Low Molecular Weight Heparins and Heparinoids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHO Drug Information Vol. 12, No. 3, 1998

WHO DRUG INFORMATION VOLUME 12 NUMBER 3 • 1998 RECOMMENDED INN LIST 40 INTERNATIONAL NONPROPRIETARY NAMES FOR PHARMACEUTICAL SUBSTANCES WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION • GENEVA Volume 12, Number 3, 1998 World Health Organization, Geneva WHO Drug Information Contents Seratrodast and hepatic dysfunction 146 Meloxicam safety similar to other NSAIDs 147 Proxibarbal withdrawn from the market 147 General Policy Issues Cholestin an unapproved drug 147 Vigabatrin and visual defects 147 Starting materials for pharmaceutical products: safety concerns 129 Glycerol contaminated with diethylene glycol 129 ATC/DDD Classification (final) 148 Pharmaceutical excipients: certificates of analysis and vendor qualification 130 ATC/DDD Classification Quality assurance and supply of starting (temporary) 150 materials 132 Implementation of vendor certification 134 Control and safe trade in starting materials Essential Drugs for pharmaceuticals: recommendations 134 WHO Model Formulary: Immunosuppressives, antineoplastics and drugs used in palliative care Reports on Individual Drugs Immunosuppresive drugs 153 Tamoxifen in the prevention and treatment Azathioprine 153 of breast cancer 136 Ciclosporin 154 Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and Cytotoxic drugs 154 withdrawal reactions 136 Asparaginase 157 Triclabendazole and fascioliasis 138 Bleomycin 157 Calcium folinate 157 Chlormethine 158 Current Topics Cisplatin 158 Reverse transcriptase activity in vaccines 140 Cyclophosphamide 158 Consumer protection and herbal remedies 141 Cytarabine 159 Indiscriminate antibiotic -

Treatment of 51 Pregnancies with Danaparoid Because of Heparin

©2005 Schattauer GmbH,Stuttgart Blood Coagulation, Fibrinolysis and CellularHaemostasis Treatment of 51 pregnancies withdanaparoidbecause of heparin intolerance EdelgardLindhoff-Last1 ,Hans-Joachim Kreutzenbeck2 ,Harry N. Magnani3 1 Division ofVascular Medicine,Department of Internal Medicine,University Hospital Frankfurt, Germany 2 MedicalDepartment, Celltech, Essen, Germany 3 Clinical Consultant Marketing, OrganonBV, Oss,The Netherlands Summary Pregnant patients withacute venous thrombosis or ahistoryof required (3/14) or an adverse eventled to atreatment discon- thrombosis mayneed alternative anticoagulation, when heparin tinuation (11/14).Four maternal bleeding events were recorded intolerance occurs. Onlylimited dataonthe useofthe hepari- during pregnancy, deliveryorpostpartum, twoofthemwere noiddanaparoid areavailable in literature.We reviewedthe use fatal duetoplacental problems.Three fetal deathswererec- of danaparoid in 51 pregnancies of 49 patients identified in litera- orded,all associated with maternal complications antedating da- turebetween 1981 and 2004.All patients had developed hepa- naparoiduse.Danaparoid cross-reactivity was suspectedin4 rin intolerance (32 duetoheparin-induced thrombocytopenia, HITpatientsand 5non-HITpatientswith skin reactions and was 19 mainlydue to heparin-induced skin rashes)and had acurrent confirmedserologicallyinone of the twoHIT patients tested.In and/or pasthistoryofthromboembolic complications.The initial none of fivefetal cordblood- andthree maternal breast milk- danaparoid doseregimens ranged -

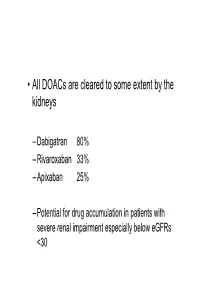

• All Doacs Are Cleared to Some Extent by the Kidneys

• All DOACs are cleared to some extent by the kidneys – Dabigatran 80% – Rivaroxaban 33% – Apixaban 25% – Potential for drug accumulation in patients with severe renal impairment especially below eGFRs <30 Warfarin is unaffected by renal impairment (only • Rivaroxaban & Apixaban are both oral direct inhibitor of factor Xa. • Rivaroxaban doses recommended for clinical use are 15mg od and 20 mg od (15 mg bd for first 3 weeks of treatment of DVT). • Apixaban 5mg bd or 2.5mg bd • Rivaroxaban peak plasma levels are reached 2 to 3 h after ingestion • Apixaban peak plasma levels are reached ~3hrs after ingestion • Rivaroxaban is taken with food – Apixaban without food • Rivaroxaban is 33% renaly excreted and has a half-life of 9 h in patients with normal renal function. – There is an analogy with Therapeutic LMWH – We very rarely ask for an anti-Xa assay • And what is the clinical significance of a Xa assay ? (Cut off values are largely arbitrary) – Fixed doses – Importance of When the last dose was taken ? – Importance of What is the renal function ? – If bleeding • What is the nature of the bleeding ? • In extremis we can give protamine sulphate (? Efficacy) • How to manage bleeding on a DOAC? –How severe is the bleeding ? –When was the last dose of medication ? –What is the renal function ? – Recheck –If minor bleeding; epistaxis, gingival, bruising, menorrhagia • Withhold the NOAC (when was the last dose taken?) • Recheck renal function • Check FBC • Local measures • Unlikely to require further intervention – Re-challenge – ? Switch NOAC -

Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia (Hit)

HEPARIN‐INDUCED THROMBOCYTOPENIA (HIT) OBJECTIVE: To assist clinicians with the diagnosis and initial management of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and suspected HIT. BACKGROUND: HIT is a transient, immune‐mediated adverse drug reaction in patients recently exposed to heparin that generally produces thrombocytopenia and often results in venous and/or arterial thrombosis. HIT occurs in up to 5% of patients receiving unfractionated heparin (UFH) and in <1% who receive low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). HIT is characterised by immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies that recognize an antigen complex of platelet factor 4 (PF4) bound to heparin. These antibodies trigger a highly prothrombotic state by causing intravascular platelet aggregation, intense platelet, monocyte and endothelial cell activation and excessive thrombin generation. CLINICAL FEATURES: HIT typically presents with a fall in platelet count with or without venous and/or arterial thrombosis. Thrombocytopenia: A platelet count fall >30% beginning 5‐10 days after heparin exposure, in the absence of other causes of thrombocytopenia, should be considered to be HIT, unless proven otherwise. A more rapid onset of platelet count fall (often within 24 hours of heparin exposure) can occur when there is a history of heparin exposure within the preceding 3 months. Bleeding is very infrequent. Thrombosis: HIT is associated with a high risk (30‐50%) of new venous or arterial thromboembolism. Thrombosis may be the presenting clinical manifestation of HIT or can occur during or shortly after the thrombocytopenia. Other clinical manifestations of HIT: Less frequent manifestations include heparin‐induced skin lesions, adrenal hemorrhagic infarction, transient global amnesia, and acute systemic reactions (e.g. chills, dyspnea, cardiac or respiratory arrest following IV heparin bolus). -

Anticoagulation Reversal Guideline for Adults

Anticoagulation Reversal Guideline for Adults Antithrombotic reversal strategies should be limited to clinical situations (i.e. life-threatening bleeding) where the immediate need for anticoagulant reversal outweighs the risk of thrombosis (either from the reversal agent itself or normalization of coagulation in a patient with underlying thromboembolic risk). These recommendations are meant to serve as general guidelines and should not replace clinical judgment. Always seek input from the appropriate specialists when indicated and include the patient and/or family in shared decision making when possible. This document is not meant to guide selection of patients for reversal therapies. Please refer to appropriate national guidelines to aide decision- making regarding need for reversal, if warranted. 1. ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Management of Bleeding in Patients on Oral Anticoagulants 2. Guideline for Reversal of Antithrombotics in Intracranial Hemorrhage: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and Society of Critical Care Medicine All indications for anticoagulation are considered, including atrial fibrillation, venous thromboembolism, prosthetic cardiac valves, and intracardiac thrombus. Mechanical circulatory support devices, including temporary or permanent ventricular assist devices (i.e. LVADs), are excluded from this document. Whenever possible, anticoagulation should be resumed in a timely manner to avoid thromboembolic complications related to the underlying indication for anticoagulation. This guideline does not provide recommendations on resuming anticoagulation. References: • Tomaselli GF, Mahaffey KW, Cuker A, et al. 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Management of Bleeding in Patients on Oral Anticoagulants: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Experts Consensus Decisions Pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol. -

For the Use Only of Registered Medical Practitioner Or a Hospital Or a Laboratory

For the use only of Registered Medical Practitioner or a Hospital or a Laboratory FRAXIPARINE® Nadroparin Calcium Injection QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION FRAXIPARINE® [Nadroparin calcium solution for injection (9,500 IU AXa /ml)] Pre-filled syringes: - Each pre-filled (0.2 ml) syringe contains: Nadroparin Calcium BP 1,900 IU AXa. - Each pre-filled (0.3 ml) syringe contains: Nadroparin Calcium BP 2,850 IU AXa. - Each pre-filled (0.4 ml) syringe contains: Nadroparin Calcium BP 3,800 IU AXa. Graduated pre-filled syringes: - Each pre-filled (0.6 ml) syringe contains: Nadroparin Calcium BP to 5,700 IU AXa. - Each pre-filled (0.8 ml) syringe contains: Nadroparin Calcium BP to 7,600 IU AXa. - Each pre-filled (1 ml) syringe contains: Nadroparin Calcium BP to 9,500 IU AXa. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Solution for injection. CLINICAL PARTICULARS Therapeutic Indications The prophylaxis of thromboembolic disorders, such as: - those associated with general or orthopedic surgery - those in high risk medical patients (respiratory failure and/or respiratory infection and/or cardiac failure), hospitalised in intensive care unit. The treatment of thromboembolic disorders. The prevention of clotting during haemodialysis. The treatment of unstable angina and non-Q wave myocardial infarction. Posology and Method of Administration Particular attention should be paid to the specific dosing instructions for each proprietary Low Molecular Weight Heparin, as different units of measurement (units or mg) are used to 1 express doses. Nadroparin should therefore not be used interchangeably with other low molecular weight heparins during ongoing treatment. In addition, care should be taken to use the correct formulation of nadroparin, either single or double strength, as this will affect the dosing regimen. -

Perioperative Management of Patients Treated with Antithrombotics in Oral Surgery

SFCO/Perioperative management of patients treated with antithrombotic agents in oral surgery/Rationale/July 2015 SOCIÉTÉ FRANÇAISE DE CHIRURGIE ORALE [FRENCH SOCIETY OF ORAL SURGERY] IN COLLABORATION WITH THE SOCIÉTÉ FRANÇAISE DE CARDIOLOGIE [FRENCH SOCIETY OF CARDIOLOGY] AND THE PERIOPERATIVE HEMOSTASIS INTEREST GROUP Space Perioperative management of patients treated with antithrombotics in oral surgery. RATIONALE July 2015 P a g e 1 | 107 SFCO/Perioperative management of patients treated with antithrombotic agents in oral surgery/Rationale/July 2015 Abbreviations ACS Acute coronary syndrome(s) ADP Adenosine diphosphate Afib Atrial Fibrillation AHT Arterial hypertension Anaes Agence nationale d’accréditation et d’évaluation en santé [National Agency for Accreditation and Health Care Evaluation] APA Antiplatelet agent(s) aPTT Activated partial thromboplastin time ASA Aspirin BDMP Blood derived medicinal products BMI Body mass index BT Bleeding Time cAMP Cyclic adenosine monophosphate COX-1 Cyclooxygenase 1 CVA Cerebral vascular accident DIC Disseminated intravascular coagulation DOA Direct oral anticoagulant(s) DVT Deep vein thrombosis GEHT Study Group on Hemostasis and Thrombosis (groupe d’étude sur l’hémostase et la thrombose) GIHP Hemostasis and Thrombosis Interest Group (groupe d’intérêt sur l’hémostase et la thrombose) HAS Haute autorité de santé [French Authority for Health] HIT Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia IANB Inferior alveolar nerve block INR International normalized ratio IV Intravenous LMWH Low-molecular-weight heparin(s) -

The Treatment and Prevention Ofacute Ischemic Stroke

EDITORIAL Alvaro Nagib Atallah* The treatment and prevention of acute ischemic stroke rotecting the brain from the consequences .of alternated with placebo (lower dose) and placebo injections vascular obstruction is obviously very important. every 12 hours, for 10 days. The evaluation at 6 months PHowever, how to manage this is a very complex showed that the treated group had a lower incidence rate task. Three recent studies have provided evidence that of poor outcomes, death or dependency in daily activities, I 3 should not be ignored or misinterpreted by physicians. - 45 vs. 65%. In other words, it was necessary to treat 5 The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and patients to benefit one. Evaluations at 10 days did not show Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Groupl shows the results of a differences in death rates or haemorrhage transformation randomized, collaborative placebo-controlled trial. Six of the cerebral infarction. hundred and twenty-four patients were studied. The The Multicentre Acute Stroke Trial-Italy (MAST-I) treatment was started before 90' of the start of the stroke Group compared the effectiveness of streptokinase, aspirin or before 180'. Patients received recombinant rt-PA and a combination of both for the treatment of ischemic (alteplase) 0.9 mg/kg or placebo. A careful neurological stroke. Six hundred and twenty-two patients were evaluation was done at 24 hours and 3 months after the randomized to receive I hour infusions of 1.5 mD of stroke. streptokinase alone, the same dose of streptokinase plus There were no significant differences between the 300 mg of buffered aspirin, or 300 mg of aspirin alone for groups at 24 hours after the stroke. -

Low Molecular Weight Heparinoid, ORG 10172 (Danaparoid), and Outcome After Acute Ischemic Stroke a Randomized Controlled Trial

Original Contributions Low Molecular Weight Heparinoid, ORG 10172 (Danaparoid), and Outcome After Acute Ischemic Stroke A Randomized Controlled Trial The Publications Committee for the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) Investigators Context.—Anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin is used commonly for ANTICOAGULATION with unfrac- treatment of acute ischemic stroke, but its use remains controversial because it has tionated heparin commonly is used to not been shown to be effective or safe. Low molecular weight heparins and hepa- treat persons with acute ischemic 1 rinoids have been shown to be effective in preventing deep vein thrombosis in per- stroke. However, the use of heparin re- mains controversial because it is not es- sons with stroke, and they might be effective in reducing unfavorable outcomes fol- 2-6 lowing ischemic stroke. tablished as safe or effective. A recent open trial demonstrated a modest effect Objective.—To test whether an intravenously administered low molecular from subcutaneously administered hep- weight heparinoid, ORG 10172 (danaparoid sodium), increases the likelihood of a arin in preventing recurrent stroke favorable outcome at 3 months after acute ischemic stroke. within 14 days but no improvement in Design.—Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. outcomes.7 Thus, whether an intrave- Setting and Participants.—Between December 22, 1990, and December 6, nously administered anticoagulant that 1997, 1281 persons with acute stroke were enrolled at 36 centers across the United would act more rapidly would be effec- States. tiveremainsunanswered.Thesearchfor Intervention.—A 7-day course of ORG 10172 or placebo was given initially as alternative medications that possess the a bolus within 24 hours of stroke, followed by continuous infusion in addition to the antithrombotic characteristics of hepa- best medical care. -

Predicting Potential Drugs for Breast Cancer Based on Mirna and Tissue Specificity

Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, Vol. 14 971 Ivyspring International Publisher International Journal of Biological Sciences 2018; 14(8): 971-982. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.23350 Research Paper Predicting Potential Drugs for Breast Cancer based on miRNA and Tissue Specificity Liang Yu, Jin Zhao and Lin Gao School of Computer Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi'an, 710071, P.R. China. Corresponding author: [email protected] © Ivyspring International Publisher. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). See http://ivyspring.com/terms for full terms and conditions. Received: 2017.10.16; Accepted: 2017.12.14; Published: 2018.05.22 Abstract Network-based computational method, with the emphasis on biomolecular interactions and biological data integration, has succeeded in drug development and created new directions, such as drug repositioning and drug combination. Drug repositioning, that is finding new uses for existing drugs to treat more patients, offers time, cost and efficiency benefits in drug development, especially when in silico techniques are used. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) play important roles in multiple biological processes and have attracted much scientific attention recently. Moreover, cumulative studies demonstrate that the mature miRNAs as well as their precursors can be targeted by small molecular drugs. At the same time, human diseases result from the disordered interplay of tissue- and cell lineage-specific processes. However, few computational researches predict drug-disease potential relationships based on miRNA data and tissue specificity. Therefore, based on miRNA data and the tissue specificity of diseases, we propose a new method named as miTS to predict the potential treatments for diseases. -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 1/41

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 ATC code ATC group / Active substance (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit DDD/1000/ day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 167,8985 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0738 A01AB09 Miconazole (O) 7088 g 0,2 g 0,0738 A01AB12 Hexetidine (O) 1951200 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+ Benzocaine (dental) 30200 pieces A01AB82 Demeclocycline+ Triamcinolone (dental) 680 g A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+ Thymol (dental) 3094 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+ Cetylpyridinium chloride (gingival) 227150 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+ Cetrimide (O) 30900 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate (O) 864720 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+ Chamomille extract (O) 370080 g A01AD90 Lidocaine+ Paraformaldehyde (dental) 405 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 47,1312 A02A ANTACIDS 1,0133 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 1,0133 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 811120 pieces 10 pieces 0,1689 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 3101974 ml 50 ml 0,1292 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+ Magnesium carbonate (O) 3434232 pieces 10 pieces 0,7152 DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 46,1179 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 2,3855 A02BA02 Ranitidine (O) 340327,5 g 0,3 g 2,3624 A02BA02 Ranitidine (P) 3318,25 g 0,3 g 0,0230 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 43,7324 A02BC01 Omeprazole -

ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) Reperfusion Order Set

Form Title ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) Reperfusion Order Set Form Number CH-0454 © 2018, Alberta Health Services, CKCM This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The license does not apply to content for which the Alberta Health Services is not the copyright owner. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Disclaimer: This material is intended for use by clinicians only and is provided on an DVLVZKHUHLVEDVLV$OWKRXJKUHDVRQDEOHHIIRUWVZHUHPDGHWRFRQ¿UPWKHDFFXUDF\RIWKH information, Alberta Health Services does not make any representation or warranty, express, LPSOLHGRUVWDWXWRU\DVWRWKHDFFXUDF\UHOLDELOLW\FRPSOHWHQHVVDSSOLFDELOLW\RU¿WQHVVIRU a particular purpose of such information. This material is not a substitute for the advice of a TXDOL¿HGKHDOWKSURIHVVLRQDO$OEHUWD+HDOWK6HUYLFHVH[SUHVVO\GLVFODLPVDOOOLDELOLW\IRUWKHXVH of these materials, and for any claims, actions, demands or suits arising from such use. Patient label placed here (if applicable) or if labels are not + used, minimum information below is required + Last Name First Name Birthdate (yyyy-Mon-dd) Gender PHN # ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) Reperfusion Order Set Phone Number Date Time Initial (yyyy-Mon-dd) (hh:mm) 1. Patient Treatment & Monitoring Complete 12 lead ECG Stat if not already completed. Review with Physician. Take initial vital signs (Temp, HR, RR, SpO2, BP both arms) Repeat vital signs with any chest pain or equivalent symptoms. Initiate intravenous (IV) and infuse 0.9% sodium chloride at 30mL/hour (left arm preferred) Provide oxygen to keep SpO2 greater than or equal to 90% or with clinical signs of hypoxemia. Give acetylsalicylic acid 160 mg orally now, chewed or swallowed OR acetylsalicylic acid 160 mg orally administered pre-arrival (Time _______).