Giorgio Vasari's Mercury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vasari's Castration of Caelus: Invention and Programme

VASARI’S CASTRATION OF CAELUS: INVENTION AND PROGRAMME GIORGIO VASARI: The “CASTRAZIONE DEL CIELO FATTA DA SATURNO” [1558], in: Ragionamento di Giorgio Vasari Pittore Aretino fatto in Firenze sopra le invenzioni delle storie dipinte nelle stanze nuove nel palazzo ducale Con lo Illustrissimo Don Francesco De’ Medici primo genito del Duca Cosimo duca di Fiorenza, Firenze, Biblioteca della Galleria degli Uffizi (Manoscritto 11) and COSIMO BARTOLI: „CASTRATIONE DEL CIELO“, 1555, in: “Lo Zibaldone di Giorgio Vasari”, Arezzo, Casa Vasari, Archivio vasariano, (Codice 31) edited with an essay by CHARLES DAVIS FONTES 47 [10 February 2010] Zitierfähige URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2010/894/ urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-artdok-8948 1 PREFACE: The Ragionamenti of Giorgio Vasari, describing his paintings in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, the Medici ducal palace, is a leading example of a sixteenth-century publication in which the author describes in extenso his own works, explicating the inventions and, at times, the artistry that lie behind them, as well as documenting the iconographic programme which he has followed. Many of the early surviving letters by Vasari follow a similar intention. Vasari began working in the Palazzo Vecchio in 1555, and he completed the painting of the Salone dei Cinquecento in 1565. Vasari had completed a first draft of the Ragionamenti in 1558, and in 1560 he brought it to Rome, where it was read by Annibale Caro and shown to Michelangelo (“et molti ragionamenti fatte delle cose dell’arte per poter finire quel Dialogo che già Vi lessi, ragionando lui et io insieme”: Vasari to Duke Cosimo, 9 April 1560). -

Coexistence of Mythological and Historical Elements

COEXISTENCE OF MYTHOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ELEMENTS AND NARRATIVES: ART AT THE COURT OF THE MEDICI DUKES 1537-1609 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Greek and Roman examples of coexisting themes ........................................................................ 6 1. Cosimo’s Triumphal Propaganda ..................................................................................................... 7 Franco’s Battle of Montemurlo and the Rape of Ganymede ........................................................ 8 Horatius Cocles Defending the Pons Subicius ................................................................................. 10 The Sacrificial Death of Marcus Curtius ........................................................................................... 13 2. Francesco’s parallel narratives in a personal space .............................................................. 16 The Studiolo ................................................................................................................................................ 16 Marsilli’s Race of Atalanta ..................................................................................................................... 18 Traballesi’s Danae .................................................................................................................................... 21 3. Ferdinando’s mythological dream ............................................................................................... -

Stanley G. Weinbaum's Planetary Stories

FFOORRGGOOTTTTEENN FFUUTTUURREESS BBYY SSTTAANNLLEEYY GG.. WWEEIINNBBAAUUMM FORGOTTEN FUTURES XI: THE PLANETARY SERIES BY STANLEY G. WEINBAUM COVER ILLUSTRATIONS COPYRIGHT © MARCUS L. ROWLAND 2010 This collection of stories is edited to this form to accompany Forgotten Futures XI: Planets of Peril, a role playing game based on the stories. Several other stories by Weinbaum can be downloaded in HTML form from the Forgotten Futures sites. The last story of this sequence, Tidal Moon, could not be included since it was completed posthumously by Helen Weinbaum and remains in European copyright. It can be downloaded from Project Gutenberg Australia. To the best of my knowledge and belief all European copyright in these works of Stanley Weinbaum has now expired. No copyright in these works is claimed by the current editor. While every effort has been made to remove OCR and other errors it is likely that some remain. Some obvious proofreading and editorial errors found in the original books have been corrected. I have not tried to convert American English to British English! Special thanks to Malcolm Farmer for his help with scanning, OCR, proofreading etc. Print formatting: If you print double-sided, for best results print the cover and this page single sided, and all remaining pages double sided. This is a FREE download; please inform me if you are charged any fee to obtain it in any form. Marcus L. Rowland – July 2010 A Martian Odyssey 1 July 1934 Valley of Dreams 16 November 1934 Flight on Titan 30 January 1935 Parasite Planet 43 February 1935 The Lotus Eaters 60 April 1935 The Planet of Doubt 77 October 1935 The Red Peri 94 November 1935 The Mad Moon 123 December 1935 Redemption Cairn 136 March 1936 Tidal Moon December 1938 (not included for copyright reasons) Stanley G. -

Tuccia and Her Sieve: the Nachleben of the Vestal in Art

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË Tuccia and her sieve: The Nachleben of the Vestal in art. Sarah Eycken Presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Supervisor: prof. dr. Barbara Baert Lector: Katlijne Van der Stighelen Academic year 2017-2018 371.201 characters (without spaces) KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË I hereby declare that, in line with the Faculty of Arts’ code of conduct for research integrity, the work submitted here is my own original work and that any additional sources of information have been duly cited. I! Abstract This master dissertation on the Nachleben in art of the Vestal Tuccia and her sieve, tries to chart the motif’s course throughout the history of art, using a transhistorical approach excluding an exhaustive study which lies outside the confines of this paper. Nevertheless, different iconographical types of the representations of Tuccia, as well as of their relative importance, were established. The role of Tuccia in art history and, by ex- tension, literature, is not very substantial, but nonetheless significant. An interdisciplinary perspective is adopted with an emphasis on gender, literature, anthropology and religion. In the Warburgian spirit, the art forms discussed in this dissertation are various, from high art to low art: paintings, prints, emblemata, cas- soni, spalliere, etc. The research starts with a discussion on the role of the Vestal Virgins in the Roman Re- public. The tale of the Vestal Virgin Tuccia and her paradoxically impermeable sieve, which was a symbol of her chastity, has spoken to the imagination of artists throughout the ages. -

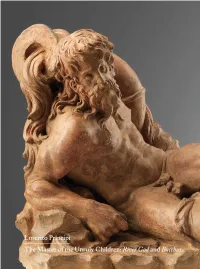

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

Leon Battista Alberti

THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR ITALIAN RENAISSANCE STUDIES VILLA I TATTI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy VOLUME 25 E-mail: [email protected] / Web: http://www.itatti.ita a a Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 AUTUMN 2005 From Joseph Connors: Letter from Florence From Katharine Park: he verve of every new Fellow who he last time I spent a full semester at walked into my office in September, I Tatti was in the spring of 2001. It T This year we have two T the abundant vendemmia, the large was as a Visiting Professor, and my Letters from Florence. number of families and children: all these husband Martin Brody and I spent a Director Joseph Connors was on were good omens. And indeed it has been splendid six months in the Villa Papiniana sabbatical for the second semester a year of extraordinary sparkle. The bonds composing a piano trio (in his case) and during which time Katharine Park, among Fellows were reinforced at the finishing up the research on a book on Zemurray Stone Radcliffe Professor outset by several trips, first to Orvieto, the medieval and Renaissance origins of of the History of Science and of the where we were guided by the great human dissection (in mine). Like so Studies of Women, Gender, and expert on the cathedral, Lucio Riccetti many who have worked at I Tatti, we Sexuality came to Florence from (VIT’91); and another to Milan, where were overwhelmed by the beauty of the Harvard as Acting Director. Matteo Ceriana guided us place, impressed by its through the exhibition on Fra scholarly resources, and Carnevale, which he had helped stimulated by the company to organize along with Keith and conversation. -

Urantia, 606 of Satania by Israel Dix © 2010

1 Urantia, 606 of Satania By Israel Dix © 2010 Numbering the Stars Said Machiventa to Abraham: "Look now up to the heavens and number the stars if you are able; so numerous shall your seed be.”(1020.6) In attempting to do just that, to number the stars, you and I will most certainly be taking a journey over some steep, rocky terrain, number-crunching math, and, out of necessity I’m afraid, plenty of interesting quotes. Lots of them. Because of this I have attempted to keep reference numbers small and out of the way on the trail, so to avoid distraction from the easy flow of this adventure in star searching. Additionally is the added energy boost in knowing that, staying the course, there is at the end of our trek a beautiful picture, a surprisingly organized structure – the Satania System of worlds. So bear with me up this hill we are about to climb. We begin with the problem that set me out on this exploration in the first place: Why does Urantia, a decimal world, end on the peculiar number of six, rather than zero which is a multiple of ten? There must be some explanation for this, and it was a minute hunch that there was an answer that led me first to explore this seemingly unimportant information. The small but nagging question kept returning to mind on occasion, “Ought Urantia to end instead on a zero?” One might get the faint sense that there is an answer to this riddle. But do we have an indication of this, or is it simply a wild chase that dead ends in an attempt to number the stars. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci: Beauty. Politics, Literature and Art in Early Renaissance Florence

! ! ! ! ! ! ! SIMONETTA CATTANEO VESPUCCI: BEAUTY, POLITICS, LITERATURE AND ART IN EARLY RENAISSANCE FLORENCE ! by ! JUDITH RACHEL ALLAN ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT ! My thesis offers the first full exploration of the literature and art associated with the Genoese noblewoman Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci (1453-1476). Simonetta has gone down in legend as a model of Sandro Botticelli, and most scholarly discussions of her significance are principally concerned with either proving or disproving this theory. My point of departure, rather, is the series of vernacular poems that were written about Simonetta just before and shortly after her early death. I use them to tell a new story, that of the transformation of the historical monna Simonetta into a cultural icon, a literary and visual construct who served the political, aesthetic and pecuniary agendas of her poets and artists. -

The Ashgate Research Companion to Giorgio Vasari Vasari and Vincenzo

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 26 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Ashgate Research Companion to Giorgio Vasari David J. Cast Vasari and Vincenzo Borghini Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613017.ch2 Robert Williams Published online on: 28 Dec 2013 How to cite :- Robert Williams. 28 Dec 2013, Vasari and Vincenzo Borghini from: The Ashgate Research Companion to Giorgio Vasari Routledge Accessed on: 26 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613017.ch2 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 2 Vasari and Vincenzo Borghini Robert Williams Vasari’s association with Don Vincenzo (or Vincenzio) Borghini, the Benedictine monk and scholar who was also one of Duke Cosimo de’ Medici’s most trusted advisors and civil servants, stretched from at least the end of the 1540s until the artist’s death in 1574. -

Giorgio Vasari at 500: an Homage

Giorgio Vasari at 500: An Homage Liana De Girolami Cheney iorgio Vasari (1511-74), Tuscan painter, architect, art collector and writer, is best known for his Le Vile de' piu eccellenti architetti, Gpittori e scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (Lives if the Most Excellent Architects, Painters and Sculptors if Italy, from Cimabue to the present time).! This first volume published in 1550 was followed in 1568 by an enlarged edition illustrated with woodcuts of artists' portraits. 2 By virtue of this text, Vasari is known as "the first art historian" (Rud 1 and 11)3 since the time of Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historiae (Natural History, c. 79). It is almost impossible to imagine the history ofItalian art without Vasari, so fundamental is his Lives. It is the first real and autonomous history of art both because of its monumental scope and because of the integration of the individual biographies into a whole. According to his own account, Vasari, as a young man, was an apprentice to Andrea del Sarto, Rosso Fiorentino, and Baccio Bandinelli in Florence. Vasari's career is well documented, the fullest source of information being the autobiography or vita added to the 1568 edition of his Lives (Vasari, Vite, ed. Bettarini and Barocchi 369-413).4 Vasari had an extremely active artistic career, but much of his time was spent as an impresario devising decorations for courtly festivals and similar ephemera. He praised the Medici family for promoting his career from childhood, and much of his work was done for Cosimo I, Duke of Tuscany. -

Cosimo Bartoli and Michelangelo

STUDIES, BIBLIOGRAPHIES, AND REFERENCE PUBLICATIONS ABOUT SOURCES AND DOCUMENTS, 2 STUDIEN, BIBLIOGRAPHIEN UND NACHSCHLAG-PUBLIKATIONEN ZU QUELLENSCHRIFTEN , 2 STUDIES, NO. 2 / STUDIEN, NR. 2 CHARLES DAVIS COSIMO BARTOLI AND MICHELANGELO A Study of the Sources for Michelangelo by Bartoli with excerpts from the RAGIONAMENTI ACCADEMICI DI COSIMO BARTOLI GENTIL’ HUOMO ET ACCADEMICO FIORENTINO, SOPRA ALCUNI LUOGHI DIFFICILI DI DANTE (Venezia: de Franceschi, 1567) and other works by Bartoli FONTES 64 [15. January 2012] Zitierfähige URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2012/1825/ urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-artdok-18257 1 SOURCES AND DOCUMENTS FOR MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI – E-TEXTS, NO. 8 QUELLEN UND DOKUMENTE ZU MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI – E-TEXTE, NR. 8 COSIMO BARTOLI AND MICHELANGELO A Study of the Sources for Michelangelo by Bartoli with excerpts from the Ragionamenti Accademici of Cosimo Bartoli (Venezia: Francesco de’ Franceschi Senese, 1567) and other works by the same author Ragionamenti Accademici di Cosimo Bartoli Gentil’huomo et Accademico Fiorentino, sopra alcuni luoghi difficili di Dante. Con alcune Inventioni & significati, & la Tavola di piu cose notabili, Venezia: Francesco de’ Franceschi Senese, 1567 PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR AFTER A DRAWING BY VASARI. FONTES 64 Bartoli’s Ragionamenti accademici (1567) is presently online and fully accessible („full view“/“vollständige Ansicht“) at GOOGLE BOOKS in a complete digital facsimile of the exemplar at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek and with a partially searchable, but textually