Creating a Future for an Ancient Sustainable City, Yazd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran Discovery Tour - 8 Days Tehran, Shiraz, Yazd, Isfahan, Kashan

Iran Discovery Tour - 8 Days Tehran, Shiraz, Yazd, Isfahan, Kashan Day 1 Arrive in Tehran Welcome to the Land of Persia. We will start our first day after the having our breakfast. Today you will get familiar with our Imperial history. – Saad Abad Palace – Cinema museum (Enjoy your coffee in the beautiful garden of this ancient hunting palace) Day 2 Shiraz Head to the airport for a short flight to Shiraz after having breakfast and checking- out. Shiraz is known as the city of poets, literature and flowers. It is also considered by many Iranians to be the city of gardens due to the many gardens and fruit trees that can be seen in the city. -Eram Garden(UNESCO Site) -Hafez Tomb -Sadi Tomb Day 3 Shiraz Head to the Zand complex including the castle, old colorful bazaar and mosque to get a sense of Shiraz as a capital 250 years ago. We will continue visiting the sites of this famous city. – Karim Khan Zand Castle – Vakil Hamam – Old Bazar – Jameh Mosque – Pink Mosque Day 4 Persepolis / Yazd On the way to Yazd we are going to visit the three most important sites in Iran. It represents the Achaemenid style of architecture. – Persepolis – Pasargad – Necropolis • 7 Mezher Street, Antelias • 60-233 Beirut, Lebanon • +961 4 712037 www.ventnouveau.com • [email protected] Day 5 Yazd You will get familiar with Zoroastrian culture in this ancient city. Because of generations of adaptations to its desert surroundings, Yazd has a unique Persian architecture and it is also called the city of wind towers. -

Oribatid Mites (Acari: Oribatida) of Taft County, Yazd Province of Iran, with New Records

Persian J. Acarol., 2020, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 141–160. http://dx.doi.org/10.22073/pja.v9i2.58955 Journal homepage: http://www.biotaxa.org/pja Article Oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) of Taft county, Yazd province of Iran, with new records Mohammad Ali Akrami* and Alireza Shahedi Department of Plant Protection, School of Agriculture, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran; E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] * Corresponding author ABSTRACT Faunal study of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) in Taft township (Yazd province, central Iran) was conducted for the first time. In total, 63 species belonging to 48 genera and 31 families were collected and identified. Among them, five species Cosmochthonius plumatus Berlese, 1910, Thamnacarus smirnovi Bulanova-Zachvatkina, 1978, Acrotritia simile Mahunka, 1982, Belba bulanovae Subías, 2016, and Bipassalozetes lineolatus (Sitnikova, 1975) are newly recorded for mite fauna of Iran, and 13 families, 25 genera and 36 species are reported for the first time from the Yazd province. KEY WORDS: Arthropoda; central Iran; Cryptostigmata; fauna; Sarcoptiformes. PAPER INFO.: Received: 29 December 2019, Accepted: 12 February 2020, Published: 15 April 2020 INTRODUCTION Yazd province (29° 48' to 33° 30' N and 52° 45' to 56°30' E) is situated in the Central Plateau of Iran (Fig. 1), a region at an oasis where the Dasht-e Kavir and the Dasht-e Lut deserts meet, covering about 74,493 km2 (4.5% of total area of Iran). Most of the area includes desert plain regions (the desert areas cover about 38% of Yazd province, and the areas include different desert geomorphologic faces) surrounded with mountains, running from a northwestern to a southeastern direction. -

TJG-Mar 17-Yazd

Tuesday, March 17, 2015 Jakarta Globe Life & Style 23 In Yazd, an Eternal Flame Burns Bright Wahyuni Kamah visits the Persian desert city at the heart of an ancient and intriguing religion arrived at the main bus terminal in Yazd, the capital of the eponymous province in Iran, at night, and immediately I had the impression of a city that was wide sprawling. There were no high-rise buildings visible, Iand the city stretched out flat and low. I couldn’t wait until day broke to see and explore the city, located about 630 kilometers southeast of Tehran. Yazd was the center of Zoroastrianism when the Sasanian Empire (224 to 651 C.E.) ruled Persia, and takes its name from Yazdegerd I, one of the rulers of the dynasty, who reigned from 399 to 421. Zoroastrianism is an ancient mono- theistic religion founded more than 3,500 years ago by Zoroaster (or Zarathustra), and was the predominant faith during the Sasanian era. I wanted to know more about it, so the next morning I hired a taxi to take me to the Towers of Silence, among the last remnants of that time. Located in the middle of the country and surrounded by deserts — Dasht-e- Kavir to the north and Dasht-e-Lut to the The Towers of Silence, top, in the desert outside Yazd served as funerary structures for the south — Yazd is the driest city in Iran. As ancient Zoroastrian faith, which is still practiced in Yazd. JG Photos/Wahyuni Kamah we drove to the site, I could see how the desert climate had compelled the inhab- Fire, and water, are agents of purity in the world today — eight in India and only itants of this city of just over a million to a Zoroastrianism, and not objects of wor- the one in Iran. -

Takhté Soleymān

Historical Site of Mirhadi Hoseini http://m-hosseini.ir ……………………………………………………………………………………… Takhté Soleymân Azar Goshnasp Fire-Temple Complex By Professor Dietrich Huff Takht-e Soleymân is an outstanding archeological site with substantial Sasanian and Il-khanid ruins in Azarbaijan province, between Bijâr and Šâhin-dež, about 30 km north-northeast of Takâb, with about 2, 200 m altitude, surrounded by mountain chains of more than 3000 m altitude. The place was obviously chosen for its natural peculiarity; an outcrop of limestone, about 60 m above the valley, built up by the sediments of the overflowing calcinating water of a thermal spring-lake (21° C) with about 80 m diameter and more than 60 m depth on the top of the hill (Damm). The place is mentioned in most of the medieval Oriental chronicles (e.g., Ebn Khordâdbeh, pp. 19, 119 ff.; Tabari, p. 866; Nöldeke, p. 100, n. 1; Bel'ami, p. 942, tr., II, p. 292; Ebn al-Faqih, pp. 246, 286; Mas'udi, ed. Pellat, sec. 1400, tr., IV, pp. 74 f; idem, Tanbih, p. 95; Abu Dolaf, pp. 31 ff.; Ferdowsi, pp. 111 ff.; Yâqut, Beirut, III, pp. 383-84, tr., pp. 367 ff; Qazvini, II, pp. 267; Hamd-Allâh Mostawfi, p. 64, tr., p. 69, who attributes its foundation to the Kayanid Kay Khosrow) and was visited and described repeatedly by western travelers and scholars since the 19th century (e.g., Ker Porter, pp. 557 ff.; Monteith, pp. 7 ff.; Rawlinson, pp. 46 ff.; Houtum Schindler, pp. 327 f.; Jackson, 1906, pp. 124 ff.). It was erroneously taken for a second Ecbatana (q.v.) by Henry Rawlinson, and defective Byzantine sources caused it to be confused with the great Atropatenian city of Ganzak (q.v.) and other places (Minorsky). -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Epidemiological Study of an Outbreak of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Five Endemic Foci, Yazd Province, Iran March 2015–March 2016

Journal of Community Health Research 2017; 6(2): 77-84. JCHR Epidemiological Study of an Outbreak of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Five Endemic Foci, Yazd Province, Iran March 2015–March 2016. Mohammad Hassan Lotfi1, Soheila Noori2*, AliAkbar Taj Firouze3, Hossein Fallahzadeh4, Jamshid Ayatollahi5 1. Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Health Faculty, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. 2. Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Health Faculty, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. 3. Deputy for Health Affairs, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. 4. Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Health Faculty, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. 5. Infectious and Tropical Diseases Research Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Original Introduction: Iran is majorly affected by the Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL). Despite continued efforts toward control, the incidence of CL has increased in Received: 31 Nov 2016 the many areas of Iran. The counties of Ardakan, Khatam, Bafgh, Abarkuh, and Accepted: 18 Mar 2017 Yazd are endemic places for CL. An outbreak occurred in the Yazd province them between March 2015 and March 2016.The aim of this paper was to identify the epidemiological and clinical aspects of leishmaniasis in patients that were reported from these five endemic foci during the outbreak. Methods: This descriptive study was conducted on 150 patients suffering from CL who were referred to the provincial health center during the period of outbreak. Clinical and demographic information of the patients were registered Corresponding Author: and analyzed by the SPSS 23 software. Result: From the 150 cases considered, 121 subjects (80.2%) lived in urban areas. -

Geotourism Attractions in the Bare Nature of Yazd Province

ADVANCES IN BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH Geotourism Attractions in the Bare Nature of Yazd Province KAMAL OMIDVAR1, YOUNES KHOSRAVI2 1Department of Geography 2Department of Geography 1 Yazd University 2 Yazd University 1Address: Faculty of Human Science, Yazd University, Yazd Iran 2Address: Faculty of Human Science, Yazd University, Yazd Iran 1E-mail: [email protected] 2E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Climatic conditions governing over Yazd province have caused a situation in which the most areas covered by bare and barren lands. Relief in this province is rooted in the ancient geology history of Iran and the world. From the most ancient structures of the geology in the world (Precambrian) to the newest ones (Holocene) are seen at a distance which is less than 100 km in this province. We can rarely see very various ecotourism attractions such as deserts, salt playas, sand dunes, Qantas, glacial circuses, spring, karstic caves and kalouts in the other areas of the world in a small distance away from each other. Therefore this province can have special status in ecotourism industry because of its attractions and developing this industry will result in socio-economic advancement and an increase in the employment rate in Yazd province.This research attempts to consider ecotourism attractions briefly in Yazd province and introduce available potential abilities in this field. Key-Words: Ecotourism, Sand Dune, Playa, Qanat, Desert, Glacial Circus, Kalout, Yazd Province. 1 Introduction conducted studies on the shapes and relief of the Climatic variety not only in current age, but also in earth in Yazd province confirm the presence of various climatic periods has been very diverse in fossils from Precambrian period (approximate age is Yazd province area. -

The Potential and Characteristics of Solar Energy in Yazd Province, Iran

Iranica Journal of Energy & Environment 5 (2): 173-183, 2014 ISSN 2079-2115 IJEE an Official Peer Reviewed Journal of Babol Noshirvani University of Technology DOI: 10.5829/idosi.ijee.2014.05.02.09 BUT The Potential and Characteristics of Solar Energy in Yazd Province, Iran 1, 2H. Khorasanizadeh, 1, 2K. Mohammadi and 1, 2A. Aghaei 1Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, University of Kashan, Kashan, Iran, Post Code: 87317-51167 2Energy Research Institute, University of Kashan, Kashan, Iran Received: March 28, 2014; Accepted in Revised Form: June 11, 2014 Abstract: In this study, utilizing the obtained data from four distributed locations known as Abarkuh, Behabad, Halvan and Yazd, the solar energy potential and its characteristics in Yazd province of Iran have been evaluated. For the data, daily horizontal global radiation (HGR) and clearness index also their monthly, seasonal and yearly averaged values have been obtained. The results indicate that the four locations enjoy from 300, 294, 289 and 311 sunny and very sunny days; their yearly averaged daily clearness indexes are 0. 66, 0. 66, 0. 64 and 0. 67 and their yearly averaged daily global radiations are 20. 74, 20. 78, 19. 52 and 20. 60 MJ/m2 , respectively. In overall, Yazd province enjoys from sunshine hours in almost 76% of the whole day times and its annually averaged daily HGR and clearness index are 20. 41 MJ/m2 and 0. 66, respectively. Making comparison between the four nominated locations of Yazd province and 7 other selected cities around the globe, but at the same latitude, except Arizona, revealed that, their monthly mean daily global radiation and clearness index are higher than those of other six selected cities. -

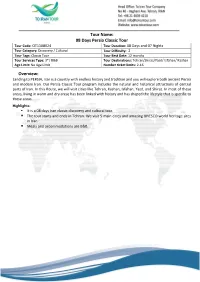

Tour Name: 08 Days Persia Classic Tour Overview

Tour Name: 08 Days Persia Classic Tour Tour Code: OT1108024 Tour Duration: 08 Days and 07 Nights Tour Category: Discovery / Cultural Tour Difficulty: 2 Tour Tags: Classic Tour Tour Best Date: 12 months Tour Services Type: 3*/ B&B Tour Destinations: Tehran/Shiraz/Yazd/ Isfahan/ Kashan Age Limit: No Age Limit Number ticket limits: 2-16 Overview: Landing to PERSIA, Iran is a country with endless history and tradition and you will explore both ancient Persia and modern Iran. Our Persia Classic Tour program includes the natural and historical attractions of central parts of Iran. In this Route, we will visit cities like Tehran, Kashan, Isfahan, Yazd, and Shiraz. In most of these areas, living in warm and dry areas has been linked with history and has shaped the lifestyle that is specific to these areas. Highlights: ▪ It is a 08 days Iran classic discovery and cultural tour. ▪ The tour starts and ends in Tehran. We visit 5 main cities and amazing UNESCO world heritage sites in Iran. ▪ Meals and accommodations are B&B. Tour Itinerary: Landing to PERSIA Welcome to Iran. To be met by your tour guide at the airport (IKA airport), you will be transferred to your hotel. We will visit the lavish Golestan Palace*, this fabulous walled complex is centered on a landscaped garden with tranquil pools. Time permitting; we can walk around Grand old Bazaar of Tehran, few steps far from Golestan Palace. Continue along the Bazaar route. Then at night, we take a flight to Shiraz. O/N Shiraz Note: The priority in sightseeing may be changed due to the time of your arrival, preference of your guide and also official and unofficial holidays of some museums. -

Pdf 799.44 K

Available online at www.jrors.ir Journal Of Radar and Optic Remote Sensing JRORS 2 (2018) 79–93 Investigating the role of duality in geomorphology using radar data in Bahadoran plain of Yazd Hamed Piri a*, Abolqasem Amir Ahmadi b , Hamed Adabc a Member of young researcher club, Islamic Azad university, Safadasht Branch, Tehran,Iran b Associate Professor of Faculty of Geography, Hakim University of Sabzevar c Assistant Professor of Faculty of Geography, Hakim Sabzevari University Received 23 May 2018; revised 22 September 2018; accepted 22 October 2018 Abstract Many varied attitudes exist about how the changes occur in the land-surface from the time of William Davis’s research to the latest researchers in the history of geomorphologic philosophy and many different terms are used by scientists in order to observe their ideas related to geomorphic phenomena. The phenomenon of duality has been seen less in the geomorphology field. There exist some contradictory phenomena in nature, but further investigation can show their correlation clearly. Durability can be considered as a better dynamic entropy. In this research, radar interferometry technique has been used in Yazd-Bahadoran area and the amount of subsidence and uplifting has been investigated Through field and library studies and the results have been compared with the other researchers' studies, which is a new concept in the literature of geomorphology under geo-duality. The study results indicate that the main reason for the subsidence was not to cut down the level of groundwater, and in this regard the tectonic movements play a significant role. Also, the study shows a significant relationship between subsidence in the Bahadoran plain and the collapse in adjacent heights in terms of duality or dichotomy. -

Meybod-Yazd- Shiraz -Esfahan -Abyaneh -Kashan-Tehran

Type &name of the tour: Classic Itinerary, visiting cultural & historical highlights of Nae'in –Meybod-Yazd- Shiraz -Esfahan -Abyaneh -Kashan-Tehran :Itinerary 1 st Day – Arrival-Tehran Arrival in Imam Khomeini international airport, after greeting, transfer to the hotel and rest, visiting some highlights of Tehran ,the Capital of Iran ,including Ancient National Museum and Abgineh (Glass) Museum (Ancient National & Abgineh Museums are closed on Mondays & holly memorial), Golestan Palace (closed (on holly memorial ceremonies) , O/N Tehran (Hotel –B 2 nd Day-Tehran - Nae'in-Meybod-Yazd Driving to Yazd, visiting Meybod & Nae’in Historical highlights en route; including Pirniya Museum and Congressional Mosque, in Nae’in , and caravansary, Narin Ghaleh (fortress), traditional refrigerator ,Chaparkhane (old post center) ,Pigeon Tower and (Ceramic shops of Meybod, O/N Yazd (Hotel-B 3 rd Day - Yazd Full day city tour of Yazd ,the old city with interesting desert architecture, visiting the highlights of Yazd including Amir Chakhmagh Complex, Fahaadan old neighborhood ,Zeyaeyeh School (Aleksandra Prison), Water Museum, Congregational Mosque, Zoroastrian old Fire Temple ,and the tallest Wind Tower in (Dolat Abaad Garden , O/N Yazd (Hotel-B ُ th Day - Yazd - Persepolis-Pasargadae 4 Driving to Shiraz, visiting the most important historical sites of Iranian civilization, dating back to 2500 years ago , including Persepolis (Thakht -e Jamshid ), Pasargadae (Cyrus, the Great tomb) and Naghsh-e- Rostam and Naghsh-e Rajab, en route, O/N (Takht-E-Jamshid -

Life Science Journal 2013;10(7S) 252

Life Science Journal 2013;10(7s) http://www.lifesciencesite.com Acceptability for injury assessment of groundwater resources in plain of Ardakan-Yazd using Drastic Model And GIS 1.S.A.Mirhosseini, 2.H. Zarei Mahmoodabady, 3.Mohsen Bemani 1.Department of Environment, MaybodBranch, Islamic Azad University, Maybod, Iran (Corresponding author). Tel: 00989132552059 E-mail: [email protected] 2.Department of Environment, Maybod Branch, Islamic Azad University, Maybod, Iran 3.M.Scgraduated of Groundwater Hydrology, University of Sistan and Baluchestan, Zahedan, Iran Abstract: Yazd-Ardakan plain was placed at Yazd province center and regarding its structure is a part of Iran central plateau, according to the weather conditions, there is not any kind of permanent river in the region and also other regions of province are dependent to the underground waters and due to the development of industries and importance of aforementioned water resource in the supply of required water of industries agriculture and drinking water in this study using the drastic model, aquifer acceptability for injury of Yazd–Ardakan was compared to the pollution. Since the removal of pollution from underground aquifers is a very expensive affaire and somewhat is impossible, preventing from their pollution is a most important work in order to protect the water resources. Main goal of doing this work is to evaluate the Yazd-Ardakan aquifer acceptability for injury in presence of pollution. In this research after classification and weighting for each one of the effective parameters, the drastic index is calculated per region and according to it the various degrees of vulnerability is identified and acceptability for injury plan is drawn based on the drastic method.