Tanta in the World and the World in Tanta 1856-1907

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transforming Community in the Italian Ecovillage Damanhur

Staying in the game From ‘intentional’ to ‘eco’: Transforming community in the Italian ecovillage Damanhur Amanda Jane Mallaghan From ‘intentional’ to ‘eco’: Transforming community in Damanhur Staying in the game From ‘intentional’ to ‘eco’: Transforming community in the Italian ecovillage Damanhur Amanda Jane Mallaghan 5579147 Utrecht University, 2016 Supervisor: NienKe Muurling Cover Photo: Celestrina 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1. Concepts of ‘community’ 8 1.1 The ecovillage movement; ‘renewing’ community 9 1.2 Play, Liminality and Communitas 11 Chapter 2. Being in ‘the between’ 13 2.1 Research settings and population 13 2.2 Methodology 15 2.3 Reflections on ‘the between’ 16 Chapter 3. Creating community 18 3.1 Structure 18 3.2 A ‘new’ society 23 Chapter 4. Connecting community 28 4.1Participation 29 4.2 Contribution 34 4.4 Solidarity 36 Chapter 5. Continuing community 39 5.1 Creating and connecting 39 5.2 Maintaining the balance 41 Bibliography 43 3 Acknowledgements It is here that I am to acKnowledge the various people that have helped me through this long journey. First I must thanK Damanhur, and all the people who allowed me into their world, who shared with me their stories. To Wapiti the coordinator of the new life program thanK you for organizing and planning, making sure we saw as much of Damanhur as we could. To the Porta della Luna family and the Dendera family, thank you for allowing me to stay in your homes and into your lives with such open arms. My time in Damanhur is an experience I wont forget, I am grateful to you all for that. -

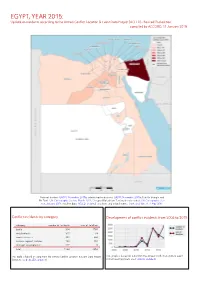

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Uber Launches Its First MENA-Wide Series of Events Called Ignite

Uber launches its first MENA-wide series of events called Ignite January 18, 2021 Uber announces the launch of Uber Ignite, its first series of events that brings together the diverse perspectives of thought leaders, regulators, corporates, start-ups and innovators to collectively address a number of urban challenges faced in the MENA region. The series aims to equip guests with the knowledge needed to unlock and maximize technology-focused opportunities for growth in our communities. Abdellatif Waked, General Manager of Uber Middle East and Africa, commented on the launch: “I’m excited for Ignite to launch in the MENA region as a platform for dialogue and engagement to address current urban challenges. As our region continues to modernise and develop at an increasing rate, we believe we can play a key role in bringing together experts from across multiple sectors and industries to collectively address issues and provide recommendations.” Titled as ‘Tech for Transport Safety’, Uber Ignite's inaugural panel discussion will be held on January 26, and will focus on how safety across multiple modes of transport is evolving, and the role of technology in meeting the current mobility demands in urban development. Representatives from Virgin Hyperloop, Derq, Trella, General Motors, and Uber will bring their expertise to the discussion to shine light on potential solutions that be conceptualised and developed across the region. The event will be hosted virtually due to Covid-19 for the safety of all participants and attendees. About Uber: Uber’s mission is to bring reliable transportation to everywhere, for everyone. We started in 2010 to solve a simple problem: how do you get a ride at the touch of a button? Seven years and more than two billion trips later, we have started tackling an even greater challenge: reducing congestion and pollution in our cities by getting more people into fewer cars. -

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development By Dr. Hamed Korkor Chairman Assistant Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EGAS United Nations – Economic Commission for Europe Working Party on Gas 17th annual Meeting Geneva, Switzerland January 23-24, 2007 Egyptian Natural Gas Industry History EarlyEarly GasGas Discoveries:Discoveries: 19671967 FirstFirst GasGas Production:Production:19751975 NaturalNatural GasGas ShareShare ofof HydrocarbonsHydrocarbons EnergyEnergy ProductionProduction (2005/2006)(2005/2006) Natural Gas Oil 54% 46 % Total = 71 Million Tons 26°00E 28°00E30°00E 32°00E 34°00E MEDITERRANEAN N.E. MED DEEPWATER SEA SHELL W. MEDITERRANEAN WDDM EDDM . BG IEOC 32°00N bp BALTIM N BALTIM NE BALTIM E MED GAS N.ALEX SETHDENISE SET -PLIOI ROSETTA RAS ELBARR TUNA N BARDAWIL . bp IEOC bp BALTIM E BG MED GAS P. FOUAD N.ABU QIR N.IDKU NW HA'PY KAROUS MATRUH GEOGE BALTIM S DEMIATTA PETROBEL RAS EL HEKMA A /QIR/A QIR W MED GAS SHELL TEMSAH ON/OFFSHORE SHELL MANZALAPETROTTEMSAH APACHE EGPC EL WASTANI TAO ABU MADI W CENTURION NIDOCO RESTRICTED SHELL RASKANAYES KAMOSE AREA APACHE Restricted EL QARAA UMBARKA OBAIYED WEST MEDITERRANEAN Area NIDOCO KHALDA BAPETCO APACHE ALEXANDRIA N.ALEX ABU MADI MATRUH EL bp EGPC APACHE bp QANTARA KHEPRI/SETHOS TAREK HAMRA SIDI IEOC KHALDA KRIER ELQANTARA KHALDA KHALDA W.MED ELQANTARA KHALDA APACHE EL MANSOURA N. ALAMEINAKIK MERLON MELIHA NALPETCO KHALDA OFFSET AGIBA APACHE KALABSHA KHALDA/ KHALDA WEST / SALLAM CAIRO KHALDA KHALDA GIZA 0 100 km Up Stream Activities (Agreements) APACHE / KHALDA CENTURION IEOC / PETROBEL -

Egyptian National Action Program to Combat Desertification

Arab Republic of Egypt UNCCD Desert Research Center Ministry of Agriculture & Land Reclamation Egyptian National Action Program To Combat Desertification June, 2005 UNCCD Egypt Office: Mail Address: 1 Mathaf El Mataria – P.O.Box: 11753 El Mataria, Cairo, Egypt Tel: (+202) 6332352 Fax: (+202) 6332352 e-mail : [email protected] Prof. Dr. Abdel Moneim Hegazi +202 0123701410 Dr. Ahmed Abdel Ati Ahmed +202 0105146438 ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation Desert Research Center (DRC) Egyptian National Action Program To Combat Desertification Editorial Board Dr. A.M.Hegazi Dr. M.Y.Afifi Dr. M.A.EL Shorbagy Dr. A.A. Elwan Dr. S. El- Demerdashe June, 2005 Contents Subject Page Introduction ………………………………………………………………….. 1 PART I 1- Physiographic Setting …………………………………………………….. 4 1.1. Location ……………………………………………………………. 4 1.2. Climate ……...………………………………………….................... 5 1.2.1. Climatic regions…………………………………….................... 5 1.2.2. Basic climatic elements …………………………….................... 5 1.2.3. Agro-ecological zones………………………………………….. 7 1.3. Water resources ……………………………………………………... 9 1.4. Soil resources ……...……………………………………………….. 11 1.5. Flora , natural vegetation and rangeland resources…………………. 14 1.6 Wildlife ……………………………………………………………... 28 1.7. Aquatic wealth ……………………………………………………... 30 1.8. Renewable energy ………………………………………………….. 30 1.8. Human resources ……………………………………………………. 32 2.2. Agriculture ……………………………………………………………… 34 2.1. Land use pattern …………………………………………………….. 34 2.2. Agriculture production ………...……………………………………. 34 2.3. Livestock, Poultry and Fishing production …………………………. 39 2.3.1. Livestock production …………………………………………… 39 2.3.2. Poultry production ……………………………………………… 40 2.3.3. Fish production………………………………………………….. 41 PART II 3. Causes, Processes and Impact of Desertification…………………………. 43 3.1. Causes of desertification ……………………………………………….. 43 Subject Page 3.2. Desertification processes ………………………………………………… 44 3.2.1. Urbanization ……………………………………………………….. 44 3.2.2. Salinization…………………………………………………………. -

Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works

Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works Sector - Q4 2018 Report Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works 4 (2018) Report American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt - Business Information Center 1 of 15 Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works Sector - Q4 2018 Report Special Remarks The Water & Waste-Water Equipment & Works Q4 2018 report provides a comprehensive overview of the Water & List of sub-sectors Waste-Water Equipment & Works sector with focus on top tenders, big projects and important news. Irrigation & Drainage Canals Irrigation & Drainage Networks Tenders Section Irrigation & Drainage Pumping Stations Potable Water & Waste-Water Pipelines - Integrated Jobs (Having a certain engineering component) - sorted by Potable Water & Waste-Water Pumps - Generating Sector (the sector of the client who issued the tender and who would pay for the goods & services ordered) Water Desalination Stations - Client Water Wells Drilling - Supply Jobs - Generating Sector - Client Non-Tenders Section - Business News - Projects Awards - Projects in Pre-Tendering Phase - Privatization and Investments - Published Co. Performance - Loans & Grants - Fairs and Exhibitions This report includes tenders with bid bond greater than L.E. 10,000 and valuable tenders without bid bond Tenders may be posted under more than one sub-sector Copyright Notice Copyright ©2018, American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt (AmCham). All rights reserved. Neither the content of the Tenders Alert Service (TAS) nor any part of it may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt. In no event shall AmCham be liable for any special, indirect or consequential damages or any damages whatsoever resulting from loss of use, data or profits. -

The Rosetta Stone

THE J ROSETTA STONE PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM. London : SOLD AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM f922. Price Sixpence. [all rights reserved.] I \ V'.'. EXCHANGE PHOTO ET IMP. DONALD :• : . » MACBETH, LONDON THE ROSETTA STONE. r % * THE DISCOVERY OF THE STONE. famous slab of black basalt which stands at the southern end of the Egyptian Gallery in the British Museum, and which has for more than a century " THEbeen universally known as the Rosetta Stone," was found at a spot near the mouth of the great arm of the Nile that flows through the Western Delta " " to the sea, not far from the town of Rashid," or as Europeans call it, Rosetta." According to one account it was found lying on the ground, and according to another it was built into a very old wall, which a company of French soldiers had been ordered to remove in order to make way for the foundations of an addition to the fort, " ' afterwards known as Fort St. Julien. '* The actual finder of the Stone was a French Officer of Engineers, whose name is sometimes spelt Boussard, and sometimes Bouchard, who subsequently rose to the rank of General, and was alive in 1814. He made his great discovery in August, 1799. Finding that there were on one side of the Stone lines of strange characters, which it was thought might be writing, as well as long lines of Greek letters, Boussard reported his discovery to General Menou, who ordered him to bring the Stone to his house in Alexandria. This was immediately done, and the Stone was, for about two years, regarded as the General's private property. -

Flora and Vegetation of Wadi El-Natrun Depression, Egypt

PHYTOLOGIA BALCANICA 21 (3): 351 – 366, Sofia, 2015 351 Habitat diversity and floristic analysis of Wadi El-Natrun Depression, Western Desert, Egypt Monier M. Abd El-Ghani, Rim S. Hamdy & Azza B. Hamed Department of Botany and Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt; email: [email protected] (corresponding author) Received: May 18, 2015 ▷ Accepted: October 15, 2015 Abstract. Despite the actual desertification in Wadi El-Natrun Depression nitrated by tourism and overuse by nomads, 142 species were recorded. Sixty-one species were considered as new additions, unrecorded before in four main habitats: (1) croplands (irrigated field plots); (2) orchards; (3) wastelands (moist land and abandoned salinized field plots); and (4) lakes (salinized water bodies). The floristic analysis suggested a close floristic relationship between Wadi El-Natrun and other oases or depressions of the Western Desert of Egypt. Key words: biodiversity, croplands, human impacts, lakes, oases, orchards, wastelands Introduction as drip, sprinkle and pivot) are used in the newly re- claimed areas, the older ones follow the inundation Wadi El-Natrun is part of the Western (Libyan) Desert type of irrigation (Soliman 1996; Abd El-Ghani & El- adjacent to the Nile Delta (23 m below sea level), lo- Sawaf 2004). Thus the presence of irrigation water as cated approximately 90 km southwards of Alexandria underground water of suitable quality, existence of and 110 km NW of Cairo. It is oriented in a NW–SE natural fresh water springs and availability of water direction, between longitudes 30°05'–30°36'E and lat- contained in the sandy layers above the shallow wa- itudes 30°29'–30°17'N (King & al. -

UNHCR Operation

Update no 16 Humanitarian Situation in Libya and the Neighbouring Countries 4 April 2011 Highlights • The Humanitarian Coordinator for Libya visited Ras Djir at the Tunisian-Libyan border on 2 April. In a meeting with the humanitarian agencies in Choucha camp he raised concerns about several issues, including 1) the lack of reliable information from inside Libya, 2) the disruption of the health care system in Libya due to the massive flight of non-Libyan nurses and medical workers, and 3) the likelihood of a continuous steady flow of mixed migration out of Libya. • An increased influx of Libyan families crossing into Egypt was observed by UNHCR staff at Saloum border. In the past days, up to 2,500 Libyans per day crossed into Egypt. • On 31 March, the High Commissioner finalized his mission to Egypt together with UNHCR’s Director for the Middle East and North Africa. In his meeting with the Egyptian Prime Minister the HC thanked Egypt for keeping its borders open to all those fleeing Libya at a time when Egypt is dealing with its own complex changes. • An increasing number of wounded Libyans have been reported at border crossings in addition to UNHCR staff distributing plastic sheets to new arrivals from several boat loads arriving with family members in Chad. / UNHCR /N.Bose Tunisia. Population movements By 3 April, a total of 439,561 persons crossed from Libya to neighbouring countries. There continues to be a steady influx of third country nationals both to Tunisia and Egypt. Tunisia Egypt Niger Algeria** Sudan*** Chad Tunisians 19,841 Egyptians 81,412 Nigeriens 25,422 not available not available not available Libyans* 36,605 Libyans* 43,086 Others 1,825 Others 161,317 Others 49,551 TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL 217,763 TOTAL 174,049 TOTAL 27,247 10,679 2,800 TOTAL 4,719 Source: IOM in cooperation with national authorities * Includes usual border crossings of commuters, traders etc. -

The Ohio State University

MAKING COMMON CAUSE?: WESTERN AND MIDDLE EASTERN FEMINISTS IN THE INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MOVEMENT, 1911-1948 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charlotte E. Weber, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Leila J. Rupp, Adviser Professor Susan M. Hartmann _________________________ Adviser Professor Ellen Fleischmann Department of History ABSTRACT This dissertation exposes important junctures between feminism, imperialism, and orientalism by investigating the encounter between Western and Middle Eastern feminists in the first-wave international women’s movement. I focus primarily on the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship, and to a lesser extent, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. By examining the interaction and exchanges among Western and Middle Eastern women (at conferences and through international visits, newsletters and other correspondence), as well as their representations of “East” and “West,” this study reveals the conditions of and constraints on the potential for feminist solidarity across national, cultural, and religious boundaries. In addition to challenging the notion that feminism in the Middle East was “imposed” from outside, it also complicates conventional wisdom about the failure of the first-wave international women’s movement to accommodate difference. Influenced by growing ethos of cultural internationalism -

Ideas Concerning the Historical Identity and the Connections of the City of Phaselis an Eastern Mediterranean Port*

Mediterranean Journal of Humanities mjh.akdeniz.edu.tr II/1, 2012, 205-212 Ideas Concerning the Historical Identity and the Connections of the City of Phaselis an Eastern Mediterranean Port* Bir Doğu Akdeniz Limanı Olarak Phaselis Kentinin Tarihsel Kimliği ve Bağlantıları Hakkında Düşünceler Nihal TÜNER ÖNEN** Abstract: This article is based upon ancient sources and numismatic and epigraphic evidence and evaluates the historical identity of Phaselis, located on the border of Lycia-Pamphylia, within the framework of its relations with eastern Mediterranean ports. Phaselis and settlements such as: Gagai, Corydalla and Rho- diapolis had a Hellenic identity in early times and this is compatible with Rhodes’ attempts especially in the VII c. to found new colonies in Lycia and Cilicia, reflecting its desire to participate in the ongoing commercial activities in the eastern Mediterranean. When the temporal context of this dominance is investigated, antroponymic data interestingly reveals that Phaselis retained its Hellenic characters until the Roman Period, while other Rhodian colonies on the east Lycian coast lost many elements of their Hellenic identity in the V and IV centuries B.C. The second section deals with the inferences drawn concerning the historical identity of the city in the perspective of its connections within the eastern Mediterranean. This section examines the commercial aspects of this relationship in particular through presenting the spread of Archaic Period coins struck by Phaselis in eastern Mediterranean cities such as: Damanhur, Benha el Asl, Zagazig, in Syria, in the Anti-Lebanon and in Jordan. Thus, through extending the observations of these commercial links within the context of emporion the city possessed in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods, data concerning the network of regional and inter-regional relations formed by Phaselis in the eastern Mediterranean are examined in detail. -

Arab African International Bank (AAIB) Maintained Its Leading Our Ability to Confront Future Challenges and Growth Position As a Leading Financial Institution

“50 GOLDEN YEARS OF VALUE CREATION” VISI N To be the leading financial group in Egypt providing innovative services with a strong regional presence being the gateway for international business into the region. Cover: The Royal Geographical | Society Qasr El Aini Street | Photographer: Barry Iverson This image: The Royal Geographical Society | Qasr El Aini Street | Photographer: Shahir Sirry “ 50 GOLDEN YEARS OF CONFIDENCE” been at the core of AAIB’s values, guiding all its interactions with its clients and a mission to do what is right. TABLE F C NTENT Shareholders 4 Board of Directors 5 Chairman’s Statement 6 Vice Chairman & Managing Director’s Report 8 Financial Statements 13 Balance sheet 14 Income statement 14 Statement of changes in owners’ equity 15 Statement of cash flows 15 Statement of proposed appropriation 16 Notes to the financial statements 16 Auditors’ Report 50 Branches 52 Location description Door of “Inal Al Yusufi” Mosque | Khayameya | Islamic Cairo | Photographer: Karim El Hayawan “ GOLDEN YEARS OF 50 STRENGTH” Only when a solid foundation is built, can an entity really prosper. The trust we have in the Central Bank of Egypt, the Kuwait Investment Authority as shareholders and the stability having a strong dollar based equity gives us the SHARH LDERS PERCENTAGE OF HOLDING Central Bank of Egypt, Egypt 49.37% Kuwait Investment Authority, Kuwait 49.37% Others 1.26% Others 1.26% Kuwait Investment Authority, Central Bank Kuwait of Egypt, 49.37% Egypt 49.37% The Royal Geographical | Society Qasr El Aini Street | Photographer: Barry Iverson “ GOLDEN YEARS OF 50 PASSION ” Our passion is what fuels our growth.