpretations in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada E. Huse & Associates Campbell River, BC V9W 2A7 Ph: (250) 895-1775 -- Email: [email protected] 1 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 3 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Purpose of 2017 Behchokǫ̀ Homelessness Needs Assessment and Strategic Solutions Strategy ...... 6 1.2 About Tłı̨chǫ Friendship Centre ......................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Literature Review .................................................................................................................................. 8 Stakeholders ........................................................................................................................................ -

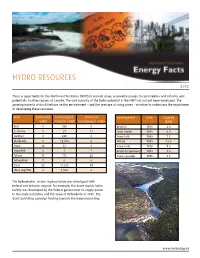

Hydro Energy in The

HYDRO RESOURCES 2012 There is opportunity for the Northwest Territories (NWT) to provide clean, renewable energy to communities and industry, and potentially to other regions of Canada. The vast majority of the hydro potential in the NWT has not yet been developed. The growing impacts of fossil fuel use on the environment – and the pressure of rising prices – continue to underscore the importance of developing these resources. River Developed Undeveloped Proposed Development Date Capacity (MW) Potential (MW) Development (MW) (MW) Bear 0 568 0 Bluefish 1938 3.0 La Martre 0 27 13 Snare Rapids 1948 8.0 Lockhart 0 269 0 Snare Falls 1960 7.5 Mackenzie 0 10,450 0 Taltson 1965 18.0 Snare 30 33 0 Snare Forks 1976 9.0 Snowdrift 0 1 1 Bluefish Expansion 1994 4.0 Taltson 18 172 56 Snare Cascades 1996 4.3 Yellowknife 7 0 0 Total 55 11,520 69 Slave (AB/NT) 0 1,500 0 The hydroelectric system in place today was developed with federal and industry support. For example, the Snare Rapids hydro facility was developed by the federal government to supply power to the Giant Gold Mine and the town of Yellowknife in 1948. The Giant Gold Mine provided funding towards the transmission line. www.nwtenergy.ca In the 1960’s, a hydro plant on the Taltson River was constructed to supply power to the Pine Point Cominco Mine site and the communities of Pine Point and Fort Smith, and was supported by the federal government. The commissioning of the Taltson Hydroelectric Development occurred in 1965 and the facility now supplies power to the communities of Fort Smith, Fort Resolution, Hay River, Enterprise and the Hay River Reserve. -

Lands Regional Contacts

LANDS REGIONAL CONTACTS Beaufort-Delta Region 86 Duck Lake Road ³ Bag Service #1 Inuvik, NT X0E 0T0 Telephone: 867-777-8900 Fax: 867-777-2090 E-mail: [email protected] Sahtu Region 31 Forrestry Drive Northern Cartrols Building Beaufort-Delta Box 126 Norman Wells, NT X0E 0V0 Telephone: 867-587-7200 Fax: 867-587-2928 E-mail: [email protected] Dehcho Region Regional Education Centre, 2nd Floor PO Box 150 Fort Simpson, NT X0E 0N0 Telephone: 867-695-2626 Ext. 202 Fax: 867-695-2615 e-mail: [email protected] Beaufort Sea North Slave Region Sachs Harbour 140 Bristol Avenue !( 16 Yellowknife Airport (mailing) Yellowknife, NT X1A 3T2 Telephone: 867-767-9187 Ext. 24185 Fax: 867-873-9754 E-mail: [email protected] South Slave Region Ulukhaktok !( 136 Simpson Street Tuktoyaktuk !( Evergreen Building Box 658 Fort Smith, NT X0E 0P0 Manager, Resource Management Telephone: 867-872-4343 Ext. 23 Aklavik Paulatuk !( Inuvik !( !( Donald Arey Fax: 867-872-3472 867-777-8906 E-mail: [email protected] Hay River Area Office Fort McPherson !( Tsiigehtchic Suite 203, 41 Capital Drive !( N.W Government of Canada Building .T. Yu kon Hay River, NT X0E 0R0 Telephone: 867-874-6995 Ext. 21 Fax: 867-874-2460 E-mail: [email protected] Colville Lake !( Fort Good Hope !( Manager, Resource Management Katherine Ades 867-587-7205 LEGEND LANDS Regional Boundaries M Great a c k Bear 0 20 40 80 120 e n z Sahtu Lake 1:2,100,000 KILOMETERS ie R iv DISCLAIMER !( e Norman Wells r THIS MAP IS FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY. -

Socio-Economic Assessment Toolbox (SEAT) Report for the Period 1 January to 31 December 2013 B SEAT REPORT 2013

Snap Lake Mine Socio-Economic Assessment Toolbox (SEAT) Report for the period 1 January to 31 December 2013 B SEAT REPORT 2013 CONTENTS Foreword . 1 Training in 2013 . 37 Executive Summary . 2 Opportunities for Students . 38 Introduction . 4 Scholarships and Summer Students . 38 Background . 4 NWT Post-secondary Scholarships Report Structure . 4 Awarded in 2013 . 39 Acknowledgements . 4 Shelby Skinner Puts Her Learning to Work at Snap Lake . 40 1 THE SEAT PROCESS 5 Keelan Mooney: De Beers Sponsorship . 41 Health and Wellness . 42 SEAT Objectives . 6 Fitness Centre . 42 Approach . 7 Fit for Purpose . 42 Stakeholder Engagement and the SEAT Process . 7 The Power of the Spoon . 43 Community Conversations . 8 Snap Lake Mine Family Visit . 44 NWT Business Policy . 45 2 SNAP LAKE MINE AND ITS COMMUNITIES OF INTEREST 11 Partnering with Northern Business . 45 Profile of Snap Lake Mine . 10 Partners in Business . 46 Employment . 12 Corporate Social Investment . 47 Mine Operations . 12 A Million Good Reasons to Invest . 47 Capital Investment . 12 Committed to Addressing the Social Life of Mine . 12 and Economic Impacts of the Mine . 48 Communities near Snap Lake . 13 Charity Golf Classic . 49 Tłįcho Communities . 14 Stanton Diamond Fundraiser . 49 Yellowknives Dene First Nations Communities . 22 Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation Community . 24 4 SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN 51 North Slave Métis Alliance . 26 Plan for Success . 52 Yellowknife . 26 A Million Good Reasons to Invest . 47 3 SOCIAL MANAGEMENT AND INVESTMENT 29 APPENDIX 1 - 2013 EMPLOYMENT DATA 57 Employment . 30 Employment by the Numbers . 30 APPENDIX 2 - GLOSSARY AND CONTACT DETAILS 69 Women in Mining . -

Great Slave 4 5111 4904 (5 5012 5102 4407 4914

4910 4909 4920 5010 4816 4903 4922 4601 4909 4912 4909 4919 4609 4702 4902 4904 4922 4919 5003 4909 4904 4922 5009 . 4911 4919 e 5013 4922 4701 v ve 4917 A A 4908 4903 4701 5010 4910 4915 5009 w 9 4922 5010 a 4 4701 5016 r 4912 4922 4 4301 4919 4709 6 D 4701 5013 5018 S l 4907 4919 4922 5003 4916 5015 5020 t. o 4807 o 4303 4909 4909 4921 4306 4807 5010 h 5009 5017 c 4810 4801 5012 5024 4305 4807 4913 4308 S 4908 4918 5009 5019 5004 5014 5024 4807 4920 4910 4915 5009 4501 4807 5016 5021 4310 4307 4807 4902 . 4919 5003 5006 4807 4912 5011 4 5023 ve 4807 4907 5006 5018 5102 5518 4807 4919 5013 7 A 4914 4902 5003 S 1 4309 ) 4909 4919 t 5 5104 4312 5518 4807 . 5012 5015 . 5003 5020 5106 5520 5519 ve 4911 5023 5103 4311 4914 4807 A 4910 5012 5022 5108 4314 9 5305 4807 4908 4915 4918 5009 4313 (4 5014 5023 5105 5110 4316 5527 4915 ive 5023 5107 r 4910 4315 D 4917 5016 5109 5112 4503 5522 l 4912 5004 5023 5525 a 5102 44 St 5210 i 4907 5018 511FALL4 2020. 5521 r 4909 4914 4919 5010 5020 5111 o 5016 m 5104 e 4909 5113 4401 M 4916 5001 5020 5103 5116 5018 5108 s 5001 5020 5524 n 4908 5019 5115 a 4913 5105 Electoral District of r 4913 5117 4403 te 5102 5004 e 5105 5110 4601 4402 4814 4910 5 ) 5021 5119 V 4912 2 4917 . -

Grants and Contributions Results Report 2015 – 2016

TABLED DOCUMENT 230-18(2) TABLED ON NOVEMBER 3, 2016 Grants and Contributions Results Report 2015 – 2016 November 2016 If you would like this information in another official language, call us. English Si vous voulez ces informations dans une autre langue officielle, contactez-nous. French Kīspin ki nitawihtīn ē nīhīyawihk ōma ācimōwin, tipwāsinān. Cree ch yat k . w n w , ts n . ch Ɂ ht s n n yat t a h ts k a y yat th at , n w ts n y t . Chipewyan n h h t hat k at h nah h n na ts ah . South Slavey K hsh t n k h ht y n w n . North Slavey ii wan ak i hii in k at at i hch hit yin hthan , iits t in hkh i. Gwich in Uvanittuaq ilitchurisukupku Inuvialuktun, ququaqluta. Inuvialuktun ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᑎᑎᕐᒃᑲᐃᑦ ᐱᔪᒪᒍᕕᒋᑦ ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᓕᕐᒃᓯᒪᓗᑎᒃ, ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐅᖄᓚᔪᓐᓇᖅᑐᑎᑦ. Inuktitut Hapkua titiqqat pijumagupkit Inuinnaqtun, uvaptinnut hivajarlutit. Inuinnaqtun Aboriginal Languages Secretariat: 867-767-9346 ext. 71037 Francophone Affairs Secretariat: 867-767-9343 TABLE OF CONTENTS MINISTER’S MESSAGE ....................................................................................................................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................................................................................2 Preface ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Official Voting Results 2007

2007 Election of the Sixteenth Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories Official Voting Results Published by the Chief Electoral Officer Office of the Chief Electoral Officer November 23, 2007 The Honourable Paul Delorey Speaker Legislative Assembly of the NWT P.O. Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Dear Mr. Speaker, Official Voting Results Pursuant to section 265 of the Elections and Plebiscites Act, it is my pleasure to provide you with the official voting results for the general election held on October 1, 2007 for the 16th Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories. This report provides poll-by-poll results for the 16 electoral districts in which an election was held and details the acclamations of candidates in three electoral districts. Sincerely, S. Arberry Chief Electoral Officer Mailing Address: #7, 4915 - 48th Street, Yellowknife, NT X1A 3S4 Phone: (867) 920-6999 or 1-800-661-0796 • Fax: (867) 873-0366 or 1-800-661-0872 e-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.electionsnwt.ca Table of Contents Official Voting Results Summary of Votes Cast by Electoral District .................................................................................................................. 1 Poll-by-Poll Results Deh Cho ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Frame Lake .................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Northwest Territories Liquor Licensing Board 65Th Annual Report

TD 531-18(3) TABLED ON AUGUST 22, 2019 Northwest Territories Liquor Licensing Board 65th Annual Report 2018 - 2019 201 June 27th, 9 Honourable Robert C. McLeod Minister Responsible for the NWT Liquor Licensing Board Dear Honourable Minister McLeod: In accordance with the Liquor Act, I am pleased to present the Northwest Territories Liquor Licensing Board’s 201 - 201 Annual Report. 8 9 Sincerely, Sandra Aitken Chairperson Contents Chairperson’s Message ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Board Overview ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Board Members and Staff .............................................................................................................................. 2 Board Activity ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Total Meetings ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Administration and Orientation Meetings .............................................................................................. 4 Licence Applications and Board Requests .............................................................................................. 4 Compliance Hearings ..................................................................................................................................... -

Environment and Natural Nt and Natural Resources

ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES Implementation Plan for the Action Plan for Boreal Woodland Caribou in the Northwest Territories: 2010-2015 The Action Plan for Boreal Woodland Caribou Conservation in the Northwest Territories was released after consulting with Management Authorities, Aboriginal organizations, communities, and interested stakeholders. This Implementation Plan is the next step of the Action Plan and will be used by Environment and Natural Resources to implement the actions in cooperation with the Tᰯch Government, Wildlife Management Boards and other stakeholders. In the future, annual status reports will be provided detailing the progress of the actions undertaken and implemented by Environment and Natural Resources. Implementation of these 21 actions will contribute to the national recovery effort for boreal woodland caribou under the federal Species at Risk Act . Implementation of certain actions will be coordinated with Alberta as part of our mutual obligations outlined in the signed Memorandum of Understanding for Cooperation on Managing Shared Boreal Populations of Woodland Caribou. This MOU acknowledges boreal caribou are a species at risk that are shared across jurisdictional lines and require co-operative management. J. Michael Miltenberger Minister Environment and Natural Resources IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Environment and Natural Resources Boreal Woodland Caribou Conservation in the Northwest Territories 2010–2015 July 2010 1 Headquarters Inuvik Sahtu North Slave Dehcho South Slave Action Initiative Involvement Region Region Region Region Region 1 Prepare and implement Co-lead the Dehcho Not currently Currently not Not currently To be developed To be developed comprehensive boreal caribou Boreal Caribou Working needed. needed. needed. by the Dehcho by the Dehcho range management plans in Group. -

Grants and Contributions

TABLED DOCUMENT 287-18(3) TABLED ON NOVEMBER 1, 2018 Grants and Contributions Results Report 2017 – 2018 Subventions et Contributions Le present document contient la traduction française du résumé et du message du ministre Rapport 2017 – 2018 October 2018 | Octobre 2018 If you would like this information in another official language, call us. English Si vous voulez ces informations dans une autre langue officielle, contactez-nous. French Kīspin ki nitawihtīn ē nīhīyawihk ōma ācimōwin, tipwāsinān. Cree Tłı̨chǫ yatı k’ę̀ę̀. Dı wegodı newǫ dè, gots’o gonede. Tłı̨chǫ Ɂerıhtł’ıś Dëne Sųłıné yatı t’a huts’elkër xa beyáyatı theɂą ɂat’e, nuwe ts’ën yółtı. Chipewyan Edı gondı dehgáh got’ı̨e zhatıé k’ę́ę́ edatł’éh enahddhę nıde naxets’ę́ edahłı.́ South Slavey K’áhshó got’ı̨ne xǝdǝ k’é hederı ɂedı̨htl’é yerınıwę nı ́dé dúle. North Slavey Jii gwandak izhii ginjìk vat’atr’ijąhch’uu zhit yinohthan jì’, diits’àt ginohkhìi. Gwich’in Uvanittuaq ilitchurisukupku Inuvialuktun, ququaqluta. Inuvialuktun ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᑎᑎᕐᒃᑲᐃᑦ ᐱᔪᒪᒍᕕᒋᑦ ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᓕᕐᒃᓯᒪᓗᑎᒃ, ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐅᖄᓚᔪᓐᓇᖅᑐᑎᑦ. Inuktitut Hapkua titiqqat pijumagupkit Inuinnaqtun, uvaptinnut hivajarlutit. Inuinnaqtun Indigenous Languages Secretariat: 867-767-9346 ext. 71037 Francophone Affairs Secretariat: 867-767-9343 TABLE OF CONTENTS MINISTER’S MESSAGE ............................................................. i MESSAGE DU MINISTRE .......................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................ 3 RÉSUMÉ ................................................................................. -

A Review of Information on Fish Stocks and Harvests in the South Slave Area, Northwest Territories

A Review of Information on Fish Stocks and Harvests in the South Slave Area, Northwest Territories DFO L b ary / MPO Bibliotheque 1 1 11 0801752111 1 1111 1 1 D.B. Stewart' Central and Arctic Region Department of Fisheries and Oceans Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6 'Arctic Biological Consultants Box 68, St. Norbert Postal Station 95 Turnbull Drive Winnipeg, MB, R3V 1L5. 1999 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2493 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Manuscript reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which deals with national or regional problems. Distribution is restricted to institutions or individuals located in particular regions of Canada. However, no restriction is placed on subject matter, and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Manuscript reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts and indexed in the Department's annual index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1-900 in this series were issued as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Biological Board of Canada, and subsequent to 1937 when the name of the Board was changed by Act of Parliament, as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 901-1425 were issued as Manuscript Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 1426-1550 were issued as Department of Fisheries and the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Manuscript Reports.